ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Tick-borne diseases have raised serious health concerns in dogs globally, primarily in hot and humid climate of tropics and subtropics. The molecular detection and characterization of Hepatozoon canis were carried out in extracted DNA from blood samples of dogs (n = 212) by real-time PCR and from vector ticks (n = 41) by conventional PCR targeting the 18S rRNA gene. The present study reported low prevalence of Hepatozoon canis infections in dogs (9%) while high prevalence in Rhipicephalus spp. ticks (33.14%) in dogs in eight coastal districts of Odisha. The PCR positive blood samples (n = 19) were analyzed by multiplex PCR for co-infection, revealing the prevalence of co-infections of H. canis with A. platys (2.5%), with both A. platys and E. canis (0.9%) as well as with A. platys and B. gibsoni (0.9%). Presence of ticks, irregular anti- tick treatment and limited outdoor activity were found to be significantly associated incidence of hepatozoonosis. Hematological values of dogs with hepatozoonosis revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia and neutrophilia, while the group with mixed infection (MI) had significantly lower (P < 0.01) mean Hb, platelets, TEC, PCV, MCV, MCH, MCHC level indicating microcytic hypochromic anemia and potential thrombocytopenia in comparison to single infection (SI). The nucleotide sequence identity study revealed 98%-100% similarity of Odisha isolate with other global isolates of H. canis. The Odisha isolate was closely related to the nucleotide sequences of H. canis, isolated from dogs of West indies, as revealed by the phylogenetic analysis.

Hepatozoon canis, Epidemiology, PCR, Hematology, Transmission

Canine hepatozoonosis is a tick-transmitted infection that occurs in both domestic and wild canids worldwide. It is caused by protozoan parasites of the family Hepatozoidae, under the genus Hepatozoon.1 Two Hepatozoon species have been incriminated in causing canine hapatozoonosis namely: Hepatozoon canis and Hepatozoon americanum. H. canis has a broad geographic range, being reported in Africa, parts of Asia, Europe, and the America, while H. americanum is confined to the United States.2

Unlike most other tick-borne haemoparasites, Hepatozoon canis infects both circulating white blood cells and various tissues, particularly haemolymphatic organs. Transmission occurs through ingestion of an infected Rhipicephalus sanguineus tick instead of bite of tick. It develops asexually by schizogony in a vertebrate intermediate host (dog) and sexual development by sporogony and gametogony in a hematophagous invertebrate definitive host (tick).2

The clinical outcome of H. canis infection ranges from asymptomatic cases to severe disease, with common manifestations including fever, anorexia, loss of condition, anaemia, and hyperglobulinemia, which may progress to pneumonia, glomerulonephritis or hepatitis.3 Coexistence of multiple tick-borne organisms, belonging to genus Babesia, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia frequently occur because they share the same vector, the brown dog tick (R. sanguineus), which is highly prevalent in India.4 These concurrent infections often intensify clinical severity and may reduce the effectiveness of treatment.5

Microscopic examination of peripheral blood smears is the conventional diagnostic approach for H. canis; however, its sensitivity is limited in cases of low or fluctuating parasitemia, particularly in chronically infected or carrier dogs.6 Molecular techniques, especially nucleic acid-based assays, provide superior specificity and sensitivity. Polymerase chain reaction, sequencing as well as phylogenetic analysis are widely used for accurate detection and species identification.7 Real-time PCR (qPCR) not only detects parasite DNA but also quantifies its load, making it valuable for distinguishing between subclinical carriers and clinically diseased animals. It performs amplification of the target gene and analysis of the products, which eliminate the need for gel electrophoresis and staining with carcinogenic dye like ethidium bromide.8 Multiplex PCR assays are also employed globally to detect multiple pathogens and co-infections in a single tube reaction.9 Molecular detection of H. canis infection by targeting highly conserved region of 18S rRNA gene has been proven ideal.10

The hot and humid climatic condition of Indian sub-continent, owing to its subtropical location provides a favorable condition for propagation and sustainment of tick vectors. Molecular detection of H. canis in dogs and ticks has previously been documented in Tamil Nadu, as well as in dogs from a few other states such as Kerala, Mizoram, and Tripura using conventional PCR, and in Punjab using qPCR.11-15 According to the Koppen-Geiger climate classification, Odisha-an eastern coastal state of India-predominantly falls under the Tropical Savanna (Aw) type, which is characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons, high temperatures, and heavy monsoon rainfall.16 Despite being a tick-conducive region, the molecular evidence on prevalence of this pathogen from Odisha was not attempted. Furthermore, information regarding the prevalence of H. canis infection, its epidemiology, risk factors, and molecular characterization in this region is scarce. The current study provides the first molecular detection of H. canis in Odisha and establishes its prevalence in both dogs and vector ticks. The study assessed co-infections, identified potential risk factors, examined hematological changes linked to the infection, and carried out phylogenetic analysis.

Study area

Odisha, lying on coastal region is an eastern state of India, spreading from 17° 49 to 22° 34 N Latitude and 81° 27 to 87° 29 E Longitude with a net geographical area of 1,55,708 km2. For the current study, 8 districts viz. Khordha (20° 11′ N, 85° 40′ E), Cuttack (20° 28′ N, 85° 54′ E), Puri (19° 48′ N, 85° 52′ E), Ganjam (19° 22′ N, 85° 06′ E), Nayagad (20° 08′ N, 85° 08′ E), Bhadrak (21° 06′ N, 86° 50′ E), Jajpur (20° 84′ N, 86° 31′ E) and Jagatsingpur (20° 25′ N, 86° 17′ E) were selected (Figure 1). These districts are located in the coastal belt of the state.

