ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common clinical diseases worldwide, affecting around 150 million people annually. Despite extensive efforts, the prevalence of UTIs remains high. This study aimed to investigate antibiotic resistance and virulence genes in pathogenic Escherichia coli (E. coli) isolated from UTI patients at Al-Hussein Hospital, Nasiriyah City, Iraq. A total of 250 urine samples were collected, with 77% of patients being female and 23% male. Age distribution included 13% under 20 years, 33% aged 20-40, 35% aged 40-60, and 19% aged 60 years or older. The most common UTI types included 20% complicated UTIs, 25% uncomplicated UTIs, 30% community-acquired UTIs, and 25% healthcare-associated UTIs. Among the E. coli isolates, antibiotic resistance was observed, with ceftizoxime (CZX 30 mcg) showing the lowest resistance at 21.6%, followed by ceftriaxone (CTR 30 mcg) at 26%, cefpirome (CFP 30 mcg) at 22.8%, and cefepime (CPM 30 mcg) at 12.4%. The highest resistance was found with cefadroxil (CFR 30 mcg) at 30.8%. Additionally, the study detected several virulence and resistance genes, including papAH (8%), saf (10.8%), kps (8%), yfcV (12%), ST131 (20.4%), VAT (11.6%), OqxA (6%), and blaCTX-M (7.2%). These findings emphasize the need for better understanding the genetic makeup of E. coli in UTIs, aiding in the development of diagnostic and treatment strategies.

Urinary Tract Infections, Escherichia coli, Antibiotic Resistance, Virulence Genes, Genetic Characteristics

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) represent a significant global health issue, affecting individuals across both community and hospital settings. These infections often lead to a substantial decline in the quality of life for patients. The role of antibiotic-resistance genes in Escherichia coli (E. coli) strains responsible for UTIs is profound, influencing clinical management and posing challenges to public health. The following are key implications of antibiotic resistance in the context of UTIs.

Antibiotic resistance genes in E. coli strains complicate the selection of effective antimicrobial therapies for UTIs, often resulting in treatment failures and prolonged illness. As resistance increases, treatment options become more limited, leading to the need for broader-spectrum or more potent antibiotics. However, such antibiotics are typically reserved for severe cases due to their potential side effects, further complicating management.1,2

In addition, UTIs caused by antibiotic-resistant E. coli strains are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. These infections are often more severe or recurrent, making them challenging to treat and increasing the risk of adverse outcomes for patients.3,4

The presence of antibiotic resistance genes in E. coli also contributes to higher healthcare costs. The need for alternative, often more expensive, antibiotic regimens and prolonged hospitalizations places a financial burden on healthcare systems and patients alike.5,6 Furthermore, resistant E. coli strains act as reservoirs for antibiotic resistance genes, which can spread within healthcare settings and the broader community. This dissemination of resistance has the potential to affect the treatment of various infections, not only UTIs, and undermines the effectiveness of available antibiotics.7,8

The public health implications of antibiotic resistance in E. coli UTIs are considerable, requiring coordinated efforts to monitor, control, and prevent the spread of resistant strains. Such efforts are crucial to safeguarding patient outcomes and preserving the efficacy of current antibiotics. Additionally, the importance of ongoing surveillance and antimicrobial stewardship programs cannot be overstated, as they promote the judicious use of antibiotics to mitigate resistance and ensure continued treatment options.9-11

Moreover, the study of antibiotic resistance genes in E. coli UTI strains is driving research into novel antimicrobial agents, alternative treatment strategies, and methods to combat resistance. This highlights the urgent need for the development of new antibiotics and non-antibiotic interventions to address the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance.12,13

Understanding the role of antibiotic-resistance genes in E. coli UTIs is essential for informing clinical decision-making, shaping public health policies, and guiding research efforts aimed at combating the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance in UTIs and related infections.

P fimbriae-encoding genes, like papAH, play a key role in how E. coli causes UTIs. These genes help the bacteria attach to uroepithelial cells, which is the first step in establishing an infection. By sticking to specific receptors on host cells, papAH is essential for both starting and maintaining a UTI.14,15 Similarly, saf encodes S fimbriae, which are critical for E. coli to latch onto and invade the cells in the urinary tract. This ability to stick and invade is crucial because it helps the bacteria dodge the body’s defenses and persist in the urinary system. Beyond adhesion, kps is another gene that plays a big part in E. coli’s virulence. It’s responsible for making the bacterial capsule, which acts as a protective shield. This capsule not only helps E. coli hide from the immune system but also makes it more resistant to antibiotics, allowing the bacteria to stick around longer in the urinary tract. This protective barrier makes the pathogen much harder to eliminate, whether through the immune system or treatment.16,17 Along with this, yfcV helps E. coli scavenge iron from the host. Iron is a vital nutrient for bacteria, and by grabbing it from the body, yfcV supports bacterial growth and survival, which in turn strengthens the infection.

In addition, ST131, a gene involved in quorum sensing, helps E. coli communicate and coordinate its attack. Through quorum sensing, the bacteria can synchronize the production of virulence factors and biofilm formation, which are crucial for adapting and surviving in the urinary tract. These mechanisms allow E. coli to better thrive in tough conditions and make it more resilient within the host.18,19 Meanwhile, the VAT gene encodes a variety of factors, such as adhesins and toxins, which further empower E. coli to invade tissues and maintain an ongoing infection.

