ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

The increasing prevalence of Candida infections is a major healthcare challenge, underscoring the need for novel therapeutic agents. In this study, we evaluated the antifungal and anti-inflammatory activity of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline against various Candida and Aspergillus species using both in vitro and in vivo models. Using the broth microdilution method, 21 reference strains were evaluated, revealing notable fungicidal activity particularly against Candida glabrata and Candida krusei, while variable susceptibility was observed in C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis. However, no activity was detected against Aspergillus species. In the oral candidiasis mice model, significant antifungal efficacy was confirmed against C. albicans. Moreover, 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline exhibited pronounced anti-inflammatory effects, as evidenced by a dose-dependent reduction in pro-inflammatory markers such as IL-6, IL-1β, COX-2, iNOS, and IFN-γ (p < 0.05 at concentrations of 0.02 and 0.2 mg/mL). Taken together, these findings indicate that 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline has dual antifungal and anti-inflammatory potential, positioning it as a promising candidate for further preclinical development.

2,3-Dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline, Antifungal activity, Anti-inflammatory, Candida, Aspergillus, Drug Discovery, In vitro, In vivo

The increasing impact of fungal diseases on human health has become a significant global concern.1 Nearly one billion people suffer from fungal infections affecting the skin, nails, and hair, while tens of millions experience mucosal candidiasis. Moreover, over 150 million individuals are affected by severe fungal diseases that can be life-altering or fatal. Fungal infections are typically underappreciated and disregarded despite their substantial impact on the quality of life of people worldwide.2 These maladies range from superficial ailments, such as skin and nail conditions to life-threatening systemic fungal infections.3 Their impact is especially severe among immunocompromised individuals, such as patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy or organ transplant recipients, for whom fungal infections can markedly increase the risks of illness and death.4,5 Each year, fungal infections can potentially impact millions of individuals worldwide, with an estimated annual death toll of approximately 1,350,000.6

Recently, the emergence of highly drug-resistant Candida auris has arisen as a significant threat to global health. This pathogen is responsible for infections that are resistant to all major classes of antifungal agents and poses a particular danger to immunocompromised individuals.7

Currently, the effective management of candidiasis is limited by two primary challenges: the rapid and accurate diagnosis of the invading pathogen and the limited availability of treatment options.6 For instance, polyenes face challenges related to drug resistance, high toxicity, and a narrow therapeutic range. Furthermore, both polyenes and echinocandins exhibit limited oral bioavailability, necessitating intravenous administration along with prolonged hospitalization. Furthermore, extended-spectrum triazoles, such as posaconazole, face challenges related to variable bioavailability, acute adverse reactions, and resistance development, collectively limiting their effectiveness.4,8,9 Although polyenes have been proposed for topical application, their limited capacity to penetrate ocular tissues restricts their effectiveness in treating ocular fungal infections.10

Most antimicrobial drugs currently employed in clinical practice were initially discovered over half a century ago. In recent times, the lack of both investment and research efforts dedicated to antimicrobial discovery has greatly reduced novel drug development in this field. Therefore, the prospects for novel antimicrobial agents in the near future remain limited.11 Given the limitations of current FDA-approved antifungal drugs and challenges of developing new drugs, it is vital to identify novel antifungal compounds that exhibit reduced toxicity and improved pharmacokinetic properties.12 In line with this, the repurposing of existing drugs for new indications represents a promising strategy.13

Accordingly, Elfadil et al. demonstrated that quinoxaline derivatives, specifically 2,3-dimethylquinoxaline (DMQ), exhibit broad-spectrum antifungal activity as well as significant potential in enhancing wound healing.14 Recently, 2-chloro-3-hydrazinylquinoxaline has been reported to demonstrate potent fungicidal activity against various fungal pathogens.15 These findings collectively suggest that 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline, a related quinoxaline derivative, may exhibit similar antifungal activity owing to structural similarities.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the antifungal activity of the novel antifungal agent 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline, which exhibits promising antimicrobial properties. The efficacy of this compound against Candida and Aspergillus infections was assessed in vitro and in vivo using C. albicans ATCC 10231.

The test compound 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline (CAS No. 55686-95-8) was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich. A 10 mg/mL stock solution of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline was prepared using dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; CAS No. 67-68-5; Sigma Aldrich; Taufkirchen, Germany). The 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline working solution was diluted in RPMI-1640 medium (R7509; USA) to achieve a final DMSO concentration of less than 5%.

