ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

The persistence of antibiotic resistance in bacteria poses a major global health challenge, with wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) increasingly recognized as hotspots for both antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes (ARGs). This study investigated genetic mutations and phenotypic resistance profiles of bacterial isolates from three WWTPs in Windhoek, Namibia. Bacterial isolates were obtained through culture-based methods, identified using Gram staining and the Vitek system, and tested for antibiotic susceptibility via the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method in accordance with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. ARGs were detected using direct polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Key isolates included Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Citrobacter freundii, with PCR confirming the presence of the gyrA gene linked to fluoroquinolone resistance. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed resistance to ampicillin and tetracycline, and one isolate resistant to ciprofloxacin. Despite the detection of gyrA, most isolates remained susceptible to ciprofloxacin, suggesting these mutations may influence susceptibility to other fluoroquinolones rather than confer direct resistance. No amplification was observed for tetA and blaTEM genes. These findings reveal that WWTPs act as critical reservoirs and dissemination hubs for antibiotic-resistant bacteria and ARGs, emphasizing the urgent need for sustained genomic surveillance to curb their environmental and public health impact.

Antibiotic Resistance, Antibiotic Resistance Genes, Signature Mutations, Wastewater, Wastewater Treatment Plants

The discovery of antibiotics revolutionized modern medicine, providing an effective means to combat infectious diseases.1 However, the widespread and often indiscriminate use of these agents in healthcare, agriculture, and industry has accelerated the emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a global health threat that undermines the effectiveness of current treatments.2 AMR arises through a combination of genetic mutations and the acquisition of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), which collectively enable bacteria to survive antimicrobial exposure.3,4

Mutations in bacterial genes can alter antibiotic targets, inactivate drugs, or enhance efflux activity.5 For instance, gyrA mutations (Ser83Leu, Asp87Gly) confer fluoroquinolone resistance, blaTEM variants such as Asp170Asn encode extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), and rpoB mutations (S531L) are linked to rifampicin resistance.6,7 Similarly, tetA mutations enhance tetracycline efflux, while 23S rRNA alterations (A2058G) mediate macrolide resistance.8,9 Understanding these molecular signatures is essential to elucidate how resistance evolves and spreads across microbial populations.

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) have emerged as critical reservoirs and dissemination hotspots for ARGs and resistant bacteria. These systems receive inputs from domestic, hospital, and industrial sources,10,11 creating an environment rich in microbial diversity, antibiotic residues, and selective pressures that facilitate horizontal gene transfer.12 Consequently, effluents discharged from WWTPs often contain resistant bacteria and ARGs that can disseminate into natural ecosystems and potentially re-enter human populations through various exposure pathways.13,14 Studies have reported diverse and transcriptionally active ARGs in activated sludge and treated wastewater, conferring resistance to multiple antibiotic classes, including aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and β-lactams.15,16

Windhoek, Namibia, presents a unique and critical case for studying antimicrobial resistance within wastewater systems. As one of the few cities globally that extensively recycles treated wastewater for both potable and non-potable uses, understanding the microbial and genetic composition of these systems is essential for public health safety. Effluents from the three sampled wastewater treatment plants are routinely repurposed for non-potable applications such as landscape irrigation, agricultural use, and environmental augmentation. This continuous reuse cycle increases the likelihood of environmental and human exposure to antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes, warranting focused genomic and phenotypic investigation of these microbial communities.

This study investigates signature mutations and phenotypic antibiotic resistance in bacterial isolates from WWTPs in Windhoek, Namibia. By mapping resistance-associated mutations and profiling susceptibility patterns, the research provides insights into the genetic basis of resistance and the environmental persistence of ARGs. The findings reinforce the importance of continuous AMR surveillance in wastewater systems as part of a One Health strategy to mitigate the spread of resistance and safeguard public health.

Sampling sites

This study focused on three wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) situated in Windhoek, Namibia, all of which employ biological treatment processes.

