ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

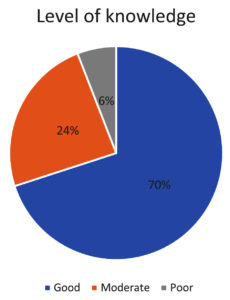

Up to April 24th 2020, the Government of Tanzania announced 284 cases of COVID-19, among them 7 were in intensive care, 37 recoveries, 10 deaths and the rest in stable condition while Dar es Salaam region was leading in number of infected cases followed by Mwanza, Arusha and Dodoma regions. This study was conducted to evaluate level of COVID-19 knowledge among healthcare workers in selected regions of Tanzania in order to identify the existing gap of knowledge in combating COVID-19. This study applied a quantitative analytical cross-sectional survey design in Dar es Salaam, Arusha, Mwanza and Dodoma regions of Tanzania from 24th of August till 3rd October, 2022. A total of 596 healthcare workers from 40 healthcare facilities were involved. Frequencies and percentages were analyzed for categorical variables. Association between categorical variables were analyzed by using Chi-square and variables were significant at P-value < 0.05. This study found that, healthcare workers have an average of 79.4% correct answers with overall level of knowledge at 70%, 24% and 6% of healthcare workers holding good, moderate and low levels of knowledge respectively. Multinomial logistic regression showed significant associations with service experience of 1-5 years (OR = 0.093, 95% CI, 0.011-0.759, P-value= 0.027) when good and poor knowledge compared. This study found moderate knowledge among healthcare workers. Significant association with level of knowledge reported in age, field profession, level of education, category of healthcare facility and situation of caring COVID-19 patients in facility.

Knowledge, Healthcare Facilities, Healthcare Workers, COVID-19, Tanzania

In December 2019, the disease caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged and was named as Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), the disease was associated with severe illness conditions and deaths.1 COVID-19 is spreading rapidly with high rate of mortality, in China the disease was classified as class B of infectious diseases but in January 2020 China was declared to manage it as a class A infectious disease.2 More than 200 countries and territories reported more than 37.1 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and more than 1.07 million deaths.3 The whole world is fighting to eradicate the disease, the country’s population has great support in the fight against the disease and public awareness is mentioned to play an essential role in combating the disease. Public awareness includes healthcare workers adequate knowledge in serving the general public, many countries such as China, South Korea, Iran and Italy have already experienced the consequences of the disease outbreak and number of deaths in a very short time as a result of lack of adequate knowledge.4 Along with the great efforts made by the government including lockdown and restriction in travelling but still the cases increased every day. The fight against COVID-19 failed due to neglecting the general public involvement in fighting the disease, healthcare workers should be well prepared to have enough knowledge to serve the general public on how to protect themselves, symptoms of the disease and available treatment updates. Governmental agencies, non-governmental organization and hospitals should help the general public as third-party supporters.4

Healthcare workers have a great role in reducing the number of morbidity and mortality in the general public by doing so they are directly interacting with patients and the causative agents. They are at a high risk of getting infections from patients if they do not have sufficient knowledge about the disease and fail to take precautions against disease. A report from China of 20th February, 2020 revealed that 2050 healthcare workers were infected with COVID-19 due to lack of awareness and experience in dealing with the disease.5 Mechanism of protecting healthcare workers and preventing nosocomial infections were among of the great challenges faced China in the battle of COVID-19.6 Avoidance of associated infection from patients to healthcare workers accompanied by provision of quality healthcare delivery system can only be achieved if all healthcare workers in general are equipped with adequate knowledge about COVID-19.7

After the first patient announced by the Ministry of Health in Tanzania from Arusha region, fear grew in the community healthcare workers who were struggling on how to protect themselves from COVID-19. On April 24th 2020, the government of Tanzania announced a total of 284 cases of COVID-19, among them 7 were in intensive care, 37 recoveries, 10 deaths and the rest were in stable condition while Dar es Salaam region was leading in number of infected cases, followed by Mwanza, Arusha and Dodoma regions.8

With a special consideration of the magnitude of the outbreak it is important to evaluate level of knowledge among healthcare personnel working with limited resources. Therefore, researching in this area in regions of Dar es Salaam, Dodoma, Mwanza and Arusha where COVID-19 transmission grew higher compared to other regions in the country, will add value to the existing level of knowledge, strengthen healthcare policy and good utilization of available but limited resources.