Fungal species, media, and growth conditions

A total of 21 fungal reference strains were used in the in vitro experiments, including pathogenic Candida species such as Candida albicans, Candida krusei, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida auris, Candida glabrata, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus brasiliensis, and Aspergillus terreus. All strains were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. For inoculum preparation, cell suspensions were adjusted to match a turbidity equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland standard, corresponding to a concentration of 1-5 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL in RPMI 1640 medium. For the in vivo experiments, C. albicans ATCC 10231 from the American-Type-Culture-Collection was used as a reference strain. The strains were preserved at -80 °C in Sabouraud’s dextrose broth supplemented with 20% glycerol solution. For culturing, the cells were streaked on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar and incubated at 37 °C for 36 h.

Formulating a 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline gel preparation

A 1% hydrogel formulation containing 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline was prepared using hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) as the gelling agent. Initially, 2 g of HPMC powder (CAS No. H7509; Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) was dispersed in 50 mL of purified hot water under continuous stirring to ensure hydration and uniform dispersion. To enhance the texture and consistency of the gel, 10 mL of glycerol (CAS No. G5516; Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) was added, and the mixture was allowed to stand. The preparation was then covered and allowed to stand undisturbed at room temperature for 24 h to allow complete swelling and the formation of a clear, viscous HPMC base gel. A 1% w/w drug-loaded hydrogel was subsequently prepared by dissolving 1 g of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline in a solvent mixture containing 5 mL of methanol (99%) and 35 mL of distilled water. The resulting drug solution was gradually incorporated into 45 g of the plain HPMC gel under gentle, consistent stirring to ensure homogeneity. The final formulation was transferred into amber glass containers and stored at 4 °C protected from light to preserve physicochemical stability.15,16

In vitro susceptibility of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline

The antifungal activity of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline was evaluated in vitro using 21 reference strains. The in vitro model was established according to the protocols outlined by CLSI. The antifungal activity of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline was determined using a standard broth microdilution method. A 10 mg/mL stock solution was prepared, and an initial concentration of 256 µg/mL was used in the assay. Two-fold serial dilutions were performed to obtain a range of decreasing concentrations. Each concentration was tested in triplicate, and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined as the lowest concentration that completely inhibited visible fungal growth. The MIC values from the three replicates were averaged to determine the final value.17

After preparing the inoculum and diluting the test compound, the antifungal activity of the resulting serially diluted concentrations was tested on a 96-well plate. Controls were established, and the inoculum was added to the plates and incubated with the test compound. The tests were performed in duplicate and repeated thrice over two weeks.18,19

Quantification of inflammatory markers using ELISA

Inflammation was assessed using ELISA kits. The assays employed monoclonal antibodies, enzyme-linked detection, substrate reactions, microplate reading, and quantitative cytokine measurement for reliable and precise analysis of inflammatory markers.20

Animal testing

Male BALB mice, aged 6-8 weeks, were obtained from the animal facility at King Abdulaziz University. The mice were housed under temperature-controlled conditions (23 ± 2 °C) under a 12-h light/dark cycle, with free access to food and water. A total of 32 mice were divided into four groups, each subdivided into two cages (4-5 mice per cage) to minimize aggression and ensure well-being, following National Research Council guidelines. After monitoring for 30 days, surviving or moribund mice were humanely euthanized via ketamine-xylazine overdose administered intraperitoneally, followed by cervical dislocation. The four groups were organized as follows:

- Group 1: uninfected control group (n = 8).

- Group 2: received inoculum but no additional treatment (n = 8).

- Group 3: inoculated with C. albicans ATCC 10231 and treated with 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline at 0.02 mg/mL (n = 8).15

- Group 4: inoculated with C. albicans ATCC 10231 and treated with 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline at 0.2 mg/mL (n = 8).

All animal experiments were performed in strict adherence to the animal care and use guidelines approved by King Abdulaziz University. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care at King Abdulaziz University (KAU) and complies with the CCAC guidelines.21

The animal procedures performed in this study conformed to the approved protocols established by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy at King Abdulaziz University (reference number: PH-1444-57).

