ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

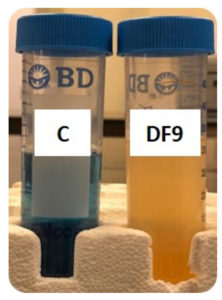

In nature, dibenzofurans are usually found in chlorinated form, which poses a risk to human health and endangers flora and fauna. Bioremediation is recognized as an effective method for addressing contamination in polluted soils. This study aims to identify native bacterial species that degrade dibenzofuran in soils of the Makkah region. Samples were collected from different areas in the region to isolate bacteria that degrade hazardous polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Based on the spectrophotometer and DCPIP assay, thirteen strains were selected. The degradation efficiency of DF9 is the most efficient among them. It was determined that DF9 was Brevibacillus parabrevis. The strain showed the highest absorbance in optical density at 600 nm when measured with a UV spectrophotometer. The selected strain exhibited a notable colorimetric change from blue to white when exposed to 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol dye. Furthermore, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography analysis of strain DF9 substantiated its capacity for degradation, effectively breaking down almost 60% of dibenzofuran. Based on our studies, it can be concluded that Brevibacillus parabrevis YA is an effective strain to clean the environment of hazardous chemicals.

Pollutant, Dibenzofuran, Brevibacillus, Bioremediation

Several methods have been developed to break down crude oil, such as photooxidation, adsorption, volatilization, chemical oxidation, and bioremediation. Dibenzofuran has been reported as a major polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) found in crude oil.1-3 These strategies are typically used to clean up contaminated sites and have received significant attention. In comparison with other techniques, bioremediation is more affordable and sustainable. It was reported that potent bacteria can degrade crude oil and its components.1-3 However, some concerns remain about the byproduct of microorganisms being used to remediate hazardous compounds.4

A variety of biological processes are being affected by a group of toxic chemicals (dioxins), including reproduction, developmental processes, immunity, hormonal imbalance, and carcinogenesis. Therefore, it is an utmost demand to detoxify such omnipresent dioxins from the environment. Moreover, proper guidelines are expected to reduce toxic chemical exposure to humans and monitor industrial processes and strategies to reduce dioxin formation.5

Byproducts of coal tar-related industrial activity include dibenzofuran (DBF) and dibenzo-p-dioxin (DBD). These byproducts result from the bleaching and combustion operations linked to the manufacture of paper pulp. The environment and food contain tiny amounts of these chemicals. They are mostly recognized by chlorine substitutions.6,7 Recent studies have revealed the negative consequences they cause for health and safety.8,9

The degradation of natural environments and the mineralization of xenobiotics and aromatic chemicals are dependent on microorganisms. Rieske non-heme iron-dependent oxygenases primarily encourage the degradation process in oxygen-rich environments. They consist of a Rieske iron-sulfur protein, a reductase, a terminal oxygenase, and associated electron transport proteins. Gibson and Parales stated that these enzymes add dioxygen to facilitate the rapid conversion of aromatic rings into arene cis diols.10 Butler and Mason found that iron-sulfur proteins exhibit catalytic abilities when combined with α-subunits, including Rieske [2Fe-2S] clusters, mononuclear iron sites, and substrate-binding sites, crucial for substrate specificity.10,11 Determining a significant number of evolutionarily related proteins based on amino acid sequences helped us to understand the purpose and evolutionary changes of α-subunit proteins. More study would help to define the biological functions of these proteins. The work of Gibson and Parales demonstrated that groups in the toluene/biphenyl, benzoate, naphthalene, and phthalate subfamilies had strong connections with their natural substrates. Research on microbial biodegradation has turned up a considerable number of bacterial strains capable of breaking down biaryl ethers.10 Many studies have focused on the main bacteria that belong to the phyla Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Janibacter.12-14 In detail, the deoxygenation reaction catalyzed by DBF dioxygenase speeds the breakdown process. The DbfA1 part of this dioxygenase is still unknown, but strains, like DBF63, have enzymes with catalytic properties. Our research reveals that the dioxin dioxygenase from S. wittichii RW1 is quite similar to those enzymes found in strains from the genera Paenibacillus and Terrabacter. Additional branches of the phylogenetic tree of α-subunits have helped us better grasp the mechanisms of microbial degradation. Recent research has reported that several bacterial strains have dioxin-degrading ability. The results endorse the potential applications of these microbes in environmental restoration activities.15,16 The purpose of this study is to identify Makkah microorganisms capable of breaking down dibenzofuran under different environments. We effectively selected strains with great degradation capacity using a spectrophotometer and the DCPIP assay in conjunction with the genetic identification of native strains.

