ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

To unveil the physiological relevance of magnesium and its transport pathways in Neurospora crassa, the vegetative, asexual, and sexual phases of development were investigated. Notably, a regular rate of hyphal growth extension was observed in media without magnesium supplementation. Further, conidia and perithecia formation was completely abolished under the same conditions. By estimating the levels of mycelial cations, magnesium was identified as the 3rd most abundant ion and its transport was found to be mediated by four putative CorA magnesium transporters: Tmg-1, Tmg-2, Tmg-3, and Tmg-4. Among these, the Tmg-4 transporter encoded by the NCU07816.5 (tmg-4) gene possesses a GQN motif instead of the universally conserved GMN motif of CorA magnesium transporters. Phenotypic analysis of the knockout mutant strain, Δtmg-4, revealed stunted vegetative growth, acquired partial cobalt resistance, and reduced levels of mycelial magnesium compared to that of the wild type strain. Further, tmg-4 gene expression remained unchanged during vegetative development but was upregulated by three-fold in the sexual cycle. Collectively, these results validate tmg-4 and its encoded protein as functional novel variant in the CorA superfamily magnesium transporters of fungi.

Tmg-4, GQN, STMg, GMN, CorA Superfamily, Neurospora crassa, Sexual Cycle

The mineral, magnesium, is vital to the structural integrity of cell organelles, macromolecules, and hundreds of enzymes involved in diverse biochemical reactions.1-4 The levels of magnesium must be finely regulated in all cellular forms, and magnesium transporters play an important role in this process. An array of Mg2+ transporters has been discovered and characterized in both prokaryotes (CorA, MgtE, and MgtA/B) and eukaryotes (Mrs2, ALR1 and 2, MNR2, LPE10, SLC41, and the MGT family).5 The crystal structure of TmCorA from Thermotoga maritima was previously determined. TmCorA has a pentameric cone with two transmembrane helices. The GMN motif of TmCorA is universally conserved and present in the first transmembrane domain.6,7 To maintain pentameric integrity and magnesium transport, every amino acid in the GMN motif is extremely important.8,9 Studies using baker’s yeast revealed the presence of a CorA superfamily magnesium transporter with a GMN motif. These transporters are subgrouped as ALR, MNR, and MRS2, which are localized to the plasma membrane, vacuoles, and mitochondrial membrane, respectively.10-13 These dissimilar transporter proteins of the CorA super family mediate the assimilation of magnesium from the environment to the cytoplasm and its distribution to the vacuoles and mitochondria, respectively. Besides magnesium transport in eukaryotes, CorA transporters are necessary for ascospore development, pathogenicity, regulation of virulence factor expression, and melanin synthesis in fungi.14-16 Root endophytic fungus P. indica Mg transporter (PiMgT1) is involved in the improvement of magnesium nutrition for host plants.17 This family of magnesium transporters is also necessary in pollen development, and salt and other abiotic stresses in plants.18-20

Our group recently discovered the CorA magnesium transporter protein, Tmg-4 (NCU07816.5), which contains a GQN motif, from Neurospora crassa. The Tmg-4 homolog proteins with the GQN motif and CorA domain are mainly present in the Sordariomycetes class of fungi and are named STMg.21 The present study focused on magnesium and the role of the Tmg-4 transporter protein in various phases of N. crassa. Our findings confirm that Tmg-4 bearing the GQN motif is a novel variant of the CorA superfamily magnesium transporter involved in intracellular magnesium accumulation. Overall, this study suggests that Tmg-4 with the GQN motif is necessary for the sexual phase in the heterothallic fungi, N. crassa.

Strains, media, and culture conditions

The N. crassa strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The strains were cultured in basal medium (BM) for vegetative growth and synthetic crossing medium (SCM) for crossing.22,23 The conidispore suspension of the strains (100 µl of 1.0 O.D. at 470 nm) was used to inoculate all cultures; the strains were grown in liquid or solid medium (supplemented with 1.5% agar).

