ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Escherichia coli are serious pathogens of concern responsible for intestinal and extraintestinal disorders. The presence of antibiotic-resistant pathogenic E. coli in seafood is a growing concern for food safety. This study investigated the antibiotic resistance profile of E. coli (n = 33) representing different pathogroups isolated from seafood. Pathogenic E. coli isolates from fresh seafood samples collected in Western and Southern Mumbai, India, were used for antibiotic susceptibility testing. The Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method was used for analysing the susceptibility patterns, and the results were interpreted according to the CLSI (Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute) guidelines. The multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index was determined to understand the level of antibiotic resistance. The highest resistance was observed against the third-generation cephalosporins cefotaxime (97%) and cefpodoxime (87.8%), while the least resistance was against chloramphenicol (12.1%) and Co-trimoxazole (18.2%). More than 50% of the isolates were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, aminoglycosides such as gentamicin and amikacin, imipenem, meropenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, Amoxycillin-clavulanic acid, and colistin. The highest (0.95) and the lowest (0.09) MAR indices were recorded for isolates belonging to enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) and enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) pathogroups, respectively. The high resistance to multiple drugs in various pathogroups of E. coli from seafood emphasizes the need to trace and contain the sources of resistant bacteria to ensure the safety of seafood for consumption and prevent dissemination of such strains in the seafood consumer community.

Escherichia coli, Antibiotic Resistance, Seafood, MDR, Pathogroup, Safety

The growth of antimicrobial drug resistance in bacteria is a one-health issue that poses significant health challenges to the public, impacts food security, and undermines sustainable development globally.1 The surge in the occurrence of resistant superbugs has become a global concern and has threatened the future of antimicrobial therapy.2 Recurrent misuse and overuse of antibacterial agents like antibiotics in humans and animal health has a direct influence on the emergence of drug resistance in bacterial pathogens of human health significance.3 Humans can acquire resistant enteric pathogens through various sources, such as contaminated food and water. The coastal-marine environment is readily prone to faecal contamination from human and animal wastes introduced through land runoff, sewage discharge, and various other anthropogenic activities.4 Consequently, fish and shellfish harvested from faecally contaminated waters harbour enteric pathogens. Among others, E. coli is an important bacterium from a human health perspective, found associated with fish and shellfish exposed to faecal contamination.5 Although E. coli strains are well-known common commensals residing in the digestive tract of humans and the endotherms, distinct clonal types have acquired virulence traits, making them highly pathogenic, capable of triggering various intestinal and extraintestinal infections.

The traditional indicator status of E. coli changed with the identification of pathogroups that can cause diverse infections across all age groups. E. coli indicates the existence of other enteric bacteria, viruses, and parasites, which are introduced via faecal contamination, and is also a pathogen itself capable of causing diverse infections. Based on the serovar distribution, presence of virulence genes, and the interactions with the cultured cells, pathogenic E. coli are broadly classified into five pathogroups, namely enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enterohemorrhagic (Shiga toxin-producing) E. coli (EHEC/STEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), and enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC).6

Resistance to antibiotics is increasingly being reported in food-associated E. coli. The imprudent use of antibiotics in healthcare services and agriculture is one of the key determinants contributing to the rising resistance against antibiotics in pathogenic E. coli. Food as a vehicle for resistant pathogens can have serious implications for the health of the consumer community, as well as the dissemination and evolution of resistant clones.7

Anthropogenic contamination of coastal-marine waters contributes to the incidence of enteric bacterial and viral pathogens. The level of faecal contamination, the incidence of E. coli, and their different pathogroups in fresh and processed seafood have been reported from India.8,9 However, the problem is more confounding when multidrug-resistant strains are encountered in seafood, like the extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) or the carbapenemase-producing strains.10,11 The incidence of blaNDM-harboring E. coli in wild-caught seafood from India has emphasized the need to focus on the consequences for public well-being due to seafood-originated antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The ability of E. coli to persist continuously in seawater over an extended period can contribute to its wider dissemination and exposure to horizontal gene transfer events, leading to the acquisition of Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes from the environment. E. coli contamination of seafood is a significant challenge for food safety in developing economies with strained sanitation infrastructure, owing to the large population, particularly in urban areas.12 Recently, we reported the isolation of E. coli belonging to all pathogroups (EHEC/STEC, EPEC, ETEC, EAEC, and EIEC) from fresh finfish and shellfish samples marketed in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.9 In this study, we investigated the pattern of resistance of pathogenic E. coli isolates from seafood representing distinct pathogroups towards important antibiotics. This will further help us understand the implications of such bacteria on consumer health.

Isolates of Escherichia coli

Confirmed isolates of E. coli (n = 33) used in this study were previously recovered from fresh seafood samples collected from fish landing centres, retail fish markets, and a retail supermarket, all located in Mumbai, India (Table 1).9 Among 33 E. coli isolates, 16 were isolated from finfish and 17 were from shellfish (Table 1). Of these, 23 isolates belonged to EHEC/STEC, five to ETEC, two to each of EPEC and EAEC, and one to EIEC. The EHEC isolates consisted of serotypes O120, O157, O26, O83, O149, O134, O20, O135 and O7. ETEC isolates belonged to O7, O83, and O134; EPEC isolates to O120 and O135; EAEC to O18 and O134; and EIEC to O7. The isolates were stored in glycerol broth at -80 °C till further analysis.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

The susceptibility of E. coli isolates to 21 antibiotics was studied using the disc diffusion method. The following antibiotics were tested; Cefotaxime (CTX; 30 µg), Ceftazidime (CAZ; 30 µg), Cefoxitin (CX; 30 µg), Cefpodoxime (CPD; 10 µg), Ceftriaxone (CTR; 30 µg), Cephalothin (CEP; 30 µg), Chloramphenicol (C; 30 µg), Ciprofloxacin (CIP; 5 µg), Co-Trimoxazole (COT; 25 µg), Gentamicin (GEN; 10 µg), Imipenem (IPM; 10 µg), Meropenem (MRP; 10 µg), Nalidixic acid (NA; 30 µg), Ertapenem (ETP; 10 µg), Piperacillin/Tazobactam (PIT; 100/10 µg), Aztreonam (AT; 30 µg), Amoxycillin-clavulanic acid (AMC; 30 µg), Colistin (CL; 10 µg), Amikacin (AK; 30 µg), Tetracycline (TE; 30 µg) and Trimethoprim (TR; 5 µg).