A major challenge in treating UTIs caused by E. coli is the development of antibiotic resistance, much of which is driven by genes like OqxA. This gene encodes an efflux pump, which acts like a bacterial “bouncer” that pushes antibiotics out of the bacterial cell, allowing E. coli to survive even in the presence of drugs. Another gene, CTX-M, encodes extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), which make E. coli resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics like cephalosporins. This resistance makes it especially tough to treat UTIs caused by E. coli, especially when these ESBL-producing strains are present.20,21

Recent research shows that antimicrobial resistance in E. coli strains causing UTIs is on the rise, which is becoming a major concern.22,23 This growing resistance underscores the urgent need to better understand the genetic mechanisms behind it, along with the microbiological profile of UTIs, to develop more effective treatments. As resistance continues to spread, it’s crucial to recognize the severity of antibiotic-resistant E. coli strains and fully understand how they work, so that targeted treatments can be developed to tackle them more effectively.24,25

Recent studies have provided deeper insights into the global dissemination of Escherichia coli ST131 and its genetic diversity. Ruzickova et al.26 analyzed 898 ST131 isolates from human, animal, and environmental sources in the Czech Republic and identified clades C1 and C2 as the most dominant. These clades carried high rates of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) genes, particularly blaCTX-M-15 in clade C2 and blaCTX-M-27 in clade C1. Their findings support the notion that ST131 plays a central role in the spread of antibiotic resistance, including resistance to fluoroquinolones and multiple other antibiotic classes.

The dissemination of multidrug-resistant E. coli ST131 in urinary tract infections has also been documented in outpatient settings. A recent study from Croatia by Anusic et al.27 confirmed that around 30% of fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli strains isolated from community-acquired UTIs belonged to the ST131 clone, with over 60% of those producing ESBL enzymes. This aligns with the global trend of ST131 being associated with both fluoroquinolone resistance and ESBL production, posing a serious therapeutic challenge in outpatient care.

A recent study by Balbuena-Alonso et al.28 characterized a highly virulent and multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli strain belonging to an emerging sublineage of ST131, isolated from a patient with a urinary tract infection. The isolate harbored 14 antimicrobial resistance genes and 19 virulence genes, including multiple fimbrial operons (such as fim, pap, yfc, and foc), the high-pathogenicity island encoding yersiniabactin, and the salmochelin operon iro. Additionally, the strain contained genes encoding for serum resistance, toxins, and immune evasion, and showed resistance to third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides. This combination of extensive virulence and resistance highlights the potential of certain ST131 sublineages to cause severe extraintestinal infections such as UTIs, and underlines the need for close molecular surveillance of evolving clonal lineages.

In a recent study from Iran, Memar et al.29 investigated 100 uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) isolates obtained from nosocomial urinary tract infections. The isolates demonstrated a high prevalence of multidrug resistance (MDR), with 87% classified as MDR and 62% producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs). High resistance rates were recorded for piperacillin (82%), aztreonam (81%), and ciprofloxacin (81%), while meropenem showed the lowest resistance (9%). Virulence gene screening revealed a high frequency of fimA (74%), hlyF (68%), and papA (44%), with many isolates also capable of forming strong or moderate biofilms. These findings underscore the complex interplay between resistance and pathogenicity in UPEC strains isolated from hospitalized patients.

A recent longitudinal study by Feng et al.30 investigated 137 Escherichia coli isolates collected over a 12-year period in a Chinese hospital, offering deep insight into the genetic evolution of resistance and virulence. ST131 was the most dominant sequence type, accounting for 18.9% of isolates, and was strongly associated with multidrug-resistance (MDR). Notably, their genomic analysis revealed a rising prevalence of key resistance genes such as blaCTX-M, blaOXA, fos, and sul, particularly in ST131 strains, as well as the presence of co-located virulence and resistance determinants. The study also documented extensive clonal diversity and intra-ST heterogeneity, highlighting the dynamic nature of E. coli evolution under clinical antibiotic pressure.

Biggel et al. conducted a large-scale genomic analysis of 1,638 Escherichia coli ST131 isolates and revealed a significant convergence between virulence and antimicrobial resistance (AMR).31 Their study showed that sublineages harboring the papGII gene-particularly within clade C2-carried significantly more resistance genes than papGII-negative isolates. These strains exhibited resistance to fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and often possessed chromosomally integrated blaCTX-M-15. Notably, papGII+ sublineages became increasingly prevalent after 2005 and now account for nearly half of ST131 bloodstream isolates. The work highlights how the co-selection and genetic convergence of AMR and virulence in ST131 sublineages present a growing threat in urinary tract and bloodstream infections.

The study was conducted at Al-Hussein Hospital in Nasiriyah City, Iraq, where 250 urine samples were collected from patients diagnosed with UTIs between December 1, 2022, and December 1, 2023. The primary aim was to examine the demographic characteristics of the patients, antibiotic resistance among E. coli isolates, and the prevalence of specific resistance genes. The patient sample ranged in age from 20 to 60 years, with data collected on their sex and reported UTI symptoms.