Phenotypic characterization of wild type and the knockout mutant

The gene loci, NCU07816.5, named tmg-4 and the corresponding gene knockout strain of N. crassa (∆tmg-4) were obtained from the FGSC (Fungal Genetic Stock Centre) for phenotypic characterization. The conidiospore suspensions of the wild type and ∆tmg-4,24 were inoculated into 10 ml basal medium and incubated at 30°C for three days under stationary conditions for vegetative growth. To estimate mycelial growth, the wild type and ∆tmg-4 were inoculated in liquid basal media containing magnesium concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 2.0 mM. To determine the sensitivity of the wild type and knockout toward CoCl2 and NiCl2, conidiospores of the wild type and ∆tmg-4 were inoculated in liquid basal media supplemented with 0.2 mM MgSO4 and the above cations in individual experiments. The mycelia from liquid cultures were harvested using strainers and washed thrice with deionized water. Filter papers were used to remove excess moisture from mycelia and their dry weights were recorded after drying for 3 h at 80°C or overnight at 60°C. The N. crassa strains were grown on solid basal media with or without MgSO4 in race tubes to measure the rate of hyphal growth extension.25

Conidia and perithecia formation

To evaluate the requirement of magnesium for the proper performance of the asexual and sexual cycles, the N. crassa strains were analyzed by growing on solid basal media (2% Sorbose) or synthetic crossing media with (2.0 mM) or without MgSO4, and with hexamine cobalt (III) chloride (HCC) (150 µM), a competitive inhibitor of CorA magnesium transport.26 For the asexual cycle, wild type N. crassa conidia were inoculated and cultured for 7 days at 30°C. The petri plates were photographed at different time intervals to record growth and development. For the sexual cycle, opposite mating types of wild type N. crassa (mat A, mat a) conidia were implanted on synthetic crossing media on opposites edges of the petri plates. These cultures were maintained under light at 30°C for 9 days and the plates were subsequently photographed.

Element analysis

The N. crassa strains, wild type and knockout ∆tmg-4, were grown in the basal media supplemented with various concentrations of MgSO4 for 3 days at 30°C. The mycelia were then harvested, washed, and dried at 60°C overnight. The respective weights of the mycelia were then recorded. The dried mycelia were subjected to acid digestion in a closed microwave apparatus, and element analysis was performed using Agilent 7700x ICP-MS (Inductively coupled plasma-Mass spectrometry).

RNA isolation

For RNA isolation, the conidia of N. crassa were inoculated, as described previously.27,28 For vegetative growth, conidia (~1 x 107 cells/ml) were inoculated into a 50-ml conical flask containing 10 ml of basal media and incubated at 30°C in stationary mode for 3 days. The effect of magnesium deficiency on tmg-4 gene expression was assessed by harvesting pre-grown mycelia and transferring these mycelia to fresh basal media containing EDTA or HCC. The culture was incubated for 3 h at 30°C under stationary conditions. The wild type N. crassa Mat “A” (#2489) was grown on a petri dish containing synthetic crossing media covered with sterile cellophane for five days, fertilized with heavy conidia of mat “a” (# 4200), and further incubated for three days. The mycelial mats (30 to 50 mg) of the vegetative cultures, unfertilized and fertilized mycelia, and perithecia were collected via scraping from crossing cultures and snap frozen with liquid nitrogen. To isolate total RNA, frozen mycelia were grounded into powder using a chilled mortar and pestle with 0.5 mm acid-washed glass beads. The remaining procedure was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma Plant/Fungi RNA Purification Kit). The integrity of RNA was verified on a 2% agarose gel, and quantification was performed spectrophotometrically.

cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR

Reverse transcription of target mRNA in the total RNA was performed using oligo(dT)18 primers and Thermo Scientific Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer 3 software was used to design the primers used in this study.29 Real-time PCR was performed on an ABI 7500 FAST (Applied biosystems) master cycler using Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (2X). The 2-∆∆Ct method was used for analysis.30 gpd-1 and beta-tubulin were used as internal controls. All qRT-PCR results were expressed relative to that of gpd-1. The oligonucleotides used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table (1):

Strains and Oligonucleotides used

Neurospora crassa Strains |

Genotype/Comment |

Source/cloning site |

|---|---|---|

Wild-type |

74-OR23-1a (#4200)mat a |

FGSC |

Wild-type |

74-OR23-1A(# 2489) mat A |

FGSC |

∆tmg-4 |

(#11968) mat a |

FGSC |

∆tmg-4 |

(#11969) mat A |

FGSC |

Oligonucleotide |

||

Name |

Sequence |

|

Rtmg4-F |

5’CACGATTGCCTTGCGACATA3’ |

|

Rtmg4-R |

5’AGACCATTGACGCTGATCCA3’ |

|

Rt gpd1-F |

5’CATCGTCGAGGGTCTCATGA3’ |

|

Rt gpd1-R |

5’GTGCTGCTGGGAATGATGTT3’ |

|

tmg4-F |

5’GAATTCATGGGATCCAGGTCGCCC3’ |

EcoR1 |

tmg4-R |

5’AAGCTTCTACACCTGCTTCTTTCC3’ |

HindIII |

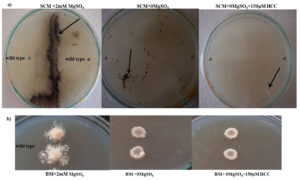

Magnesium is required for the asexual and sexual phases of N. crassa

The N. crassa wild type strain abundantly formed asexual conidia and perithecia in media containing normal levels of magnesium (2 mM) (Figure 1). However, under magnesium depleted conditions, asexual conidia were not produced, and approximately 50-fold less perithecia were formed in the sexual cycle, highlighting the importance of magnesium in the life cycle of N. crassa. Upon media supplementation with HCC (CorA specific inhibitor), the number of perithecia was reduced to a single digit in the petri dish, suggesting that magnesium uptake through the CorA transporter aids in the maintenance of intracellular Mg+2 in N. crassa. Thus, a minimum concentration of magnesium transported through the CorA transporter is critical for the development phases of N. crassa.

Magnesium is the 3rd most abundant cation in the mycelia of N. crassa

Magnesium availability plays a significant role in the asexual and sexual phases. Therefore, we estimated the levels of Mg2+, other cations, macro elements, and trace elements in the mycelia using ICP-MS to determine their cellular levels. Based on the results, magnesium and calcium compete for 3rd position among the tested metals, including K, Na, Mg, Ca, Fe, Zn, Mn, Cu, Ni, and Co (Table 2). The sexual and asexual phases of N. crassa could be dependent on reported levels of magnesium in the mycelium (Figure 1).

Table (2):

Metal ion composition. N.crassa wild type strain grown in Basal media with 2mM of MgSO4 and subjected to acid digestion for major metal ion analysis by ICP-MS

Metal Name |

Metal content in ppb/mg mycelia |

|---|---|

K |

12409.13 ±1005 |

Na |

4092.35 ±100 |

Mg |

1007.35 ±55 |

Ca |

1001.00 ±60 |

Fe |

482.42±20 |

Zn |

93.29±10 |

Mn |

25.99±6 |

Cu |

16.43±2 |

Ni |

5.02±1 |

Co |

0.33±0.1 |

Figure 1. Perithecia and conidia formation. a) For perithecia formation, N.crassa opposite mating types (“A” and “a”) were placed on SCM supplemented with and without MgSO4, HCC and plates were photographed after 9 days incubation at 30°C (Arrows pointed towards perithecia) b) For conidia formation wild type strain (#4200) was grown on Solid BM with and without MgSO4, HCC and photographed after 7 days incubation at 30°C