Figure 1. Map of India depicting Odisha and map of Odisha with districts included in the investigation marked by blue triangle52,53

Sampling of animal

The study was carried out from February, 2024 to January, 2025. Dogs presented to Veterinary Clinical Complex (VCC), Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology, Bhubaneswar, Odisha were selected with history/presence of tick infestation, and with or without signs of tick-borne diseases (TBD), such as fever, lymphadenopathy, generalized or limb weakness, respiratory distress, petechiae on skin and visible mucous membrane and bleeding disorder. Total of 212 canine blood samples were aseptically obtained from the cephalic or saphenous vein in EDTA vials. These samples were directly used for preparing thin blood smears and conducting hematological examinations, and subsequently stored at -80 °C for later DNA extraction. The consent for blood collection was obtained from the dog owners for the diagnostic purposes by registered professionals following the guidelines for blood collection stipulated by Committee for the Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CCSEA) and the approval was acquired from Institute of Animal Ethical Committee of the University (833/IAEC, dated- 7-10-2023) for conducting the study. The details on location, sex, age, breed, tick infestation, use of acaricides, and outdoor exposure were documented and evaluated for potential risk factors.

Sampling of ticks

In this study 108 ticks were recovered from 41 infested dogs out of 212 dogs screened. They were identified by their morphology to the genus level17 and were stored at -80 °C for molecular analysis. Ticks collected from a dog were considered as one pooled sample, and DNA was extracted from 41 tick pools.

Microscopy

The blood samples were examined microscopically by preparing thin smears, which were air-dried and fixed with methanol. These smears were stained using 10% Giemsa solution for 40 minutes and observed under an oil immersion objective. The presence of encapsulated, oval-shaped gamonts with a prominent central nucleus of H. canis within neutrophils or monocytes confirmed infection (Supplementary Figure 1).18 Samples were considered negative if no parasites were detected after scanning a minimum of 100 oil immersion fields.19

Haematology

Hematological indicators include total leukocyte count (TLC), differential leukocyte count (DLC), packed cell volume (PCV), platelet count, hemoglobin (Hb), total erythrocyte count (TEC), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean Corpuscular volume (MCV) and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) were measured using an automated Hematology analyzer (Merilyzer Celquant Vet, Meril Life Sciences, India). Ten number of apparently healthy dogs screened negative for the tick-borne infections by multiplex PCR were taken as healthy control.

DNA extraction from ticks and blood

Each pooled tick sample was preserved by freezing and then finely pulverized with liquid nitrogen using a sterilized mortar and pestle for DNA extraction.20 Genomic DNA was isolated from both whole blood samples of dogs and ticks with the DNeasy® Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s guidelines with minor modifications. The step involving PBS addition was omitted, and the DNA was finally eluted in a final volume of 50 µl. The purity and concentration of the extracts were determined using a nano-spectrophotometer, and the samples were stored at -80 °C for future analysis.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays

The primers and cycling conditions used in different types of PCR assays are mentioned in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

Table (1):

The primer sequences used in real-time, singleplex conventional and multiplex PCR assay

| No. | Parasite | Sequence | Size | Target gene | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H. canis | HEP F 5ʹTCA ACT TTA TTAGAA GAG GCG CAT T 3ʹ | 106 bp | 18S ribosomal RNA gene | Thomas et al.15 |

| HEP R 5ʹTTT TCA CTT TGC GAT TTG CTA AGT T 3ʹ | |||||

| 2 | H. canis | HEP F 5ʹCCTGGCTATACATGAGCAAAATCTCAACTT 3ʹ | 737 bp | 18S ribosomal RNA gene | Kledmanee et al.21 |

| HEP R 5ʹCCAACTGTCCCTATCAATCATTAAAGC 3ʹ | |||||

| 3 | B. vogeli | BCV F 5ʹGTGAACCTTATCACTTAAAGG 3ʹ | 602 bp | 18S ribosomal RNA gene | Kaur et al.23 |

| BCV R 5ʹCAACTCCTCCACGCAATCG 3ʹ | |||||

| 4 | B. gibsoni | BAG F 5ʹTGGGGTTTTCCCCTTTTTAC 3ʹ | 489 bp | 18S ribosomal RNA gene | Sathish et al.22 |

| BAG R 5ʹTTC AGC CTT GCG ACC ATA C 3ʹ | |||||

| 5 | A. platys | AP F 5’GCCTTATGGGTCACCAGAGA 3’ | 292 bp | Heat shock protein GroEL gene | Sathish et al.22 |

| AP R 5’TTCAACTTCACGCCTCATTG 3’ | |||||

| 6. | E. canis | EC F 5ʹCAGCCACACTGGAACTGAGA 3ʹ | 817 bp | 16S ribosomal RNA gene | Chen et al.51 |

| EC R 5ʹGAGTGCCCAGCATTACCTGT 3ʹ |

Table (2):

The primer sequences used in real-time, singleplex conventional and multiplex PCR assay

No |

Type of PCR |

Cycling Condition |

|---|---|---|

1 |

Real-time PCR |

95 °C/2 min, 40 cycles of (95 °C/5 s, 60 °C/10 s), 95 °C/30 s, 65 °C/30 s, 95 °C/30 s |

2 |

Singleplex conventional PCR |

95 °C/2 min, 40 cycles of (95 °C/5 s, 60 °C/5 s, 68 °C/10 s), 72 °C/3 min |

3 |

Multiplex conventional PCR |

95 °C/15 min, 35 cycles of (94 °C/30 s, 60 °C/90 s, 72 °C/90 s), 72 °C/10 min |

Quantitative real-time PCR for analysis of blood sample

A real-time singleplex quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was standardized by use of a previously described primer pair targeting the 18S rRNA gene of H. canis that produced an amplicon of 106 bp.14 The reaction volume was set by adding 0.5 µl of each primer (10 µM), 10 µl of Quantinova SYB-green PCR master Mix (2X) (Qiagen, Germany) and a 1 µl eluted DNA. Final 20 µl reaction mixture was made by adding nuclease free water. A two-step quantitative real-time PCR protocol comprising of hot start and amplification followed by melt or dissociation was performed in Real-time PCR system (G8830A, AriaMx system, Agilent, USA).