Animal preparation and oral infection

Oral candidiasis was induced in mice through immunosuppression using two injections of prednisolone (100 mg/kg), administered one day before and three days after infection with C. albicans ATCC 10231. Tetracycline hydrochloride (0.9 mg/mL) was added to drinking water one day before infection. The mice were anesthetized using an intramuscular injection of chlorpromazine chloride (2 mg/mL; 50 µL per femur). Infection was established by swabbing the oral cavity with C. albicans (2.0 × 108 cells/mL) using soaked cotton pads. Infection severity was monitored daily by observing whitish, curd-like patches on the surface of the tongue.22 Decisions regarding euthanasia were made according to institutional ethical guidelines and protocols to ensure humane treatment and compliance with regulatory standards established by the Research Ethics Committee (Faculty of Pharmacy, KAU, Jeddah, SA; reference number: PH-1444-57).

Assessment of infection progression

On day 7, the primary assessment point, the mice (32 animals) were anesthetized and euthanized to evaluate tongue lesion severity. Infection was scored macroscopically (on a scale of 0 to 4) based on the extent of whitish, curd-like patches on the tongue.

Scoring criteria

- 0: Normal, uninfected tongue.

- 1: Patches covering <20% of the tongue surface.

- 2: Patches covering 20%-90% of the tongue surface.

- 3: Patches covering >90% of the tongue surface, indicating substantial infection.

- 4: Thick pseudomembranous patches on >91% of the tongue surface, indicating advanced infection.

This scoring system allowed precise infection severity assessment.15,22

Antifungal treatment

In the antifungal treatment groups, 0.5 mL of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline was administered 3 h after the initial C. albicans inoculation, and antifungal efficacy was evaluated 72 h post-infection (day 3). The treatment regimen entailed daily application of 2,3-Dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline to the oral cavity for eight consecutive days, from day 0 to day 7 post-infection. The topical agent was applied directly using a cotton swab to guarantee comprehensive coverage of the entire oral cavity, encompassing the tongue, buccal mucosa, and soft palate. For the control group, infected animals received 0.5 mL of sterile saline containing 0.8% agar daily. Negative control mice were immunosuppressed but not infected and were evaluated on day 3 to compare antifungal treatment efficacy.22

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. The experiments were repeated twice to ensure reliability. Unpaired t-tests were used to determine statistical significance (p ≤ 0.05). Results were expressed as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

In vitro efficacy of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline

The antifungal efficacy of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline was assessed in vitro using the broth microdilution method. The MIC values for the activity of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline against various C. albicans strains are shown in Table. After 24 h of incubation, the compound exhibited marked efficacy against various C. albicans strains, demonstrating greater efficacy against C. glabrata and C. krusei. Conversely, isolates of C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. auris exhibited variable susceptibility to 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline. The differences in efficacy against these Candida species indicate the potential selectivity and specificity of the compound’s antifungal activity. Supporting this, 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline did not exhibit efficacy against various Aspergillus species, further highlighting the specificity of its antifungal properties. These findings help provide a clearer understanding of the antifungal profile of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline, emphasizing its efficacy against specific Candida strains while indicating limited activity against Aspergillus species (Table).

Table:

The efficacy of 2,3-Dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline against different Candida and Aspergillus spp.

| No. of Sample | Isolate | A501 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conc. µg/ml 24 h | Conc. µg/ml 48 h | ||

| 1 | C. albicans ATCC 10231 | 16 | 32 |

| 2 | C. albicans ATCC 90028 | 32 | 64 |

| 3 | Candida albicans ATCC MYA 573 | 16 | >64 |

| 4 | Candida albicans MMX 7424 | 32 | 32 |

| 5 | Candida tropicalis ATCC 90874 | >64 | >64 |

| 6 | Candida tropicalis MMX 7525 | 8 | 16 |

| 7 | Candida glabrata ATCC 90030 | 8 | 8 |

| 8 | Candida glabrata MMX 7285 | 4 | 4 |

| 9 | Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | 16 | >64 |

| 10 | Candida krusei ATCC 6258 | 4 | 32 |

| 11 | Candida auris MMX 9867 | 32 | >64 |

| 12 | Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC MYA 3626 | >64 | >64 |

| 13 | Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 204305 | >64 | >64 |

| 14 | Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC MYA 4609 | >64 | >64 |