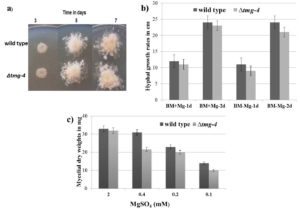

Phenotypic characterization of the ∆tmg-4 knockout mutant and wild type strains

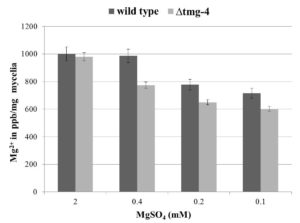

During vegetative growth on solid media for 7 days, no significant difference was found between ∆tmg-4 and wild type N. crassa (Figure 2a). The difference in hyphal growth extension between ∆tmg-4 and the wild type was marginal when grown on solid basal media with and without MgSO4 supplementation (Figure 2b). Further, to determine the growth difference between wild type and ∆tmg-4, the strains were grown in liquid basal media supplemented with 2.0, 0.4, 0.2, and 0.1 mM MgSO4. When magnesium concentration was decreased to 5-fold, ∆tmg-4 exhibited a 20% reduction in growth compared to the wild type. Further, a 20-fold decrease in the magnesium concentration affected the growth of ∆tmg-4 by approximately 68% and wild type strain by 43% (Figure 2c). The cellular levels of magnesium in the wild type and ∆tmg-4 strains of N. crassa were estimated under various concentrations of magnesium in the media. Under 0.4 mM to 0.1 mM MgSO4, ∆tmg-4 exhibited reduced levels of magnesium compared to the wild type strain (Figure 3). However, cellular magnesium levels significantly decreased in ∆tmg-4 compared to that of the wild type strain under 0.4 mM MgSO4. The ∆tmg-4 knockout strain showed less hyphal growth extension, reduced dry weights and cellular magnesium levels, suggesting that tmg-4 is involved in magnesium transport.

Figure 2. Phenotypic characterization of N.crassa strains a) 5ul of 1 O.D conidiospores suspension of wild type and ∆tmg-4 were placed on basal media and incubated at 30°C. b) N.crassa strains were inoculated on solid BM prepared (with and without MgSO4) and in race tubes and hyphal growth extension rates were measured at 1 day and 2 days. c) crassa strains grown in liquid BM containing various concentration of MgSO4 for 3 days and mycelial mats were harvested, dried and weights were recorded

Figure 3. Graphical representation of mycelial magnesium levels in wild type and ∆tmg-4 strains. N. crassa strains grown in BM containing various concentration of MgSO4 at 30°C for 3 days. The dried mycelia were subjected to the acid digestion and elemental analysis was carried out by ICP-MS

∆tmg-4 strain acquires resistance to cobalt

When the cobalt concentration increased from 50 µM to 100 µM in the media, the growth of ∆tmg-4 was not affected whereas the wild type strain suffered growth loss of approximately 15% (Figure 4a). Thus, the acquired resistance of ∆tmg-4 towards cobalt suggests that the Tmg-4 protein transports cobalt when the media concentration of magnesium is 10-fold less. When the toxic effects of nickel were examined, this metal did not induce a growth difference between the wild type and ∆tmg-4 (Figure 4b), indicating sensitivity to nickel by both strains, and highlighting that Tmg-4 may not aid in nickel transport.