The Kirby-Bauer method was used to determine the antibiotic sensitivity of E. coli. Bacteria were grown in Mueller-Hinton (MH) medium (Hi-Media, Mumbai, India) to 0.5 McFarland turbidity unit. The broth culture was inoculated onto a Mueller-Hinton agar plate by spreading it uniformly on the agar with a sterile swab. After drying the plates for 5 minutes, the antibiotic discs were placed on the agar surface using sterile forceps. After incubation at 37 °C for 18 hours, the diameter of the zones of inhibition was measured. Interpretations as susceptible, intermediate and resistant were made as per the guidelines of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).13

Multiple Antibiotic Resistance (MAR) index

The level of resistance against antibiotics was calculated employing the formula,

MAR index = a/b,

where

a is the number of antibiotics to which the bacterium is resistant, and b is the total number of antibiotics tested.14

Susceptibility patterns of isolates of pathogenic E. coli against antibiotics

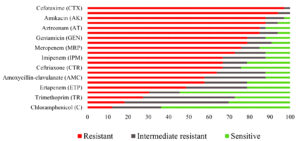

Table 1 presents the details of E. coli isolates used in this study, including their pathogroup affiliations, serogroups, and the source of isolation. The majority of the isolates screened belonged to the EHEC pathogroup, followed by ETEC, EPEC, EAEC, and EIEC. The serogroup O120 was the most prevalent serogroup among EHEC isolates, and O7 was the most prevalent among ETEC isolates. The susceptibility patterns of pathogenic E. coli isolates against selected antibiotics are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. Third-generation cephalosporin resistance was found to be common in the tested isolates, with 32 out of 33 (97%) isolates being resistant to one or more cephalosporins. The highest resistance was against cefotaxime (97%), followed by cefpodoxime (87.8%), ceftazidime (78.8%), ceftriaxone (66.7%), cephalothin (63.6%), and cefoxitin (57.6%).

Table (1):

Escherichia coli isolates used in this study, their pathogroup affiliations, serogroups and the source of isolation

No. |

Isolate |

Pathogroup |

Serogroup |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

PSE64 |

EHEC |

O120 |

Parapenaeopsis stylifera |

2 |

PMH55 |

EHEC |

O157 |

Penaeus monodon |

3 |

MPH7 |

EHEC |

026 |

Polydactylus heptadactylus |

4 |

LSHM6 |

EHEC |

083 |

Harpadon nehereus |

5 |

4SBD12 |

EAEC |

O18 |

Harpadon nehereus |

6 |

TIS71 |

EHEC |

O120 |

Parapenaeopsis stylifera |

7 |

TIE83 |

ETEC |

07 |

Parapenaeopsis stylifera |

8 |

CRS10 |

EIEC |

07 |

Metapenaeus affinis |

9 |

HNE10 |

EHEC |

083 |

Harpadon nehereus |

10 |

NET87 |

EHEC |

O149 |

Odontamblyopus roseus |

11 |

4MSH40 |

EHEC |

O134 |

Parapenaeopsis stylifera |

12 |

DHS39 |

ETEC |

07 |

Johnius macrorhynus |

13 |

TMOT1 |

EHEC |

O20 |

Opisthopterus tardoore |

14 |

TEC19 |

ETEC |

O83 |

Meretrix casta |

15 |

TMSA2 |

EHEC |

O157 |

Opisthopterus tardoore |

16 |

SC2 |

EHEC |

083 |

Harpadon nehereus |

17 |

PSM65 |

EHEC |

O120 |

Parapenaeopsis stylifera |

18 |

BDS6 |

ETEC |

O7 |

Harpadon nehereus |

19 |

BD651 |

EHEC |

O83 |

Harpadon nehereus |

20 |

TMA7 |

ETEC |

O134 |

Fenneropenaeus indicus |

21 |

MLV17 |

EHEC |

O135 |

Metapenaeopsis stridulans |

22 |

LSBD21 |

EHEC |

O120 |

Harpadon nehereus |

23 |

MAM8 |

EHEC |

O135 |

Megalaspis cordyla |

24 |

BDE6 |

EHEC |

O120 |

Harpadon nehereus |

25 |

4MSH38 |

EHEC |

O135 |

Parapenaeopsis stylifera |

26 |

MLV18 |

EHEC |

O134 |

Metapenaeopsis stridulans |

27 |

4SSH61 |

EHEC |

O135 |

Parapenaeopsis stylifera |

28 |

TIM651 |

EPEC |

O120 |

Parapenaeopsis stylifera |

29 |

TSOT13 |

EHEC |

O134 |

Opisthopterus tardoore |

30 |

TECL3 |

EHEC |

O7 |

Meretrix casta |

31 |

LEBD13 |

EAEC |

O134 |

Harpadon nehereus |

32 |

PMM31 |

EHEC |

O157 |

Penaeus monodon |

33 |

PMH14 |

EPEC |

O135 |

Penaeus monodon |

Table (2):

Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of E. coli isolates

Antibiotics used |

No. (%) resistant |

No. (%) intermediate resistant |

No. (%) sensitive |

|---|---|---|---|

Cefotaxime (CTX) |

32 (97) |

1 (3) |

0 |

Ceftazidime (CAZ) |

26 (78.8) |

4 (12.1) |

3 (9.1) |

Cefoxitin (CX) |

19 (57.6) |

7 (21.2) |

7 (21.2) |

Cefpodoxime (CPD) |

29 (87.8) |

2 (6.1) |

2 (6.1) |

Ceftriaxone (CTR) |

22 (66.7) |

3 (9.1) |

8 (24.2) |

Cephalothin (CEP) |

21 (63.6) |

8 (24.2) |

4 (12.1) |

Chloramphenicol (C) |

4 (12.1) |

8 (24.2) |

21 (63.6) |

Ciprofloxacin (CIP) |

22 (66.7) |

4 (12.1) |

7 (21.2) |

Co-Trimoxazole (COT) |

6 (18.2) |

17 (51.5) |

10 (30.3) |

Gentamicin (GEN) |

26 (78.8) |

3 (9.1) |

4 (12.1) |

Imipenem (IPM) |

22 (66.7) |

7 (21.2) |

4 (12.1) |

Meropenem (MRP) |

25 (75.8) |

3 (9.1) |

5 (15.1) |

Nalidixic Acid (NA) |

24 (72.7) |

5 (15.2) |

4 (12.1) |

Ertapenem (ETP) |

16 (48.5) |

10 (30.3) |

7 (21.2) |

Piperacillin/Tazobactam (PIT) |

28 (84.8) |

3 (9.1) |

2 (6.1) |

Aztreonam (AT) |

28 (84.9) |

1 (3.0) |

4 (12.1) |

Amoxycillin-clavulanate (AMC) |

19 (57.6) |

10 (30.3) |

4 (12.1) |

Colistin (CL) |

31 (93.9) |

2 (6.1) |

0 |

Amikacin (AK) |

29 (87.9) |

3 (9.1) |

1 (3.0) |

Tetracycline (TE) |

10 (30.3) |

5 (15.2) |

18 (54.5) |

Trimethoprim (TR) |

9 (27.3) |

15 (45.4) |

9 (27.3) |

Further, 28 (84.9%) isolates were resistant to aztreonam, 25 (75.8%) to meropenem, 22 (66.7%) to imipenem, and 16 (48.5%) were resistant to ertapenem. A high level of resistance was noted against quinolone antibiotics, with 24 (72.7%) isolates being resistant to nalidixic acid and 22 (66.7%) isolates being resistant to ciprofloxacin. The aminoglycoside resistance was also significant. Twenty-nine (87.9%) and 26 (78.8%) isolates were resistant to amikacin and gentamicin, respectively. Thirty-one (93.9%) isolates were resistant to colistin.

Among other antibiotics, 28 (84.8%) exhibited resistance to piperacillin/tazobactam, and 19 (57.6%) were resistant to the amoxycillin-clavulanate antibiotic-inhibitor combination. The isolates were relatively more susceptible to co-trimoxazole, tetracycline, trimethoprim, and chloramphenicol antibiotics, with 6 (18.2%), 10 (30.3%), 9 (27.3%), and 4 (12.1%) isolates, respectively exhibiting resistance to these antibiotics.

None of the isolates were sensitive to cefotaxime and colistin. A very few isolates showed sensitivity towards amikacin (1, 3.0%), cefpodoxime (2, 6.1%), and piperacillin/ Tazobactam (2, 6.1%), indicating a high level of resistance of the tested isolates towards these antibiotics. A relatively high level of sensitivity was noted against tetracycline (18, 54.5%) and chloramphenicol (21, 63.6%), where the number of sensitive isolates exceeded that of resistant and intermediate-resistant isolates. However, in the case of co-trimoxazole and trimethoprim, the number of intermediate-resistant isolates exceeded that of resistant and sensitive isolates, at 17 (51.5%) and 15 (45.4%), respectively.

Multiple drug resistance profiles of E. coli isolates and the MAR index

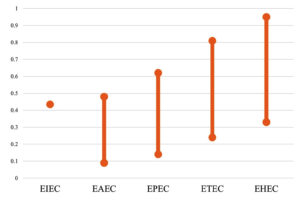

Most of the tested isolates displayed multiple drug resistance (MDR) phenotypes. The MAR index of the tested E. coli ranged from 0.09 to 0.95 (Table 3 and Figure 2). Two isolates, PSE64 and TSOT13, belonging to the EHEC pathogroup, had a MAR index of 0.95. On the contrary, isolate LEBD13, which belonged to EAEC, showed the least resistance (two antibiotics), with a MAR index of 0.09. Two other isolates, PMH14 (EPEC) and TEC19 (ETEC), exhibited resistance to three and five antibiotics, respectively, with minimum MAR indices of 0.14 and 0.24 (Table 3). TIS71, MLV17, LSBD21, and BDE6, belonging to the EHEC pathogroup, exhibited a high level of resistance, with each having an MAR index of 0.9. All isolates of EHEC O120 serogroup, the most prevalent among others, had a comparatively high MAR index, ranging from 0.76 to 0.95 (Table 3).

Table (3):

Multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) indices of the isolates

