ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

The antagonistic activity of Aspergillus piperis against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. fabae (FOF) and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum were examined and showed multiple signs of hyphal interactions. Microscopic examination of contact regions among A. piperis and each pathogen revealed distinct enzymatic lysis of pathogenic hyphal cell walls. Therefore, it is important to estimate the lytic enzyme activity of A. piperis. Extracellular lytic enzymes are important offensive forces for A. piperis as a biological control agent. Chitinase, phospholipase, and protease recorded relatively high activity from a culture age of 10 days (82.3, 42.4, and 6.2 U/ml, respectively). Enzymatic persistence was measured at room temperature, recording relatively long periods, saving 54%, 46%, and 21% of their activity, respectively. The cytotoxicity of the crude culture filtrate of A. piperis was examined in MCF7 and WI38 human cell lines. The cell viability (IC50) value of the fungal filtrate was estimated after 24 h and 48 h. The results revealed that IC50 values against the MCF7 cell line were inoperative after 24 h and were recorded 80 μg/ml after 48 h. In contrast, IC50 values against the WI38 cell line were 85.69 and 69.8 μg/ml after 24 and 48 h, respectively.

Aspergillus piperis, Sclerotinia, Fusarium, Lytic enzymes, cytotoxicity, Antagonism

Phytopathogenic fungi are considered the most common and distributed causal agents of plant diseases. Their unique reproductive structures, such as spores, sclerotia, and rhizomorphs, are responsible for widespread fungal pathogens and plant fungal diseases.1,2 In particular, under favorable environmental conditions, fungi attack their host plants for nourishment. They invade the plant body via stomata, wounds, or direct penetration of the plant epidermis.2,3 The use of biological control agents, including antagonistic fungi, is considered a safe and eco-friendly method to control plant fungal diseases.4,5

Notably, antagonistic microorganisms use diverse mechanisms, including lytic enzymes, toward phytopathogenic fungi.6,7 Several enzymatic activities have been attributed to the famous antagonistic fungus Trichoderma against many phytopathogenic fungi. For example, the extracellular enzyme chitinase and oxidative enzymes, polyphenol oxidase, peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase defense enzyme, and β-1,3-glucanase.8-11 Recently, researchers interested in mycology and plant pathology have focused their studies on new antagonistic fungi. In the last few years, Aspergillus piperis was one of the fungal species discovered to have successful antagonistic activity against some phytopathogenic fungi.12

Accordingly, the present study aimed to investigate the antagonistic activity of A. piperis using lytic enzymes such as chitinase, phospholipase, and protease in suppressing some phytopathogenic fungi in vitro. In addition, we tested the cytotoxic activity of the culture filtrate of A. piperis against some human cell lines.

Test fungi

The antagonistic fungus Aspergillus piperis (AUMMC No.9043) was procured from AUMMC (Center of Prof. A.H. Moubasher for Mycological Sciences, Assuite University, Assuite, Egypt). S. sclerotiorum was isolated from the diseased stems and pods of Phaseolus vulgaris. Mature sclerotia of S. sclerotiorum were picked from the infected plant parts, surface sterilized with absolute ethanol for 2 min, and then washed twice with sterilized distilled water for 10 min. The sterilized sclerotia were crushed and transferred to PDA plates supplemented with chloramphenicol as an antibacterial agent. The inoculated plates were incubated at 23°C ± 2 for ten days. Pure cultures from the isolated fungus were examined and identified morphologically according to.13-15 The used strain of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. fabae (FOF) was vouchsafed by the Faculty of Agriculture, Mansoura University, Egypt, who isolated it from diseased faba bean plants. All fungal genera were subcultured using a PDA medium supplemented with the antibiotic chloramphenicol to prevent bacterial contamination.