Study design

This study applied a quantitative analytical cross-sectional survey design in Dar es Salaam, Arusha, Mwanza and Dodoma regions of Tanzania from 24th of August till 3rd October, 2022.

Study population

Healthcare workers such as clinicians (doctors), nurses, pharmaceutical personnel, laboratory personnel and other health support staff from selected public hospitals, health centres and dispensaries were involved. Only government owned healthcare facilities were involved, private owned healthcare facilities and student healthcare workers who were in short term field practices during data collection were not involved.

Sample size

Krejcie and Morgan’s (1970) formula for calculating sample size of a known population size was used to calculate sample size.9 A total of 596 healthcare workers were involved from four regions of Tanzania, in which 172 involved from Dar es Salaam, 134 from Mwanza, 138 from Arusha and 152 from Dodoma. This study involved 40 healthcare facilities as follows; 8 hospitals, 15 health centres and 17 dispensaries.

Sampling procedure

A multi-stage sampling procedure was carried out in phases, the study areas were purposively selected due to their potential and alarm of COVID-19 prevalence.8 In healthcare facilities, purposively sampling was used to select respondent who were dedicated to care for COVID-19 patients if dedication was done in the particular healthcare facility and simple random sampling was used to select other healthcare workers in a particular healthcare facility.

Data collection

Primary data were collected from the participants by using self-administered questionnaires. Then, a pre-test of data collection tool was done to 25 healthcare workers from two healthcare facilities in Dodoma city which shared almost similar characteristics with the targeted population of this study. Completeness and accuracy of data was checked and gaps identified were modified by the researchers and tested by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Then, items testing >0.7 were regarded as reliable and those <0.7 were either modified or removed from the questionnaire.

Data Management

The quantitative primary data collected from participants were coded and analyzed by using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 26 version. Frequencies and percentages were analyzed for categorical variables. Association between categorical variables were analyzed by using Chi-square and variables were significant at P-value < 0.05. Factors influencing level of knowledge among healthcare workers were analyzed by multinomial logistic regression with predictor variables, odds ratio (OR), 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and P-values were computed, also P < 0.05 were significant.

Scoring and definitions of knowledge assessment

Bloom’s cut-off point was modified and used to classify the overall level of knowledge among healthcare workers as follows, good knowledge (≥80% to 100%), moderate knowledge (60% to <80%) and <60% classified as poor knowledge.10

Consent

Staff were given and filled informed consent form for them to participate in the study and ensure their confidentiality, staff who were not able to fill a consent form and not agreed to participate in the study were not involved.

Ethical approval

The research ethical clearance letter to conduct this study was approved and issued by the Open University of Tanzania (OUT) with reference number PG202001923 prior to the study and permission obtained from regional and district authorities of the study area.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

About 596 healthcare workers were involved in the study, whose demographic characteristics include: sex, age in years, field profession, highest level of education, if the participant was dedicated in COVID-19 team to care for infected patients in healthcare facilities and service experience in years of each participant. As elaborated in (Table 1), sex distribution involved 329 (55.2%) females who contributed higher compared to males 267 (44.8%); participants aged between 30-39 years were higher 212 (35.6%) than other age categories. In distribution of field profession nurses’ category were higher 184 (30.9%) than in the other categories. Regarding the distribution of highest level of education, the level of diploma had the largest number of 256 (43.0%) participants. Demographic characteristics of participants based on healthcare facilities, hospital category was higher 307 (51.5%) than health center 185 (31.0%) and dispensary 104 (17.4). Healthcare facilities that served outpatients and inpatients involved many participants 433 (72.7%) than outpatients only (27.3%). Based on the situation of caring patients at healthcare facilities during the first wave of COVID-19, a large number of 341 (57.2%) participants were involved from healthcare facilities that served all patients.