Singleplex conventional PCR for analysis of tick sample

A conventional singleplex PCR was standardized using a previously described primer pair targeting the 18S RNA gene of H. canis which produced an amplicon of 737 bp.21 A PCR reaction mixture comprising of 20 µl volume was standardized containing 0.5 µl of each primer (10 µM), 10 µl of Fast cycling PCR super Mix (2X) (Qiagen, Germany), 1 µl eluted DNA and 8 µl nuclease free water (NFW).

Multiplex conventional PCR

A multiplex PCR (mPCR) was also performed for detection of co-infections using the eluted DNA from H. canis positive blood samples detected by quantitative real-time PCR with previously used set of oligonucleotide primers specific for H. canis,21 A. platys, B. gibsoni, E. canis22 and B. vogeli23 respectively.

A 50 µl volume of PCR reaction mixture was standardized containing 0.5 µl of each primer (5 pairs each 10 µM), 25 µl of multiplex master Mix (2X) (Qiagen, Germany), 10 µl NFW and a 5 µl template DNA.

The amplifications of conventional PCR were performed using the Thermal Cycler (T100TM Thermal Cycler, Bio-Rad, USA). PCR products were subjected to agarose gel (1.5%) horizontal electrophoresis using ethidium bromide dye (Himedia, India) in Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer at 85V for 60 min along with 100 bp DNA ladder and documented using Ultraviolet gel documentation system (Gel Doc TM EZ Imager, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Sequencing and Phylogenetic analysis

The positive samples of H. canis, which showed a distinct bright band in multiplex PCR, were purified from gels using the QIAquick® Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, GmbH, Germany) as per the manufacturer’s instructions and subsequently sequenced by Eurofins Laboratories, Bangalore. The obtained sequences were aligned using MEGA version 12, and one representative sequence was submitted to the GenBank database under the accession number PV613156. The partial 18S rRNA gene sequence was compared with previously reported sequences available in GenBank. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the MUSCLE algorithm, and similarity with homologous sequences was assessed using nucleotide (nBLAST) Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. Sequence identity analysis was carried out with the Clustal V method, while phylogenetic relationships were inferred from the nucleotide alignments by applying the maximum-likelihood method with 500 bootstrap replications in MEGA 12.24

Statistical analysis

The statistical evaluation was conducted using SPSS version 22 statistical windows software program. The link between multiple risk factors with prevalence of Hepatozoonosis along with other tick-borne haemoparasitic co-infections was determined by the Chi-square test and probability of error was accepted up to 5% (p < 0.05). The Chi-square value (χ2), degrees of freedom and p-values (≤0.05) were evaluated to determine the strength of association between variables. Analyzed risk factors included locality (Khordha, Cuttack, Puri, Ganjam, Nayagad, Bhadrak, Jajpur and Jagatsingpur), sex (male or female), age groups (<1, 1-5, or >5 years), breeds (Non-descriept, Golden Retriever, Labrador, Spitz and others), tick infestation, anti-tick treatments (nil, within 2 months or beyond 2 months) and outdoor activity (nil, limited, feral). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), by Duncan’s multiple comparison tests with post hoc analysis was applied for comparison among groups for hematology.

Among the 212 dogs screened from 8 selected districts, total 04 (1.4%) dogs found to be microscopically positive for H. canis infection, However, 19 (9%) dogs are found to be positive by the SYBR Green based real-time PCR analysis that exposed the Tm values of 74.0 °C and the CT value of 35 was set as the cut-off for positivity (supplementary Figure 2). The significant difference (χ2 = 41.41, df = 1, p = 0) between prevalence of both these method depicts higher sensitivity of the real-time PCR assay. Out of 19 qPCR positive samples, Multiplex PCR assay revealed 16 positive cases (7.5%), among which 11 dogs found to have mixed infection while 05 dogs were infected with single pathogen. H. canis was found to be the most commonly co-infected with A. platys in 06 (2.8%) cases. Co-infection of H. canis, E. canis, A. platys and H. canis, A. platys, B. gibsoni was recorded to be 02 (0.9%) in both cases, whereas co-infection of H. canis, B. gibsoni, B. vogeli and A. platys was 01 (0.5%) leading to an overall 57.89% concurrent infection of H. canis with other tick-borne pathogens (TBPs) (Table 3 and supplementary Figure 3). Though there was no significant risk of hepatozoonosis with respect to location, however Jagatsinghpur district revealed the highest prevalence of infection (17.6%) and zero prevalence was recorded from Jajpur district. Among 08 cases of single infection, only 03 dogs revealed clinical signs of intermittent fever, lethargy and emaciation, whereas among 11 cases of mixed infection, 08 dogs revealed signs such as inappetence, lymphadenopathy, tachypnea, fever, pale mucous membranes, hind limb weakness, rhinitis and bloody diarrhea.

