ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) were extracted from the red macroalga Gracilaria edulis through sequential chemical treatments involving alkalization, bleaching, and acid hydrolysis. The progressive removal of non-cellulosic components resulted in a milky white, gel-like CNC suspension, indicating successful isolation. The structural and morphological properties of the obtained CNCs were examined using FTIR, SEM, and XRD techniques. FTIR spectra confirmed the presence of characteristic cellulose functional groups, including O-H, C-H, and C-O-C vibrations, demonstrating the effective purification of cellulose. SEM analysis revealed a clear transformation from aggregated fibrous structures to well-defined platelet-like nanocrystals at higher magnifications (up to 30,000X), confirming nanoscale morphology. XRD patterns exhibited prominent diffraction peaks corresponding to cellulose I, with a high crystallinity index of 91.3%, indicating efficient removal of amorphous regions during acid hydrolysis. Overall, the findings demonstrate that Gracilaria edulis is a promising and sustainable marine resource for producing highly crystalline cellulose nanocrystals suitable for advanced material applications.

Gracilaria edulis, Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC), Seaweed, Acid Hydrolysis, Characterization

In contemporary society, the utilisation of eco-friendly, renewable, and sustainable materials has gained significant importance in the manufacturing of diverse high-value products that exert minimal impact on the environment.1 Among all natural and biopolymers, cellulose is the most prevalent and promising contender. It is a renewable, adaptable, and biodegradable substance that is present in bacteria, algae, plants, and tunicates.2 Algae represent a significant reservoir of biomass that is largely underexploited compared to terrestrial plants, especially in the context of applications involving cellulose-based materials.3 Predominantly, algae are grown for the creation of biofuel by making use of the oil extracted from the algae. Nevertheless, the leftover portion of the algae, often referred to as ‘waste’ or algae biomass residue (ABR), poses challenges for waste management in the environment.4

Seaweeds are favoured over terrestrial plants as a source of cellulose because they are found in terrestrial plants, often contain lignin, which increases processing costs, and they are a renewable supply of biochemical components that are employed in a variety of industries and medical disciplines, mainly for fuel and sustenance. In contrast, most species of seaweed lack true lignin, resulting in the availability of purer cellulose fractions.5 Employing nano-structuring techniques, cellulose is obtained from cellulose-rich sources in multiple forms, including fibres, microfibers, microfibrils, nanofibers, and nanocrystals.6 Cellulose is a timeless biomaterial, prevalent in the biosphere. It has been utilised for millennia in weaving, ceramics, textiles, cordage, clay bricks, and as a fuel source.7

The application of algae as an additive within the packaging sector was constrained by the insufficient understanding of its characteristics as a natural fibre within the polymer network. However, algae have been utilised for several years in the healthcare, food technology, farming, and beauty product industries and are recognised as a beneficial source of various micronutrients.8

These algal residues can be used as the source of cellulose material for extracting cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs). CNCs are a type of harmless bio-filler and strengthening agent, featuring a well-organised crystalline structure and outstanding physical properties.9 Cellulose nanocrystals are extensively utilised in polymer composites due to their high crystallinity, which results in a Young’s modulus of approximately 150 GPa and a tensile strength of 10 GPa. These nanocrystals possess surface charge, exhibit chiral nematic and amphiphilic characteristics, and are effective in altering the rheological, optical, and electrical properties of polymers. Although they have hydrophilic surfaces, they do not absorb water.7 Numerous studies have been released affirming that CNCs are environmentally benign, biologically safe, and naturally degradable, and their application as a bio-filler significantly influences the advancement of bio-composites.9

Gracilaria edulis is a type of seaweed known for its thick and juicy thallus. It often presents a dark purplish-red shade and may look sleek. The thallus consists of closely clustered small branches that are smooth or hairy. These branches are generally around 1 mm wide and commonly possess a dichotomous branching pattern. This species also features a small, round holdfast that serves to secure the algae to the surface.10 Feedstock of G. edulis, sap have been extracted from freshly harvested biomass as an agricultural byproduct (plant bio-stimulant). The plant bio-stimulant obtained from seaweed feedstock has been shown to greatly enhance yield, whether measured by biomass weight.11 The existence of crucial amino acids, lipids, and micronutrients, along with its characteristic as a thickener, allows food-grade agar derived from G. edulis to be utilised in the production of a variety of agar-based items like films, pastes and gels.10 Usage of nanosized cellulose has become increasingly popular, particularly within industrial and biomedical applications.12

While cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) have been widely extracted from various terrestrial and aquatic sources such as wood, plants, vegetables, fruits, and microalgae, there is a notable lack of research focusing on marine red algae, particularly Gracilaria edulis, as a source of CNC. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have reported the isolation and characterization of CNCs from Gracilaria edulis, highlighting a significant gap in the current literature and offering a promising avenue for exploring alternative, sustainable biomass sources for nanocellulose production.

This research seeks to extract cellulose nanocrystals from Gracilaria edulis and analyse their Morphological, crystallographic, and functional group analysis, suggesting marine biomass as a viable and sustainable alternative source.

Collection of Samples

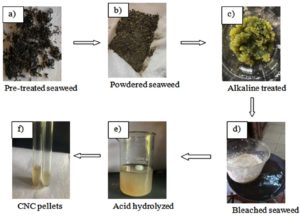

Gracilaria edulis red algae biomass was collected from the cultivational site Ramanathapuram, Tamil Nadu, India (9°16’30.3″N 79°08’36.2″ E). The live seaweed was cultivated in the laboratory with the help of artificial seawater, prepared according to the method described by Kaladharan.13 Such algae were dried for the extraction of cellulose (Figure 1).

Chemicals and materials

Chemicals such as 2% NaOH for alkalization, 30% H2O2 for bleaching, 64% of H2O2 for acid hydrolysis, 1% NaOH for neutralisation, a weigh balance, water bath, pH paper, Temperature probe, Glassware, and centrifuge.

Synthesis of CNC

The biomass was washed repeatedly with distilled water for the removal of dirt and contamination on the fibre’s surface, then dried at 50 °C for 10 min in a micro-oven. The dry weight was weighed as 25 g. The dried fibres were then finely ground into powder by using a commercial homogeniser. The isolation of cellulose nanocrystals CNC involves three major treatment steps: Alkalization, Bleaching, and Acid Hydrolysis.14 The finely ground algae biomass powder was treated with 2% NaOH solution at 80 °C for 2 hrs in a water bath. This was carried out to break the bundles of fibres into individual fibres. After the alkalization, the alkali-treated seaweeds were filtered from the solvent and stored for further processing, which weighed 120 g. The alkali-treated seaweeds were further treated with 30% Hydrogen peroxide for bleaching. Bleaching processes were done for the reduction of lignin and hemicellulose. The bleaching treatment of samples was carried out by a 30% H2O2 solution at 80 °C for 1 hrs 30 min. The bleached seaweed was filtered using the centrifuge from the bleaching solvent. The samples were centrifuged until the clear bleached pellets were obtained. The weight of bleached seaweed is about 70 g, and it shows a snowy white colour. Ten grams of bleached cellulosic material was dispersed in 1000 mL of 64 wt% sulphuric acid with continuous stirring. It is taken as 100 ml for 1 g as the constant protocol. The hydrolysis reaction was performed at 45 °C for 30 min. After these chemical reactions, the suspension was centrifuged in order to eliminate the excess sulphuric acid. The extracted cellulose is said to be the cellulosic nanocrystal (CNC).

Such extracted pellets show a pH of 1, which is acidic. For the neutralisation, 1% of NaOH is gradually added until the suspension is neutralised. After neutralising, the suspension is centrifuged to attain the cellulose nanocrystals in pellet form.6

Characterization of CNC

FTIR – Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

The chemical functional groups involved in the interaction were examined using infrared spectroscopy. FTIR spectra were obtained using a Spectrum 65 FTIR spectrometer (PerkinElmer Co., Ltd., MA, USA) over a range of 400-4000 cm-1, with 16 scans conducted. The samples were prepared and analysed in the form of KBr pellets.15

SEM – Scanning Electron Microscope

The morphological structure of the sample surfaces was examined by (OPERATOR- JEOL INSTRUMENT JSM-IT200) scanning electron microscope (JEOL, Mexico City, Mexico) operated at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. Before imaging, the samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold to enhance surface conductivity and imaging quality.16