Figure 4. Mycelial growth in the presence of Cobalt and Nickel. Conidiospores of wildtype, Δtmg-4, strains were inoculated into liquid BM containing various levels of Cocl2 and NiCl2. After 3 days of stationary growth mycelia were harvested and dried at 60°C for overnight and weights were recorded

tmg-4 gene expression is marginally upregulated in the sexual cycle

The gene expression of tmg-4 was studied in wild type grown in the presence of 100 µM, 200 µM, and 400 µM MgSO4 for 3 days. The transcript levels of the tmg-4 gene remained the same, irrespective of the concentration of magnesium in the media, indicating no influence of Mg2+ on the gene expression (Table 3). The gene expression of tmg-4 in basal media (BM) without magnesium, BM with 100 µM EDTA chelator of the divalent ion, and 300 µM HCC for 3 h was also checked. In all cases, the transcript levels of tmg-4 were similar to those in media supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, confirming that the external supply of divalent metal chelator or competitive inhibitor of magnesium could not induce a change in gene expression (Table 3). Interestingly, tmg-4 gene expression was upregulated by 3-fold in the culture undergoing sexual development compared with the culture before crossing. In contrast, tmg-4 expression in perithecia exhibited the same trend as that observed under vegetative conditions (Table 3). Thus, the tmg-4 gene may be required for the sexual development of N. crassa.

Table (3):

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR: The tmg-4 gene expression analyzed by qRT-PCR in various conditions. In 1) and 2) mycelia grown in Basal media containing 2mM MgSO4 was taken as control to analyze the tmg-4 expression in indicated Conditions. In 3) unfertile mycelia, before crossing was used as control. The gpd-1 transcript was used for normalization

1) Condition: Vegetative growth (3 days) |

Fold change |

Basal Media(BM) with 400µM MgSO4 |

1.201±0.15 |

BM 200µM MgSO4 |

1.143±0.10 |

BM 100µM MgSO4 |

1.162±0.13 |

2) Condition: Vegetative growth (3hours) |

|

BM without MgSO4 |

1.301±0.11 |

BM with 100µM EDTA |

1.173±0.14 |

BM with 300µM HCC |

1.152±0.12 |

3) Condition: Sexual cycle |

|

After crossing (3 days) |

3.203±0.16 |

Perithecia (8 days) |

1.546±0.13 |

Importance of magnesium and its transporters in N. crassa

To understand the importance of magnesium in N. crassa, the asexual and sexual developmental phases were investigated. Herein, the asexual and sexual phases of N. crassa were successful, with the production of abundant conidia and perithecia in the presence of magnesium (2 mM). The lack of magnesium supplementation and chemical inhibition of Mg2+ transport by the CorA inhibitor, HCC, completely abolished the formation of conidia and perithecia. This remarkable effect suggests that CorA-mediated magnesium transport is the only means of transporting magnesium from media to N. crassa. We proceeded to examine whether a decrease in Mg2+ concentration affects the metal ion composition. Element analysis revealed that magnesium is the 3rd most abundant metal after sodium and potassium. In addition, the level of cellular magnesium reduced to 30% with a 10-fold decrease in magnesium concentration in basal media. Therefore, the percent of magnesium in the media might play a significant role in the physiology and development of the model fungal organism, N. crassa.

Tmg-4 is a CorA magnesium transporter with a GQN motif and a novel variant from Sordariomycetes

Owing to the importance of magnesium in the lifecycle of N. crassa, we opted to analyze the genome to determine the genes responsible for magnesium uptake from milieu to macromolecules. Preliminary studies revealed that the four gene loci belonging to the CorA superfamily are responsible for magnesium uptake.5 Three of the four (tmg-1, tmg-2, and tmg-3) genes encoded proteins comprising 2TMS and the GMN motif, which are universally conserved and hallmarks of the CorA superfamily.8,9 In silico analysis of four clades and structural superposition of the crystal structure of CorA (GMN motif) with a homology model of Tmg-4 (GQN motif) confirmed GQN as a novel motif and suggests its potential candidate for magnesium transport in N. crassa.21 Similar to the Tmg-4 with GQN observation in N. crassa, the glycine residue on the GMN motif of CorA transporters was substituted in few plant species, which exhibited functional activities. For example, Arabidopsis AtMRS2-11 encodes an Mg2+ channel that mediates fast Mg2+ transport. The glycine residue in the GMN motif of AtMRS2-11 is essential for the transport of magnesium at low physiological Mg2+ concentrations. However, replacing the glycine of GMN with alanine, serine, valine, or tryptophan revealed that mutants can transport the magnesium at higher concentrations.31 A natural replacement for glycine was found in a CorA/MRS2-like protein of Brachypodium distachyon (BdMGT5-1), which forms a WMN motif.32 Wild-type maize ZmMGT6 containing the AMN motif but not the GMN motif retains its transport activity and complements yeast Mg2+-deficient strains.33 A total of 24 MGT genes were identified in wheat, and only TaMGT1A, TaMGT1B, and TaMGT1D had GMN mutations to AMN.20