The study also assessed the antibiotic resistance patterns of the isolated E. coli strains, testing their resistance against several antibiotics, including Ceftizoxime (CZX 30 mcg), Ceftriaxone (CTR 30 mcg), Cefpirome (CFP 30 mcg), Cefepime (CPM 30 mcg), Ceftazidime (CAZ 30 mcg), Cefadroxil (CFR 30 mcg), and Cefuroxime (CXM 30 mcg). In addition, the prevalence of various antibiotic-resistance genes was analyzed, focusing on genes such as papAH, saf, kps, yfcV, ST131, VAT, OqxA, and CTX-M.

The laboratory work was supported by a range of instruments and equipment, including autoclaves, centrifuges, compound light microscopes, and digital cameras, among others. Chemical and biological materials, such as agarose, ethanol, and iodine solution, were also used for processing and analysis. These tools and materials were essential for accurately isolating and identifying the bacteria, as well as testing for antibiotic resistance and the presence of resistance genes.

The culture of E. coli was performed using brain heart infusion broth. Upon receipt in the laboratory, specimens were immediately inoculated. If the material was cultured directly from a swab, the swab was inserted into the broth following the inoculation of plated media. In the case of liquid specimens, a loopful was transferred into the broth medium using a sterile loop, or alternatively, the specimen was aseptically pipetted onto a plated medium before being added to the broth. After inoculation, the tubes were incubated with the caps loosely secured in appropriate atmospheric conditions, maintaining a temperature between 33 °C and 37 °C. The cultures were incubated for up to 72 hours, with checks for growth carried out at intervals between 24 and 72 hours.

For the presumptive identification and confirmation of microorganisms responsible for UTIs, HiCrome™ UTI Agar was used. The preparation of the medium involved suspending 32.45 grams in 1000 ml of purified or distilled water, heating it to boiling to ensure complete dissolution, and sterilizing by autoclaving at 15 lbs of pressure (121 °C) for 15 minutes. After cooling to a temperature between 45 °C and 50 °C, the medium was mixed well and poured into sterile Petri dishes. Similarly, HiCrome™ E. coli Agar was employed for detecting and enumerating E. coli in food samples without further confirmation via membrane filtration or indole reagent. This agar can also be used to isolate and cultivate E. coli from clinical samples. To prepare this medium, 36.57 grams were dissolved in 1000 ml of distilled water, boiled, sterilized, and poured into sterile Petri dishes after cooling to the appropriate temperature.

HiCrome™ ESBL Agar Base was utilized for the detection of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)-producing organisms. The medium was prepared by suspending 40 grams in 1000 ml of distilled water, followed by boiling and autoclaving at 15 lbs of pressure (121 °C) for 15 minutes. After cooling to 45-50 °C, the rehydrated contents of two vials of HiCrome™ ESBL Selective Supplement (FD278) were added, and the mixture was poured into sterile Petri plates.

For antimicrobial susceptibility testing, Mueller-Hinton agar was prepared by dissolving 38 grams of Mueller-Hinton agar powder in 1 liter of distilled water. The solution was heated to boiling with frequent agitation and autoclaved, then cooled to 50 °C before being poured into sterile Petri dishes to solidify at room temperature. The Petri dishes were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours to ensure sterilization before being used in antimicrobial susceptibility tests.

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined using the disc diffusion method, as outlined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). To prepare the bacterial inoculum, overnight bacterial growth was obtained in a shaker incubator at 150 rpm and 37 °C. A sterile loop was used to select 3 to 5 identical colonies, which were then suspended in 3 ml of normal saline. The density of the suspension was checked with a density checker apparatus to ensure it matched the McFarland turbidity standard of 0.5, equivalent to 1.5 x 108 CFU/ml.

To determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), the microdilution method was used. The bacterial strain was cultured overnight in Mueller-Hinton broth containing 1% sucrose to induce biofilm gene expression, then diluted to reach a turbidity equivalent to 0.5 McFarland standard (1.5 × 108 CFU/ml) using the density checker apparatus.

For inoculating the testing plates, sterile cotton swabs were dipped into the bacterial suspension and streaked across the surface of the Mueller-Hinton agar plates. The swab was streaked multiple times, rotating the plate 60° each time to ensure an even distribution of the inoculum. After inoculation, the plates were left to dry at room temperature for 5 minutes before the antibiotic discs were applied. The plates were then incubated for the required period before measuring the zones of inhibition to determine antibiotic susceptibility.

Antibiotics disc plating

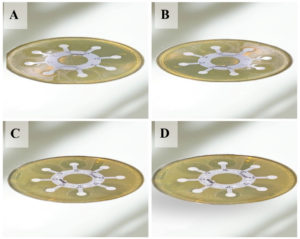

Figure 1 shows the results of the antibiotic susceptibility test performed on Mueller-Hinton agar with E. coli isolates (A, B, C, and D), corresponding to isolates number 9, 18, 27, and 31, respectively. The antimicrobial susceptibility tests were conducted using the Disc Diffusion Method, following the guidelines established by the CLSI. The bacterial inoculum was prepared from overnight cultures of E. coli, ensuring that the bacterial density matched the McFarland turbidity standard of 1.5 × 108 CFU/ml. After inoculating the Mueller-Hinton agar plates with the bacterial suspension, the plates were allowed to dry at room temperature to ensure even distribution of the inoculum. Antibiotic discs, including those for commonly used agents like Ceftizoxime, Ceftriaxone, and Cefepime, were placed on the surface of the inoculated plates. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 18-24 hours to allow bacterial growth and the formation of inhibition zones around the antibiotic discs. After incubation, the diameters of these inhibition zones were measured precisely, and the results were interpreted in accordance with CLSI standards for Enterobacteriaceae susceptibility. Figure 1 visually depicts the inhibition zones formed, providing a clear representation of how the E. coli isolates responded to the various antibiotics. The size and presence of these zones are essential for assessing the resistance profiles of the isolates and guiding the selection of appropriate antimicrobial therapies.