XRD – X-ray Diffraction

The crystalline structure of the sample was examined through X-ray diffraction utilizing an BRUKER-binary V4 apparatus, Germany, which operates with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) over a 2θ range from 10.0000° to 80.0000° with a step size of 0.0400° and a scan step time of 13.4400 sec at settings of 40 kV and 40 mA. The following equation was employed to calculate the crystallinity index: CrI (%) = (I200 × Iam) / I200 × 100, where I200 represents the maximum intensity of the 200 lattice diffraction peak at 2θ = 22.5°, and Iam denotes the intensity of the diffraction corresponding to the amorphous component at 2θ = 18.5°.15

Synthesis of CNC

The pretreated seaweeds were dried (Figure 2a) and powdered (Figure 2b), which weighed 25 g, were carried out for the alkalization process. The alkaline-treated seaweeds were weighed at 120 g. The colour turned green, and their texture and size also changed as the bead’s structure (Figure 2c).

The alkali-treated algae were bleached with hydrogen peroxide. As a result of bleaching, the bead-like structured compound was loosened and dispersed in the solvent. It shows a milky white colour (Figure 2d). And that weighs about 70 g.

The bleached seaweed cellulose was filtered from the bleaching solvent and further processed through acid hydrolysis treatment. The bleached algal cellulose gets dissolved finely in the acid (Figure 2e). The acid-treated cellulose was centrifuged, and the pellets were collected.

The pH of the acid-treated cellulose was noted as 1. In order to neutralise the extract, it is treated with sodium hydroxide to attain the normal pH. The neutralised cellulose materials were centrifuged, and the pellets were collected. The collected cellulose is in the form of a jelly-like suspension (Figure 2f).

Characterization of CNC

FTIR

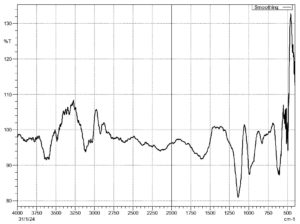

The FTIR analysis was performed for the cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) isolated from Gracilaria edulis used in this investigation. It is done for the identification of functional groups. The spectra were recorded and interpreted according to their peaks in Figure 3. The peak at 1050-1080 cm-1 represents the presence of the C-O-C group. The 2900 cm-1 is ascribed to the C-H stretching. The broad absorption at 3400-3600 cm-1 is attributed to the stretching vibration of -OH groups. The peak at 1550-1600 cm-1 is related to the bending mode of the water molecule resulting from a strong interaction between water and cellulose.

Figure 3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of cellulose nanocrystals of Gracilaria edulis

SEM

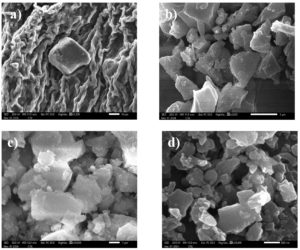

Scanning Electron Microscopy is used to examine the surface morphology of CNC. Under a 1,000x magnification, a wrinkled matrix containing a fibrous, entangled network of partially aggregated CNCs is visible (Figure 4a). Under 5000x magnification, crystalline cellulose regions are indicated by a dense aggregation of irregularly geometrized plate-like particles (Figure 4b). A 10,000x magnification shows closely spaced crystallites that are smaller and have better surface definition (Figure 4c). 30,000x magnification reveals distinct, platelet-like CNC morphologies, proving their identity at the nanoscale (Figure 4d).

Figure 4. Denotes the SEM images of CNC of Gracilaria edulis at different magnifications (a) 1000x (b) 5000x (c) 10,000x and (d) 30,000x

XRD

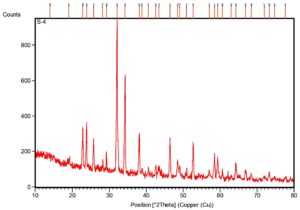

The XRD pattern shows distinct peaks that match the Cellulose I (Figure 5). Key peaks were found at 2θ = 22.87° and 23.83°, linked to the (200) plane of Cellulose I, with a smaller peak at 19.09°. The strongest peak appeared at 2θ = 32.09° and another notable peak at 34.25°, associated with the (004) plane. These results suggest a clear crystalline structure. The Crystallinity Index (CrI) of the CNCs was about 91.3%, indicating effective removal of amorphous regions during the acid hydrolysis process.