Isolate |

Patho-group |

Sero-group |

Number of antibiotics to which resistant |

MAR index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

PSE64 |

EHEC |

O120 |

20 |

0.95 |

TSOT13 |

EHEC |

O134 |

20 |

0.95 |

TIS71 |

EHEC |

O120 |

19 |

0.9 |

MLV17 |

EHEC |

O135 |

19 |

0.9 |

LSBD21 |

EHEC |

O120 |

19 |

0.9 |

BDE6 |

EHEC |

O120 |

19 |

0.9 |

PMH55 |

EHEC |

O157 |

18 |

0.86 |

4MSH38 |

EHEC |

O135 |

18 |

0.86 |

TIE83 |

ETEC |

O7 |

17 |

0.81 |

4MSH40 |

EHEC |

O134 |

17 |

0.81 |

TMSA2 |

EHEC |

O157 |

17 |

0.81 |

TECL3 |

EHEC |

O7 |

17 |

0.81 |

MPH7 |

EHEC |

O26 |

16 |

0.76 |

SC2 |

EHEC |

O83 |

16 |

0.76 |

PSM65 |

EHEC |

O120 |

16 |

0.76 |

TMA7 |

ETEC |

O134 |

15 |

0.71 |

MLV18 |

EHEC |

O134 |

15 |

0.71 |

LSHM6 |

EHEC |

O83 |

13 |

0.62 |

BD651 |

EHEC |

O83 |

13 |

0.62 |

4SSH61 |

EHEC |

O135 |

13 |

0.62 |

TIM651 |

EPEC |

O120 |

13 |

0.62 |

HNE10 |

EHEC |

O83 |

12 |

0.57 |

NET87 |

EHEC |

O149 |

12 |

0.57 |

BDS6 |

ETEC |

O7 |

12 |

0.57 |

4SBD12 |

EAEC |

O18 |

10 |

0.48 |

CRS10 |

EIEC |

O7 |

9 |

0.43 |

DHS39 |

ETEC |

O7 |

9 |

0.43 |

TMOT1 |

EHEC |

O20 |

9 |

0.43 |

MAM8 |

EHEC |

O135 |

8 |

0.38 |

PMM31 |

EHEC |

O157 |

7 |

0.33 |

TEC19 |

ETEC |

O83 |

5 |

0.24 |

PMH14 |

EPEC |

O135 |

3 |

0.14 |

LEBD13 |

EAEC |

O134 |

2 |

0.09 |

The one isolate representing the EIEC pathogroup (CRS10) showed resistance to 9 out of 21 antibiotics, with an MAR index of 0.43 (Table 3 and Figure 2). The two EAEC isolates (4SBD12 and LEBD13) exhibited a difference of 0.39 in value. The range of MAR index obtained for the five ETEC and two EPEC isolates tested varied from low to high, with values of 0.24 to 0.81 and 0.14 to 0.62, respectively. Fifteen out of 23 (65.2%) EHEC isolates had a MAR index above the average MAR index of 0.65. Overall, the MAR index range of isolates belonging to the EHEC pathogroup ranged between 0.33 and 0.95, and the least MAR index was noted for the isolate PMM31 (0.33). All three EHEC O157 isolates, PMH55, TMSA2, and PMM31, tested in this study showed a varied MAR index of 0.86, 0.81, and 0.33, respectively. These were isolated from shrimp (Penaeus monodon) and fish (Opisthopterus tardoore) samples.

Of 23 EHEC isolates tested in this study, two were resistant to 20 antibiotics, 4 to 19, 2 to 18, 3 to 17, 3 to 16, 1 to 15, 3 to 13, 2 to 12, and one each to 9, 8, and 7 antibiotics (Table 3). Multidrug-resistance patterns of EHEC isolates are shown in Figure 3. All the EHEC isolates tested showed resistance to colistin, and 21 isolates each exhibited resistance to aminoglycosides, monobactams, and amoxycillin-clavulanate. Five isolates were resistant to phenicol (Figure 3). Five ETEC isolates were tested, with one isolate each being resistant to 17, 15, 12, 9, and 5 antibiotics. Five isolates, three of which belonged to the O7 serotype and one each to O83 and O134, exhibited varying drug resistance patterns, with their MAR indices ranging from 0.24 to 0.81 (Figure 3). All the isolates were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (Figure 3).

Two EPEC isolates tested were resistant to 13 and three antibiotics, respectively, while two isolates of EAEC were resistant to 10 and two antibiotics. Two EPEC isolates differed significantly in terms of antimicrobial resistance, with isolate TIM651 exhibiting resistance to 13 antibiotics, including cephalosporins, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, β-lactam/ inhibitor combinations, aztreonam, and colistin. In contrast, isolate PMH14 was resistant to only three antibiotics: cefotaxime, aztreonam, and colistin (Table 4). A similar trend was observed in EAEC isolates also.

Table (4):

Antibiotic resistance profiles of E. coli isolates exhibiting multidrug-resistance (MDR) phenotypes