To verify the in silico results that the tmg-4 encoded protein is a magnesium transporter or any other divalent transporter and validate the real nature of the gene, the tmg-4 knockout strain was used for functional analysis. In this study, a growth defect was observed in ∆tmg-4 relative to the wild type under Mg2+ limiting conditions (0.4 mM MgSO4), whereas marginal differences in hyphal growth rates were observed between the wild type and ∆tmg-4 strains. In addition, a decrease in the level of magnesium in media reveals that both strains suffered growth loss. The severity of the growth defect was further intensified by double knockout (∆tmg-1 and ∆tmg-4), resulting in complete loss at 16 µM MgSO4 relative to that of the wild type strain, which retained 30% growth (data not shown). This result indicates that the loss of one gene may affect the growth of the knockout strain up to 20 to 30% under magnesium-depleted conditions. Thus, our results supporting the phenotypic defects suggest that these four genes might play a significant role at different levels of magnesium transport, similar to other fungal systems. Consequently, mycelial growth in the presence of cobalt and nickel revealed that ∆tmg-4 is partially resistant to cobalt compared with the wild type strain; however, nickel did not lead to differences. We assume that cobalt toxicity in the wild type is due to the presence of four transporters, which may accumulate more cobalt than the ∆tmg-4 with three transporters. Elemental analysis also revealed that ∆tmg-4 accumulated 19% less cellular magnesium than the wild type. These results suggest that lack of the tmg-4 gene in N. crassa affected its growth, reduced magnesium accumulation, and led to its acquisition of partial resistance to cobalt chloride. This result highlights the tmg-4 gene encoded protein as a magnesium transporter that may be decorated in the plasma membrane of the cell. Although pBLAST analysis of the Tmg-4 revealed the homologs to the CorA and ZntB34 (efflux or influx of Zinc and Cadmium) family, our analysis proves that Tmg-4 of the STMg group is a magnesium transporter that co-transports cobalt, and is not a zinc transporter.

Functional role of Tmg -4 with the GQN motif in N. crassa

To gain insights into the functional role of Tmg-4, we evaluated the expression of the tmg-4 gene in the wild type. The expression of the tmg-4 gene was unaltered in the wild type vegetative culture in response to various concentrations of magnesium, EDTA, or HCC. In contrast, a 3-fold upregulation of gene expression was observed in the sexual cycle in fertilized mycelia relative to the unfertilized or before crossing. The tmg-4 expression under vegetative conditions was found to be similar to that of its prokaryotic homolog, CorA of Salmonella typhimurium, whose expression did not markedly change under various conditions.5 Nevertheless, morphogenesis may be influenced by tmg-4 expression; however, the degree of expression change is marginal. Transcriptional profiling of the wild type vegetative cultures grown on three major monosaccharides, namely D-glucose, D-xylose, and L-arabinose, revealed that NCU03312.5, NCU09091.5, and NCU11312.5 (tmg-1, tmg-2, and tmg-3) have two to three-fold more reads/RPKM values than tmg-4.35 On the other hand, transcriptional profiling of the whole genome of N. crassa before and after crossing was investigated, which revealed that NCU07816.5 had the highest expression among magnesium transporters.36 In our study, this locus was identified as tmg-4, and the expression results imply that this gene may be required for the proper development of the sexual cycle in N. crassa.

