ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Salt lakes represent an extreme habitat for prokaryotes which tolerate significant concentration of NaCl. Many studies on screening and characterization of these microorganisms have been done, however, very little reported about urease producer halophilic bacteria. The present study aimed to isolate urease positive bacteria from Bahr Al-Milh Salt Lake, Karbala, Iraq. A total of 161 gram positive and 57 gram negative bacteria were found which one third of them showed the ability to produce urease. 16S rDNA sequencing analysis showed the isolated bacteria belong to genus Bacillus, Virgibacillus, Halobacillus and Staphylococcus. Further studies focusing on the enzyme structures and encoding genes are suggested.

Halophiles, Iraq, Urease, Screening.

Halophiles are extreme microorganisms manifesting special characteristics made them an interesting subject in recent biotechnological researches1. Indeed, not only halophiles can tolerate NaCl-saturated environments but also some of them require specific amount of salt for their survival2. The most observed halophile communities are from Archaea and Bacteria that would be found in saline lakes, saline soils and brines3. Living in extreme environments has enabled these creatures to develop mechanisms through which they produce special metabolites and biomolecules4. Exopolyssaccharides, carotenoid pigments and bacteriorhodopsin are some examples of halophilic biomolecules which have been studied and applied in industrial processes5. Regarding to biotechnological applications, halophiles have been widely used in producing Beta-carotene and also ectoine, a compound derived from moderately halophilic bacteria functioning as enzyme stabilizer6. Production of compatible solutes, drug screening, cancer detection and the biodegradation of residues and toxic compounds are considered as other potential or present halophiles’ applications5. Many forms of bioactive compounds with various biological activities like antioxidants, sunscreen and antibiotic actions are derived from them7-9. Furthermore, halophiles are the major source of enzymes functioning in high salt concentration without being aggregated or denatured5.

Urease is a cytosolic enzyme founded in various bacteria, plants and fungi10-13. It is the first known nickel metalloenzyme and also the first enzyme isolated in the form of crystalline protein14. Urease activity involves in nitrogen cycle; it is an effective enzyme in urea hydrolysis–as a nitrogen source–to ammonia and carbon dioxide10. Microbial urease is a virulence factor in pathogenic bacteria accounted for many clinical conditions like urinary stones, pyelonephritis, gastric ulceration, and other diseases15. Despite these negative effects, urease has a wide range of medical, biotechnological and agricultural applications. It has the major role in recycling urea nitrogen in ruminal and gastrointestinal microorganisms which benefits the host and the microbe10. Additionally, it is important in transforming specific nitrogen compounds. Hence, urease activity represents an index of pathogenic potential and also drug resistance in some bacterial groups16.

On the other side, urease has a significant role in nitrogen metabolism in soil and aquatic environments and also enables microorganisms to utilize internal and externally generated urea as nitrogen source10. The produced ammonia is taken up by soil and plant microbes which highlight usage of urease fertilizers. Low cost, ease in handling and doubled nitrogen content are the main reasons for universal shift from nitrogen to urease fertilizers17.

Bahr Al-Milh Salt Lake located 10 kilometers west of Karbala, Iraq. Together with dwindling water level in recent decades, salt concentration and pH value of the Lake has raised. With our knowledge, limited studies have been published only about eukaryotic diversity of the Lake18. It has recently been considered as an extreme ecosystem including halophilic microorganisms19. In present study, we evaluated the urease activity of halophilic bacteria in Bahr Al-Milh Salt Lake for the first time.

Sampling and preparations

Preferred amount of mud and saline alluvial soil was sampled from eastern parts of the Bahr Al-Milh, west of Karbala, Iraq, in the longitude of 43° 85′ E and the latitude of 32°60′ N on February, 2014. Temperature of the area was between 20 to 25°C. Samples were transported to microbiology laboratory in sterile and labeled plastic bags. The strains were grown in different saline concentration of nutrient broth, from 2.5% to 22.5% with 2.5 intervals, containing Artificial Sea Water (ASW) with the following composition: 175g NaCl, 20 g MgCl2.6H2O, 5 g K2SO4, and 0.1 g CaCl2 and 2 ml filtered saline lake water as the trace element. Final volume was then reached to 1 liter with distilled water. pH 7 and greater (7.5, 8.0 and 8.5) was provided with the addition of NaOH. The culture medias were autoclaved and then incubated at 37°C for a week. One ml of each sample was transferred to nutrient agar medium with the same saline concentrations where they grew for another one week. Number of colonies was counted following by two weeks’ further incubation. Gram staining and KOH lysis tests were performed like pervious reports20-21. Morphology of the cells was studied using light microscopy (model BH2; Olympus).