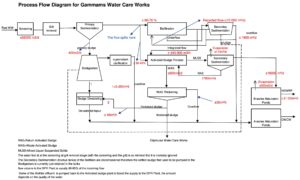

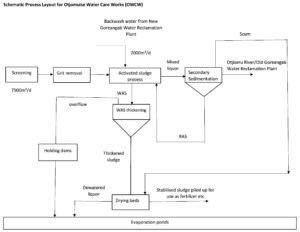

Plant A, the city’s main reclamation facility, is connected to the municipal sewer network17 and treats approximately 28,000 m³/day, serving up to 80% of Windhoek’s population through multi-stage processing that includes preliminary, primary, secondary, and advanced treatment stages (Figure 1). Plant B treats around 7500 cubic meters per day (m³/d) of mixed municipal and industrial wastewater using combined physical, chemical, and biological processes (Figure 2). Plant C serves a residential development on the outskirts of Windhoek. This plant utilizes a more advanced biological trickling filter system, incorporating primary anaerobic treatment, settling, secondary aerobic treatment, secondary clarification, and final disinfection.17,18

Figure 1. Process flow diagram of wastewater treatment plant A showing the main stages of wastewater treatment, including influent, treatment units, and effluent pathways. Arrows indicate the direction of wastewater flow

Figure 2. Process flow diagram of wastewater treatment plant B, illustrating the major treatment stages, return activated sludge (RAS), waste activated sludge (WAS), and integration of backwash water from the New Goreangab Water Reclamation Plant. Arrows indicate the direction of wastewater flow

Collection and preparation of samples

Both grab and composite samples of influent and effluent wastewater were collected usually in the mornings from each WWTP on a weekly basis over a four-week period. Sterile glass containers (Witeg, Germany, cat. No.: 5 526 500 B) were used for collection, following environmental microbiology protocols to prevent contamination, whereby the bottles were thoroughly rinsed with the sample water twice prior to sampling.19 A total 20 samples were collected and upon collection samples immediately labeled (ID, date, time, type, location) and kept cool during transport. In the lab, samples were stored at 4 °C and processed within 3 hours to preserve microbial integrity.

Bacterial isolation and identification

To ensure aseptic handling, a metal inoculating loop was sterilized by heating until red-hot over a Bunsen burner flame and cooled before use. A small aliquot of each wastewater sample was streaked onto nutrient agar plates (Millipore, SA; lot No.: HG0000C1.500) using the quadrant streaking technique to obtain isolated colonies.20 Incubation of the plates was carried out at 37 °C for a duration of 24 hours to allow the development of distinct colonies. Distinct colony morphologies were then sub-cultured to ensure purity for subsequent analysis. Pure isolates were first subjected to Gram staining to distinguish Gram-positive from Gram-negative bacteria.21 Identification was then performed using the VITEK 2 Compact system (bioMérieux, France), which determines bacterial identity based on automated biochemical profiling and database comparison. Bacterial suspensions were prepared in 0.45% saline, adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard,22 and loaded onto VITEK GN and GP identification cards (bioMérieux, SA; lots 2412771103 and 2422792403) for Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, respectively. The system provided automated identifications with corresponding confidence levels.

Identification of ARGs using PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from pure bacterial cultures using the ZymoBIOMICS Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, USA; catalog number D6005), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.23 The purity and concentration of extracted DNA were evaluated using a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) and genomic gel electrophoresis. PCR amplification was conducted in a 25 µL reaction volume comprising 12.5 µL of 2 × PCR Master Mix, 1 µL each of forward and reverse primers (10 µM), 2 µL of template DNA, and 8.5/ µL of nuclease-free water.24 Primers targeting the blaTEM, gyrA and tetA genes were synthesized by Inqaba Biotechnical Industries (Pty) Ltd (South Africa). The thermal cycling protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 32 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 seconds, annealing at 56 °C for 35 seconds, and extension at 72 °C for 35 seconds, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 8 minutes24 (Table 1). A no-template negative control was included. PCR products (3 µL) were then run on a 1.5% agarose gel (with ethidium bromide) at 100 V for 45 min alongside a 1 kb ladder for size reference. The bands of DNA products were viewed under the Gel Documentation System.

Table (1):

Targeted antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), primer sequences, amplicon sizes, and melting temperatures used for PCR amplification