Antagonistic test

A modified dual culture method16 was used to study the antagonistic activity of A. piperis, and its ability to inhibit the test phytopathogenic fungi. On PDA plates of 90 mm diameter, seven-day plugs (10 mm in diameter) of the tested antagonist with one pathogen were inoculated at the same distance from the center of the plate. Plates FOF were incubated at 26 ± 2°C, while plates of S. sclerotiorum were incubated at 23 ± 2°C in the dark for 12 days. Plates inoculated only with the pathogen were used as controls, and each treatment was performed in triplicates. Dual Petri plates were examined and photographed every day to estimate the hyphal interactions in the contact areas of the antagonist/pathogen. After the incubation, the mean diameter of the pathogens in the dual cultures was compared to that in control. Then, the percentage growth inhibition (%) was calculated according to the formula given in17,18: I= (C – T)/C × 100, where I=percentage inhibition of fungal mycelial growth with respect to control, C = growth in control, and T = growth in treatment.

Slide culture test

The hyphal interactions between A. piperis and the test phytopathogenic fungi were tested using the slide culture method according to a modified method of.19 A clean slide was placed in a Petri dish and sterilized in an autoclave at 121°C, 1.5 atm. for about 15 min. Under sterile conditions, a small amount of autoclaved melted PDA was spread over the slide to make a thin PDA film on the slide. Fungal discs (3 mm) of each pathogen and antagonist were separately paired on a slide 3 cm apart on the PDA surface. Plates of FOF were incubated at 26 ± 2°C, while plates of S. sclerotiorum were incubated at 23 ± 2°C in the dark for seven days. The meeting area among A. piperis and each of the test phytopathogenic fungi was observed microscopically by staining with lactophenol and cotton blue. The presence of mycelial penetration, coiling, lysis or cell wall disintegration were recorded and photographed. For more detection and investigation of hyphal interactions, a print from the contact hyphal region was taken using adhesive tape and then placed on another clean slide and mounted with methylene blue. Then, all the prepared slides were investigated using a binocular biological light microscope (Model: XSZ-107BN) at high power (400×) and oil immersion (1000×) and photographed.

Enzymatic assay in culture filtrate of A. piperis

Chitinase assay

Fungal chitinase activity was measured according to the following procedure: Colloidal chitin was prepared as a substratum to induce chitinase enzyme by the test fungus. In a conical flake, 100 g of shrimp shell chitin was slowly added to 1.75 L of 3 M HCl and mixed by a magnetic stirrer for 3 h. Then, the mixture was diluted to 10 L with distilled water and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min. A dense white precipitate was collected, weighed, and washed with distilled water until the pH reached 5.5, resulting in a colloidal chitin suspension of 10% concentration. This suspension was stored at 4°C for further use, according to a technique modified from.20

The culture of A. piperis was prepared using a minimal salt medium composed of (g/L) (NH4)2SO4, 1; KH2PO4, 0.2; K2HPO4, 1.6; MgSO4.7H2O, 0.2; NaCl, 0.1; FeSO4.7H2O, 0.01; and CaCl2.2H2O, 0.02.21 The broth medium was autoclaved, inoculated with 0.5 cm fresh culture discs, and incubated at 27°C in a shaking incubator at 80 rpm for 5, 10, and 15 days. Fungal cultures of different ages were filtered, and the filtrates were mixed separately with 1:1 volume of the previously prepared colloidal chitin suspension and incubated at 27°C in a shaking incubator at 80 rpm for 2, 6, 12, 18, 24, and 48 h. The persistence of chitinase was evaluated by measuring its activity after different incubation periods.

The extracellular chitinase activity of the previously cultivated A. piperis was measured and calculated as the percentage of turbidity reduction of the chitin-enzyme mixture at 510 nm against a standard curve of known chitin concentrations; one enzyme unit was defined as the amount of enzyme that reduced the chitin turbidity by 1%.22

Phospholipase assay

Fungal phospholipase activity was measured as follows:

Sabouraud’s dextrose medium (peptone, 10 g/L; glucose, 10 g/L),23 supplemented with egg yolk at a final concentration of 5%, was used to measure the phospholipase activity of A. piperis. Egg yolk is considered a rich source of phosphatidylcholine as a phospholipid source for the induction of fungal phospholipase production. Three replicate cultures were incubated at 27°C for 5, 10, and 15 h. Extracellular phospholipase activity was measured for different ages of the test fungal cultures, and the persistence of the produced enzyme was calculated by reading the absorbance of released fatty acids in the filtrate after regular storage intervals (2, 6, 12, 18, 24, and 48 h) at 546 nm. Concentrations of fatty acids were determined using a standard curve of oleic acid absorbance at known concentrations. One enzyme unit was defined as the amount of phospholipase enzyme that released 1 mM of fatty acids in 1 min.24

Protease assay

Fungal protease activity was measured as follows:

The proteolytic activity of A. piperis was induced by cultivating 0.5 cm fungal discs on a sterilized protease production medium composed of KH2PO4 (0.1%), K2HPO4 (0.1%), MgSO4 (0.02%), glucose (2%), yeast extract (1%), and casein (1%), with pH adjusted to 7. The incubation process was performed in a shaking incubator at 80 rpm and 27°C for 5, 10, and 15 days.25

Protease activity was estimated in the fungal culture filtrate by a technique modified from26 after regular storage intervals (2, 6, 12, 18, 24, and 48 h) as follows: 0.5 ml of each crude enzyme culture filtrate was mixed with 0.5 ml of casein solution (1% casein in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6). All the reaction mixtures (different culture ages and different storage intervals) were incubated at 30°C for 30 min in a shaking incubator at 80 rpm. Then, 1 ml Folin’s reagent was added to each mixture separately, giving a blue color with amino acids and peptide fragments from the casein digestion. The released products were quantified by measuring their absorbance at 660 nm against a standard curve of known tyrosine concentrations. All measurements were performed in triplicate against a blank. One enzyme unit was defined as the amount of enzyme that produces 1 µM tyrosine per minute under the assay conditions. All results were tabulated to evaluate the protease activity on casein for the test fungus at different culture ages and detect its persistence after different storage intervals.

Cell viability test

This study aimed to investigate the toxic effects of A. piperis culture filtrates on normal and cancer human cell lines. The culture filtrate was prepared using potato dextrose (PDL) broth medium.27 The culture of A. piperis on PDL was grown for 20 days at 28°C, before removing the mycelial mat by filtration through Whatman No.1 filter paper. Then, a toxicity test of the crude culture filtrate was performed according to the method adopted by.28 The normal human cell line (WI38) and breast cancer cell line (MCF7) were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 before use. The medium was then replaced with fresh RPMI-10% FBS. The cells were maintained by subculturing them after reaching an acceptable confluence. The cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates at a concentration of 1 × 104 cells/ml and incubated for 24 h under standard conditions to reach exponential growth. The cells were treated with different concentrations of fungal filtrate (0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 μg/ml), where 0 μg/ml was considered the control. At the end of the incubation time (24 and 48 h), the medium was removed, and 5 mg/ml of MTT reagent (yellow color) was added to each plate and incubated for 3–4 h. This reagent was reduced inside the mitochondria of viable cells to violet-colored formazan crystals. The formed formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 μg acidified isopropanol and read at 630 nm using an ELISA microplate reader (Bio-RAD microplate reader, Japan). Each concentration was repeated in triplicates. The cell viability was calculated using the following equation:

Cell viability (%) = (Abs test/ Abs control) × 100, where Abs is absorbance. Calculations of viable cell percentage were considered an indication of cell toxicity due to fungal filtrate.

Statistical analyses

The obtained results were statistically analyzed using the mean, standard deviation (SD), and analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the online free source, Free Statistics Calculators version 4.0. Statistical significance was set at P <0.001.

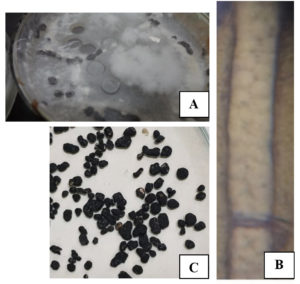

Morphological and microscopic examination of the isolated pathogenic fungus from P. vulgaris plants (Fig. 1) on pure culture plates indicated that the tested fungus was S. sclerotiorum (Fig. 2). The plates of S. sclerotiorum were recognized by the formation of large sclerotia (2 × 2 mm to 5.5 × 3.5 mm). The tested sclerotia are sub-globose to ellipsoidal in shape, rigid, white at first, and then turned black. Exudate droplets formed on their surfaces are distinct features of S. sclerotiorum. Examination of the hyphae microscopically revealed the presence of granules inside the hyphal cells. All these features are specialized to S. sclerotiorum from other species of Sclerotinia.