Table (3):

Prevalence of H. canis infection and various co-infections in dogs with respect to locality

| District | Total no. of dogs | No of tick infested dogs | Microscopy | PCR Assay | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | HC+AP | HC+AP+EC | HC+BG+AP | HC+AP+BV+BG | ||||

| Khordha | 65 | 10 (15.4) | 2 (3.1) | 6 (9.2) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (3.1) | 0 |

| Cuttack | 32 | 5 (15.6) | 1 (3.1) | 4 (12.5) | 1 (3.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.1) |

| Puri | 21 | 4 (19) | 0 | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ganjam | 22 | 4 (18.2) | 0 | 2 (9.1) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Nayagad | 21 | 8 (38.1) | 0 | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Bhadrak | 15 | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jajpur | 19 | 2 (10.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jagatsingpur | 17 | 6 (35.3) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (17.6) | 2 (11.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 212 | 41 (19.3) | 4 (1.9) | 19 (9) | 6 (2.8) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) |

| Pearson Chi-Square value | 9.757 (0.203) | 4.113 (0.767) | 4.498 (0.721) | 7.461 (0.382) | 7.941 (0.338) | 4.566 (0.713) | 5.68 (0.581) | |

HC: Hepatozoon canis, HC+AP: Hepatozoon canis with Anaplasma platys; HC+AP+EC: Hepatozoon canis with Anaplasma platys and Ehrlichia canis. HC+BG+AP: Hepatozoon canis with Babesia gibsoni and Anaplasma platys. HC+AP+BV+BG: Hepatozoon canis with Anaplasma platys, Babesia vogeli and Babesia gibsoni. The figures in parenthesis for different districts represented in percent

The analysis risk factors associated with prevalence of hepatozoonosis (Table 4) revealed no significant risk of infection associated with breed predisposition, age and sex of dogs. However, highest incidence of hepatozoonosis was found in summer season (9.7%), spitz breed (14.7%), male dogs (9.2%) and younger dogs of <1 year age group (13.2%).

Table (4):

Risk factor analysis for H. canis infection

| Risk factors | Parameters | No. of Dogs | No. of positives | Incidence | χ2 value | Degree of freedom | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season | Summer | 72 | 7 | 9.7 | 0.108 | 2 | 0.947 |

| Rainy | 90 | 8 | 8.9 | ||||

| Winter | 50 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| Breed | Non-descriept | 88 | 7 | 8 | 2.06 | 4 | 0.725 |

| Golden retriever | 20 | 2 | 10 | ||||

| Labrador | 48 | 4 | 8.3 | ||||

| Spitz | 34 | 5 | 14.7 | ||||

| Other | 22 | 1 | 4.5 | ||||

| Sex | Female | 103 | 9 | 8.7 | 0.012 | 1 | 0.911 |

| Male | 109 | 10 | 9.2 | ||||

| Age | <1 year | 38 | 5 | 13.2 | 1.731 | 2 | 0.421 |

| 1-5 year | 132 | 12 | 12 | ||||

| >5 year | 42 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Tick infestation | Yes | 41 | 10 | 24.4 | 14.829 | 1 | 0.001* |

| No | 171 | 9 | 5.3 | ||||

| Antitick treatment | Nil | 32 | 9 | 28.1 | 17.719 | 2 | 0* |

| Within 2 months | 22 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Beyond 2 months | 158 | 10 | 6.2 | ||||

| Outside activity | Nil | 88 | 0 | 0 | 22.543 | 2 | 0* |

| Limited | 50 | 12 | 24 | ||||

| Feral | 74 | 7 | 9.5 |

*p-value is significant at ≤0.05

Tick infestation, anti-tick treatment and outdoor activity of dogs revealed highly significant association (p < 0.01) with risk of H. canis infection. Out of 212 screened dogs, 41 dogs found to be currently ticks infected, whereas, 171 dogs had history of tick infestation. Highest incidence of infection was recorded in dogs with presence of tick (24.4%) rather than previously infested dogs (5.4%). Likewise, dogs without any anti-tick treatment were found to have highest incidence of infection (28.1%), but not a single infection was found in dogs that had undergone anti-tick treatment within 2 months of screening and in dogs that are strictly domesticated without any outdoor activity. Surprisingly, domesticated dogs with limited outdoor activity are found to have significantly higher incidence of hepatozoonosis (24%) surpassing the feral dogs (9.5%).

The hematological parameters of PCR positive dogs for H. canis (both single infection as well as mixed infection) and healthy control group were depicted in Table 5. Hematological values of single and mixed infection groups revealed significantly lower level of mean Hb, platelets, TEC, MCV, MCH, MCHC, PCV level and higher relative neutrophil count with normal TLC level, compared to the healthy control group. Amongst the infected group, dogs with mixed infection were found to have a significantly (P < 0.01) lower mean Hb, platelets, TEC, PCV, MCV, MCH, MCHC level than the groups with single infection while leucocyte parameters remained unaltered.

Table (5):

Haematological changes in H. canis infected dogs

Parameters |

PCR +ve for H. canis (n = 8) |

H. canis with Co-infections (n = 11) |

Control (n = 10) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Haemoglobin (g%) |

9.69 ± 0.29b |

6.92 ± 0.48a |

13.83 ± 0.93c |

0* |

TLCs (Thousands/µl) |

15.03 ± 1.12 |

12.03 ± 1.78 |

11.01 ± 0.42 |

0.125 |

Neutrophil (%) |

73.5 ± 1.03b |

68.63 ± 4.09b |

60.1 ± 1.29a |

0.012* |

Lymphocyte (%) |

23.12 ± 1.12a |

28.18 ± 4.19ab |

33.2 ± 2.22b |

0.110 |

Monocyte (%) |

1.37 ± 0.18 |

1.27 ± 0.19 |

1.7 ± 0.15 |

0.218 |

Eosinophil (%) |

1 ± 0 |

1 ± 0 |

1 ± 0 |

1 |

Basophil (%) |

1 ± 0 |

0.9 ± 0.09 |

1 ± 0 |

0.457 |

Platelets (Thousands/µl) |

118 ± 8.34b |

75 ± 5.68a |

328.5 ± 9.81c |

0* |

Packed Cell Volume (%) |

28.08 ± 1.1b |

20.81 ± 1.49a |

40.9 ± 0.97c |

0* |

TEC (Millions/µl) |

4.97 ± 0.39b |

3.64 ± 1.14a |

6.78 ± 0.19c |

0* |

Mean Cell Volume (fl) |

66.01 ± 0.51b |

63.79 ± 0.77a |

69.4 ± 0.37c |

0* |

Mean Cell Hemoglobin (pg) |

23.01 ± 0.21b |

21.56 ± 0.32a |

23.37 ± 0.41b |

0.001* |

Mean Cell Hemoglobin Concentration (g/dl) |

31.08 ± 0.24b |

29.79 ± 0.22a |

32.36 ± 0.55c |

0* |

*p-value is significant at ≤0.05

Values (mean ± S.E.) that have no common superscript (small letter in a row) vary significantly at p ≤ 0.05.