Figure 1. Antibiotic test on Mueller-Hinton agar with some E. coli isolates (A, B, C, and D) referred to E. coli isolates number 9, 18, 27, and 31 respectively

Table 1 provides the primers used in the PCR program for gene detection, detailing the PCR product sizes and the references for each primer. These primers, which are crucial for the amplification process, were selected based on the target genes listed in the table, aiding in the detection of E. coli.

Table (1):

Primers used to detect E. coli

| Primer name | Sequences 5’_’3 | TM (°C) | PCR product (bp) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PapAH | F | ATGGCAGTGGTGTCTTTTGGTG | 61 | 720 | 32 |

| R | CGTCCCACCATACGTGCTCTTC | ||||

| saf | F | CTCCGGAGAACTGGGTGCATCTTAC | 71 | 410 | 33 |

| R | CGGAGGAGTAATTACAAACCTGGCA | ||||

| kps | F | GCGCATTTGCTGATACTGTTG | 57 | 272 | 32 |

| R | CATCCAGACGATAAGCATGAGCA | ||||

| yfcV | F | ACATGGAGACCACGTTCACC | 57 | 292 | 34 |

| R | GRAARCRGGAARGRGGRCAGG | ||||

| ST131 | F | GACTGCATTTCGTCGCCATA | 55 | 310 | 35 |

| R | CCGGCGGCATCATAATGAAA | ||||

| vat | F | TCAGGACACGTTCAGGCATTCAGT | 69 | 1100 | 34 |

| R | GGCCAGAACATTTGCTCCCTTGTT | ||||

| OqxA | F | CTCGGCGCGATGATGCT | 61 | 392 | 36 |

| R | CCACTCTTCACGGGAGACGA | ||||

| blaCTX-M | F | TTTGCGATGTGCAGTACCAGTAA | 57 | 590 | 37 |

PCR program for gene detection

PCR was used to detect specific genes, with a reaction mixture prepared to a final volume of 25 µl. The mixture included 12.5 µl of master mix, containing bacterially derived Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl2, and a reaction buffer at optimized concentrations to ensure efficient amplification of DNA templates. To this, 3 µl of DNA template (12 ng) was added, along with 0.5 µl of each forward and reverse primer (10 pmol). The remaining 8.5 µl of the mixture consisted of nuclease-free water, completing the amplification reaction.

As detailed in Table 2, a total of 250 samples were collected from patients diagnosed with a UTI to analyze the distribution of sex and age among the sample population. Of the study participants, 77% were females (193 individuals), and 23% were males (57 individuals), indicating a higher prevalence of UTIs among females in this particular sample group.

Table (2):

Distribution of Sex and Age among the sample collection

| Items | No | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Females | 193 | 77% |

| Males | 57 | 23% | |

| Age | <20 years | 32 | 13% |

| 20-40 | 83 | 33% | |

| 40-60 | 88 | 35% | |

| >60 | 47 | 19% |

Regarding age distribution, the participants were categorized into four age groups: 13% of the patients were under 20 years of age (32 individuals), 33% were aged between 20 and 40 years (83 individuals), 35% were in the 40-60 year age range (88 individuals), and 19% were over 60 years old (47 individuals). This distribution provides insight into the varying age groups affected by urinary tract infections and highlights the significant portion of patients within the 20-60 year age range, with a notable proportion of those above 60 as well.

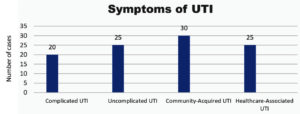

Figure 2 presents the distribution of UTI symptoms among the study sample. The data reveals that 20% of participants reported symptoms associated with complicated UTIs, while 25% reported symptoms of uncomplicated UTIs. Additionally, 30% of the participants experienced community-acquired UTIs, and another 25% reported symptoms of healthcare-associated UTIs. This distribution provides a clear overview of the different types of UTIs and their prevalence within the sample, highlighting the most common symptoms observed in the study population.

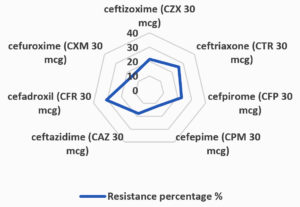

The results presented in Table 3 and Figure 3 highlight the varying degrees of antibiotic resistance observed among E. coli strains isolated from urinary tract infections. The study reveals that CZX 30 mcg exhibited the lowest resistance rate at 21.6%, while CTR 30 mcg had a resistance rate of 26%. CFP 30 mcg demonstrated a resistance percentage of 22.8%. CPM 30 mcg displayed the lowest resistance among the antibiotics tested, at just 12.4%. Ceftazidime (CAZ 30 mcg) showed a resistance rate of 18%, and CFR 30 mcg exhibited the highest resistance at 30.8%. Finally, CXM 30 mcg showed a resistance rate of 15.6%. These findings are critical in understanding the antibiotic resistance patterns of E. coli strains and provide valuable insights for clinicians in selecting the most effective treatment options. The high resistance observed with CFR 30 mcg and ceftriaxone, in particular, underscores the growing concern of antimicrobial resistance and the need for ongoing monitoring to inform therapeutic strategies.