Isolate |

No. of antibiotics to which resistant |

Resistance profile |

|---|---|---|

PSE64 |

20 |

CAZ, CTR, CTX, CX, CPD, CEP, GEN, CIP, COT, NA, IPM, MRP, ETP, PIT, AT, AMC, CL, AK, TE, TR |

TSOT13 |

20 |

CAZ, CTR CTX, CX, CEP, CPD, CIP, GEN, COT, IPM, MRP, ETP, NA, PIT, AT, AMC, CL, AK, TE, TR |

MLV17 |

19 |

CAZ, CTX, CX, CTR, CPD, CEP, GEN, COT, MRP, CIP, NA, PIT, ETP, AT, AMC, C, CL, AK, TE |

TIS71 |

19 |

CTX, CTR, CAZ, CX, CPD, CEP, CIP, GEN, COT, IPM, MRP, ETP, PIT, AT, NA, AMC, CL, AK, TR |

LSBD21 |

19 |

CAZ, CTR, CTX, CX, CPD, CEP, CIP, COT, GEN, MRP, NA, ETP, PIT, AMC, C, CL, AK, TE, TR |

BDE6 |

19 |

CAZ, CTR, CX, CTX, CPD, GEN, CEP, CIP, IPM, MRP, NA, ETP, PIT, AT, AMC, C, CL, AK, TE |

PMH55 |

18 |

CAZ, CTX, CPD, CX, CEP, GEN, MRP, IPM, CIP, NA, PIT, AT, ETP, C, CL, AK, TE, TR |

4MSH38 |

18 |

CAZ, CTX, CX, CTR, CPD, GEN, CEP, CIP, IPM, MRP, NA, ETP, PIT, AT, AMC, CL, AK, TE |

TIE83 |

17 |

CTX, CTR, CAZ, CX, CEP, GEN, CIP, IPM, COT, PIT, AT, NA AMC, CL, AK, TE, TR |

4MSH40 |

17 |

CTX, CTR, CAZ, CX, CPD, CEP, GEN, CIP, IPM, MRP, NA, ETP, PIT, AT, AMC, CL, AK |

TMSA2 |

17 |

CAZ, CTX, CX, CTR, CPD, CEP, GEN, CIP, IPM, MRP, NA, ETP, PIT, AT, AMC, CL, AK |

TECL3 |

17 |

CAZ, CTX, CX, CTR, CPD, CEP, CIP, IPM, MRP, GEN, NA, ETP, PIT, AT, AMC, CL, AK |

MPH7 |

16 |

CTX, CX, CAZ, CTR, CPD, CEP, IPM, MRP, GEN, CIP, NA, PIT, AT, AMC, CL, AK |

SC2 |

16 |

CAZ, CTX, CX, CTR, CPD, CEP, GEN, CIP, IPM, MRP, NA, ETP, PIT, AT, CL, AK |

PSM65 |

16 |

CAZ, CTX, CX, CTR, CPD, GEN, CEP, CIP, IPM, MRP, ETP, PIT, AT, AMC, CL, AK |

TMA7 |

15 |

CAZ, CTX, CX, CTR, CPD, GEN, CEP, CIP, IPM, MRP, ETP, PIT, AT, CL, AK |

MLV18 |

15 |

CTX, CAZ, CX, CPD, CTR, CEP, GEN, IPM, MRP, NA, PIT, AT, AMC, CL, TR |

LSHM6 |

13 |

CTX, CPD, CAZ, CIP, GEN, COT, MRP, PIT, NA, AT, AMC, CL, AK |

BD651 |

13 |

CAZ, CTX, CTR, CX, CEP, CIP, CPD, NA, GEN, AT, AMC, C, CL |

4SSH61 |

13 |

CTX, CPD, CAZ, CTR, GEN, IPM, NA, MRP, PIT, ETP, AT, CL, AK |

TIM651 |

13 |

CAZ, CTX, CEP, GEN, CPD, MRP, IPM, PIT, ETP, AT, AMC, CL, AK |

HNE10 |

12 |

CTX, CPD, CIP, GEN, IPM, MRP, NA, PIT, AT, AMC, CL, AK |

NET87 |

12 |

CAZ, CTX, CIP, CPD, GEN, PIT, MRP, NA, AT, AMC, CL, AK |

BDS6 |

12 |

CTX, CAZ, CX, CPD, CEP, MRP, NA, ETP, PIT, AMC, C, CL |

4SBD12 |

10 |

CTX, CPD, CIP, GEN, NA, PIT, AT, CL, AK, TR |

CRS10 |

9 |

CTX, CAZ, CPD, CIP, GEN, MRP, NA, CL, AK |

DHS39 |

9 |

CTX, CAZ, CPD, CTR, CEP, NA, PIT, AK, TE |

TMOT1 |

9 |

CTX, CAZ, CPD, CTR, CEP, NA, PIT, AT, CL |

MAM8 |

8 |

CTX, CPD, CTR, MRP, PIT, AT, CL, AK |

PMM31 |

7 |

CTX, COT, GEN, CL, AK, TE, TR |

TEC19 |

5 |

CTX, CX, CPD, MRP, AK |

PMH14 |

3 |

CTX, AT, CL |

LEBD13 |

2 |

CL, AK |

The least resistance was observed in an isolate of EAEC (LEBD13), which was resistant to only two antibiotics, colistin and amikacin (Table 4). This isolate was recovered from a sample of Bombay duck fish (Harpadon nehereus) and belonged to the serotype O134. The second EAEC (4SBD12) isolate of this study was resistant to 10 antibiotics (Table 4). The isolate was sensitive to carbapenems, some cephalosporins, amoxicillin-clavulanate, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, etc. Both the EAEC isolates were resistant to colistin and the aminoglycoside antibiotic amikacin. In contrast, both the EPEC isolates showed resistance to third-generation cephalosporins in addition to these antibiotics (Figure 3). A single isolate of EIEC (CRS10) from shrimp was susceptible to multiple cephalosporins, as well as some carbapenems, including imipenem and ertapenem, amoxicillin-clavulanate, piperacillin-tazobactam, and tetracycline (Table 4).

Addressing antibiotic resistance has become an international focus as it affects humans, animals, and agricultural systems. In this investigation, E. coli isolates representing different pathogroups recovered from seafood samples collected from Mumbai were examined for their susceptibility to antimicrobials. Considering the persistent contamination of coastal waters in this densely populated metropolitan city, we anticipated an increased incidence of antibiotic-resistant E. coli.

The results of antibiotic susceptibility testing indicated the occurrence of E. coli pathogroups resistant to most clinically relevant antibiotics. The result is alarming, as E. coli in general is intrinsically susceptible to nearly all the antimicrobial agents of clinical significance.15 However, E. coli is known for its receptive capacity to accumulate resistant genes, especially through horizontal gene transfer; this might have played an important role in its evolution with respect to antimicrobial resistance and its rapid spread among pathogroups.5,16 For the last decades, the number of resistance genes in E. coli has been steadily increasing, which has made E. coli a bacterium with the highest burden of antibiotic resistance.17,18

Resistance to third-generation cephalosporins was prevalent (97%) among the pathogenic isolates (Table 2, Figure 1). We observed the highest resistance against cefotaxime (97%) and the lowest resistance against ceftriaxone (66.7%) in our E. coli isolates. Singh et al. reported a similar level of resistance in Enterobacterales isolated from seafood in Mumbai, where a majority (>90%) of the tested isolates showed resistance to cefotaxime, cefpodoxime, and ceftazidime, which are third-generation cephalosporins.11 The percentage of resistance shown by the isolates towards cefotaxime (95%) was high and comparable to our results. High cephalosporin resistance in E. coli isolates from frozen shrimp has been reported from Saudi Arabia.19 However, this study reported high resistance towards first-generation cephalosporins compared to resistance to third-generation cephalosporins observed in our study. Our study also showed high resistance to aminoglycosides, monobactams, carbapenems, quinolones, and fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Ibrahim and Elhadi reported a different susceptibility pattern for penicillin (ampicillin 90.7%, piperacillin 87.1%), quinolones (nalidixic acid 64.2%), sulfonamides (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 50.7%), and tetracycline (41.4%).19 Contrary to our findings, a study from China reported high resistance of E. coli isolates isolated from fish and shellfish towards chloramphenicol (72.1%) and tetracycline (93.7%).20 E. coli isolated from fish samples in Cameroon, Africa, showed high resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ampicillin, and ticarcillin compared to other antibiotics.21 Notably, different resistance patterns are usually observed for pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains of E. coli owing to the presence of resistant genes on plasmids. In addition to several plasmid-borne antibiotic resistance genes, E. coli possesses the marRAB locus. This chromosomally encoded intrinsic resistance mechanism confers resistance to various antibiotics, including tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, cephalosporins, nalidixic acid, penicillins, rifampin, and fluoroquinolones.22 Overall, the isolates screened in this present study were largely resistant towards beta-lactam antibiotics, and relatively more sensitive to non-beta-lactam antibiotics. Resistance towards beta-lactam antibiotics is common among bacteria, and its emergence is on the rise due to their widespread use.23