The identification of 108 ticks collected from 41 tick-harbouring host revealed that 38 dogs were infested with Rhipicephalus species, and only 3 dogs were infested with Haemaphysalis spp., while no mixed tick infestation were detected during screening. A total 101 number of Rhipicephalus and 7 Haemaphysalis ticks were collected from 41 infested dogs. Among the 41 pooled samples, the incidence of protozoa DNA in Rhipicephalus spp. was 34.14% (14/41) (supplementary Figure 4), while the Haemaphysalis spp. were found negative. Out of 14 positive ticks, 8 Rhipicephalus spp. ticks were derived from positive dogs (19.5%), while 6 (14.63%) were derived from uninfected dogs. However, in 01 ( 2.4% ) case, Rhipicephalus ticks collected from H. canis positive dogs had no evidence of H. canis DNA (Table 6).

Table (6):

Prevalence (in %) of Hepatozoon canis in ticks related to the host infection status

| H. canis | Positive ticks | Negative ticks | Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhipicephalus spp. | Haemaphysalis spp. | Rhipicephalus spp. | Haemaphysalis spp. | Pearson Chi-Square value | p-value | |

| Positive Dogs | 08 (19.5% | 0 | 01 (2.4%) | 01 (2.4%) | 42.65 | 0* |

| Negative Dogs | 06 (14.63%) | 0 | 23 (56.09%) | 02 (4.87%) | ||

| Total | 14 (34.14%) | 0 | 24 (58.53%) | 03 (7.3%) | ||

*p-value is significant at ≤0.05

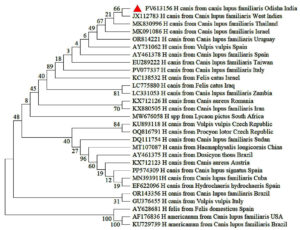

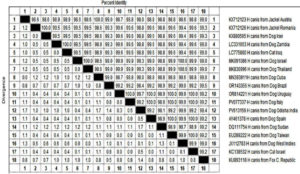

The phylogenetic analysis using a 737 bp fragment of the partial 18S rRNA gene of H. canis retrieved from the NCBI record revealed that nucleotide sequence from Odisha isolate was clustered in one major clade with several mini subclades and was closely related to the sequences of H. canis, isolated from dogs of West Indies, Thailand and Israel (GenBank: JX112783, MK830996 and MK091086 respectively) with exclusion of the clade containing other species of Hepatozoon including H. felis and H. americanum (Figure 2). The nucleotide sequence identity study revealed 98%-100% similarity with other global isolates of H. canis, included in this study with the highest divergence of 1.7% between H. canis isolates from Sudan (DQ111754) and Odisha (PV613156) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis of H. canis based on partial sequence of 18S rRNA gene. Evolutionary analysis was conducted on 500 bootstrap replications using maximum likelihood method. Sequences are presented by GenBank accession number, pathogen species, host and country of origin

This researchprovides the first molecular confirmation of Hepatozoon canis from dogs and vector ticks in Odisha along with a systematic epidemiological approach and evaluation of hematological alterations in affected dogs with hepatozoonosis and concurrent infections (mostly A. platys infections).

In the present study, only 1.4% dogs were microscopically positive, whereas prevalence of hepatozoonosis detected by real-time PCR and conventional multiplex PCR were 9% and 7.5% respectively depicting their higher sensitivity. Though, detection of capsular gamonts in blood films or microschizonts with a distinct “wheel-spoke” shape in bone marrow, spleen or lymph node tissue sections through microscopy are labeled as the ‘gold-standard’ test for diagnosis of hepatozoonosis, still it lacks reliability due to its inability to detect infections and co-infections in carrier animals as well as during subclinical and latent infection in diseased animal.25,26 On the other hand, PCR assays have been proven to be highly efficient in diagnostic performance owing to their higher specificity and sensitivity in diagnosis of ongoing infection.27 Multiplex PCR assays provide the benefit of detecting multiple parasitic DNA targets simultaneously within a single reaction tube.8 However, real-time PCR is considered more promising than conventional PCR and sequencing techniques for diagnosing and monitoring various diseases. This is because real-time PCR tracks amplicon formation during the reaction, enabling highly sensitive and precise quantification of a particular DNA in samples.28 The detection of H. canis infection in dogs (9%) through molecular methods found herein, Odisha targeting 18S r RNA gene was less than that of global reports recorded in Asia (11.4%-42.9%) Europe (44.67%- 57.8%) North America (47.5%), South America (53.3%),29 However the state average also falls below the prevalence rates of other states of India such as 43.8% in Maharastra, 24% in Ladakh, 25.4% in Punjab and 38% from North eastern states, but higher than those of 6.63% in Tamil Nadu, 4% in Kerala.12-15 Such variation in prevalence may be attributed to factors such as difference in sample size and, sampling strategy (dogs with presence or history of tick infestation).