Enzymatic activities

Catalase production was determined by adding 3% (v/v) H2O2‚ and observing its hydrolysis and the consequent gas formation22. The oxidase activity was detected according to Kovacs (1956)23. Utilization of glucose and sucrose as carbon sources as well as acid production from them, was performed as recommended by Ventosa et al. (1982)24. According to Stuart’s Urea Broth test, urease activity was determined by dissolving 0.1 g yeast extract, 9.1 g potassium phosphate monobasic, 9.5 g potassium phosphate dibasic,

20 g urea and 0.01 g phenol red in 1 litter of distilled water and filter sterilize. Observation of red color in yellow-orange media after one week incubation was considered as positive urease activity25.

Molecular analysis

The DNA was extracted and purified using Bioron sample preparation Kit-Korea. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR run with two universal bacterial primers: 8F (5’AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’) and 1492R (5’GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-m3’). PCR solution contained 5 µl template DNA, 17 µl dH2O, 1 µl primers, 1 µl dNTP, 0.75 µl MgCl2 (50mM), 25 µl PCR amplification buffer (1X), and 2 U Taq DNA polymerase. Amplification was carried out with Techne TC-3000X Thermal cycler (UK) as follow: initial denaturation at 95°C for five minutes, followed by 30 one-minute cycles at 95°C, 30 s at 58°C, one minute at 72°C and 10 minutes at 72°C for the final extension. After Electrophoresing, PCR products–single 1400 bp of DNA fragments–were then purified using GeneAll Gel Extraction Kit (Korea). Sequencing of 16S rRNA was performed by Macrogen Biotechnology Company (Korea) using an automated sequencer.

The newly sequenced 16S rRNAs were aligned with BLAST and RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) and compared with alike bacterial sequences available in NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information). Drawing phylogenetic trees was completed using MEGA7 software, neighbor-joining, maximum likelihood and maximum-parsimony algorithms26-29. Bootstrap analyses based on 1000 replications determined the confidence values of the branches. 16S rRNA sequences of newly found strains were submitted in the GenBank database.

Two hundreds and eighteen halophilic strains were isolated from enrichment cultures which 31.2% (N=68) of them were known as urease producers. Optimum status of pH ranging from 7.0 to 7.5 and temperature of 37°C was obtained. No extremely halophilic bacteria were found and the frequencies of slightly and moderately halophilic isolates were 68% and 32%, respectively. In this regard, the optimum salinity for growth was 10% ASW. Majority of the strains were gram positive bacteria with the prevalence of 73.8% (N=161) and the gram negative groups comprised the remaining 26.2% (N=57). As for the morphology, they included 57.8% (N=126) of rods or short rods and 42.2% (N=92) of cocci represented in singles, pairs or short chains.

According to morphological differences, four strains were randomly selected for further molecular analysis. Characterizations of the mentioned strains are given in table 1. Catalase and oxidase were produced by all four isolates. Half of them were able to produce acid from glucose and sucrose and the same bacteria showed the ability to use the aforementioned carbohydrates as sole source of carbon.

Table (1):

Phenotypic characteristics of urease positive isolates

| Strains Characteristics | Bacillus sp. K3 | Virgibacillus sp. K11 | Staphylococcus sp. K33 | Halobacillus sp. K51 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram | + | + | + | + |

| Shape | rod | rod | cocci | rod |

| Oxidase | + | + | + | + |

| Catalase | + | + | + | + |

| Urease activity | + | + | + | + |

| Acid production from | ||||

| Glucose | + | – | + | – |

| Sucrose | + | – | + | – |

| Carbon Source utilization | ||||

| Glucose | + | – | + | – |

| Sucrose | + | – | + | – |

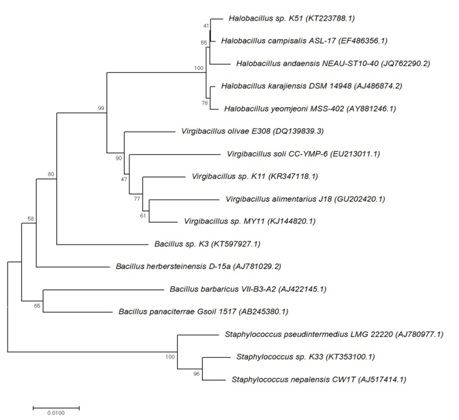

16S rRNA gene sequence analysis based on bootstrap values revealed that the urease-producing isolates belong to genus Bacillus, Virgibacillus, Halobacillus and Staphylococcus. The very partial sequences of isolates have been deposited in the GenBank database with the following accession number; KT597927, KR347118, KT223788 and KT353100, respectively. They were all gram positive and members of class Bacilli. Figure 1 presents the phylogenetic trees of the very isolates.