Among 23 EHEC isolates tested, a large proportion of EHEC/STEC isolates were resistant to 7-20 antibiotics with their MAR indices ranging from 0.33-0.95 (Tables 3 and 4). Some of these included the well-known EHEC serogroups O157 and O26 involved in several food-borne outbreaks. EHEC O26 is an important non-O157 serogroup along with O103, O111, and O145 recognized as emerging, virulent non-O157 EHEC capable of causing bloody diarrhoea and haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS).24 Other STEC serogroup such as O7, O20, O149 (Table 3) have been reported to be associated with cattle, which are the major reservoirs of STEC strains.25,26 Three isolates of EHEC O157, isolated from different seafood samples, were resistant to 7, 17, and 18 antibiotics, respectively (Table 3). The isolation of serogroup O157 resistant to only ciprofloxacin from fish was reported by Onmaz et al. in 2020.27 Two EHEC/STEC isolates were resistant to each antibiotic tested except chloramphenicol. Overall, the tested EHEC isolates showed high resistance towards colistin, aminoglycosides, and lactamase inhibitor (Figure 3). A recent study characterizing STEC isolated from shellfish in Egypt reported resistance to multiple antibiotics, including β-lactams and β-lactam inhibitors, ciprofloxacin, colistin, tetracycline, and fosfomycin.28

Surprisingly, in our study, two EPEC isolates exhibited markedly different resistance profiles. The isolate TIM651 was resistant to 13 antibiotics, while PMH14 was resistant to only three antibiotics (Table 4). Even though many EPEC isolates share similar antibiotic resistance profiles, variations can be expected, as these pathogenic strains are highly diverse in nature.29 Both the isolates showed resistance towards third-generation cephalosporins, monobactam, and colistin (Figure 3). Studies from India suggest that EPEC clinical strains have gained resistance to multiple antibiotics commonly employed in the treatment of diarrheal diseases.30,31 A study reported total resistance to cephalothin, cefuroxime, and sulfamethoxazole, as well as very high resistance to tetracycline (76.3%) and streptomycin (84.2%) in clinical EPEC isolates.29 In our isolates, tetracycline resistance was not found, and also, only one isolate showed resistance to cephalothin.

Varying antibiotic resistance patterns were observed among the ETEC isolates. The isolate TIE83 with a MAR index of 0.81 was sensitive to cefpodoxime, chloramphenicol, ertapenem, and meropenem, and was resistant to all other 17 antibiotics, including third-generation cephalosporins (Table 4 and Figure 3). In contrast, the isolate TEC19 was resistant to five antibiotics, including cefotaxime, cefoxitin, cefpodoxime, meropenem, and amikacin. Two isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin in addition to cephalosporins and carbapenems. Since the emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant ETEC in 2001, there has been a trend of increasing resistance patterns of ETEC to fluoroquinolones.32,33 High prevalence of resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ampicillin, and tetracycline was seen among the ETEC isolates obtained from ready-to-eat foods in China.20 This study reports tetracycline resistance as 66.7%, whereas we found 40% resistance against tetracycline. Among 33 isolates screened, 32 isolates showed multidrug-resistance. Studies on the prevalence of seafood-originated drug-resistant E. coli from samples collected from Southern India reported the occurrence of strains with multiple drug resistance, implicating seafood as the carrier of MDR bacteria.34,35 According to a new investigation on the occurrence of ESBL-producing bacteria in seafood, 169 (78.60%) isolates of different Enterobacterales species showed an ESBL-positive phenotype, with E. coli representing the major species.36 Various ESBL-encoding genes were also identified in these isolates. Further, the occurrence of blaNDM-harboring E. coli has also been reported in seafood.10,36 A few other studies have reported the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant E. coli in commercial seafood samples in Korea,37,38 commercial fish captured from Conception Bay, Chile,39 shellfish from retail markets of Vietnam,40 shrimps and shrimp farm environments in Thailand,41 in oysters and mussels in Atlantic Canada,42 and fish from retail markets of Cambodia.43 A study from Mizoram, Northeast India, reported high prevalence of multidrug-resistant E. coli isolates belonging to EPEC and EIEC pathotypes associated with paediatric diarrhoea.30 The MDR phenotype was observed in 41.4% of the isolates, which showed high resistance against cephalosporin drugs, aminoglycosides, carbapenem, fluoroquinolone, and sulphonamides. Multidrug-resistance involving β-lactams, third-generation cephalosporins, piperacillin, levofloxacin, and gentamicin has been described in E. coli pathogroups isolated from diarrheic children in Bihar, India.44 Recently, Ghosh et al. reported a high incidence of diarrheagenic E. coli resistant to a minimum of six different classes of antimicrobials.45 The endemicity of different pathogroups of E. coli means that they could be found in the environment and consequently in foods, including seafood, when the sanitation infrastructure is inadequately disproportional to the population, particularly in developing nations.46 All these studies highlight the exposure of seafood to highly antibiotic-resistant E. coli from diverse sources, including humans and animals, and the need to identify contaminated sources and contain the spread of MDR pathogens via seafood.

An interesting observation from this study was the increased sensitivity to antibiotics such as chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole, and tetracycline (Figure 1). The clinical application of these antibiotics has declined significantly over the last three decades due to the development of widespread bacterial resistance.47-49 The increased susceptibility of diarrheagenic E. coli observed in this study warrants further investigation to understand the factors that have contributed to the susceptibility of E. coli to these antibiotics, particularly in light of the drastic rise in resistance to other antibiotics, such as β-lactams, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones.