Table (3):

Antibiotic resistance among the isolated E. coli

| No. | Antibiotic Name | Total test | Resistant isolates | Resistance percentage | Non-Resistant Isolates | Resistance percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CZX 30 mcg | 250 | 54 | 21.6% | 196 | 78.4% |

| 2 | CTR 30 mcg | 250 | 65 | 26.0% | 185 | 74.0% |

| 3 | CFP 30 mcg | 250 | 57 | 22.8% | 193 | 77.2% |

| 4 | CPM 30 mcg | 250 | 31 | 12.4% | 219 | 87.6% |

| 5 | CAZ 30 mcg | 250 | 45 | 18.0% | 205 | 82.0% |

| 6 | CFR 30 mcg | 250 | 77 | 30.8% | 173 | 69.2% |

| 7 | CXM 30 mcg | 250 | 39 | 15.6% | 211 | 84.4% |

| Chi-square: 35.642 | Df:6 | P: 0.00000324 | ||||

Table (4):

Prevalence of gene results

| No | Gene name | Total | No. Positive | % | No. Negative | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | papAH | 250 | 20 | 8.0 | 230 | 92.0 |

| 2 | saf | 250 | 27 | 10.8 | 223 | 89.2 |

| 3 | kps | 250 | 20 | 8.0 | 230 | 92.0 |

| 4 | yfcV | 250 | 30 | 12.0 | 220 | 88.0 |

| 5 | ST131 | 250 | 51 | 20.4 | 199 | 79.6 |

| 6 | VAT | 250 | 29 | 11.6 | 221 | 88.4 |

| 7 | OqxA | 250 | 15 | 6.0 | 235 | 94.0 |

| 8 | CTX-M | 250 | 18 | 7.2 | 232 | 90.8 |

| Total | 2000 | 210 | 1790 | |||

| Chi-square: 38.627 | Df: 7 | P: 0.0000023 | ||||

Table 4 presents the prevalence of various genetic markers detected in E. coli isolates using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). The results indicate the following prevalence rates for each gene: The papAH gene was found in 20 samples, accounting for 8% of the total isolates. The saf gene was present in 27 isolates, which represents 10.8% of the sample population. The kps gene was detected in 20 isolates, comprising 8% of the total samples. The yfcV gene was identified in 30 samples, corresponding to 12% of the isolates. The ST131 gene was the most prevalent, found in 51 isolates, making up 20.4% of the population. The VAT gene appeared in 29 isolates, representing 11.6% of the total. The OqxA gene was observed in 15 isolates, constituting 6% of the samples, while the CTX-M gene was present in 18 isolates, or 7.2% of the total population. These findings provide valuable insights into the distribution of genetic markers within the studied isolates, which may have implications for understanding antimicrobial resistance patterns.

The study aimed to investigate the molecular characteristics of E. coli strains isolated from patients with UTIs, focusing on the genetic mechanisms underlying antibiotic resistance in these pathogens. Among the 250 samples collected, 77% were from females and 23% from males, which aligns with findings from Poltorak et al., and Abbo and Hooton,38,39 who reported a similar distribution of 75% females and 25% males in their study on urinary tract infections, their epidemiology, mechanisms of infection, and treatment options. In terms of age distribution, 13% of the study participants were under 20 years of age, 33% were between 20 and 40 years, 35% were in the 40-60 year range, and 19% were over 60 years old. These results were consistent with those found by WHO40 and Wagenlehner et al.,41 who reported in their study on outpatient urinary tract infections that 14% of participants were under 20 years, 31% were aged 20-40, 35% were 40-60, and 20% were over 60 years.

Regarding the most common symptoms of UTIs in the study sample, 20.0% of participants reported suffering from complicated UTIs, while 25.0% experienced uncomplicated UTIs. In addition, 30.0% of the participants complained of community-acquired UTIs, and 25.0% reported symptoms related to healthcare-associated UTIs. These results are in line with the findings of Kass and Durack,42,43 who, in their work “Urinary tract infections: Microbial pathogenesis, host-pathogen interactions, and new treatment strategies”, reported a slightly different distribution. Their study found that 22.0% of patients complained of complicated UTIs, 23.0% suffered from uncomplicated UTIs, 31.0% were diagnosed with community-acquired UTIs, and 24.0% had healthcare-associated UTIs. These similarities indicate that the prevalence of UTI symptoms observed in the present study is consistent with previous research, underscoring the general patterns seen in UTI diagnoses across different patient populations. Furthermore, the study provides valuable insight into the distribution of these symptoms, which could inform clinical practices and help guide effective treatment strategies for patients with UTIs. The high prevalence of community-acquired UTIs and healthcare-associated UTIs emphasizes the importance of both outpatient and hospital-related management strategies in addressing these infections.