Sampling

Soil sampling

We collected soil samples from thirteen different sites in the Makkah region for this study. The list of the samples with their collection locations is presented in Table 1. Before sample collection, the pH of the soil was monitored. The samples were immediately placed in the icebox and then preserved in the refrigerator.

Table (1):

List of samples and their location

No. |

Sample ID |

Location |

|---|---|---|

1 |

DF9 |

(21.466917,39.899727) Al Muaysim |

2 |

DF22(D) |

(21.379199,39.831417) Makka |

3 |

DF4(b1*) |

(21.467229,39.869858) Makka |

4 |

DF1 |

(21.494944,40.010212) Makka |

5 |

DF2(b) |

(21.516173,40.057827) Makka |

6 |

DF9(b) |

(21.579045,40.123405) Makka |

7 |

DF5(cb1) |

(21.591069,40.122050) Makka |

8 |

DF17(2) |

(21.467928,39.900043) Al Esaela |

9 |

DF7(a2) |

(21.437112,39.264330) Jeddah |

10 |

DF10(a) |

(21.441829,39.265160) Jeddah |

11 |

DFc5(f) |

(21.607658,40.103733) Az Zemah |

12 |

DF28 |

(21.621142,40.101112) Az Zemah |

13 |

DF16(b) |

(21.443396,40.499524) Al Hawiyah |

Bacteria Isolation

One gram of soil from each sample was inserted into 100 mL conical flasks containing Bushnell-Haas broth medium. The flasks were incubated in a shaking incubator for one week at 35 °C. Following incubation, the microbial cultures were spread evenly onto Luria-Bertani agar (LB-agar) and nutrient agar plates. The emerging colonies were meticulously transferred using sterile loops to 5 mL of LB broth and subjected to an overnight incubation under identical conditions of temperature and agitation. Subsequent analysis was conducted on these bacterial isolates to assess their growth capability in environments containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

Characterization

Screening of microorganisms that degrade dibenzofuran

A variety of bacteria were isolated and enriched from soil samples. In the enrichment process, 100 µl of bacterial isolates were inoculated into 200 mL of Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) medium containing 500 mg/L concentrated dibenzofuran and incubated for a week at 35 °C and 180 rpm. After incubation, 1 ml of the culture was serially diluted in distilled water up to a thousand times, then spread on dibenzofuran-containing BHS agar plates, and incubated again at 35 °C for 24 hours. The resulting colonies were purified using LB media under the same conditions and stored in 20% glycerol at -80 °C for future research.

DCPIP (2,6-Dichlorophenolindophenol) Assay

It is a redox-based assay, where DCPIP is oxidised, then turns blue, and when it is reduced, turns colorless. The assay was demonstrated in Bushnell-Hass (BH) medium saturated with 50 mg/L Dibenzofuran (DBF). The isolates were cultured in 5 mL of Luria-Bertani broth, containing 50 mg/L Dibenzofuran, and incubated at 35 °C with 180 rpm for 2 weeks. Later, each of the 1 mL cultured samples was centrifuged at 4000 x g for 5 minutes, and the centrifuged pellet was washed with 0.9% saline water. The suspensions of isolates were adjusted to an optical density of 1.0 at a 660 nm wavelength in a spectrophotometer. Subsequently, 80 µL of each cell suspension was transferred to 850 µL of Bushnell-Hass medium containing 50 µL of ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O) solution (50 mg/L), and 50 µL of a 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol solution (37.5 mg/L) and mixed homogeneously. The assay was incubated at 30 °C with 100 rpm for 48 hours in a dark condition. In this assay, as negative controls, BH-DBF with DCPIP was incubated at the same time. After proper incubation, the assay was evaluated based on the presence or absence of color. The assay retained a colorless appearance, indicating that the respective microorganism could degrade DBF. On the other hand, the assay exhibited a blue coloration, indicating a lack of microbial degradation of DF.

UV-spectrophotometric analysis

To evaluate the degradation of dibenzofuran (DBF), selected bacteria were treated with 500 mg/L of the compound and then incubated under controlled conditions. After a 24-hour incubation period, the absorbance of the samples was measured at 600 nm using a spectrophotometer and compared to a blank. The degradation of dibenzofuran was determined by referencing a linear standard curve and quantified using a formulated mathematical formula. This method allowed for the accurate assessment of the bacteria’s ability to break down dibenzofuran, providing valuable data for further research on bioremediation and environmental cleanup strategies.