The current investigation applied sequential chemical processes, including alkalization, bleaching, and acid hydrolysis, to pre-treated seaweeds to extract purified cellulose. Post-alkali treatment processes resulted in a distinctive green colouration coupled with a textural shift to bead-like formations. Previous research demonstrated that alkali treatment causes partial dissociation of algal fibres through cleavage of alkali-labile linkages between lignin monomers and polysaccharides.14 The bead-like structure from our study indicates potential unique morphological rearrangements that may occur due to specific seaweed species or processing conditions. The alkali-treated material, when subjected to hydrogen peroxide bleaching, lost its bead-like structure and dispersed into the solvent, achieving a milky white appearance.6 The present study documented how bleaching processes caused fibre defibrillation while eliminating residual lignin to produce pure cellulose, which manifested as a bright white material. The observed yield variation from 25 g of raw material to 70 g of bleached cellulose results from the material’s expansion and water incorporation during chemical treatments. Upon neutralisation the final acid hydrolysis step dissolved bleached cellulose to create a jelly-like suspension, which indicated nanoscale cellulose dispersion. The sequential treatments demonstrate their capability to dismantle the cell wall matrix while achieving cellulose isolation in finely divided particulate form.

FTIR was used to analyse and detect the functional groups in cellulose fractions obtained from Ulva fasciata, Cystoseira sinuosa, and Acanthophora rigida.5 The spectra showed characteristic peaks at 3336-3442 cm-1 (O-H stretching), 2921-2923 cm-1 (C-H stretching), 1650-1664 cm-1 (bound H₂O), 1425-1430 cm-1 (C-H bending), and 1030-1059 cm-1 (C-O-C bending), confirming the typical cellulose functional groups. Structural changes between cellulose and cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) from seaweeds were studied using FTIR.17 They found consistent chemical structures across different seaweeds, with peaks at 1440,1160, and 898 cm-1 confirming cellulose I. The disappearance of peaks near 890 cm-1 in CNCs indicated the removal of amorphous regions due to acid hydrolysis. Following these studies, FTIR analysis was also carried out on CNCs isolated from Gracilaria edulis in this study to identify functional groups. The spectra showed a broad absorption band between 3400 and 3600 cm-1, linked to O-H stretching vibrations, suggesting strong hydrogen bonding. A peak around 2900 cm-1 corresponded to C-H stretching, while a peak between 1050 and 1080 cm-1 was assigned to C-O-C stretching vibrations, confirming the presence of cellulose. Additionally, a peak from 1550-1600 cm-1 was related to the bending mode of water molecules, likely due to strong interactions between water and cellulose. These features confirm the successful isolation of CNCs and the maintained structure of the cellulose backbone, while also showing a decrease in amorphous content caused by acid hydrolysis.

Progressive magnifications offered a detailed view of surface features and nanostructures evolved during the isolation process. At 1,000× magnification, the CNC sample showed a wrinkled matrix mixed with fibrous, tangled networks, indicating partial aggregation. This structure matches the leftover cellulose framework after the initial breakdown of bulk fibres. At 5,000× magnification, areas of crystalline cellulose became visible as dense clusters of irregular, plate-like particles. At 10,000×, smaller, closely packed crystallites with more refined surface details appeared, suggesting higher purity and better nanoscale definition. Finally, at 30,000× magnification, individual platelet-like nanocrystals were clearly seen, confirming the successful isolation of CNCs at the nanoscale. These features suggest the treatment effectively broke down the amorphous regions and exposed the crystalline parts of cellulose.

These findings align with earlier studies on C. linum, which showed a gradual breakdown of biomass into cellulose-rich components through chemical treatments. Previous SEM analyses by Cai and Zhang, Ke et al, Qi et al, Sgriccia et al.18-21 described C. linum biomass as having a rough texture with coiled cellulose and fat-like materials around uneven cores. This has been linked to intracrystalline swelling of cellulose fibres, which increases access to internal hydroxyl groups for further chemical reactions.