Table (1):

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants (N=596).

| Predictor variables | Valid response | Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 267 | 44.8 |

| Female | 329 | 55.2 | |

| Age in years | 18 – 29 | 209 | 35.1 |

| 30 – 39 | 212 | 35.6 | |

| 40 – 49 | 111 | 18.6 | |

| 50 and above | 64 | 10.7 | |

| Field profession | Clinician (doctor) | 157 | 26.3 |

| Nurse | 184 | 30.9 | |

| Pharmaceutical personnel | 90 | 15.1 | |

| Laboratory personnel | 87 | 14.6 | |

| Supportive staff | 78 | 13.1 | |

| Highest level of education | Primary school | 21 | 3.5 |

| Secondary school | 42 | 7.0 | |

| Certificate | 109 | 18.3 | |

| Diploma | 256 | 43.0 | |

| Bachelor degree | 155 | 26.0 | |

| Master degree | 13 | 2.2 | |

| Dedicated in COVID-19 team to care COVID-19 patients | Yes | 222 | 37.2 |

| No | 357 | 59.9 | |

| No dedicated team | 17 | 2.9 | |

| Service experience in years | Less than 1 | 86 | 14.4 |

| 1 – 5 | 203 | 34.1 | |

| 6 – 10 | 120 | 20.1 | |

| 11 – 15 | 73 | 12.2 | |

| 16 – 20 | 44 | 7.4 | |

| Above 20 | 70 | 11.7 | |

| Region | Dar es salaam | 172 | 28.9 |

| Mwanza | 134 | 22.5 | |

| Arusha | 138 | 23.2 | |

| Dodoma | 152 | 25.5 | |

| Category of your healthcare facility | Hospital | 307 | 51.5 |

| Health center | 185 | 31.0 | |

| Dispensary | 104 | 17.4 | |

| Type of patients served at your facility | Outpatients only | 163 | 27.3 |

| Outpatients and inpatients | 433 | 72.7 | |

| Situation of caring COVID-19 patients in healthcare facilities | Cared COVID-19 patients only | 93 | 15.6 |

| It served all patients | 341 | 57.2 | |

| It referred patients with COVID-19 symptoms | 162 | 27.2 |

Descriptive analysis of healthcare workers’ knowledge level in combating COVID-19

In this study healthcare workers had a good understanding on the question that asked about the organ which is most affected by the coronavirus and cause the use of ventilating machines where 584 (98.0%) participants gave the correct answer, followed by the question that asked the best way to protect themselves from COVID-19 where 582 (97.7%) participants gave the correct answer and the question that asked correct set of symptoms associated with COVID-19 where 579 (97.1%) participants gave the correct answer as shown in (Table 2). Similarly, there was poor awareness on the question that asked the group of higher risk patients who can develop severe illness from COVID-19 about 245 (41.1%) participants gave the correct answer, followed by the question that asked what do you know about emerging diseases where 342 (57.4%) participants gave the correct answer. Average knowledge score of healthcare workers in combating COVID-19 was 79.4%, with a mode of 80%, range 90%, maximum score being 100% and minimum score being 10% as shown in (Table 3). This study found that 70%, 24% and 6% of healthcare workers holding good, moderate and low levels of knowledge, respectively, as shown in Figure.

Table (2):

Descriptive analysis of questions pertaining to the healthcare workers’ knowledge level on COVID-19.

| Questions |

Response N =596 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Correct n (%) |

Incorrect n (%) |

|

| What do you know about emerging diseases? | 342 (57.4) | 254 (42.6) |

| Which set of factors can lead to the emergence of diseases in the community? | 533 (89.4) | 63 (10.6) |

| Which is the best way to protect yourself from COVID-19? | 582 (97.7) | 14 (2.3) |

| Which organ is most affected by the coronavirus and cause the use of ventilating machines? | 584 (98.0) | 12 (2.0) |

| Which among the following are the correct sets of coronavirus variants? | 378 (63.4) | 218 (36.6) |

| what is the appropriate time to isolate a person who is suspected of having the coronavirus? | 478 (80.2) | 118 (19.8) |

| Which is the group of higher risk patients to develop severe illness from COVID-19? | 245 (41.1) | 351 (58.9) |

| The following are correct set of symptoms associated with COVID-19 | 579 (97.1) | 17 (2.9) |

| COVID-19 reached to which stage of spread? | 426 (71.5) | 170 (28.5) |

| Which COVID-19 product is currently available in the market? | 550 (92.3) | 46 (7.7) |

Table (3):

Descriptive statistics of knowledge score of healthcare workers.