Due to the continuous progress of molecular diagnostic testing, co-infections of canine tick-borne diseases have been found to be a common global phenomenon30 and this study firmly suggests the same for the dogs of this geographical location. H. canis is often found to be co-infected with other TBPs as the Rhipicephalus ticks harbour and transmits multiple pathogens to healthy dogs upon exposure.31,32 The highest rate of coinfection mostly with A. platys (5.1%) found herein, has been also previously reported in Tamil Nadu as 8.3%,13 however, H. canis was reported to be most commonly coinfected with B. gibsoni in northeast India and Punjab (33% and 4.7%)16,17 and in Delhi, Mumbai and Haryana with E. canis (28%, 36.4% and 7.5%)4,32 Consistent with the other studies, some dogs revealed the clinical sign of canine hepatozoonosis, however, most mono-infected cases were found to be asymptomatic and clinical signs are more prominent in case of mixed infections.11,33

Recent evaluations of risk factors linked to the prevalence of hepatozoonosis showed no significant differences based on season, age, sex, or breed, which is consistent with our observations.5,11,25,34 However, significantly higher prevalence were depicted in non-descript breeds14; terrier breeds,11 and although the highest risk is during summer when tick activity is greatest,34 infections may also be detected in colder months, most likely due to lingering infections from earlier exposures.35

Presence of ticks rather than history of tick infestation was significantly related to H. canis infection similar to previous reports5,12 as the ticks, acts as putative vector for H. canis infection and ingestion of infected ticks may lead to active and ongoing infection depending upon the immune status of the dogs.36 Applying proper tick control strategies, including the use of suitable acaricides and routine grooming, helps lower the risk of occurrence in dogs and absence of treatment significantly increases the risk of infection.37 Although strict in-house domestication was found to have significant role in minimizing the haemoparasitic infections due to minimal tick exposure, still dogs with limited outdoor activity unexpectedly revealed higher prevalence than feral dogs. This might be due to the fact that outdoor activity of pet dogs near vegetation during dusk and dawn increases the chance of tick exposure.38 Although feral dogs have greater exposure to tick vectors and more frequent contact, their immune system appears to be better adapted to hemoparasitic infections than that of owned dogs. The notably higher expression of the granzyme B gene in stray dogs, compared with owned dogs, contributes to the commencement of apoptotic pathways within their immune defense.39 Some authors report that common haematological alterations in H. canis infected dogs with or without concurrent infection; have been anaemia followed by thrombocytopenia that corroborates with our finding.36,40 In most cases, the condition presents as normochromic, normocytic regenerative anemia26; however, reduced hemoglobin concentration and diminished red cell staining suggestive of microcytic hypochromic anaemia, observed in this study, have also been described previously.34,41 The leukocyte count in dogs infected with H. canis is generally normal or elevated.3,36 The anemia and neutrophilia recorded here are likely associated with necrosis and inflammatory changes induced in different organs like liver, spleen and lungs.42 Thrombocytopenia in H. canis infection may result from enhanced sequestration of platelets within the liver or spleen, or from reduced platelet production due to bone marrow hypoplasia.43

In the present study, coinfection of H. canis mostly with A. platys revealed a significant drop in mean Hb, platelets, TEC, PCV, MCV, MCH, MCHC level than single infected dogs suggestive of potential pathogen induced red cell destruction, loss of red cell morphology and poor hemoglobinization. Though hematological alterations in H. canis and A. platys coinfected dogs were not previously reported, however, anemia and cyclic episodes of thrombocytopenia were reported to be a consistent finding of A. platys infection44,45 hence the coinfection with H. canis might have exacerbated the condition.

Similar to earlier finding, Rhipicephalus spp. ticks were found to be the most predominant vector, parasitizing the canine population of Odisha, followed by Haemaphysalis spp.46 Although the Rhipicephalus species (R. sanguineus) ticks are recognized as the most prominent ticks for H. canis, with prevalence of 42.5% in Tamil Nadu, India11 and the primary route of infection is through the ingestion of ticks that contain mature oocysts, still other tick species, namely Haemaphysalis longicornis and Haemaphysalis flava were reported to carry and spread H. canis infections in Japan and Amblyomma ovale tick in Brazil.47,48 However, only Rhipicephalus spp. was found to harbour the pathogen at a prevalence of 34.14% in our study, and Haemaphysalis species were negative for H. canis DNA.

Although in 19.5% instances, the H. canis DNA was found in both ticks and their host, still 14.63% ticks were found positive for the pathogen though collected from uninfected dogs. It may be explained by the fact that there is no evidence that Hepatozoon spp. are transmitted through a blood meal or by salivary secretion from the final tick vector to the vertebrate host. The only confirmed route of infection is through ingestion of an infected tick. Alternatively, since the tick is a three-host species, it may acquire H. canis from other dogs during its larval or nymphal stages.36 Moreover, 2.4% Rhipicephalus spp. ticks found negative though collected from infected dogs as an attachment time of at least 48 hr is necessary to acquire infection.49 Vertical transmission of H. canis infection during early gestation has also been recorded in dogs.50 On the basis of evolutionary tree, the similarity among the geographically distinct global isolates and H. canis Odisha isolates indicates a global spread of the pathogen and its vectors.

The maiden molecular report of H. canis in host and ticks with a lower prevalence rate than other parts of India and abroad may indicate a low circulation of this pathogen in Odisha. Globalization, increased travel of pets, importation of dogs from endemic areas and climate change may be responsible factor for vector distribution of pathogen and introduction of this vector-borne pathogen in this particular geographical area. The vector role of Rhipicephalus spp. ticks were confirmed in this study. The dogs positive for H. canis mostly found to be concurrently infected with A. platys. In dogs with anaemia and thrombocytopenia having presence/history of tick infestation, H. canis infection and/or co-infection should taken into consideration for differential diagnosis of tick-borne pathogens in this area. The evolutionary pattern observed herein may be further investigated by targeting other genes.

Additional file: Figure S1-S4.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the contribution and support of the faculty of Department of Veterinary Medicine, and Teaching Veterinary Clinical Complex for the smooth conduct of this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

MD and SB collected resources. RCP acquired funding. SKS, RCP and SB supervised the study. MP and SRM applied methodology. CM, MD and DKK performed analysis. MP and GRJ performed data curation. MP performed investigation. SRM performed validation. MP wrote the manuscirpt. MD reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and/or in the supplementary files.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (Regd. No. 433/CPCSEA), College of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology, Bhubaneswar vide reference no 833/IEAC dated 7.10.2023.