Fig. 2. Morphological and microscopic description of S. sclerotiorum; culture plate (A), hyphal cell (B, 1000x) and Sclerotia (C, 4x)

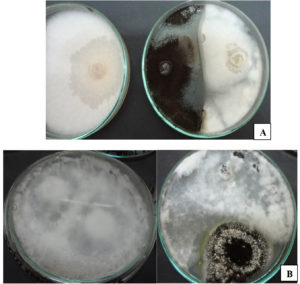

Antagonistic activity of A. piperis in dual culture plates

The paired plates between A. piperis and the phytopathogens used showed that A. piperis successfully affected the growth of the test phytopathogens compared to the control plates. Fig. 3 shows the antagonistic effect of A. piperis against the phytopathogenic fungi tested in dual culture plates. The percentages of inhibition against FOF and S. sclerotiorum were 52.77% and 48.27%, respectively. The hyphae of A. piperis exhibited faster growth than the test pathogens, which gave it a great chance to invade the hyphae of the test phytopathogens.

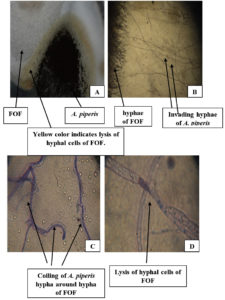

The presence of yellow color in the contact area between hyphae of A. piperis and FOF indicated breaking of its hyphal cells, releasing their internal metabolites (Fig. 4A). Moreover, examination of slide culture illustrated the fast growth of A. piperis hyphae towards FOF (Fig. 4B), which then coiled around them (Fig. 4C), causing lysis to their walls by extracellular lytic enzymes of A. piperis (Fig. 4D).

Although the S. sclerotiorum isolate was considered ferocious, where it spread quickly and recorded the lowest inhibition percentage in the paired plates, microscopic examination indicated a more potent effect of A. piperis. The antagonistic activity of A. piperis against S. sclerotiorum is shown in Fig. 5 using mycoparasitic interactions and extracellular lytic enzymes that destroy the hyphal cells of S. sclerotiorum.

Enzymatic assay in culture filtrate of A. piperis

Extracellular enzymes are considered very effective offensive forces for A. piperis, facilitating its invasion into other pathogenic fungal hyphae as a promising biological control agent for plant and post-harvest diseases. A. piperis chitinase activity was measured after different culture ages and after different storage periods for each culture age; as it rises from 40.7 U/ml after five days to 82.3 U/ml after ten days as the best culture age for enzyme harvest, as shown in Table 1. At this age, the enzyme possessed long persistence on storage at room temperature, as chitinase activity only decreased to 61% after 18 h and 54% after 24 h, and still saved 51% of its activity after 48 h.

Phospholipase is considered an important extracellular enzyme tool for the biological control of A. piperis. It also possessed the highest activity after ten days of culture age (42.4 U/ml). It possessed a relatively long persistence at room temperature, as it decreased only to 57% after 18 h, 46% after 24 h, and still saved 41% of its activity after 48 h, as listed in Table 1.

Protease was found to be another important tool for the biological control of A. piperis. The highest activity was recorded after a culture age of 10 days (6.2 U/ml). It possessed less persistence in storage, as its activity decreased to 31% after 18 h and 21% after 24 h, as shown in Table 1.