Valid (N) |

596 |

Mean |

79.4 |

Median |

80 |

Mode |

80 |

Std. Deviation |

14.5 |

Range |

90 |

Minimum |

10 |

Maximum |

100 |

Association of predictor variables and healthcare workers’ knowledge level in COVID-19

In this study, significant relationship between predictor variables and level of knowledge among healthcare workers was computed by bivariate analysis. Five predictor independent variables (age in years, field profession and level of education, category of healthcare facility and situation of caring COVID-19 patients in facility) have significant relationship with level of knowledge, all with a P-value (P< 0.05) while the other five (sex, dedication to COVID-19 team, service experience, region and patient’s category served at facility) have no significant relationship with level of knowledge, all with a P-value (P> 0.05) as shown in (Table 4).

Table (4):

Bivariate analysis of the predictor variables and level of knowledge among healthcare workers (N=596).

| Predictor variables | Valid response | Level of knowledge | Chi square | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good n (%) | Moderate n (%) | Poor n (%) | ||||

| Sex | Male | 191 (32.0) | 64 (10.7) | 12 (2.0) | 1.742 | 0.419 |

| Female | 226 (37.9) | 80 (13.4) | 23 (3.9) | |||

| Age in years | 18 – 29 | 140 (23.5) | 58 (9.7) | 11 (1.8) | 20.784 | 0.008* |

| 30 – 39 | 149 (25.0) | 48 (8.1) | 15 (2.5) | |||

| 40 – 49 | 88 (14.8) | 16 (2.7) | 7 (1.2) | |||

| 50 and above | 40 (6.7) | 22 (3.7) | 2 (0.3) | |||

| Field profession | Clinician (doctor) | 107 (18.0) | 44 (7.4) | 6 (1.0) | 19.540 | 0.012* |

| Nurse | 123 (20.6) | 48 (8.1) | 13 (2.2) | |||

| Pharmaceutical personnel | 63 (10.6) | 21 (3.5) | 6 (1.0) | |||

| Laboratory personnel | 75 (12.6) | 11 (1.8) | 1 (0.2) | |||

| Other health support staff | 49 (8.2) | 20 (3.4) | 9 (1.5) | |||

| Highest level of education | Primary school | 12 (2.0) | 7 (1.2) | 2 (0.3) | 28.077 | 0.002* |

| Secondary school | 22 (3.7) | 13 (2.2) | 7 (1.2) | |||

| Certificate | 66 (11.1) | 35 (5.9) | 8 (1.3) | |||

| Diploma | 183 (30.7) | 62 (10.4) | 11 (1.8) | |||

| Bachelor degree | 125 (21.0) | 23 (3.9) | 7 (1.2) | |||

| Master degree | 9 (1.5) | 4 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Dedicated to care COVID-19 patients | Yes | 157 (26.3) | 55 (9.2) | 10 (1.7) | 1.633 | 0.803 |

| No | 247 (41.4) | 86 (14.4) | 24 (4.0) | |||

| Dedication was not done | 13 (2.2) | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | |||

| Service experience in years | Less than 1 | 59 (9.9) | 23 (3.9) | 4 (0.7) | 6.808 | 0.743 |

| 1 – 5 | 143 (24.0) | 50 (8.4) | 10 (1.7) | |||

| 6 – 10 | 86 (14.4) | 25 (4.2) | 9 (1.5) | |||

| 11 – 15 | 52 (8.7) | 16 (2.7) | 5 (0.8) | |||

| 16 – 20 | 34 (5.7) | 7 (1.2) | 3 (0.5) | |||

| Above 20 | 43 (7.2) | 23 (3.9) | 4 (0.7) | |||

| Region | Dar es salaam | 120 (20.1) | 44 (7.4) | 8 (1.3) | 4.075 | 0.666 |

| Mwanza | 101 (16.9) | 26 (4.4) | 7 (1.2) | |||

| Arusha | 91 (15.3) | 38 (6.4) | 9 (1.5) | |||

| Dodoma | 105 (17.6) | 36 (6.0) | 11 (1.8) | |||

| Category of healthcare facility | Hospital | 229 (38.4) | 65 (10.9) | 13 (2.2) | 21.885 |