| 15 | Aspergillus fumigatus ATCC 32820 | >64 | >64 |

| 16 | Aspergillus niger ATCC 9508 | >64 | >64 |

| 17 | Aspergillus niger MMX 5953 | >64 | >64 |

| 18 | Aspergillus flavus ATCC 22546 | >64 | >64 |

| 19 | Aspergillus flavus ATCC 64025 | >64 | >64 |

| 20 | Aspergillus brasiliensis ATCC 16404 | >64 | >64 |

| 21 | Aspergillus terreus ATCC 3628 | >64 | >64 |

Macroscopic evaluation of oral mucosa in mice

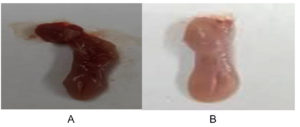

To evaluate oral candidiasis induced by C. albicans ATCC 10231, infected mice were scored based on the severity of the white patches on their tongues. Figure 1 shows the differences in infection severity between the untreated and treated groups, showing prominent lesions in infected mice, which were improved in the treated groups, underscoring the quantitative and qualitative effectiveness of the treatment.

Figure 1. Visual analysis of typical lesions, identified by white patches on the tongues of mice with oral candidiasis induced by C. albicans ATCC 10231. (A) shows the normal tongue appearance following treatment with 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline. (B) shows the presence of white patches indicative of candidiasis

In vivo anti-Candida activity of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline in a mouse oral infection model

The in vivo efficacy of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline against C. albicans ATCC 10231 was assessed using a mouse model. The results were consistent with those observed in vitro. Administering 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline at various concentrations (0.02 and 0.2 mg/mL) resulted in a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels compared to the untreated infected mice group. These findings support the potential anti-inflammatory effects of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline in vivo, indicating its capacity to modulate immune response during C. albicans infection.

Treating infected mice with 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline at concentrations of 0.02 and 0.2 mg/mL significantly reduced IL-6, IL-1β, Cox-2, iNOS, and IFN-γ levels compared to those in the untreated infected group (p < 0.05). The higher dose generally produced a more pronounced decrease, particularly in IL-6 and Cox-2 levels. Collectively, these findings indicate that 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline exerts notable anti-inflammatory effects in the infected mice (Figure 2).

Figure 2. In vivo efficacy of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline against C. albicans ATCC 10231 in a mouse model. Administering 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline at concentrations of 0.02 and 0.2 mg/mL significantly decreased (p < 0.05) the levels of various inflammatory markers compared to untreated infected mice. A) TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha, B) IL-6, C) IL-1β b, D) Cox-2, E) iNOS, and F) IFN-γ levels in the treated and untreated infected mice group. Results were expressed as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

The increasing prevalence of fungal infections has become a growing global concern. Fungal infections potentially impact millions of individuals worldwide each year, with an estimated annual death toll of approximately 1,350,000.6 The challenges associated with antimicrobial discovery, such as the significant time and effort required, are further compounded by drug resistance.23 To address this, drug repurposing, which entails the exploration of new therapeutic uses for established drugs, has emerged as a promising strategy to combat antimicrobial-resistant organisms.24 Notably, in this study, we demonstrated for the first time that 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline possesses dual activities as both an antifungal and anti-inflammatory compound, both in vitro and in vivo.

The antifungal potential of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline was evaluated against various fungal pathogens, demonstrating strong efficacy against various C. albicans strains after 24 h of incubation. Notably, it demonstrated greater efficacy against C. glabrata and C. krusei isolates. Conversely, its effectiveness against isolates of C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. auris was varied. Moreover, 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline demonstrated no efficacy against various Aspergillus species. Collectively, these findings suggest that 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline holds promise as an antifungal agent against certain fungal infections, although further evaluation is essential to validate its efficacy. The beneficial effects were evident in both the external physical appearance of the tongues as well as the overall condition of their tissues. Additionally, the restoration of the normal papillae structure within the affected tissue lesions was observed. Furthermore, we revealed that administering various doses of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline led to a notable decrease in inflammatory markers in mice. Our findings further indicate that 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline demonstrates promising potential; however, further studies are required to validate its efficacy as an antifungal agent.