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic tree of the halophilic isolates showing their position based on the partial 16S rDNA sequence comparison, according to the neighbor-joining method. The number on branches indicated bootstrap values and the accession numbers for the reference strains are showed in brackets.

In a similar study from Urmia Lake, Iran, urease activity and oxidase were positive for the majority of the halophilic isolates including Salicola, Pseudomonas, Marinobacter, Idiomarina, Halomonas, Bacillus and Halobacillus30. In a purification and gene sequencing study of urease from halobacteria, only four extreme halophile strains out of 71 were found to be urease producer, mostly belong to genus Haloarcula31. Spirulina maxima was reported as a urease positive halophilic cyanobacterium32. Study of halotolerant and alkaliphilic bacteria in different climate zones (soil samples from Singapore, Ukraine and Jordan) led to characterization of Staphylococcus succinus and two Bacillus as urease-producing isolates33.

In contrast with our results, Virgibacillus kekensis sp. which was isolated from Keke Salt Lake, north-west of China, was negative for urease activity34. A same negative activity was reported for Virgibacillus salarius sp. isolated from a Saharan Salt Lake, Tunisia35. Bacillus aidingensis sp. and Halobacillus salinus sp. isolated respectively from Ai-Ding Salt Lake, China and Salt Lake of the East Sea in Korea, were not able to produce urease36-37. Whereas most non-pathogenic Staphylococcus strains were explained as strong urease producers38.

In conclusion, our findings clearly indicate that one third of halophilic bacteria in Bahr Al- Milh Salt Lake were able to produce urease. They mostly belong to the class Bacilli. The isolated strains can be used for medical, biotechnological and agricultural applications. They also have the potential to use as a source of halostable ureases in various industrial utilizations. Follow up studies considering purification of the ureases, estimating the optimum situation for maximum activity of the enzymes, investigating molecular structure and introducing the encoding genes for them are recommended.

- M. Delgado-García, B. Nicolaus, A. Poli, C. N. Aguilar, R. Rodríguez-Herrera. Isolation and Screening of Halophilic Bacteria for Production of Hydrolytic Enzymes. Sustainable Development and Biodiversity. 2015; 6: 379-401.

- J K Lanyi. Salt-Dependent Properties of Proteins from Extremely Halophilic Bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1974; 38(3): 272–290.

- A Oren. Halophilic microbial communities and their environments. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015; 33: 119-24.

- A Ventosa, RR de la Haba, C Sánchez-Porro and RT Papke. Microbial diversity of hypersaline environments: a metagenomic approach. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015; 25: 80-7.

- R Waditee-Sirisattha, H Kageyama, T Takabe. Halophilic microorganism resources and their applications in industrial and environmental biotechnology. AIMS Microbiology. 2016; 2(1): 42-54.

- A. Ventosa and J. J. Nieto. Biotechnological applications and potentialities of halophilic microorganisms. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1995; 11(1): 85–94.

- TA Hosseini and M Shariati. Dunaliella Biotechnology: methods and applications. J Appl Microbiol. 2009; 107: 14–35.

- R Waditee-Sirisattha, H Kageyama, W Sopun, Y Tanaka and T Takabe. Identification and upregulation of biosynthetic genes required for accumulation of Mycosporine-2-glycine under salt stress conditions in the halotolerant cyanobacterium Aphanothece halophytica. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014; 80: 1763–1769.

- D Chen, J Feng, L Huang, Q Zhang, J Wu, X Zhu, Y Duan and Z Xu. Identification and characterization of a new erythromycin biosynthetic gene cluster in Actinopolyspora erythraea YIM90600, a novel erythronolide-producing halophilic actinomycete isolated from salt field. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e108129.

- HL Mobley and RP Hausinger. Microbial ureases: significance, regulation, and molecular characterization. Microbiol. Rev. 1989; 53(1): 85-108.

- D Orth, K Grif, MP Dierich and R Würzner. Prevalence, structure and expression of urease genes in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichiacoli from humans and the environment. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2006; 209(6): 513-520.

- A Sirko and R Brodzik. Plant ureases: Roles and regulation. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2000; 47(4): 1189-1195.

- JJ Yu, SL Smithson, PW Thomas, TN Kirkland and GT Cole. Isolation and characterization of the urease gene (URE) from the pathogenic fungus Coccidioides immitis. Gene. 1997; 198(1-2): 387-391.

- Y Qin and JMS Cabral. Review Properties and Applications of Urease. 2002; 20(1): 1-14.