D = (C1 – C2) / C x 100%

Where D is the % of degradation. C1 is the initial PAH concentration used, and C2 is the residual concentration used in the experiment.

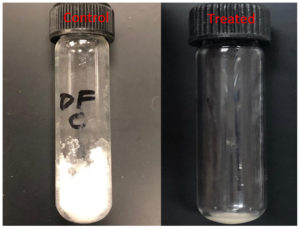

Weight method

Using the weight method, we were able to determine the amount of degradation of dibenzofuran in the presence of bacteria. For this study, the bacteria were grown for two weeks in the presence of dibenzofuran. A two-week culture was then carried out to extract Dibenzofuran using Dichloromethane as a solvent after two weeks of culture.

Calculating dry weight

The procedure was experimented to quantitatively measure the dibenzofuran weight extracted from the culture supernatant. In the first step, the empty tube was weighed, and then the dibenzofuran was transferred to the empty tube and dried then weighed; then the results were compared. For this, the container weight was minus from the Container and sample weight after drying.

Dry sample weight = g (Calculation: B gm – A gm = C gm)

Where A gm is used for container weight, B gm is used for the weight of the sample in the container, and C gm is used for the dry weight of the sample.

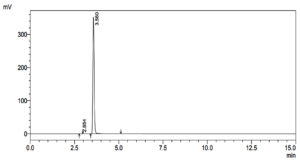

Quantitative analysis using High-performance liquid chromatography

Sample preparation

Dibenzofuran was extracted using a 1:9 dichloromethane (DCM) solution and stored in a 200 microliter amber glass vial at 20 °C before High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis. The extract was collected with a syringe tip and transferred to another vial containing 200 microliters of DCM for HPLC preparation. A control sample was prepared using the same method. A C18 reversed-phase column was used with a stationary phase of octadecylsilane-bonded silica. An acetonitrile-water mixture was used as a mobile phase with a 1 ml/min flow rate. The retention time for dibenzofuran was 6-8 mins under the above conditions.

Molecular identification

Genomic DNA extraction

GeneJET Genomic DNA Extraction Kit was used for DNA extraction from the selected bacterial samples. The first step involved enzymatically releasing DNA from cells, followed by the preparation of columns and washing of the DNA through centrifugation. The DNA was eluted with a buffer, centrifuged further, and collected in a specific tube.

16S rRNA gene amplification

After genomic DNA extraction from the sample was performed using the GeneJET Genomic DNA Extraction Kit, the 16S rDNA was then amplified with specific primers (Forward: 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ and Reverse: 5′-GGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) via PCR thermocycler. The PCR protocol included an initial 8 minute incubation at 94 °C, followed by 25 cycles of 20 second denaturation at 94 °C, 20 second annealing at 54 °C, and 1 minute extension at 72 °C, ending with a final 5 minute extension at 72 °C. The amplified DNA underwent electrophoresis, extraction, purification, sequencing (Macrogen Korea), and analysis with MEGA X software for phylogenetic tree construction.17 The received sequence was submitted to the NCBI data bank to get the accession number for the potent isolates.

Growing in the presence of 0.05% Dibenzofuran, the bacteria native to the Makkah area have shown remarkable endurance; nonetheless, the great molecular size of the molecule usually prevents bacteria from using it. The capacity of these bacteria to not only survive but also flourish in such adverse environments demonstrates their enormous potential for bioremediation and environmental preservation. Through the discovery of new approaches to handling pollutants, greater research on their genes and metabolism might help us raise our capacity in the area of environmental cleaning. We used both quantitative and qualitative methods to find these powerful strains for further investigation. We used DCPIP, a spectrophotometer, and the dry weight technique in qualitative analysis to assess the growth and metabolic activities of the bacteria. Additionally, we used High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for quantitative analysis to measure the quantities of several chemical components. Furthermore, the selected strains are using molecular techniques.

OD (Optical density) using a spectrophotometer

After exposing all bacterial isolates to a 0.05% dibenzofuran environment, only a few bacteria showed survival. Based on its increased optical density readings, Isolate DF9 showed quite significant expansion. Table 2 shows that the positive results have led to the choice of DF9 for more thorough investigation.