The XRD analysis of CNCs isolated from Gracilaria edulis showed clear peaks typical of the Cellulose I crystalline structure. Strong diffraction peaks appeared at 2θ = 22.87° and 23.83°, corresponding to the (200) lattice plane of Cellulose I. A smaller peak was also seen at 2θ = 19.09°, along with sharp peaks at 2θ = 32.09° and 34.25°, the latter linked to the (004) plane. The crystallinity index (CrI) was about 91.3%, indicating a high level of crystalline order and effective removal of amorphous parts during acid hydrolysis. These results agree with previous studies that reported peaks near 2θ = 18°, 22°, and 34° as typical of cellulose I structure.22-27 The presence of sharp, well-defined peaks, especially at the (200) plane, reflects the enhanced crystallinity of the CNCs relative to untreated cellulose, supporting the view that acid hydrolysis promotes the formation of highly ordered crystalline domains. Additionally, peaks at 2θ = 25° and 34° have been linked to trimethylcellulose and native cellulose, supporting the classification of the CNCs as cellulose I.25 The strong reflections at 22.87° and 23.83° confirm that Cellulose I is the dominant polymorph in the CNCs derived from Gracilaria edulis.

This study successfully demonstrates the extraction and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) from the red marine algae Gracilaria edulis. Based on existing studies, this is the first report detailing the extraction and characterization of CNCs from Gracilaria edulis, addressing a notable gap in existing research on marine algae-derived nanocellulose. Sequential chemical treatments—alkalization, bleaching, and acid hydrolysis effectively isolated cellulose, as evidenced by morphological, structural, and spectral analyses. The FTIR spectra confirmed the preservation of key cellulose functional groups, indicating successful isolation and minimal degradation of cellulose chains. SEM imaging revealed well-defined, platelet-like nanostructures, corroborating the successful synthesis of nanoscale cellulose. Furthermore, XRD analysis showed a high crystallinity index (CrI ~91.3%) and confirmed the dominance of the Cellulose I polymorph, affirming the effectiveness of the acid hydrolysis process in removing amorphous regions. The outcomes validate Gracilaria edulis as a viable and eco-friendly alternative source of CNCs with promising properties suitable for various industrial applications, including biocomposites, biomedical materials, and packaging. This research not only addresses the environmental challenge of seaweed biomass waste management but also opens new avenues for valorizing marine resources within the circular bioeconomy framework. Future studies should focus on scaling the extraction process, assessing biocompatibility for biomedical use, and integrating CNCs into polymer matrices to evaluate their reinforcement potential.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Department of Microbiology, Annamalai University, and the Senior Research Scholars and Lab Assistants for their support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Trache D, Tarchoun AF, Derradji M, et al. Nanocellulose: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications. Front Chem. 2020;8:392.

Crossref - Emenike EC, Iwuozor KO, Saliu OD, Ramontja J, Adeniyi AG. Advances in the extraction, classification, modification, emerging and advanced applications of crystalline cellulose: A review. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2023;6:100337.

Crossref - Mihhels K, Yousefi N, Blomster J, Solala I, Solhi L, Kontturi E. Assessment of the Alga Cladophora glomerata as a Source for Cellulose Nanocrystals. Biomacromolecules. 2023;24(11):4672-4679.

Crossref - Chen L, Liu T, Zhang W, Chen X, Wang J. Biodiesel production from algae oil high in free fatty acids by two-step catalytic conversion. Bioresour Technol. 2012;111:208-214.

Crossref - Salem DMSA, Ismail MM. Characterization of cellulose and cellulose nanofibers isolated from various seaweed species. Egypt J Aquat Res. 2022;48(4):307-313.

Crossref - El Achaby M, Kassab Z, Aboulkas A, Gaillard C, Barakat A. Reuse of red algae waste for the production of cellulose nanocrystals and its application in polymer nanocomposites. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;106:681-691.

Crossref - Shojaeiarani J, Bajwa DS, Chanda S. Cellulose nanocrystal based composites: A review. Compos Part C Open Access. 2021;5:100164.