The MAR indices of 33 isolates ranged from 0.09 to 0.95 (Table 3), suggesting that these strains were from a high-risk environment where they were exposed to higher levels of antibiotics due to extensive use. A similar range of MAR index, extending to 1.0 from 0.09, was also reported from the same location in seafood samples.11 The antibiotic resistance patterns of seafood isolates of this study are comparable with clinical isolates of pathogenic E. coli. The multidrug-resistance traits reported in clinical isolates of diarrheagenic E. coli in India suggest that these strains have a human reservoir, and enter the aquatic environment through various routes of contamination.

This study reports a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance, as well as multidrug-resistance, among pathogenic E. coli isolated from seafood samples. A higher MAR index indicates that these isolates originated from high-risk environments with antibiotic contamination. The presence of extremely resistant pathogenic strains compromises the safety of seafood for consumption. With the rise of extremely drug-resistant clonal strains of E. coli that can spread rapidly in the community, causing significant morbidity and mortality, their presence in seafood will further complicate control measures. The aquatic environment is a hotspot for horizontal gene transfer events that can lead to the emergence of extremely antibiotic-resistant strains. In this context, to mitigate the selective pressure from antibiotics, scientific measures under the “One Health concept” are needed to reduce imprudent antibiotic use and to treat wastewater, thereby containing the dissemination of virulent and antimicrobial-resistant E. coli through seafood.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Director, ICAR-CIFE, Mumbai, and the Director, ICAR-CIARI, Andaman and Nicobar Islands and ICAR-CIFT, Kochi, for their help and support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

ML and SHK conceptualized the study. ML, SHK and BBN collected resources. SHK applied methodology. BBN and SHK supervised the study.SP performed data collection, investigation and formal analysis. JS and ML performed data analysis.BBN performed data validation. SP wrote the manuscript. JS and ML reviewed the manuscript. JS, ML, BBN and SHK edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

This study was supported by ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Education, Mumbai, India, vide grant number CIFE-2012/9.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Kumar S, Lekshmi M, Parvathi A, Nayak BB, Varela MF. Antibiotic resistance in seafood-borne pathogens. In: Singh OV. Foodborne pathogens and antibiotic resistance. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 2016;397-415.

Crossref - Hernando-Amado S, Coque TM, Baquero F, Martinez JL. Antibiotic Resistance: Moving from Individual Health Norms to Social Norms in One Health and Global Health. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1914.

Crossref - Lekshmi M, Ammini P, Kumar S, Varela MF. The food production environment and the development of antimicrobial resistance in human pathogens of animal origin. Microorganisms. 2017;5(1):11.

Crossref - Kraemer SA, Ramachandran A, Perron GG. Antibiotic Pollution in the Environment: From Microbial Ecology to Public Policy. Microorganisms. 2019;7(6):180.

Crossref - Rocha RDS, Leite LO, de Sousa OV, Vieira RHSDF. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Escherichia coli Isolated from Fresh-Marketed Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). J Pathog. 2014;2014(1):756539.

Crossref - Gomes TAT, Elias WP, Scaletsky ICA, et al. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Braz J Microbiol. 2016;47(1):3-30.

Crossref - Canica M, Manageiro V, Abriouel H, Moran-Gilad J, Franz CMAP. Antibiotic resistance in foodborne bacteria. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019;84:41-44.

Crossref - Kumar HS, Parvathi A, Karunasagar I, Karunasagar I. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli in tropical seafood. World J Microb Biot. 2005;21(5):619-623.

Crossref - Prakasan S, Lekshmi M, Ammini P, Balange AK, Nayak BB, Kumar SH. Occurrence, pathogroup distribution and virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli from fresh seafood. Food Control. 2022;133:108669.

Crossref - Das UN, Singh AS, Lekshmi M, Nayak BB, Kumar S. Characterization of blaNDM-harboring, multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from seafood. ESPR. 2019;26(3):2455-2463.

Crossref - Singh AS, Nayak BB, Kumar SH. High Prevalence of Multiple Antibiotic-Resistant, Extended-Spectrum b-Lactamase (ESBL)-Producing Escherichia coli in Fresh Seafood Sold in Retail Markets of Mumbai, India. Vet Sci. 2020;7(2):46.

Crossref - Cui Q, Huang Y, Wang H, Fang T. Diversity and abundance of bacterial pathogens in urban rivers impacted by domestic sewage. Environ Pollut. 2019;249:24-35.

Crossref - CLSI (Clinical &Laboratory Standards Institute). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 28th ed. CLSI supplement M100, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute- Wayne, PA. 2018 clsi.org/media/1930/m100ed28_sample.pdf

- Krumperman PH. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46(1):165-170.

Crossref - Laurent P, Madec J-Y, Lupo A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli. Microbiol spectr. 2018;6(4):10-1128.

Crossref - Sun D. Pull in and push out: mechanisms of horizontal gene transfer in bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2154.

Crossref - Puvaea N, de Llanos Frutos R. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans and pet animals. Antibiotics. 2021;10(1):69.

Crossref - Marin J, Clermont O, Royer G, et al. The population genomics of increased virulence and antibiotic resistance in human commensal Escherichia coli over 30 years in France. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2022;88(15):e00664-22.

Crossref - Alhabib I, Elhadi N. Antimicrobial resistance pattern of Escherichia coli isolated from imported frozen shrimp in Saudi Arabia. PeerJ. 2024;12:e18689.

Crossref - Shuhong Z, Wu Q, Zhang J, Lai Z, Zhu X. Prevalence, genetic diversity, and antibiotic resistance of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in retail ready-to-eat foods in China. Food Control. 2016;68:236-243.

Crossref - Moffo F, Ndebe MMF, Dah I, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus spp. isolated from locally produced fish and imported fish sold in the Centre Region of Cameroon. J Food Prot. 2024;87(12):100377.