<0.001* |

| Health center | 106 (17.8) | 62 (10.4) | 17 (2.9) | |||

| Dispensary | 82 (13.8) | 17 (2.9) | 5 (0.8) | |||

| Patients served at your facility | Outpatients only | 121 (20.3) | 35 (5.9) | 7 (1.2) | 2.206 | 0.332 |

| Outpatients and inpatients | 296 (49.7) | 109 (18.3) | 28 (4.7) | |||

| The situation of caring COVID-19 patients in facility | It served only COVID-19 patients | 58 (9.7) | 31 (5.2) | 4 (0.7) | 9.537 |

0.049* |

| It served all patients | 249 (41.8) | 76 (12.8) | 16 (2.7) | |||

| It referred patients with COVID-19 symptoms | 110 (18.5) | 37 (6.2) | 15 (2.5) | |||

* P<0.05 is statistically significant

Factors influencing level of knowledge on COVID-19 among healthcare workers

The level of knowledge among healthcare workers computed by multinomial logistic regression with predictors (socio-demographic characteristics) variables. The moderate and poor categories were compared with good knowledge as the reference category.

Logistic regression results shown in (Table 5) indicates that when the moderate category was compared with good category, field profession, category of your healthcare facility and situation of caring COVID-19 patients in facility during the first wave of COVID-19 significantly predicted membership in the moderate knowledge category. Laboratory personnel in field profession exerted effect with odds decreased by a factor of 0.4 (OR = 0.359, 95% CI, 0.139-0.927), health center in category of your healthcare facility increased by a factor of 2.7 (OR = 2.677, 95% CI, 1.186-6.042) and healthcare facilities served only COVID-19 patients in situation of caring COVID-19 patients at facility during the first wave of COVID-19 increased by a factor of 2.1 (OR = 2.084, 95% CI, 1.066-4.073).

Table (5):

Multinomial logistic regression odds ratios for factors influencing level of knowledge among healthcare workers.

| Predictor variables | Good knowledge (Reference) vs Moderate knowledge | Good knowledge (Reference) vs Poor knowledge | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% C.I.for EXP(B) | P-value | AOR | 95% C.I.for EXP(B) | P-value | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.099 | 0.697 | 1.732 | 0.685 | 0.904 | 0.379 | 2.157 | 0.82 |

| Female | Reference | |||||||

| Age in years | ||||||||

| 18 – 29 | 2.287 | 0.597 | 8.762 | 0.227 | 22.896 | 1.717 | 305.396 | 0.018* |

| 30 – 39 | 1.822 | 0.529 | 6.272 | 0.341 | 14.279 | 1.329 | 153.376 | 0.028* |

| 40 – 49 | 0.761 | 0.272 | 2.129 | 0.603 | 6.673 | 0.908 | 49.019 | 0.062 |

| 50 and above | Reference | |||||||

| Field profession | ||||||||

| Clinician (doctor) | 1.295 | 0.593 | 2.828 | 0.517 | 0.348 | 0.088 | 1.377 | 0.132 |

| Nurse | 0.976 | 0.473 | 2.014 | 0.948 | 0.45 | 0.146 | 1.386 | 0.164 |

| Pharmaceutical personnel | 0.836 | 0.361 | 1.937 | 0.677 | 0.472 | 0.127 | 1.754 | 0.262 |

| Laboratory personnel | 0.359 | 0.139 | 0.927 | 0.034* | 0.066 | 0.007 | 0.622 | 0.018* |

| Other health support staff | Reference | |||||||

| Level of education | ||||||||

| Primary school | 1.46 | 0.262 | 8.135 | 0.666 | b | b | b | b |

| Secondary school | 1.317 | 0.291 | 5.954 | 0.721 | – | – | – | – |

| Certificate | 1.266 | 0.316 | 5.071 | 0.739 | – | – | – | – |

| Diploma | 0.761 | 0.2 | 2.892 | 0.688 | – | – | – | – |

| Bachelor degree | 0.364 | 0.094 | 1.413 | 0.144 | – | – | – | – |

| Master degree | Reference | |||||||

| Dedicated in COVID-19 team | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.159 | 0.268 | 5.011 | 0.843 | 0.801 | 0.075 | 8.615 | 0.855 |