Crossref - Mondal K, Sakurai S, Okahisa Y, Goud VV, Katiyar V. Effect of cellulose nanocrystals derived from Dunaliella tertiolecta marine green algae residue on crystallization behaviour of poly(lactic acid). Carbohydr Polym. 2021;261:117881.

Crossref - Sucaldito MR, Camacho DH. Characteristics of unique HBr-hydrolyzed cellulose nanocrystals from freshwater green algae (Cladophora rupestris) and its reinforcement in starch-based film. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;169:315-323.

Crossref - Bhushan S, Veeragurunathan V, Bhagiya BK, Krishnan SG, Ghosh A, Mantri VA. Biology, farming and applications of economically important red seaweed Gracilaria edulis (S. G. Gmelin) P. C. Silva: A concise review. J Appl Phycol. 2023;35(3):983-996.

Crossref - Singh S, Singh MK, Pal SK, et al. Sustainable enhancement in yield and quality of rain-fed maize through Gracilaria edulis and Kappaphycus alvarezii seaweed sap. J Appl Phycol. 2016;28(3):2099-2112.

Crossref - Murugesan S, Radhika RSR, Rajan R. Extraction and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from brown seaweed Dictyota bartayreisana, J.V.Lamouroux. In Review. 2024.

Crossref - Kaladharan P. Artificial seawater for seaweed culture. Indian J. Fish. 2000;47(3):257-259

- Miri NE, Abdelouahdi K, Zahouily M, et al. Bio-nanocomposite films based on cellulose nanocrystals filled polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan polymer blend. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2015;132(22).

Crossref - Singh S, Gaikwad KK, Park SI, Lee YS. Microwave-assisted step reduced extraction of seaweed ( Gelidiella aceroso) cellulose nanocrystals. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;99:506-510.

Crossref - Manzano LMG, Cruz MÁR, Tun NMM, González AV, Hernandez JHM. Effect of Cellulose and Cellulose Nanocrystal Contents on the Biodegradation, under Composting Conditions, of Hierarchical PLA Biocomposites. Polymers. 2021;13(11):1855.

Crossref - Doh H, Dunno KD, Whiteside WS. Cellulose nanocrystal effects on the biodegradability with alginate and crude seaweed extract nanocomposite films. Food Biosci. 2020;38:100795.

Crossref - Cai J, Zhang L. Rapid Dissolution of Cellulose in LiOH/Urea and NaOH/Urea Aqueous Solutions. Macromol Biosci. 2005;5(6):539-548.

Crossref - Ke H, Zhou J, Zhang L. Structure and physical properties of methylcellulose synthesized in NaOH/urea solution. Polym Bull. 2006;56(4-5):349-357.

Crossref - Qi H, Liebert T, Meister F, Heinze T. Homogenous carboxymethylation of cellulose in the NaOH/urea aqueous solution. React Funct Polym. 2009;69(10):779-784.

Crossref - Sgriccia N, Hawley MC, Misra M. Characterization of natural fiber surfaces and natural fiber composites. Compos Part Appl Sci Manuf. 2008;39(10):1632-1637.

Crossref - Chen YW, Lee HV, Juan JC, Phang SM. Production of new cellulose nanomaterial from red algae marine biomass Gelidium elegans. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;151:1210-1219.

Crossref - Liu Z, Li X, Xie W, Deng H. Extraction, isolation and characterization of nanocrystalline cellulose from industrial kelp (Laminaria japonica) waste. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;173:353-359.

Crossref - Mandal A, Chakrabarty D. Isolation of nanocellulose from waste sugarcane bagasse (SCB) and its characterization. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;86(3):1291-1299.

Crossref - Park S, Baker JO, Himmel ME, Parilla PA, Johnson DK. Cellulose crystallinity index: measurement techniques and their impact on interpreting cellulase performance. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2010;3(1):10.

Crossref - Sung SH, Chang Y, Han J. Development of polylactic acid nanocomposite films reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals derived from coffee silverskin. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;169:495-503.

Crossref - Van Hai L, Son HN, Seo YB. Physical and bio-composite properties of nanocrystalline cellulose from wood, cotton linters, cattail, and red algae. Cellulose. 2015;22(3):1789-1798.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.