Various antifungal drugs are used depending on the type of infection, its location, and the susceptibility of the causative fungal pathogen.25 However, these drugs have limitations regarding resistance, toxicity, drug interactions, and pharmacokinetic constraints, which reduce their effectiveness against various fungal infections.26 This underscores the need to develop novel agents with enhanced characteristics.27

Researchers and clinicians are continually striving to identify and develop antifungal agents with enhanced tissue penetration properties to overcome the challenges of treating deep-seated fungal infections.26,28 For example, amphotericin B is a potent antifungal agent that demonstrates promising activity in vitro; however, its clinical effectiveness for treating deep-seated fungal infections is limited. This disparity can be attributed to the suboptimal distribution of the drug within infected tissues.29 Deep-seated fungal infections require drugs that can penetrate hard-to-reach areas, such as organs or tissues with limited blood flow, and eradicate the fungi within these regions. However, as amphotericin B fails to achieve adequate concentrations within these inaccessible sites, its effectiveness is reduced in real-world clinical scenarios.29

Conversely, quinoxalines are notably characterized by their capacity to reach target tissues at therapeutically effective concentrations, in addition to favorable safety profiles.30 This suggests that quinoxalines may have the potential to overcome certain limitations encountered with other drugs, although further research is needed to substantiate this potential.

Mechanistically, 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline amplifies its antifungal capacity against various Candida species by inhibiting DNA synthesis, resulting in cell death.31 Furthermore, 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline can induce the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which disrupt cellular processes that are crucial for survival in microorganisms, leading to cell death.32 Therefore, these distinct mechanisms collectively play a key role in inducing cell death.

However, this present study had some limitations. Firstly, the lack of detailed visual and histopathological comparisons between the untreated and treated groups limited the ability to comprehensively evaluate the tissue-level impact and morphological changes following treatment. Secondly, this study did not elucidate the mechanistic basis for the differences in antifungal efficacy between Candida species or the reason for the lack of activity against Aspergillus, leaving species-specific responses unexplored. Thirdly, the absence of pharmacokinetic data limits understanding of the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline, emphasizing that the current findings are preliminary. Lastly, the potential for resistance development to 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline was not assessed, which is crucial for evaluating its long-term antimicrobial efficacy.

The present study demonstrated the effectiveness of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline against various Candida species in vitro. Assessing the in vivo effectiveness of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline is crucial, as it can offer valuable insights into its efficacy in living organisms, including pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Additionally, it is vital to investigate the potential for resistance development to determine whether various microorganisms can develop resistance to the compound over time. Future studies should also incorporate larger sample sizes, comprehensive safety evaluations, and rigorous histological and microscopic analyses to further clarify the therapeutic effects and validate the antifungal efficacy observed in this study. These investigations will help confirm these preliminary findings and establish the compound’s potential as a safe and effective antifungal therapy.

The current study demonstrated, for the first time, the remarkable efficacy of 2,3-dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline both in vivo and in vitro. This compound exhibits substantial promise as a therapeutic agent against various Candida species. However, further research and development are essential to advance this agent for clinical applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to express their sincere appreciation to the dedicated team at the Faculty of Pharmacy’s animal house, King Abdulaziz University, for their unwavering assistance in facilitating the animal-related work. Their expertise and unwavering support have played a pivotal role in enhancing the progress of our research endeavors. The authors are truly grateful for their invaluable contributions, which have greatly enriched our scientific exploration.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy at King Abdulaziz University vide reference number: PH-1444-57.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA , Andes DR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(4):e1-e50.

Crossref - Bongomin F, Gago S, Oladele RO, Denning DW. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases-estimate precision. J Fungi. 2017;3(4):57.

Crossref - Azie N, Neofytos D, Pfaller M, Meier-kriesche H, Quan SP, Horn D. The PATH (Prospective Antifungal Therapy) Alliance® registry and invasive fungal infections: Update 2012. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 201273:293-300.

Crossref - Mota Fernandes, C. et al. The Future of Antifungal Drug Therapy: Novel Compounds and Targets. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021; 65:1-13.

Crossref - Low CY, Rotstein C. Emerging fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. F1000 Med Rep. 2011;3:1-8.

Crossref - Ksiezopolska E, Gabaldon T. Evolutionary emergence of drug resistance in candida opportunistic pathogens. Genes (Basel). 2018;9(9):461.

Crossref - Jose P, Alvarez-Lerma F, Maseda E, et al. Invasive fungal infection in crtically ill patients: hurdles and next challenges. J Chemother. 2019;31(2):64-73.

Crossref - Parente-Rocha JA, Bailao AM, Amaral AC, et al. Antifungal Resistance, Metabolic Routes as Drug Targets, and New Antifungal Agents: An Overview about Endemic Dimorphic Fungi. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017(1):9870679.

Crossref - Miceli MH, Kauffman CA. Isavuconazole: A New Broad-Spectrum Triazole Antifungal Agent. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1558-1565.