Table (1):

Chitinase, Phospholipase and Protease activity and persistence for A. piperis.

| Age of culture (days) |

Enzyme parameters | Target enzyme | Storage intervals (hours) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 48 | |||

| 5 | Enzyme activity (U/ml) | Chitinase | 40.7 | 30.5 | 26.1 | 23.2 | 15.9 | 10.6 |

| Phospholipase | 26.5 | 17.5 | 13.5 | 11.7 | 8.5 | 4.5 | ||

| Protease | 8.7 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 1.6 | ||

| Enzyme persistence (%) | Chitinase | 100 | 75 | 64 | 57 | 39 | 26 | |

| Phospholipase | 100 | 66 | 51 | 44 | 32 | 17 | ||

| Protease | 100 | 77 | 59 | 41 | 28 | 18 | ||

| 10 | Enzyme activity (U/ml) | Chitinase | 82.3 | 68.3 | 63.4 | 50.2 | 44.4 | 41.9 |

| Phospholipase | 42.4 | 33.1 | 27.1 | 24.2 | 19.5 | 17.4 | ||

| Protease | 6.2 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.9 | ||

| Enzyme persistence (%) | Chitinase | 100 | 83 | 77 | 61 | 54 | 51 | |

| Phospholipase | 100 | 78 | 64 | 57 | 46 | 41 | ||

| Protease | 100 | 63 | 46 | 31 | 21 | 14 | ||

| 15 | Enzyme activity (U/ml) | Chitinase | 78.6 | 56.6 | 46.4 | 33.8 | 17.3 | 14.9 |

| Phospholipase | 38.7 | 31.7 | 27.5 | 24.8 | 20.1 | 18.2 | ||

| Protease | 4.8 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.3 | ||

| Enzyme persistence (%) | Chitinase | 100 | 72 | 59 | 43 | 22 | 19 | |

| Phospholipase | 100 | 82 | 71 | 64 | 52 | 47 | ||

| Protease | 100 | 43 | 28 | 18 | 12 | 7 | ||

Cell viability test

The cytotoxic activity of different concentrations of fungal filtrate of A. piperis was evaluated against WI38 and MCF7 human cell lines using the MTT assay by calculating the percentage of viable cells after the incubation period. Half of the WI38 cell line was killed at IC50 values of 85.69 and 69.8 µg/ml after 24 and 48 h, respectively (Table 2). These results indicate that the fungal filtrate used will affect the normal human cells at these concentrations if used on consumed plant parts through the biocontrol process of plant diseases. Therefore, these IC50 values must be considered when using A. piperis to control plant diseases for the safety of human beings. On the other hand, the concentrations of the fungal filtrate did not affect the MCF7 cancer cell line after 24 h, but the IC50 value was 80 µg/ml after 48 h (Table 3).

Table (2):

Cell viability of normal cell line (WI38) after 24 and 48 h at different concentrations of cultural filtrate of A. piperis.

| Conc. (μg/ml) |

Abs. after 24 h (Mean ± SD) |

IC50 (μg/ml) |

Abs. after 48 h (Mean ± SD) |

IC50 (μg/ml) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2.46 ± 0.047 | 85.69 | 2.86 ± 0.124 | 69.8 | |

| 20 | 2.7 ± 0.08 | 3.22 ± 0.111 | |||

| 40 | 2.43 ± 0.021 | 2.13 ± 0.169 | |||

| 60 | 2.19 ± 0.029 | 2.216 ± 0.062 | |||

| 80 | 1.95 ± 0.049 | 0.603 ± 0.026 | |||

| 100 | 0.723 ± 0.88 | 0.54 ± 0.008 | |||

| ANOVA | F-value | 11.539 | 375.361 | ||

| P- value | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | |||

Abs.: Absorbance. SD: Standard Deviation. *: Significant at P < 0.001.