- Gad B, Samish M, Alekseev E, Aroch I, Shkap V. Transmission of Hepatozoon canis to dogs by naturally-fed or percutaneously-injected Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks. J Parasitol. 2001;87(3):606-611.

Crossref - Baneth G, Samish M, Shkap V. Life cycle of Hepatozoon canis (apicomplexa: adeleorina: hepatozoidae) in the tick rhipicephalus sanguineus and domestic dog (canis familiaris). J Parasitol. 2007;93(2):283-299.

Crossref - Gondim LFP, Kohayagawa A, Alencar NX, Biondo AW, Takahira RK, Franco SRV. Canine hepatozoonosis in Brazil: description of eight naturally occurring cases. Vet Parasitol. 1998;74(2-4):319-323.

Crossref - Chamsai T, Saechin A, Mongkolphan C, Sariya L, Tangsudjai S. Tick-borne pathogens Ehrlichia, Hepatozoon, and Babesiaco-infection in owned dogs in Central Thailand. Front Vet Sci. 2024;2;11:1341254.

Crossref - Abd Rani PAM, Irwin PJ, Coleman JT, Gatne M, Traub, RJ. A survey of canine tick-borne diseases in India. Parasit Vector. 2011;4:141-148 .

Crossref - Kordic SK, Breitschwerdt EB, Hegarty BC, et al. Coinfection with multiple tick-borne pathogens in a walker hound kennel in North Carolina. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(8):2631-2638.

Crossref - Pirata S, Pimpjong K, Vaisusuk K, Chatan W. Molecular detection of Ehrlichia canis, Hepatozoon canis and Babesia canis vogeli in stray dogs in Mahasarakham province, Thailand. Ann Parasitol. 2015;61(3):183-187.

- Kaltenboeck B, Wang C. Advances in real-time PCR: Application to clinical laboratory diagnostics. Adv Clin Chem. 2005;40:219-259.

Crossref - Liu J, Youquan L, Aihong L, et al. Development of a multiplex PCR assay fordetection and discrimination of Theileria annulata and Theileria sergenti in cattle. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(7):2715–2721.

Crossref - Bhusri B, Lekcharoen P, Changbunjong T. First detection and molecular identification of Babesia gibsoni and Hepatozoon canis in an Asiatic wild dog (Cuon alpinus) from Thailand. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2022;17:225-229.

Crossref - Manoj RRS, Iatta R, Latrofa MS, et al. Canine vector-borne pathogens from dogs and ticks from Tamil Nadu, India. Acta Trop. 2020;203:105308.

Crossref - Revathi P, Bharathi VM, Madhanmohan M, Latha RB, Rani VK. Molecular Epidemiology, Characterisation of Hepatozoon canis in Dogs as well as in Ticks and Haemato-biochemical Profile of the Infected Dogs in Chennai. Indian J Anim Res. 2022;59(5):4801.

Crossref - Lakshmanan B, Jose KJ, George A, Usha NP, Devada K. Molecular detection of Hepatozoon canis in dogs from Kerala. J Parasitic Dis. 2018;42(2):287-290.

Crossref - Sarma K, Biala YN, Kumar M, Baneth G. Molecular investigation of vector borne parasitic infections in dogs in Northeast India. Parasite Vector. 2019;12(1):122.

Crossref - Thomas AM, Singh H, Panwar H, Sethi RS, Singh NK. Duplex real time PCR methods for molecular detection and characterization of canine tick borne hemoparasites from Punjab state, India. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49(6):4451-4459.

Crossref - Kottek M, Grieser J, Beck C, Rudolf B, Rubel F. World Map of the Koppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Met and Zool. 2006;15(3):259-263.

Crossref - Walker A, Bouattour A, Camicas J, et al. Ticks of Domestic Animals in Africa: A Guide to Identification of Species. Bioscience Reports, Edinburgh. 2003.

- Soulsby EJL. Helminths, Arthropods and Protozoa of Domesticated Animals, 7th ed. ELBS, Bailliere Tindall, London.1982.

- Juyal PD, Singh NK, Singh H. Diagnostic Veterinary Parasitology: An introduction, 1stEdn New India Publishing Agency, New Delhi. 2013:30-32.

- Tajedin L, Bakhshi H, Faghihi F, Telmadarraiy Z. High infection of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia spp. among tick species collected from different geographical locations of Iran Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2016;6(10):787-792.

Crossref - Kledmanee K, Suwanpakdee S, Krajangwong S, et al. Development of multiplex polymerase chain reaction for detection of Ehrlichia canis, Babesia spp. and Hepatozoon canis in canine blood. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 2009;40:35-39.

- Sathish G, Subapriya S, Parthiban M, Vairamuthu S. Detection of canine blood parasites by a multiplex PCR. J Vet Parasitol. 2021;35(1):64-68.

Crossref - Kaur N, Singh H, Sharma P, Singh NK, Kashyap N, Singh NK. Development and application of multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of Babesia vogeli, Ehrlichia canis and Hepatozoon canis in dogs. Acta Tropica. 2020;212:105713.

Crossref - Kumar S, Stecher G, Suleski M, Sanderford M, Sharma S, Tamura K. Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol Biol Evol. 2024;41(12):msae263.

Crossref - Singh K, Singh H, Singh NK, Kashyap N, Sood NK, Rath SS. Molecular prevalence, risk factors assessment and haemato-biochemical alterations in hepatozoonosis in dogs from Punjab, India. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;55:53-58.

Crossref - Hasani SJ, Rakhshanpour A, Enferadi A, Sarani S, Samiei A, Esmaeilnejad B. A review of Hepatozoonosis caused by Hepatozoon canis in dogs. J Parasitic Dis. 2024;48(3):424-438.