Crossref - Nayak, N. Fungal infections of the eye—laboratory diagnosis and treatment. Nepal Med Coll J. 2008;10(1):48-63.

- Hutchings MI, Truman AW, Wilkinson B. Antibiotics: past, present and future. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2019;51:72-80.

Crossref - Mayer FL, Kronstad JW. Discovery of a Novel Antifungal Agent in the Pathogen Box. mSphere. 2017;2(2):e00120-17.

Crossref - Farha MA, Brown ED. Drug repurposing for antimicrobial discovery. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(4):565-577.

Crossref - Elfadil A, Ali AS, Alrabia MW, et al. The Wound Healing Potential of 2,3 Dimethylquinoxaline Hydrogel in Rat Excisional Wound Model. J Pharm Res Int. 2023;35(8):1-8.

Crossref - Alfadil A, Ibrahem KA, Alrabia MW, Mokhtar JA, Ahmed H. The fungicidal effectiveness of 2-Chloro-3-hydrazinylquinoxaline, a newly developed quinoxaline derivative, against Candida species. PLoS One. 2024;19(8):1-14.

Crossref - Khedekar YB, Mojad AA, Malsane PN. Formulation, development , and evaluation of Silymarin loaded topical gel for fungal infection. J Adv Pharm. 2019;8(1):6-9.

- Bazuhair MA, Alsieni M, Abdullah H, et al. The Combination of 3-Hydrazinoquinoxaline-2-Thiol with Thymoquinone Demonstrates Synergistic Activity Against Different Candida Strains. Infect Drug Resist. 2024;17:2289-2298.

Crossref - Tan CM, et al. Restoring Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Susceptibility to b -Lactam Antibiotics. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4.

Crossref - Mikkelsen K, Sirisarn W, Alharbi O, et al. The Novel Membrane-Associated Auxiliary Factors AuxA and AuxB Modulate b-lactam Resistance in MRSA by stabilizing Lipoteichoic Acids. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2021;57(3):106283.

Crossref - Fathy M, Nikaido T. In vivo modulation of iNOS pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma by Nigella sativa. Environ Health Prev Med. 2013;18(5):377-385.

Crossref - Halawi MH, Yassine W, Nasser R, et al. Two Weeks of Chronic Unpredictable Stress Are Sufficient To Produce Oral Candidiasis in Balb/C Mice. Asian J Microbiol Biotechnol Environ Sci. 2020;22(2):254-264.

- Takakura N, Sato Y, Ishibashi H, et al. A novel murine model of oral candidiasis with local symptoms characteristic of oral thrush. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003;47(5):321-326.

Crossref - Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, et al. Bad Bugs, No Drugs: No ESKAPE! An Update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(1):1-12.

Crossref - Boyd NK, Teng C, Frei CR. Brief Overview of Approaches and Challenges in New Antibiotic Development: A Focus On Drug Repurposing. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:1-12.

Crossref - de Oliveira Santos GC, Vasconcelos CC, Lopes AJO, et al. Candida infections and therapeutic strategies: Mechanisms of action for traditional and alternative agents. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1-23.

Crossref - Nguyen HM, Graber CJ. Limitations of antibiotic options for invasive infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: is combination therapy the answer? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;65(1):24-36.

Crossref - Ba X, Harrison EM, Lovering AL, et al. Old drugs to treat resistant bugs: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates with mecC are susceptible to a combination of penicillin and clavulanic acid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(12):7396-7404.

Crossref - Davis JS, van Hal S, Tong SYC. Combination antibiotic treatment of serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(1):3-16.

Crossref - Kloezen W, Parel F, Bruggemann R, et al. Amphotericin B and terbinafine but not the azoles prolong survival in Galleria mellonella larvae infected with Madurella mycetomatis. Med Mycol. 2018;56(4):469-478.

Crossref - Ajani OO. Present status of quinoxaline motifs: Excellent pathfinders in therapeutic medicine. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;85:688-715.

Crossref - Cheng G, Sa C, Cao C, et al. Quinoxaline 1,4-di-N-oxides: Biological activities and mechanisms of actions. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:1-21.

Crossref - Chacon-Vargas KF, Andrade-Ochoa S, Nogueda-Torres B, et al. Isopropyl quinoxaline-7-carboxylate 1,4-di-N-oxide derivatives induce regulated necrosis-like cell death on Leishmania (Leishmania) mexicana. Parasitol Res. 2018;117(1):45-58.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.