Table (3):

Cell viability of breast cancer cell line (MCF7) after 24 and 48 h at different concentrations of cultural filtrate of A. piperis.

| Conc. (μg/ml) |

Abs. after 24 h (Mean ± SD) |

IC50 (μg/ml) |

Abs. after 48 h (Mean ± SD) |

IC50 (μg/ml) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.4 ± 0.08 | No effect at used concentrations | 2.83 ± 0.23 | 80 | |

| 20 | 1.33 ± 0.047 | 2.55 ± 0.324 | |||

| 40 | 1.31 ± 0.08 | 2.413 ± 0.08 | |||

| 60 | 1.45 ± 0.03 | 1.6 ± 0 | |||

| 80 | 1.4 ± 0 | 1.466 ± 0.047 | |||

| 100 | 1.35 ± 0.04 | 1.226 ± 0.089 | |||

| ANOVA | F-value | 163.198 | 45.514 | ||

| P- value | 0.000 * | 0.000 * | |||

Abs.: Absorbance. SD: Standard Deviation. *: Significant at P < 0.001.

Other studies supported the morphological characteristics for identification of the isolated pathogenic fungus S. sclerotiorum, such as.12,15,29

On the other hand, the antagonistic activity of A. piperis against the phytopathogens agreed with the results of other researchers, where30 investigated the successful biocontrol of A. solani by several antagonists, including Aspergillus niger. In addition, the findings in this study of biocontrol of FOF using A. piperis were per the results of31, who recorded the biocontrol of tomato plant diseases caused by Fusarium solani using the glucose oxidase enzyme of Aspergillus tubingensis, a member of the Aspergillus niger group. Other researchers32 reported the biocontrol of Fusarium sambucinum, the causal agent of Fusarium dry rot of potato tubers, by several Aspergillus species, including A. niger. Moreover, our results against S. sclerotiorum were per a recent study33 that confirmed the antifungal activity of both A. japonicus and A. niger against S. sclerotiorum by suppressing its sclerotia formation.

Biological control fungal agents can use extracellular hydrolytic enzymes to attack plant pathogens. Among the biocontrol agents, the chitinolytic ones have been successfully used to control several pathogenic fungi34; reported that Paecilomyces sp. has significantly greater colloidal chitin degradation. In addition, an important application for the chitinolytic activity for marine biowaste management, extracted from A. terreus, was reported by other researchers.35 Antifungal enzymes are extensively produced by Trichoderma atroviride.36

Phospholipase B is also related to virulence in many pathogenic fungi, such as Candida albicans and A. fumigatus.37 In addition, approximately 85% of phospholipase B activity in Cryptococcus neoformans is cell-associated.38 In the case of protease enzymes39, monitored the production of protease enzymes from paddy field soil fungal isolates obtained from Mannargudi, Tamil Nadu, where A. flavus and A. niger showed the highest extracellular protease activity. In contrast, Cladosporium sp. is considered a potent protease producer for commercial production and applications, rather than standard A. flavus isolates.25

The present study concluded that A. piperis successfully controlled the test pathogens (FOF and S. sclerotiorum) in a dual culture test. The antagonistic fungus used several mycoparasitic mechanisms to attack pathogenic hyphae. These mechanisms were emphasized in hyper-parasitism by the coiling of A. piperis hyphae around the pathogenic hyphae and enzymatic lysis of pathogenic hyphae. Extracellular enzymes such as chitinase, phospholipase, and protease of A. piperis were measured as offensive forces for A. piperis as a biological control agent. These enzymes show high activity and persistence. The crude culture filtrate of A. piperis showed various toxic values against breast cancer (MCF7) and normal (WI38) human cell lines. Promising results regarding the antagonistic activity of A. piperis against some phytopathogenic fungi were obtained from this study. However, more studies are needed for its use as a biocontrol agent in the field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

SE isolated, sub-cultured and identified the used fungi, performed the bio-controlling experiments, microscopic examination, and cytotoxicity test, analysed the obtained data, and shared with her co-author in editing the manuscript. AE performed the enzymatic activity and persistence experiments and shared in editing the manuscript.

FUNDING

None.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- El-Debaiky SAE-K. Biological Control of Some Plant Diseases Using Different Antagonists Including Fungi and Rhizobacteria. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Stress Management: Springer. 2019:47-64.

Crossref - Leonberger K, Jackson K, Smith R, Ward G. N. Plant diseases Kentucky Master Gardener Manual. University of Kentucky UKnowledge, Kentucky, USA Agriculture and Natural Resources Publications; 2016.