The results in Table 2 of the study indicate varying degrees of antibiotic resistance among the isolated E. coli strains. The current study revealed that CZX 30 mcg exhibited the lowest resistance percentage at 21.6%, with 54 out of 250 isolates displaying resistance. CTR 30 mcg showed a slightly higher resistance percentage at 26%, with 65 resistant isolates. CFP 30 mcg demonstrated a resistance percentage of 22.8%, affecting 57 isolates. CPM 30 mcg displayed a lower resistance percentage at 12.4%, with 31 isolates showing resistance. CAZ 30 mcg had an 18% resistance rate, affecting 45 isolates. CFR 30 mcg exhibited the highest resistance percentage at 30.8%, with 77 isolates displaying resistance. Finally, CXM 30 mcg showed a resistance percentage of 15.6%, with 39 resistant isolates. The results disagreed with those of Stamm and Norrby.44 and Smith et al.,45 who stated that CZX 30 mcg exhibited a high resistance percentage of 53.3%, with 160 out of 300 isolates displaying resistance. CTR 30 mcg showed a slightly higher resistance percentage at 56.6%, with 170 resistant isolates. CFP 30 mcg demonstrated a resistance percentage of 46.6%, affecting 140 isolates. CPM 30 mcg displayed a lower resistance percentage of 26.6%, with 80 isolates showing resistance. CAZ 30 mcg had a 36.6% resistance rate, affecting 110 isolates. CFR 30 mcg exhibited the highest resistance percentage at 60.0%, with 180 isolates displaying resistance. Finally, CXM 30 mcg showed a resistance percentage of 53.3%, with 160 resistant isolates.

The results presented in Table 4 of the study indicate that PCR was utilized to identify the presence of specific genes, as detailed in the table. The analysis revealed the following prevalence rates for the respective genetic markers among the isolates: the papAH gene was detected in 20 samples, accounting for 8% of the study’s sample population, the saf gene was present in 27 isolates, constituting 10.8% of the total number of isolates examined, and the kps gene was found in 20 samples, representing 8% of the analyzed specimens. The yfcV gene was observed in 30 isolates, corresponding to 12% of the cohort, while the ST131 gene was identified in 51 samples, amounting to 20.4% of the total isolates. The VAT gene was detected in 29 isolates, making up 11.6% of the study’s isolates, and the OqxA gene was recorded in a subset accounting for 6% of the isolates.

The CTX-M gene was present in 7.2% of the collected samples. These results are consistent with those reported by Foxman et al.,6 who highlighted a lower prevalence of the hlyD, papC, and cnf-1 genes in ciprofloxacin-resistant uropathogenic E. coli compared to their susceptible counterparts isolated from southern India. In that study, which involved 200 patients diagnosed with urinary tract infections, the papAH gene was detected in 70 samples, accounting for 35% of the study’s sample population. The saf gene was present in 45 isolates, constituting 22.5% of the total number of isolates examined, and the kps gene was found in 60 samples, representing 30% of the analyzed specimens. The yfcV gene was observed in 55 isolates, corresponding to 27.5% of the cohort, while the ST131 gene was identified in 51 samples, amounting to 20.4% of the total isolates. The VAT gene was detected in 35 isolates, making up 17.5% of the study’s isolates, and the OqxA gene was recorded in a subset accounting for 8% of the isolates. Finally, the CTX-M gene was present in 10.2% of the collected samples.

The present study found a blaCTX-M prevalence of 7.2%, which, while lower than global reports, is consistent with the presence of resistant ST131 strains. Ruzickova et al.26 reported a much higher ESBL gene prevalence (approximately 76%) among ST131 isolates in the Czech Republic. Notably, their ST131 isolates carried up to 27 resistance genes, showing multidrug resistance patterns across fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, and sulfonamides. This highlights the genetic diversity and adaptability of ST131 strains and supports our conclusion that continuous surveillance of these lineages is essential for UTI management and antibiotic stewardship.

In our study, the detected prevalence of the ST131 lineage and the blaCTX-M gene (7.2%) appears lower than the rates reported in other countries. Anusic et al.27 reported that more than 60% of ST131 isolates in Croatia were ESBL producers, and over 80% were multidrug-resistant, particularly resistant to beta-lactams, cephalosporins, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. However, they also noted low resistance to nitrofurantoin (6.1%) and fosfomycin (5.3%), which could serve as viable treatment options for uncomplicated UTIs. These findings underscore the growing concern about the spread of ST131 and support the need for ongoing molecular surveillance, especially in community settings.

The detection of virulence genes such as papAH, VAT, yfcV, and the resistance gene blaCTX-M in our isolates aligns with the findings of Balbuena-Alonso et al.,28 who described an ST131 strain with a similarly broad arsenal of virulence and resistance traits. Their isolate carried 14 resistance genes and 19 virulence genes, many of which are also observed in our dataset, albeit at lower frequencies. While their study focused on a single isolate, the deep genomic characterization offers a useful point of comparison and supports our conclusion that ST131 strains circulating in our region are part of a broader pattern of genetic convergence between resistance and pathogenicity.

The resistance and virulence profiles observed in our isolates are consistent with the findings of Memar et al.,29 who reported high rates of ESBL production and multidrug resistance in UPEC strains from nosocomial infections in Iran. Similar to our results, their isolates exhibited resistance to key antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin and cephalosporins, while maintaining susceptibility to meropenem. Additionally, both studies detected fimA and papA among the most frequent virulence genes, and confirmed the presence of biofilm-forming ability in a large proportion of isolates. These parallels emphasize the ongoing global threat of hospital-acquired UTIs caused by highly resistant and virulent E. coli strains, reinforcing the necessity of local antimicrobial surveillance and targeted therapy.