In summary, we conclude that the G-M-N motif has a high degree of conservation in CorA magnesium transporters in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. A second conserved residue of GMN, methionine, can be functionally replaced by glutamine to form a GQN motif in the Tmg-4 transporter protein of tmg-4 gene. Based on the experimental approaches, Tmg-4 with a novel motif (GQN) may serve as a magnesium transporter and may play a role in sexual reproduction in N. crassa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Department of Biotechnology for providing the necessary facilities to carry out the work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

PK conceptualized the study, acquired funding, performed supervision and project administration. SRS collected resources. SR and PK designed the experiments. SR applied methodology, performed investigation and validation. NG performed formal analysis and data curation. UKB performed visualization. NG, UKB, PK and SRS wrote the manuscript. NG, UKB and SRS reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Science and Engineering Research Board, Government of India (grant SB/YS/LS-84/2013).

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Kretsinger, RH. Magnesium in Biological Systems. In Kretsinger, RH, Uversky VN, Permyakov, EA (eds.), Encyclopedia of Metalloproteins, Springer, New York, N.Y. 2013:1250-1255.

Crossref - Anastassopoulou J, Theophanides T. Magnesium-DNA interactions and the possible relation of magnesium to carcinogenesis. Irradiation and free radicals. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;42(1):79-91.

Crossref - Cowan JA. Metal activation of enzymes in nucleic acid biochemistry. Chem Rev. 1998;98(3):1067-1088.

Crossref - Elin RJ. Magnesium: The fifth but forgotten electrolyte. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102(5):616-622.

Crossref - Maguire ME. Magnesium transporters: Properties, regulation and structure. Front Biosci Land. 2006;11(3):3149-3163.

Crossref - Eshaghi S, Niegowski D, Kohl A, Molina DM, Lesley SA, Nordlund P. Crystal structure of a divalent metal ion transporter CorA at 2.9 angstrom resolution. Science. 2006;313(5785):354-357.

Crossref - Lunin VV, Dobrovetsky E, Khutoreskaya G, et al. Crystal structure of the CorA Mg2+ transporter. Nature. 2006;440(7085):833-837.

Crossref - Szegedy MA, Maguire ME. The CorA Mg2+ transport protein of Salmonella typhimurium. Mutagenesis of conserved residues in the second membrane domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(52):36973-36979.

Crossref - Palombo I, Daley DO, Rapp M. Why is the GMN motif conserved in the CorA/Mrs2/Alr1 superfamily of magnesium transport proteins? Biochemistry. 2013;52(28):4842-4847.

Crossref - MacDiarmid CW, Gardner RC. Overexpression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae magnesium transport system confers resistance to aluminum ion. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(3):1727-1732.

Crossref - Gregan J, Bui DM, Pillich R, Fink M, Zsurka G, Schweyen RJ. The mitochondrial inner membrane protein Lpe10p, a homologue of Mrs2p, is essential for magnesium homeostasis and group II intron splicing in yeast. Mol Gen Genet. 2001;264(6):773-781.

Crossref - Weghuber J, Dieterich F, Froschauer EM, Svidovà S, Schweyen RJ. Mutational analysis of functional domains in Mrs2p, the mitochondrial Mg2+ channel protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS J. 2006;273(6):1198-1209.

Crossref - Pisat NP, Pandey A, MacDiarmid CW. MNR2 regulates intracellular magnesium storage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2009;182(1):874-884.

Crossref - Grognet P, Lalucque H, Silar P. The PaAlr1 magnesium transporter is required for ascospore development in Podospora anserina. Fungal Biol. 2012;116(10):1111-1118.

Crossref - Reza MH, Shah H, Manjrekar J, Chattoo BB. Magnesium uptake by cora transporters is essential for growth, development and infection in the rice blast fungus magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e159244.