Table (2):

Shows the optical density of selected samples based on their growth

No. |

Sample ID |

OD (600 nm) |

|---|---|---|

1 |

DF9 |

1.095 |

2 |

DF22(D) |

0.898 |

3 |

DF4(b1*) |

0.847 |

4 |

DF1 |

0.845 |

5 |

DF2(b) |

0.838 |

6 |

DF9(b) |

0.724 |

7 |

DF5(cb1) |

0.722 |

8 |

DF17(2) |

0.720 |

9 |

DF7(a2) |

0.597 |

10 |

DF10(a) |

0.552 |

11 |

DFc5(f) |

0.415 |

12 |

DF28 |

0.412 |

13 |

DF16(b) |

0.361 |

2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) assay

Using dibenzofuran as the test variable, the strain DF9 was cultivated at 35 °C for two weeks. According to the observations, the control did not change color; but, as Figure 1 shows, the solution, including the bacteria, changed from blue to colorless. This significant color change spurred a deeper study to look at the mechanisms behind the bacterial strain’s response. This finding emphasizes the need to investigate microorganisms’ behavior to improve applications in environmental remediation and biotechnology.

Dry weight

Analytical results indicate a significant reduction in the mass of Dibenzofuran, as shown in Figure 2.

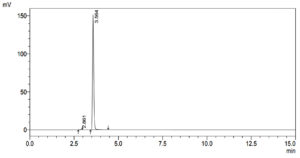

HPLC analysis

To determine if and how much Dibenzofuran was present in the control and treatment samples, qualitative analysis was performed. Figure 3 illustrates the results from the control sample, and Table 3 summarizes them, providing a baseline for comparison. This offers a standard by which to measure. The sample treated, on the other hand, has results shown in Figure 4 and Table 4. These show any changes or effects that the treatment may have had on the levels of Dibenzofuran. This study not only helps with figuring out how well the experimental intervention worked, but it also gives useful information about how the treatment changed the molecule.

Table (3):

HPLC Profile of Untreated Dibenzofuran as a Control

Peak |

Retention Time |

Area |

|---|---|---|

1 |

2.854 |

1419 |

2 |

3.560 |

1852722 |

Total |

1854141 |

Table (4):

HPLC Profile of Dibenzofuran treated with Brevibacillus parabrevis

Peak |

Retention Time |

Area |

|---|---|---|

1 |

2.861 |

1716 |

2 |

3.564 |

750717 |

Total |

752434 |

Molecular analysis

16S rRNA analysis

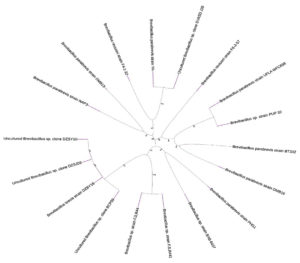

Several Brevibacillus strains from GenBank were closely linked to the 16S rRNA sequence of Brevibacillus parabrevis, which shows that these strains are remarkably like it. The results revealed the conclusions of this investigation.18 Figure 5, illustrating the genetic relationship among the strains, offered a visual depiction of this classification. This finding helps us understand how this group of bacteria evolved, and it also supports the classification of the Brevibacillus parabrevis strain in the Brevibacillus genus.

The presence of microorganisms that are capable of demonstrating remarkable catabolic activities is indisputable. It is unquestionably evident now that microorganisms are capable of occupying polluted sites, and this can expedite the degradation of dibenzofuran in the soil that is polluted by it. In addition to negatively affecting human health, this pollutant has also been shown to have detrimental effects on the environment, marine life, animals, birds, and crops, as well as naturally occurring desert plants and the quality of the overall environment. This study was conducted to identify microorganisms in the soil that could utilize Dibenzofuran as a sole carbon and energy source. Consequently, these microorganisms may serve as effective agents in bioremediation, facilitating the conversion of hydrocarbons into carbon dioxide, water, and humus. Their potential in such environmental applications is noteworthy.19-21

An estimated thirteen different strains of bacteria were isolated from different areas in Makkah for this study. The DF9 strain is one of these strains of bacteria that shows a significant level of degradation activity compared to the rest of the strains. Based on the 16S rRNA primer that was used to identify these bacteria, they were identified as Brevibacillus parabrevis strain YA (MK611770) by molecular methods. Brevibacillus parabrevis strain YA was phylogenetically reconstructed based on other Brevibacillus species that were retrieved from the NCBI website to construct the phylogenetic tree. Similar research was conducted to determine the molecular identities of bacteria involved in the degradation of Dibenzofuran and other polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) under laboratory conditions.22,23