Our findings align with those of Feng et al.,30 who demonstrated a strong association between ST131 and both multidrug resistance and virulence factor enrichment. Their longitudinal genomic surveillance revealed that ST131 strains not only dominated over a 12-year span but also showed increasing trends in harboring plasmid-mediated resistance genes and virulence islands. This mirrors our detection of virulence genes like ST131-associated papAH and resistance determinants such as blaCTX-M in our isolates. Moreover, their identification of intra-ST clonal variation and convergence of resistance and virulence provides genomic-level confirmation of the phenotypic patterns we observed, underscoring the need for continuous genomic monitoring in endemic areas.

The detection of papAH and other virulence genes in our local E. coli isolates echoes findings from Biggel et al.,31 which showed that papGII + ST131 strains were significantly more resistant and virulent than papGII-negative ones. Their global dataset revealed that over 80% of papGII + ST131 isolates belonged to clade C2 and carried blaCTX-M-15, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and other resistance genes. Our lower prevalence of blaCTX-M (7.2%) and ST131 (20.4%) may reflect regional differences in clonal expansion, but the genetic convergence observed in both studies underscores the global nature of the threat posed by emerging ST131 variants.

The study result indicated that CZX 30 mcg exhibited the lowest resistance percentage at 21.6%. CTR 30 mcg showed a resistance percentage of 26%. CFP 30 mcg demonstrated a resistance percentage of 22.8%. CPM 30 mcg displayed a lower resistance percentage at 12.4%, CAZ 30 mcg had an 18% resistance rate, CFR 30 mcg exhibited the highest resistance percentage at 30.8%. Finally, CXM 30 mcg showed a resistance percentage of 15.6%. Regarding to detect specific genes and resistance genes. The findings revealed that papAH (8%), saf (10.8%), kps (8%), yfcV

(12%), ST131 (20.4%), VAT (11.6%), OqxA (6%), and blaCTX-M (7.2%) genes. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the genetic and molecular characteristics of E. coli in UTIs, shedding light on virulence factors and antibiotic resistance mechanisms. Such insights are crucial for the development of effective diagnostic tools, treatment strategies, and preventive measures for UTIs caused by E. coli strains. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the genetic and molecular characteristics of E. coli in UTIs, shedding light on virulence factors and antibiotic resistance mechanisms. Such insights are crucial for the development of effective diagnostic tools, treatment strategies, and preventive measures for UTIs caused by E. coli strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Medical Research at Thi-Qar Health Directorate, Thi-Qar City, Iraq, vide reference number MOH/THQ/ETH/025-2025.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- Schreiber HL IV, Spaulding CN, Dodson KW, Livny J, Hultgren SJ. One size doesn’t fit all: unraveling the diversity of factors and interactions that drive E. coli urovirulence. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(2):28.

Crossref - Neugent ML, Hulyalkar NV, Nguyen VH, Zimmern PE, De Nisco NJ. Advances in Understanding the Human Urinary Microbiome and Its Potential Role in Urinary Tract Infection. mBio. 2020;11(2):e00218-20.

Crossref - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Device-associated Module UTI. Urinary Tract Infection (Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection [CAUTI] and Non-Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection [UTI]). 2025, Accessed on February 13, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/7psccauticurrent.pdf

- Tamadonfar KO, Omattage NS, Spaulding CN, Hultgren SJ. Reaching the End of the Line: Urinary Tract Infections. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7(3):10.1128/microbiolspec.bai-0014-2019.

Crossref - Murray BO, Flores C, Williams C, et al. Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection: A Mystery in Search of Better Model Systems. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:691210.

Crossref - Foxman B. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7(12):653-660.

Crossref - Lipsky BA, Byren I, Hoey CT. Treatment of bacterial prostatitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(12):1641-1652.

Crossref - Terlizzi ME, Gribaudo G, Maffei ME. UroPathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) Infections: Virulence Factors, Bladder Responses, Antibiotic, and Non-antibiotic Antimicrobial Strategies. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1566.

Crossref - Marrs CF, Zhang L, Foxman B. Escherichia coli mediated urinary tract infections: are there distinct uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) pathotypes? FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;252(2):183-190.

Crossref - Mulvey MA, Schilling JD, Martinez JJ, Hultgren SJ. Bad bugs and beleaguered bladders: interplay between uropathogenic Escherichia coli and innate host defenses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(16):8829-8835.

Crossref - Schwab S, Jobin K, Kurts C. Urinary tract infection: recent insight into the evolutionary arms race between uropathogenic Escherichia coli and our immune system. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(12):1977-1983.

Crossref - Spaulding CN, Hultgren SJ. Adhesive Pili in UTI Pathogenesis and Drug Development. Pathogens. 2016;5(1):30.

Crossref - Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(5):269-284.

Crossref - Bruxvoort KJ, Bider-Canfield Z, Casey JA, et al. Outpatient Urinary Tract Infections in an Era of Virtual Healthcare: Trends From 2008 to 2017. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(1):100-108.

Crossref - Klein RD, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: microbial pathogenesis, host-pathogen interactions and new treatment strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18(4):211-226.

Crossref - Asadi Karam MR, Habibi M, Bouzari S. Urinary tract infection: Pathogenicity, antibiotic resistance and development of effective vaccines against Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Immunol. 2019;108:56-67.