| No | 1.205 | 0.277 | 5.238 | 0.803 | 1.332 | 0.126 | 14.026 | 0.812 |

| Dedication was not done | Reference | |||||||

| Service experience in years | ||||||||

| Less than 1 | 0.497 | 0.122 | 2.02 | 0.328 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 1.208 | 0.071 |

| 1 – 5 | 0.348 | 0.097 | 1.255 | 0.107 | 0.093 | 0.011 | 0.759 | 0.027* |

| 6 – 10 | 0.414 | 0.119 | 1.443 | 0.166 | 0.245 | 0.033 | 1.792 | 0.166 |

| 11 – 15 | 0.595 | 0.191 | 1.852 | 0.37 | 0.243 | 0.036 | 1.629 | 0.145 |

| 16 – 20 | 0.404 | 0.133 | 1.23 | 0.111 | 0.567 | 0.091 | 3.546 | 0.544 |

| Above 20 | Reference | |||||||

| Region | ||||||||

| Dar es salaam | 1.215 | 0.671 | 2.201 | 0.521 | 0.918 | 0.312 | 2.699 | 0.877 |

| Mwanza | 0.973 | 0.513 | 1.842 | 0.932 | 0.778 | 0.258 | 2.347 | 0.656 |

| Arusha | 1.163 | 0.636 | 2.127 | 0.623 | 0.834 | 0.29 | 2.399 | 0.736 |

| Dodoma | Reference | |||||||

| Category of your healthcare facility | ||||||||

| Hospital | 1.416 | 0.597 | 3.357 | 0.43 | 0.9 | 0.144 | 5.613 | 0.91 |

| Health center | 2.677 | 1.186 | 6.042 | 0.018* | 1.816 | 0.329 | 10.03 | 0.494 |

| Dispensary | Reference | |||||||

| Type of patients receiving healthcare at your facility | ||||||||

| Outpatients only | 0.829 | 0.423 | 1.623 | 0.584 | 0.308 | 0.07 | 1.355 | 0.119 |

| Outpatients and inpatients | Reference | |||||||

| Situation of caring COVID-19 patients at your facility during the first wave of COVID-19 | ||||||||

| It served only COVID-19 patients | 2.084 | 1.066 | 4.073 | 0.032* | 0.488 | 0.133 | 1.786 | 0.279 |

| It served all patients | 1.127 | 0.661 | 1.92 | 0.661 | 0.44 | 0.175 | 1.107 | 0.081 |

| It referred patients with COVID-19 symptoms | Reference | |||||||

* P<0.05 is statistically significant, degree of freedom (df) = 1, CI=Confidence Interval, AOR=Adjusted Odds Ratio, bN/A results were not considered due to maximum variation caused by zero odds in reference categorical variable.

Similarly, when the poor knowledge category was compared with good knowledge category, age in years, field profession and service experience in years significantly predicted membership in the poor knowledge category. Age between 18 – 29 and 30 – 39 increased by a factor of 22.9 (OR = 22.896, 95% CI, 1.717-305.396) and 14.3 (OR = 14.279, 95% CI, 1.329-153.376) respectively. Service experience of 1-5 years decreased by a factor of 0.1 (OR = 0.093, 95% CI, 0.011-0.759) and laboratory personnel in field profession exerted effect with odds decreased by a factor of 0.1 (OR = 0.066, 95% CI, 0.007-0.622).

This study found that healthcare workers have an average of 79.4% correct answers with 70%, 24% and 6% of healthcare workers holding good, moderate and low levels of knowledge, respectively. Therefore, in this study, healthcare workers are found with moderate level of knowledge which is similar to other study reported in Tanzania which found an intermediate understanding about COVID-19 among healthcare workers.11 However, the study contradicts with the study reported general good knowledge among healthcare workers in Italy, Iran and Jordan.12 This study is also contrary to the study in Turkey which revealed that about 55.11% to 64.4% of participants lack adequate knowledge concerning COVID-19.13 The discrepancies in these results may be due to the economic status of a country in question, a fact that was corroborated the study in Egypt which reiterated that healthcare providers are at the frontline to fight against COVID-19 pandemic, lack of knowledge among them can cause serious consequences to the general public and lead to failure in infection control, rapid rate of disease spread and eventually cause more deaths.14