In the process of identifying bacterial isolates that can degrade crude oil, there are three main indicators to look for: a reduction of dibenzofuran (dry weight), as well as an increase in optical density at 600 nm. Using an electron acceptor such as DCPIP, bacteria are able to biodegrade crude oil through incorporating the process with an electron acceptor, such as a metal ion. Since DCPIP is a reagent that changes from blue (oxidized) to colorless (reduced) if it is present in the culture medium, the presence of the reagent indicates a degradation process.24 The bacterial strain Brevibacillus parabrevis YA (DF9) was cultured in a growth medium enriched with dibenzofuran and supplemented with dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP). In one week, the control color turned blue, which appeared to indicate there was no activity going on in the experiment. For the DF9 sample, however, the color changed from blue to colorless, indicating that the sample could degrade Dibenzofuran at a concentration of 500 mg/L that was used in the growth medium. Isolate DF9 has a 1.095 OD at 600 nm wavelength, which is more comparable to the other isolates. Hence, the strain DF9 is considered one of the best Dibenzofuran degraders. Nonetheless, more research needs to be carried out in order to quantify the reliability of this strain in destroying Dibenzofuran in the future. In a similar study, the optical density of bacteria that are growing in the presence of polyaromatic hydrocarbons was also determined.

In the course of qualitative analysis concerning Dibenzofuran (DF), the combined mass of DF along with its test tube was accurately measured. Findings from this study reveal that approximately 100% of dibenzofuran undergoes effective degradation due to the action of Brevibacillus parabrevis strain YA, underscoring the significant degradation potential of this bacterium on dibenzofuran. Supportive research utilizing analogous methodologies has been conducted to determine the optical density of bacteria in environments contaminated with polyaromatic hydrocarbons. Pertinent literature includes investigations by Johnsen et al and Guo et al., which address similar environmental factors.25,26 Additionally, the samples utilized for the dry weight method were subjected to quantitative analysis. During the HPLC analysis, Brevibacillus parabrevis strain YA (DF9) was selected to validate the results previously obtained by UV spectrometry and dry weight assessments alongside those of the HPLC procedure. In the control sample, a retention time of 3.56 was observed, with a peak height of 1852722 and a total area of 1854141. These figures indicate that the control sample comprised approximately 99.92% dibenzofuran with about 0.077% impurities. Upon incubation of Brevibacillus parabrevis strain YA (DF9) with another sample for one week, there were dramatic reductions in both peak area and height by 60%, illustrating significant changes when compared to the control group free from bacterial influence. The peak area was 752434 in the treated sample, while the peak height was 750717. Based on the results of this experiment, it appears that Brevibacillus parabrevis strain YA (DF9) can degrade almost 60% of the dibenzofuran pollutant, which is a toxic waste product. Similar studies have been conducted to quantify polyaromatic hydrocarbons after being treated with different bacteria.26,27

Dibenzofuran, a toxic pollutant from industrial activities and vehicle emissions, builds up in marine life, presenting cancer risks to humans who eat contaminated seafood. This compound harms marine health and disrupts ecosystems. Strengthening emission and waste regulations, reducing product usage, and engaging in beach clean-ups are critical for protecting marine environments and human health. Collective action is vital to minimize pollutants like dibenzofuran and ensure sustainable practices. Thus, based on these points, it is readily apparent that the environment needs to be cleaned through a cost-effective and effective approach to eradicate diseases that originate from contaminants in the environment. In the present work, we examine the ability of the indigenous bacterial isolate from petroleum-contaminated soil to degrade dibenzofuran. In the selected strain, there is almost 100 percent degrading activity for dibenzofurans at an optimal pH value. The isolate was identified as a strain of Brevibacillus parabrevis (MK611771) known as Brevibacillus parabrevis YA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for technical and financial support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

The research was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Lin C, Gan L, Chen ZL. Biodegradation of naphthalene by strain Bacillus fusiformis (BFN). J Hazard Mater. 2010;182(1-3):771-777.

Crossref - Sun R, Jin J, Sun G, Liu Y, Liu Z. Screening and degrading characteristics and community structure of a high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial consortium from contaminated soil. J Environ Sci. 2010;22(10):1576-1585.

Crossref - Anwar Y, El-Hanafy AA, Sabir JSM, et al. Characterization of Mesophilic Bacteria Degrading Crude Oil from Different Sites of Aramco, Saudi Arabia. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds.2017;40(1):135-143.

Crossref - Singh T, Bhatiya AK, Srivastava N, et al. An effective approach for the degradation of phenolic waste. In: Singh P, Kumar A, Borthakur A, eds. Abatement of Environmental Pollutants: Trends and Strategies. Elsevier; 2019:203-243.