Crossref - Suo CH, Ma LJ, Li HL, et al. Investigation of Cryptococcus neoformans magnesium transporters reveals important role of vacuolar magnesium transporter in regulating fungal virulence factors.Microbiologyopen.2018;7(3):e00564.

Crossref - Prasad D, Verma N, Bakshi M. et al. Functional characterization of a magnesium transporter of root endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica. Front Microbiol. 2019;9:3231.

Crossref - Mohamadi SF, Babaeian Jelodar N, Bagheri N, Nematzadeh G, Hashemipetroudi SH. New insights into comprehensive analysis of magnesium transporter(MGT) gene family in rice(Oryza sativa L.). 3 Biotech. 2023;13(10):322.

Crossref - Chen J, Li LG, Liu, ZH, et al. Magnesium transporter AtMGT9 is essential for pollen development in Arabidopsis. Cell Res. 2009;19(7):887-898.

Crossref - Tang Y, Yang X, Li H, et al. Uncovering the role of wheat magnesium transporter family genes in abiotic responses. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1078299.

Crossref - Sireesha R, Neelima G, Udaykumar B, Someswar RS, Premsagar K. In silico analysis of CorA superfamily magnesium transporters of fungi and identification of magnesium transporter STMg with GQN motif from Neurospora crassa. Global Journal For Research Analysis. 2023;12(9).

Crossref - Mohan PM, Sastry KS. Interrelationships in trace-element metabolism in metal toxicities in nickel-resistant strains of Neurospora crassa. Biochem J. 1983;212(1):205-210.

Crossref - Westergaard M, Mitchell HK. Neurospora V. A Synthetic Medium Favoring Sexual Reproduction. Am J Bot. 1947;34(10):573-577.

Crossref - Colot HV, Park G, Turner GE, et al. A high-throughput gene knockout procedure for Neurospora reveals functions for multiple transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103(27):10352-10357.

Crossref - Ryan FJ, Beadle GW, Tatum EL. The tube method of measuring the growth rate of Neurospora. Am J Bot. 1943;30(10):784-799.

Crossref - Kucharski LM, Lubbe WJ, Maguire ME. Cation hexaammines are selective and potent inhibitors of the CorA magnesium transport system. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(22):16767-16773.

Crossref - Nelson MA, Kang S, Braun EL, et al. Expressed sequences from conidial, mycelial, and sexual stages of Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Biol. 1997;21(3):348-363.

Crossref - Nelson MA, Metzenberg RL. Sexual development genes of Neurospora crassa. Genetics. 1992;132(1):149-162.

Crossref - Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:365-386.

Crossref - Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402-408.

Crossref - Ishijima S, Shiomi R, Sagami I. Functional analysis of whether the glycine residue of the GMN motif of the Arabidopsis MRS2/MGT/CorA-type Mg2+ channel protein AtMRS2-11 is critical for Mg2+ transport activity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2021;697:108673.

Crossref - Regon P, Chowra U, Awasthi, JP, Borgohain P, Panda SK. Genome-wide analysis of magnesium transporter genes in Solanum lycopersicum. Comput Biol Chem. 2019;80:498-511.

Crossref - Huang K, Chen X, Liu T, et al. Identification, and functional and expression analyses of the CorA/MRS2/MGT-type magnesium transporter family in maize. Plant and Cell Physiol. 2016;57(6):1153-1168.

Crossref - Worlock AJ, Smith RL. ZntB is a novel Zn2+ transporter in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(16):4369-4373.

Crossref - Li J, Lin L, Li H, Tian C, Ma Y. Transcriptional comparison of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa growing on three major monosaccharides D-glucose, D-xylose and L-arabinose. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7(31):6.

Crossref - Lehr NA, Wang Z, Li N, Hewitt DA, Lopez-Giraldez F, Trail F, Townsend JP. Gene expression differences among three Neurospora species reveal genes required for sexual reproduction in Neurospora crassa. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110398.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2023. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.