- Fry WE. Principles of plant disease management. New YorK and London: Academic Press; 2012.

- Tewari L, Bhanu C. Screening of various substrates for sporulation and mass multiplication of bio-control agent Trichoderma harzianum through solid state fermentation. Indian Phytopathology. 2003;56:476-478.

- Barakat R, Al-Masri MI. Biological control of gray mold disease (Botrytis cinerea) on tomato and bean plants by using local isolates of Trichoderma harzianum. Dirasat, Agri Sci. 2005;32:145-156.

- Carmona-Hernandez S, Reyes-Perez JJ, Chiquito-Contreras RG, Rincon-Enriquez G, Cerdan-Cabrera CR, Hernandez-Montiel LG. Biocontrol of postharvest fruit fungal diseases by bacterial antagonists: A review. Agronomy. 2019;9(3):121.

Crossref - Camlica E, Tozlu E. Biological control of Alternaria solani in tomato. Fresenius Environ Bull. 2019;28:7092-7100.

- Montealegre J, Valderrama L, Sanchez S, Herrera R, Besoain X, Perez LM. Biological control of Rhizoctonia solani in tomatoes with Trichoderma harzianum mutants. Electron J Biotechnol. 2010;13:1-11.

Crossref - Chowdappa P, Kumar NB, Madhura S, et al. Emergence of 13_ A 2 Blue Lineage of Phytophthora infestans was Responsible for Severe Outbreaks of Late Blight on Tomato in South-West India. Journal of Phytopathology. 2013;161(1):49-58.

Crossref - Chohan S, Perveen R, Abid M, Naz MS, Akram N. Morpho-physiological Studies Management and Screening of Tomato Germplasm against Alternaria solani the Causal Agent of Tomato Early Blight. Int J Agric Biol. 2015;17(1):111-118.

- EL Badry A, El Debaiky S. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of Some Enzymes of Trichoderma harzianum Immobilized on Polyester Cloth Films on The Disease Incidence of Postharvest Black Mold Disease of Tomatoes. Egy J Microbiol. 2018;53(1):23-35.

Crossref - El-Debaiky SA. Antagonistic studies and hyphal interactions of the new antagonist Aspergillus piperis against some phytopathogenic fungi in vitro in comparison with Trichoderma harzianum. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2017;113:135-143.

Crossref - Garg H, Kohn LM, Andrew M, Li H, Sivasithamparam K, Barbetti M. Pathogenicity of morphologically different isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum with Brassica napus and B. juncea genotypes. European Journal of Plant Pathology. 2010;126:305-315.

Crossref - Kohn LM. A monographic revision of the genus Sclerotinia. Mycotaxon. 1979;9:365-444.

- Ekins M, Aitken E, Goulter K. Identification of Sclerotinia species. Australasian Plant Pathology. 2005;34:549-555.

Crossref - Pellan L, Durand N, Martinez V, Fontana A, Schorr-Galindo S, Strub C. Commercial biocontrol agents reveal contrasting comportments against two mycotoxigenic fungi in cereals: Fusarium Graminearum and Fusarium Verticillioides. Toxins. 2020;12(3):152.

Crossref - Jayasinghe C, Wijesundera R. In vitro evaluation of fungicides against clove isolate of Cylindrocladium quinqueseptatum in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Pest Management. 1995;41:219-223.

Crossref - Vincent JM. Distortion of fungal hyphae in the presence of certain inhibitors. Nature. 1947;159:850.

Crossref - Harris JL. Modified method for fungal slide culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24(3):460-461.

https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.24.3.460-461.1986 - Roberts WK, Selitrennikoff CP. Plant and bacterial chitinases differ in antifungal activity. Microbiol. 1988;134(1):169-176.

Crossref - Furukawa K, Matsumura F, Tonomura K. Alcaligenes and Acinetobacter strains capable of degrading polychlorinated biphenyls. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 1978;42(3):543-548.

Crossref - Tronsmo A, Harman GE. Detection and quantification of N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase, chitobiosidase, and endochitinase in solutions and on gels. Analytical Biochemistry 1993;208(1):74-79.