Crossref - Hegab AA, Omar HM, Abuowarda M, Ghattas SG, Mahmoud NE, Fahmy MM. Screening and phylogenetic characterization of tick-borne pathogens in a population of dogs and associated ticks in Egypt. Parasit Vectors. 2022;15(1):222.

Crossref - Padmaja M, Singh H, Panwar H, Singh NK, Singh NK. Development and validation of multiplex SYBR Green real-time PCR assays for detection and molecular surveillance of four tick-borne canine haemoparasites. Ticks Tick Born Dis. 2022;13(3):101937.

Crossref - Erol U, ltay K, Atas AD, Ozkhan E, Sahin OF. Molecular Prevalence of Canine Hepatozoonosis in Owned-Dogs in Central Part of Turkey. Isr J Vet Med. 2021;76(2):71-76.

- Shaw SE, Day MJ, Birtles RJ, Breitschwerdt EB. Tick-borne infectious diseases of dogs. Trends in Parasitol. 2001;17(2):74-80.

Crossref - Yabsley MJ, McKibben J, Macpherson CN, et al. Prevalence of Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma platys, Babesia canis vogeli, Hepatozoon canis, Bartonella vinsoniiberkhoffii, and Rickettsia spp. in dogs from Grenada. Vet Parasitol. 2008;151(2-4):279-285.

Crossref - Bhagwan J, Singh Y, Jhambh R. Chaudhari M, Kumar P. Molecular and microscopic detection of haemoprotozoan diseases in dogs from Haryana, India. Parasitol Res.2024;123:354.

Crossref - Pasa S, Voyvoda H, Karagenc T, Atasoy A, Gazyagci S. Failure of combination therapy with imidocarb dipropionate and toltrazuril to clear Hepatozoon canis infection in dogs. Parasitol Res. 2011;109(3):919-26.

Crossref - Bhagwan J, Singh Y, Jhambh R, et al. Molecular Characterization, Haemato-Biochemical Profile and Risk Factor of Hepatozoon Canis Infection in Dogs From, Haryana, India. Acta Parasitol. 2025;70(4):169.

Crossref - Baneth G, Aroch I, Presentey B. Hepatozoon canis infection in a litter of dalmatian dogs. Vet Parasitol. 1997;70(1-3):201-206.

Crossref - Baneth G. Perspectives on canine and feline hepatozoonosis. Vet Parasitol. 2011;181(Suppl 1):3-11.

Crossref - Dekeyser MA. Acaricide mode of action. Pest Manag Sci Former Pestic Sci. 2005;61(2):103-110.

Crossref - Noden BH, Loss, SR, Maichak C, Williams F. Risk of encountering ticks and tick-borne pathogens in a rapidly growing metropolitan area in the US Great Plains. Ticks Tick Born Dis. 2007;8(1):119-124.

Crossref - Temizkan MC, Sonmez G. Are owned dogs or stray dogs more prepared to diseases? A comparative study of immune system gene expression of perforin and granzymes. Acta Vet Hung. 2022;70(1):24-29.

Crossref - Zoaktafi E, Sharifiyazdi H, Derakhshandeh N, Bakhshaei-Shahrbabaki F. Detection of Hepatozoon spp. in dogs in Shiraz, southern Iran and its effects on the hematological alterations. Mol Biol Res Commun. 2023;12(2):87-94.

Crossref - Ivanov A, Kanakov D. First case of canine hepatozoonosis in Bulgaria. Bulg J Vet Med. 2003;6(1):43-46.

- Gaunt PS, Gaunt SD, Craig TM. Extreme neutrophilic leukocytosis in a dog with hepatozoonosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;182:409-410.

Crossref - Tuna GE, Bakrc S, Uluta B. Evaluation of clinical and haematological findings of mono-and co-infection with Hepatozoon canis in dogs. Anim Health Prod Hygiene. 2020;9(1):696-702.

- Dyachenko V, Pantche, N, Balzer HJ, Meyersen A, Straubinger RK. First case of Anaplasma platys infection in a dog from Croatia. Parasit Vector. 2012;5(1):49.

Crossref - Eddlestone SM, Gaunt SD, Neer TM, et al. PCR detection of Anaplasma platys in blood and tissue of dogs during acute phase of experimental infection Exp Parasitol. 2007;115(2):205-210.

Crossref - Sahu A, Mohanty B, Panda MR, Sardar KK, Dehuri M. Prevalence of tick infestation in dogs in and around Bhubaneswar. Vet World. 2013;6(12):982-985.

Crossref - Murata T, Inoue M, Taura Y, Nakama S, Abe H, Fujisaki K. Detection of Hepatozoon canis oocyst from ticks collected from the infected dogs. J Vet Med Sci. 1995;57(1):111-112.

Crossref - Forlano M, Scofield A, Elisei C., Fernandes KR, Ewing SA, Massard CL. Diagnosis of Hepatozoon spp. in Amblyomma ovale and its experimental transmission in domestic dogs in Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2005;134(1-2):1-7.

Crossref - Kidd L, Breitschwerdt E. Transmission times and prevention of tick-borne diseases in dogs. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 2003;25(10):742-751.

- Murata T, Inoue M, Tateyama S, Taura Y, Nakama S. Vertical transmission of Hepatozoon canis in dogs. J Vet Med Sci. 1993;55(5):867-868.

Crossref - Chen G, Severo MS, Sakhon OS, et al. Anaplasma phagocytophilum dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase1 affects host-derived immunopathology during microbial colonization. Infect Immun. 2012;80(9): 3194-3205.

Crossref - Free World Maps. Net https://www.freeworldmaps.net/asia/india/odisha. Accessed on 28 October 2025

- D-maps.com. https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=272235&lang=en. Accessed on 28 October 2025

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.