Crossref - Harwalkar A, Gupta S, Rao A, Srinivasa H. Lower prevalence of hlyD, papC and cnf-1 genes in ciprofloxacin-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli than their susceptible counterparts isolated from southern India. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7(5):413-419.

Crossref - Svanborg C, Bergsten G, Fischer H, et al. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli as a model of host-parasite interaction. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9(1):33-39.

Crossref - Rittirsch D, Flierl MA, Ward PA. Harmful molecular mechanisms in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(10):776-787.

Crossref - Beutler B. Innate immunity: an overview. Mol Immunol. 2004;40(12):845-859.

Crossref - Ferrandon D, Imler JL, Hetru C, Hoffmann JA. The Drosophila systemic immune response: sensing and signalling during bacterial and fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(11):862-874.

Crossref - Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by the innate immune system. Int Rev Immunol. 2011;30(1):16-34.

Crossref - Casanova JL. Severe infectious diseases of childhood as monogenic inborn errors of immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(51):E7128-E7137.

Crossref - Telenti A, di Iulio J. Regulatory genome variants in human susceptibility to infection. Hum Genet. 2020;139(6-7):759-768.

Crossref - Hagberg L, Hull R, Hull S, McGhee JR, Michalek SM, Svanborg Eden C. Difference in susceptibility to gram-negative urinary tract infection between C3H/HeJ and C3H/HeN mice. Infect Immun. 1984;46(3):839-844.

Crossref - Ruzickova M, Karola I, Nohejl T, et al. Comparative genomics of multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli ST131 from human, animal, and environmental sources in the Czech Republic. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2025;299:118320.

Crossref - Anusic M, Marijan T, Dzepina AM, Ticic V, Grskovic L, Vranes J. A First Report on Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli O25 ST131 Dissemination in an Outpatient Population in Zagreb, Croatia. Antibiotics. 2025;14(2):109.

Crossref - Balbuena-Alonso MG, Camps M, Cortés-Cortés G, Carreón-León EA, Lozano-Zarain P, Del Carmen Rocha-Gracia R. Strain belonging to an emerging, virulent sublineage of ST131 Escherichia coli isolated in fresh spinach, suggesting that ST131 may be transmissible through agricultural products. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13.

Crossref - Memar MY, Vosughi M, Saadat YR, et al. Virulence genes and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Escherichia coli isolated from nosocomial urinary tract infections in the northwest of Iran during 2022-2023: a cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2024;7(11):e70149.

Crossref - Feng C, Jia H, Yang Q, Zou Q. Genetic Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Genes in Escherichia coli Isolates from a Chinese Hospital over a 12-Year Period. Microorganisms. 2025;13(4):954.

Crossref - Biggel M, Moons P, Nguyen MN, Goossens H, Puyvelde SV. Convergence of virulence and antimicrobial resistance in increasingly prevalent Escherichia coli ST131 papGII+ sublineages. Commun Biol. 2022;5(1):752.

Crossref - Johnson JR, Stell AL. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J Infect Dis. 2000 Jan;181(1):261-72. doi: 10.1086/315217. Erratum in: J Infect Dis. 2000;181(6):2122.

- Bouguénec CL, Archambaud M, Labigne A. Rapid and specific detection of the pap, afa, and sfa adhesin-encoding operons in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992. 30:1189-93.

Crossref - Spurbeck RR, Dinh PC Jr, Walk ST, et al. Escherichia coli isolates that carry vat, fyuA, chuA, and yfcV efficiently colonize the urinary tract. Infect Immun. 2012;80(12):4115-22.

Crossref - Doumith M, Day M, Ciesielczuk H, Hope R, Underwood A, Reynolds R, Wain J, Livermore DM, Woodford N. Rapid identification of major Escherichia coli sequence types causing urinary tract and bloodstream infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(1):160-6.

Crossref - Wong MH, Chan EW, Chen S. Evolution and dissemination of OqxAB-like efflux pumps, an emerging quinolone resistance determinant among members of Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(6):3290-7.

Crossref - Zheng H, Zeng Z, Chen S, et al. Prevalence and characterisation of CTX-M β-lactamases amongst Escherichia coli isolates from healthy food animals in China. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39(4):305-10.

Crossref - Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282(5396):2085- 2088.

Crossref - Abbo LM, Hooton TM. Antimicrobial Stewardship and Urinary Tract Infections. Antibiotics (Basel). 2014;3(2):174-192.

Crossref - World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance: Fact Sheet. 2023. Accessed on August 13, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ antimicrobial-resistance.

- Wagenlehner FME, Bjerklund Johansen TE, Cai T, et al. Epidemiology, definition and treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Nat Rev Urol. 2020;17(10):586- 600.

Crossref - KASS EH. Asymptomatic infections of the urinary tract. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1956;69:56-64.

- Durack DT. Detection, Prevention and Management of Urinary Tract Infections. Ann Surg. 1980;192(2):258.

Crossref - Stamm WE, Norrby SR. Urinary tract infections: disease panorama and challenges. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(Suppl 1):S1-S4.

Crossref - Smith AL, Brown J, Wyman JF, Berry A, Newman DK, Stapleton AE. Treatment and Prevention of Recurrent Lower Urinary Tract Infections in Women: A Rapid Review with Practice Recommendations. J Urol. 2018;200(6):1174-1191.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.