Although in this study, healthcare workers had a good understanding on the question that asked about the organ which is most affected by the coronavirus and cause the use of ventilating machines by 98.0% followed by the question that asked the best way to protect themselves from COVID-19 by 97.7% and the question that asked correct set of symptoms associated with COVID-19 by 97.1%. The results of this study are closely related with other studies in Africa and outside Africa all of which indicated that a large number of healthcare workers who were interviewed have a good level of knowledge in relation to how COVID-19 is caused, transmitted, prevented and treated.15-19 Similarly, the study in Nigeria added that nearly all the participants were aware that the disease is transmitted from one person to another and if infected, death may be inevitable.20 Poor awareness reported in the question that asked the group of higher risk patients who can develop severe illness from COVID-19 where 41.1% participants gave the correct answer, followed by the question that asked what do you know about emerging diseases where 57.4% of participants gave the correct answer. This lack of awareness brings great fear as to whether healthcare workers can effectively fight against COVID-19 in Tanzanian healthcare facilities.

Significant association reported in field profession, in which clinicians (doctors) and nurses have significantly higher score than pharmaceutical personnel and medical laboratory personnel. This variation among field profession is similar with the study reported in Saudi Arabia after the outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-coronavirus (MERS) disease in 2016 which reported significant higher level of knowledge among nurses and doctors than pharmaceutical personnel and recommended improvement of knowledge among them.21 However, pharmaceutical personnel had good practice compared to other healthcare professions in a study conducted in Pakistan.22 These frequently reported significant differences among professions of healthcare workers may rise the alarm of unequal chance of training and overall involvement in the fight against emerging infectious diseases particularly COVID-19 which need teamwork for better achievement.

In the other side bivariate analysis showed that team dedicated to care for COVID-19 patients and service experience have no significant relationship with level of knowledge, this situation may be caused by irregular training among healthcare workers and in most cases healthcare workers may be dedicated in COVID-19 team without having special consideration in training. Another study conducted in Tanzania strengthened that, overall level of preparedness was poor at 52%, only 25% of preventive measures were good prepared and 23% moderately prepared in which regular training among healthcare workers was poorly implemented, then concluded that poor preparedness responses in Tanzania may cause less capacity to fight against COVID-19 whenever it emerges.23 Therefore, the results shows a direct relationship between poor preparedness responses and moderate knowledge reported by this current study.

Limitations of study

Unequal distribution of healthcare worker’s profession, pharmaceutical personnel were few followed by medical laboratory personnel in almost all facilities compared to clinicians (doctors) and nurses which affected equal proportion of sample size across all professions. Also, pharmaceutical personnel were not much involved in a team dedicated to care COVID-19 patients in most of healthcare facilities which limited their experiences on issues related to COVID-19.

This study found moderate level of knowledge among healthcare workers. Healthcare workers showed good awareness on the question that asked about the organ which is most affected by the coronavirus and caused the use of ventilating machines by 98.0%. Poor awareness reported in the question that asked the group of higher risk patients who can develop severe illness from COVID-19, only 41.1% participants gave the correct answer. Multinomial logistic regression showed highly significant associations with level of education when good and poor knowledge were compared.

Recommendations

- The Ministry of health in Tanzania should organize classes or plan for continuing education and strengthening regular training programme to upgrade existing knowledge bases in emerging infectious diseases.

- The relevant regulatory authorities for education such as the National Council for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (NACTVET), The Tanzania Commission for Universities (TCU) and related professional associations with collaboration of training institutions should include emerging infectious diseases modules in curricula of health-related programmes for appropriate formal knowledge to students.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all regional and district medical officers of the study areas, directors and/medical officer in charge in all healthcare facilities, heads of departments or units and healthcare workers for facilitating the success of this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the research ethical clearance, Open University of Tanzania (OUT) with reference number PG202001923.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- Paules CI, Marston HD, Fauci AS. Coronavirus infections more than just the common cold. JAMA. 2020;323(8):707-708.