Crossref - WHO, work sheet. Dioxins and their effects on human health. 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs225/en/.

- Papke O. PCDD/PCDF: human background data for Germany, a 10-year experience. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(suppl 2):723-731.

- Johansen HR, Alexander J, Rossland OJ, et al. PCDDs, PCDFs, and PCBs in human blood in relation to consumption of crabs from a contaminated Fjord area in Norway. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104(7):756-764.

Crossref - De Angelis M, Schramm KW. Perinatal effects of persistent organic pollutants on thyroid hormone concentration in placenta and breastmilk. Mol Aspects Med. 2021;87:100988.

Crossref - Pajurek M, Mikolajczyk S, Warenik-Bany M. Engine oil from agricultural machinery as a source of PCDD/Fs and PCBs in free-range hens. Environ Sci Poll Res. 2022;30(11):29834-29843.

Crossref - Gibson DT, Parales RE. Aromatic hydrocarbon dioxygenases in environmental biotechnology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2000;11(3):236-243.

Crossref - Butler CS, Mason JR. Structure-function Analysis of the Bacterial Aromatic Ring-hydroxylating Dioxygenases. Adv Microb Physiol. 1996;38:47-84.

Crossref - Iida T, Nakamura K, Izumi A, Mukouzaka Y, Kudo T. Isolation and characterization of a gene cluster for dibenzofuran degradation in a new dibenzofuran-utilizing bacterium, Paenibacillus sp. strain YK5. Arch Microbiol. 2006;184(5):305-315.

Crossref - Lang E, Kroppenstedt RM, Swiderski J, et al. Emended description of Janibacter terrae, including ten dibenzofuran-degrading strains and Janibacter brevis as its later heterotypic synonym. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53(6):1999-2005.

Crossref - Yamazoe A, Yagi O, Oyaizu H. Degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by a newly isolated dibenzofuran-utilizing Janibacter sp. strain YY-1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;65(2):211-218.

Crossref - Thanh LTH, Thi TVN, Shintani M, et al. Isolation and characterization of a moderate thermophilic Paenibacillus naphthalenovorans strain 4B1 capable of degrading dibenzofuran from dioxin-contaminated soil in Vietnam. J Biosci Bioeng. 2019;128(5):571-577.

Crossref - Dinh MTN, Nguyen VT, Nguyen LTH. The potential application of carbazole-degrading bacteria for dioxin bioremediation. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2023;10(1):56.

Crossref - Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) Software Version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1596-1599.

Crossref - Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731-2739.

Crossref - Sei A, Fathepure BZ. Biodegradation of BTEX at high salinity by an enrichment culture from hypersaline sediments of Rozel Point at Great Salt Lake. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107(6):2001-2008.

Crossref - Zhao HP, Wang L, Ren JR, Li Z, Li M, Gao HW. Isolation and characterization of phenanthrene-degrading strains Sphingomonas sp. ZP1 and Tistrella sp. ZP5. J Hazard Mater. 2008;152(3):1293-1300.

Crossref - Li J, Peng W, Yin X, et al. Identification of an efficient phenanthrene-degrading Pseudarthrobacter sp. L1SW and characterization of its metabolites and catabolic pathway. J Hazard Mater. 2024;465:133138.

Crossref - Wong JWC, Lai KM, Wan CK, K K MA, Fang M. Isolation and Optimization of PAH-Degradative Bacteria from Contaminated Soil for PAHs Bioremediation. Water Air Soil Poll. 2002;139(1-4):1-13.

Crossref - Wolter M, Zadrazil F, Martens R, Bahadir M. Degradation of eight highly condensed polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by Pleurotus sp. Florida in solid wheat straw substrate. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48(3):398-404.

Crossref - Hanson KG, Desai JD, Desai AJ. A rapid and simple screening technique for potential crude oil degrading microorganisms. Biotechnology Techniques. 1993;7(10):745-748.

Crossref - Johnsen AR, Wick LY, Harms H. Principles of microbial PAH-degradation in soil. Environ Poll. 2005;133(1):71-84.

Crossref - Guo CL, Zhou HW, Wong YS, Tam NFY. Isolation of PAH-degrading bacteria from mangrove sediments and their biodegradation potential. Mar Poll Bull. 2005;51(8-12):1054-1061.

Crossref - Fulekar MH. Microbial degradation of petrochemical waste-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2017;4(1):28.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.