- B Sujoy and A Aparna. Enzymology, Immobilization and Applications of Urease Enzyme. Int. Res. J. Biological Sci. 2013; 2(6): 51-56.

- B Sujoy and A Aparna. Potential clinical significance of urease enzyme. European Scientific Journal. 2013; 9(21): 94-102.

- P M. Gliber, J Harrison, C Heil and S Seitzinger. Escalating worldwide use of urea – a global change contributing to coastal eutrophication. Biogeochemistry. 2006; 77(3): 441–463.

- R Kornijów, JA Szczerbowski, T Krzywosz, and R Bartel. The macrozoobenthos of the Iraqi lakes Tharthar, Habbaniya and Razzazah. Archives of Polish Fisheries. 2011; 9(1): 127-145.

- JM Salman and AJ Nasser. Variation of some physico-chemical parameters and biodiversity of gastropods species in Euphrates River, Iraq. International Journal of Environmental Science and Development, 2013; 5(3): 328-331.

- R.M. Smibert and N.R. Krieg, Phenotypic characterization. In Methods for General and Molecular Bacteriology, pp. 607–654, Edited by P. Gerhardt, R.G.E. Murray, W.A. Wood and N.R. Krieg, Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1994.

- T. Gregersen. Rapid method for distinction of Gram-negativefrom Gram-positive bacteria. European journal of applied microbiology and biotechnology. 1978; 5(2): 123-127.

- LJ Bradshaw. Laboratory Microbiology, 4th edn. Fort Worth, TX: Saunders College Publishing, 1992.

- N. Kovacs. Identiûcation of Pseudomonas pyocyanea by the oxidase reaction. Nature. 1956; 178(4535): 703–4.

- A Ventosa, E Quesada, F Rodr guez-Valera, F Ruiz-Berraquero and A Ramos-Cormenzana. Numerical taxonomy of moderately halophilic Gram-negative rods. J Gen Microbiol. 1982; 128: 1959–1968.

- CA Stuart, E Van Stratum and R Rustigian. Further studies on urease production by Proteus and related organisms J. Bacteriol. 1945; 49:437.

- K. Tamura, G. Stecher, D. Peterson, A. Filipski and S. Kumar, MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 60. Molecular Biology Evolution. 2013; 30(12): 2725-2729.

- N. Saitou and M. Nei, the neighbor joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology Evolution. 1987; 4(4): 406-425.

- J. Felsenstein, Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: amaximum likelihood approach. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1981; 17(6): 368-376.

- W.M. Fitch, “Toward defining the course of evolution: minimum change for a specific tree topology,” Systematic Zoology. 1971; 20(4): 406-416.

- SZ Vahed, H Forouhandeh, S Hassanzadeh, HP Klenk, MA Hejazi and MS Hejazi. Isolation and characterization of halophilic bacteria from Urmia Lake in Iran. Mikrobiologiia. 2011; 80(6):826-33.

- T Mizuki, M Kamekura, S DasSarma, T Fukushima, R Usami, Y Yoshida and K Horikoshi. Ureases of extreme halophiles of the genus Haloarcula with a unique structure of gene cluster. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2004; 68(2):397-406.

- N Carvajal, M Fernandez, JP Rodriguez and M Donoso. Phytochemistry. 1982; 21: 2821-2823.

- V Stabnikov, Ch Jian, V Ivanov, Y Li. Halotolerant, alkaliphilic urease-producing bacteria from different climate zones and their application for biocementation of sand. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013; 29:1453–1460.

- Y Chen, X Cui, D Fritze, L Chai, P Schumann, M Wen, Y Wang, L Xu and C Jiang. Virgibacillus kekensis sp. nov., a moderately halophilic bacterium isolated from a Salt Lake in China. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2008; 58: 647–653.

- NP Hua, A Hamza-Chaffai, RH Vreeland, H Isoda, T Naganuma. Virgibacillus salarius sp. nov., a halophilic bacterium isolated from a Saharan Salt Lake. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008; 58(Pt 10): 2409-14.

- Y Xue, A Ventosa, X Wang, P Ren, P Zhou and Y Ma. Bacillus aidingensis sp. nov., a moderately halophilic bacterium isolated from Ai-Ding Salt Lake in China. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2008; 58: 2828–2832.

- JH Yoon, KH Kang and YH Park. Halobacillus salinus sp. nov., isolated from a Salt Lake on the coast of the East Sea in Korea. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2003; 53: 687–693.

- UK Schäfer and H Kaltwasser. Urease from Staphylococcus saprophyticus: purification, characterization and comparison to Staphylococcus xylosus urease. Arch Microbiol. 1994; 161: 393-399.

© The Author(s) 2017. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.