Crossref - Shi B, Xia Z, Xiao S, Huang C, Zhou X, Xu H. Severe pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2 and respiratory syncytial virus infection: a case report. Clin Pediatr. 2020;59(8):823-826.

Crossref - Feng Z, Xiao C, Li P, You Z, Yin X, Zheng F. Comparison of spatio-temporal transmission characteristics of COVID-19 and its mitigation strategies in China and the US. J Geogr Sci. 2020;30(12):1963-1984.

Crossref - Gupta PK, Kumar A, Joshi S. A review of knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 with future directions and open challenges. J Public Aff. 2021;21(4):e2555.

Crossref - Malik UR, Atif N, Hashmi FK, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practices of healthcare professionals on COVID-19 and risk assessment to prevent the epidemic spread: a multicenter cross-sectional study from Punjab, Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6395.

Crossref - Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069.

Crossref - Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China. Summary of a Report of 72314 Cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242.

Crossref - Rugarabamu S, Ibrahim M, Byanaku A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) towards COVID-19: A quick online cross-sectional survey among Tanzanian residents. medRxiv. 2020.

Crossref - Krejcie RV, Morgan DW. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas. 1970;30(3):607-610.

Crossref - Feleke BT, Wale MZ, Yirsaw MT. Knowledge, attitude and preventive practice towards COVID-19 and associated factors among outpatient service visitors at Debre Markos compressive specialized hospital, north-west Ethiopia. Plos one. 2021;16(7):e0251708.

Crossref - Chilongola JO, Rwegoshola K, Balingumu O, Semvua H, Kwigizile E. COVID-19 Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Vaccination Hesitancy in Moshi, Kilimanjaro Region, Northern Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2022;23(1):1-12.

Crossref - Puspitasari IM, Yusuf L, Sinuraya RK, Abdulah R, Koyama H. Knowledge, attitude, and practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:727-733.

Crossref - Yildirim M, Guler A. COVID-19 severity, self-efficacy, knowledge, preventive behaviors, and mental health in Turkey. Death Stud. 2022;46(4):979-986.

Crossref - Wahed WYA, Hefzy EM, Ahmed MI, Hamed NS. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and perception of health care workers regarding COVID-19, a cross-sectional study from Egypt. J Community Health. 2020;45(6):1242-1251.

Crossref - Kassie BA, Adane A, Tilahun YT, Kassahun EA, Ayele AS, Belew AK. Knowledge and attitude towards COVID-19 and associated factors among health care providers in Northwest Ethiopia. PloS One. 2020;15(8):e0238415.

Crossref - Olum R, Chekwech G, Wekha G, Nassozi DR, Bongomin F. Coronavirus disease-2019: knowledge, attitude, and practices of health care workers at Makerere university teaching Hospitals, Uganda. Front Public Health. 2020;8:(181).

Crossref - Hussain I, Majeed A, Imran I, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practices toward COVID-19 in primary healthcare providers: a cross-sectional study from three tertiary care hospitals of Peshawar, Pakistan. J Community Health. 2021;46(3):441-449.

Crossref - Huynh G, Nguyen TN, Vo KN, Pham LA. Knowledge and attitude toward COVID-19 among healthcare workers at District 2 Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2020;13(6):260.

Crossref - Zhang M, Zhou M, Tang F, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Henan, China. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(2):183-187.

Crossref - Ogolodom MP, Mbaba AN, Alazigha N, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and fears of healthcare workers towards the Corona virus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in South-South, Nigeria. Health Sci J. 2020:1-10.

Crossref - Asaad AM, El-Sokkary RH, Alzamanan MA, El-Shafei M. Knowledge and attitudes towards Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (MERS-CoV) among health care workers in south-western Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;26(4):435-442.

Crossref - Saqlain M, Munir MM, Rehman SU, et al. Knowledge, attitude, practice and perceived barriers among healthcare workers regarding COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(3):419-423.

Crossref - Magwe E, Varisanga MD, Ng’weshemi SK. Healthcare facilities’ level of preparedness response on COVID-19 preventive measures in selected regions of Tanzania: A perspective of healthcare workers. Microbes Infect Dis. 2023;4(2):343-356.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2023. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.