Crossref - Booth C. Methods in microbiology: Academic Press; New York. 1971.

- Kadir T, Gumru B, Uygun-Can B. Phospholipase activity of Candida albicans isolates from patients with denture stomatitis: the influence of chlorhexidine gluconate on phospholipase production. Archives of Oral Biology 2007;52(7):691-696.

Crossref - Saxena J, Choudhary N, Gupta P, Sharma M, Singh A. Isolation and characterization of neutral proteases producing soil fungus Cladosporium sp PAB2014 Strain FGCC/BLS2: Process optimization for improved enzyme production. J Sci Ind Res. 2017;76:707-713.

- Kamath P, Subrahmanyam V, Rao JV, Raj PV. Optimization of cultural conditions for protease production by a fungal species. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2010;72:161-166.

Crossref - El-Debaiky S. Evaluation and Detection of Ochratoxins and Aflatoxins of Aspergillus piperis by Fluorometric Spectroscopy, Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting Techniques. Egyptian Journal of Botany. 2020;60(3):659-670.

Crossref - Kohler N, Sun C, Wang J, Zhang M. Methotrexate-modified superparamagnetic nanoparticles and their intracellular uptake into human cancer cells. Langmuir. 2005;21(19):8858-8864.

Crossref - Kapatia A, Gupta T, Sharma M, Khan A, Kulshrestha S. Isolation and analysis of genetic diversity amongst Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolates infecting cauliflower and pea. Indian J Biotechnol. 2016;15:589-595.

- Singh V, Khan R, Devesh P. In vitro evaluation of fungicides, bio-control agents and plant extracts against early blight of tomato caused by Alternaria solani (Ellis and Martin) Jones and Grout. International Journal of Plant Protection. 2018;11(1):102-108.

Crossref - Kriaa M, Hammami I, Sahnoun M, Azebou MC, Triki MA, Kammoun R. Biocontrol of tomato plant diseases caused by Fusarium solani using a new isolated Aspergillus tubingensis CTM 507 glucose oxidase. Comptes Rendus Biologies. 2015;338(10):666-677.

Crossref - Abdallah RAB, Jabnoun-Khiareddine H, Mejdoub-Trabelsi B, Daami-Remadi M. Soil-borne and compost-borne Aspergillus species for biologically controlling post-harvest diseases of potatoes incited by Fusarium sambucinum and Phytophthora erythroseptica. Plant Pathology & Microbiology. 2015;6:10.

Crossref - Atallah O, Yassin S. Aspergillus spp. eliminate Sclerotinia sclerotiorum by imbalancing the ambient oxalic acid concentration and parasitizing its sclerotia. Environmen Microbiol. 2020;22:5265-5279.

Crossref - Homthong M, Kubera A, Srihuttagum M, Hongtrakul V. Isolation and characterization of chitinase from soil fungi, Paecilomyces sp. Agriculture and Natural Resources. 2016;50(4):232-242.

Crossref - Krishnaveni B, Ragunathan R. Chitinase production from marine wastes by Aspergillus terreus and its application in degradation studies. International J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2014;3:76-82.

- Deng S, Lorito M, Penttila M, Harman GE. Overexpression of an endochitinase gene (ThEn-42) in Trichoderma atroviride for increased production of antifungal enzymes and enhanced antagonist action against pathogenic fungi. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2007;142:81-94.

Crossref - Birch M, Robson G, Law D, Denning DW. Evidence of multiple extracellular phospholipase activities of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infection and Immunity 1996;64(3):751-755.

Crossref - Ganendren R, Widmer F, Singhal V, Wilson C, Sorrell T, Wright L. In vitro antifungal activities of inhibitors of phospholipases from the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2004;48(5):1561-1569.

Crossref - Chandrasekaran S, Kumaresan SSP, Manavalan M. Production and optimization of protease by filamentous fungus isolated from paddy soil in Thiruvarur District Tamilnadu. Journal of Applied Biology and Biotechnology. 2015;3:66-69.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2021. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.