Crossref - Alekshun MN, Levy SB. Regulation of chromosomally mediated multiple antibiotic resistance:the mar regulon. AAC. 1997;41(10):2067-2075.

Crossref - Harris PNA, Tambyah PA, Paterson DL. b-lactam and b-lactamase inhibitor combinations in the treatment of extended spectrum b-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae: time for a reappraisal in the era of few antibiotic options? Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(4):475-485.

Crossref - Eichhorn I, Heidemanns K, Semmler T, et al. Highly Virulent Non-O157 Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) Serotypes Reflect Similar Phylogenetic Lineages, Providing New Insights into the Evolution of EHEC. AEM. 2015:81(20):7041-7047.

Crossref - Blanco M, Blanco JE, Mora A, et al. Serotypes, Virulence Genes, and Intimin Types of Shiga Toxin (Verotoxin)-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates from Cattle in Spain and Identification of a New Intimin Variant Gene (eae-x). J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42 (2):645-651.

Crossref - Ballem A, Goncalves S, Garcia-Menino I, et al. Prevalence and serotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in dairy cattle from Northern Portugal. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0244713.

Crossref - Onmaz NE, Yildirim Y, Karadal F, et al. Escherichia coli O157 in fish:Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, biofilm formation capacity, and molecular characterization. Lwt. 2020;133:109940.

Crossref - Al Qabili DMA, Aboueisha AKM, Ibrahim GA, Youssef AI, El-Mahallawy HS. Virulence and antimicrobial-resistance of shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) Isolated from edible shellfish and its public health significance. Arch Microbiol. 2022;204 (8):510.

Crossref - Keng FW, Radu S, Kqueen CY, et al. Antibiotic resistance, plasmid profile and RAPD-PCR analysis of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) clinical isolates. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2003;34(3):620-626.

- Chellapandi K, Dutta TK, Sharma I, De Mandal S, Kumar NS, Ralte L. Prevalence of multi drug resistant enteropathogenic and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli isolated from children with and without diarrhea in Northeast Indian population. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2017;16(1):1-9.

Crossref - Thakur N, Jain S, Changotra H, et al. Molecular characterization of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli pathotypes: Association of virulent genes, serogroups, and antibiotic resistance among moderate-to-severe diarrhea patients. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018:32 (5):22388.

Crossref - Chakraborty S, Deokule JS, Garg P, et al. Concomitant infection of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in an outbreak of cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139 in Ahmedabad, India. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(9):3241-3246.

Crossref - Begum YA, Talukder KA, Azmi IJ, et al. Resistance Pattern and Molecular Characterization of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) Strains Isolated in Bangladesh. PLOS ONE. 2016 11(7):e0157415.

Crossref - Kumar HS, Otta SK, Karunasagar I, Karunasagar I. Detection of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) in fresh seafood and meat marketed in Mangalore, India by PCR. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2001;33(5):334-38.

Crossref - Kumaran S, Deivasigamani B, Alagappan K, Sakthivel M, Karthikeyan R. Antibiotic resistant Esherichia coli strains from seafood and its susceptibility to seaweed extracts. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2010;3(12):977-981.

Crossref - Singh AS, Lekshmi M, Prakasan S, Nayak BB, Kumar S. Multiple antibiotic-resistant, extended spectrum-b-lactamase (ESBL)-producing enterobacteria in fresh seafood. Microorganisms. 2017;5(3):53.

Crossref - Koo HJ, Woo GJ. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli recovered from foods of animal and fish origin in Korea. J Food Prot. 2012;75(5):966-972.

Crossref - Ryu SH, Lee JH, Park SH, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles among Escherichia coli strains isolated from commercial and cooked foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;159(3):263-266.

Crossref - Miranda CD, Zemelman R. Antibiotic resistant bacteria in fish from the Concepcion Bay, Chile. Mar Pollut Bull. 2001;42(11):1096-1102.

Crossref - Van TTH, Moutafis G, Tran LT, Coloe PJ. Antibiotic resistance in food-borne bacterial contaminants in Vietnam. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007; 73(24):7906-7911.

Crossref - Changkaew K, Utrarachkij F, Siripanichgon K, Nakajima C, Suthienkul O, Suzuki Y. Characterization of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from shrimps and their environment. J Food Prot. 2014;77(8):1394-1401.

Crossref - Rees EE, Davidson J, Fairbrother JM, St. Hilaire S, Saab M, McClure JT. Occurrence and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli in oysters and mussels from Atlantic Canada. FPD. 2015;12(2):164-169.

Crossref - Nadimpalli M, Vuthy Y, de Lauzanne A, et al. Meat and fish as sources of extended-spectrum b-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli, Cambodia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(1):126.

Crossref - Mandal A, Sengupta A, Kumar A, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Extended-Spectrum b-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Pathotypes in Diarrheal Children from Low Socioeconomic Status Communities in Bihar, India: Emergence of the CTX-M Type. Infect Dis Res Treat. 2017;10:1178633617739018.

Crossref - Ghosh D, Chowdhury G, Samanta P, et al. Characterization of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli with special reference to antimicrobial resistance isolated from hospitalized diarrhoeal patients in Kolkata, India. J Appl Microbiol. 2022;132(6):4544-4554.

Crossref - Van Minh H, Nguyen-Viet H. Economic Aspects of Sanitation in Developing Countries. Environ Health Insights. 2011;5:EHI-S8199.

Crossref - Eliakim-Raz N, Lador A, Leibovici-Weissman Y, Elbaz M, Paul M, Leibovici L. Efficacy and safety of chloramphenicol: joining the revival of old antibiotics? Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAC. 2015;70(4):979-996.

Crossref - Grossman TH. Tetracycline Antibiotics and Resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6(4):a025387.

Crossref - Pouwels KB, Batra R, Patel A, Edgeworth JD, Robotham JV, Smieszek T. Will co-trimoxazole resistance rates ever go down? Resistance rates remain high despite decades of reduced co-trimoxazole consumption. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;11:71-74.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.