Gene |

Forward Primer Sequence |

Reverse Primer Sequence |

Amplicon Size (bp) |

Melting temp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

blaTEM |

5’-ATAAAATTCTTGAAGAC-3’ |

5’-TTACCAATGCTTAATCA-3’ |

~858 bp |

32 °C |

tetA |

5’-GTAATTCTGAGCACTGTCGC-3’ |

5’-CTGCCTGGACAACATTGCTT-3’ |

~210 bp |

45 °C |

gyrA |

5’-CGACCTTGCGAGAGAAAT-3’ |

5’-GTTCCATCAGCCCTTCAA-3’ |

~620 bp |

48 °C |

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

Antibiotic susceptibility of the bacterial isolates was assessed using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion technique. The procedure followed the interpretive standards of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2018).18 Pure bacterial colonies were suspended in sterile saline to achieve a concentration equivalent to the 0.5 McFarland standard (approximately 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL), and the suspension was then evenly spread onto Mueller-Hinton agar (Millipore, SA; lot No.: HG000C37.500) using a sterile swab. Antibiotic disks saturated with antimicrobial agents [Tetracyclines (30 µg), Ciprofloxacin (5 µg) and Ampicillin (10 µg)] were then placed on a lawn of known bacteria seeded on the surface of the inoculated media. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C. Following incubation, the diameters of the inhibition zones were measured and categorized as susceptible (S), intermediate (I), or resistant (R) according to the zone diameter breakpoints specified by the CLSI standards for the various bacterial groups tested. It is noteworthy that although CLSI guidelines are developed for clinical isolates, they may be applied to environmental and wastewater bacteria, particularly clinically relevant species like Enterobacterales (which were predominant in this study), to enable standardized interpretation of resistance profiles. It is acknowledged, however, that these breakpoints may not fully reflect the behavior of environmental isolates.

Antibiotic susceptibility results were interpreted using CLSI breakpoints (Table 2) and subsequently analyzed statistically to compare resistance patterns across different wastewater treatment plants.

Table (2):

The standard AST breakpoints as per Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

| Antibiotic | Abbreviation | Antibiotic sensitivity rating | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible (S) | Intermediate (I) | Resistant (R) | ||

| Ampicillin | AMP | ≥8 | 18-20 | ≤16 |

| Ciprofloxacin | CIP | ≥15 | 10-14 | ≤4 |

| Tetracyclines | TET | ≥19 | 15-18 | ≤14 |

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed using descriptive, comparative, and inferential statistical methods. Descriptive statistics such as averages, standard deviations, and frequency counts were applied to summarize the distribution of bacterial species, patterns of antibiotic resistance, and gene presence. Comparative analysis was performed using chi-square tests to assess associations between bacterial species, resistance phenotypes, and wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) sources. Inferential statistical methods were used to assess if the differences in resistance patterns were statistically meaningful, with significance set at a p-value below 0.05. Graphical representations of the data were created using GraphPad Prism version 6 and Microsoft Excel.

Bacterial identification

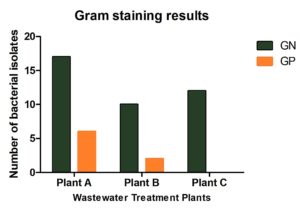

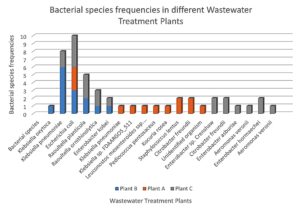

A total of 47 bacterial isolates were recovered from wastewater samples collected from the three treatment plants: Plant A (23 isolates), Plant B (12 isolates), and Plant C (12 isolates). Among these, 83% were Gram-negative and 17% were Gram-positive (Figure 3). The most frequently identified species were Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Citrobacter freundii, with E. coli occurring at all sites (Figure 4). Plant B was dominated by K. pneumoniae and E. coli, while Plant A exhibited greater species diversity, including K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and Raoultella planticola. Plant C contained a high proportion of E. coli, Raoultella planticola, and Enterobacter spp. Based on VITEK system analysis, Kocuria rosea, Staphylococcus lentus, and Pediococcus pentosaceus were identified with high confidence, indicating a diverse microbial community.

Figure 3. Distribution of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial isolates across Plants A, B, and C (n = 47). Gram-positive bacteria predominated in Plants B and C, whereas Plant A showed a balanced composition

Figure 4. Distribution of bacterial species across the three wastewater treatment plants. Significant variation was observed among sites (c² = 45.87, df = 4, p < 0.0001), with Escherichia coli being most prevalent and Plant A showing the highest diversity

The bacterial species isolated from wastewater treatment plants (E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Citrobacter freundii, among others) are known to harbor antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), and their presence in wastewater highlights the environment as significant reservoirs for resistance.25 Studies have documented that Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae frequently harbor beta-lactamase genes (e.g., blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M), which confer resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics.26,27 The identification of these genes in wastewater isolates indicates significant risk for the spread of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains into the environment.28 The dominance of Gram-negative isolates is consistent with previous studies reporting their prevalence in environments impacted by human and animal waste.29,30 Their outer-membrane structures and lipid A modifications promote multidrug-resistance by reducing permeability and supporting ARG exchange.2 Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are essential components of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, contributing to membrane stability and protection against environmental stress. These organisms often harbor antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) that provide multidrug resistance to clinically significant antibiotics and facilitate the spread of resistance across environmental and clinical settings.31

Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca were identified in several wastewater samples making them important indicators of β-lactamase activity.32 Similarly, Enterobacter spp. and Citrobacter freundii are known to harbor extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) suggesting potential dissemination of extensively drug-resistant phenotypes. E. coli often carries gyrA mutations related to fluoroquinolone resistance and blaTEM genes, emphasizing its role in ARG transmission.33 The detection of opportunistic species such as Raoultella spp. and Aeromonas spp., further highlights wastewater as a conduit for clinically relevant resistance determinants.

Among Gram-positive isolates, K. rosea appeared in roughly 98% of the collected samples. Though typically benign, it can resist β-lactams and tetracyclines through bla (beta-lactamase) and tet resistance genes.34,35 The significant abundance of this bacterium in wastewater indicates its potential to carry resistance genes that could be passed on to other harmful bacteria through horizontal gene transfer within this setting. S. lentus, a coagulase-negative staphylococcus, has also been previously reported to have potential for multidrug-resistance via bla, tetK, and tetM.36 Leuconostoc mesenteroides ssp. cremoris was also identified in over 90% of samples, indicating that even lactic-acid bacteria can serve as ARG reservoirs in wastewater systems.

Species distribution varied by site (Figure 4) and likely reflected socioeconomic and infrastructural differences. Plant C, which treats wastewater from higher-income households, showed greater bacterial diversity, likely due to higher levels of nutrients and pharmaceuticals in the influent. This pattern aligns with evidence from previous studies that have linked economic indicators such as income levels, export activity, and education related to antibiotic use, hygiene, and healthcare practices, suggesting that socioeconomic status (SES) can shape bacterial profiles in urban wastewater systems.37 In contrast, Plant B’s simpler wastewater profile yielded lower diversity, dominated by fecal-associated species such as K. pneumoniae and R. planticola. The lower bacterial diversity observed in Plant B reflects its socioeconomic status, where wastewater inputs are likely to be simple, with fewer pharmaceutical or industrial contributions. Species like Klebsiella pneumoniae and Raoultella planticola may dominate due to a focus on basic sanitation and untreated wastewater containing fecal contamination and simple organic matter. Plant A, which receives mixed domestic and industrial effluents, exhibited the broadest species range, including R. planticola, E. cloacae, and K. pneumoniae. This diversity likely reflects the heterogeneous nature of the influent, as mixed industrial and domestic discharges introduce a wide range of nutrients and chemical compounds that create varied ecological conditions supporting both environmental and fecal-associated bacteria.31,37,38

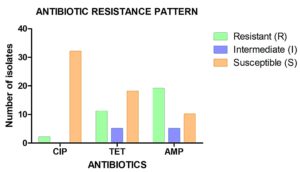

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) revealed distinct resistance trends among the three wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), reflecting differences in influent composition, treatment efficiency, and the socioeconomic characteristics of the serviced populations (Figure 5). Overall, the highest resistance was observed in Plant A, followed by Plant B, while Plant C exhibited the lowest resistance rates. These findings suggest that both anthropogenic activities and local living conditions may shape resistance dissemination within wastewater systems.39

Figure 5. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of bacterial isolates across tested antibiotics. High sensitivity was observed to ciprofloxacin, with notable resistance to ampicillin and variable responses to tetracycline

Ampicillin resistance was the most prevalent, detected in more than 90% of isolates, particularly among Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. This widespread β-lactam resistance is consistent with the dominance of β-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales in wastewater environments receiving mixed or industrial discharges. This indicates that these isolates may have exhibit β-lactamase production or other resistance mechanisms, such as enzymatic destruction by β-lactamases, target alteration of the PBPs that prevents β-lactam binding, and control of β-lactam entry and efflux.4 In contrast, tetracycline resistance was moderate and variable across sites, whereas most isolates remained susceptible to ciprofloxacin despite the detection of the gyrA gene associated with fluoroquinolone resistance. Comparable studies have similarly reported extensive resistance to older antibiotic classes such as β-lactams and tetracyclines, while fluoroquinolone resistance remains comparatively lower.22,28,40

Ciprofloxacin is a fluoroquinolone that works against a variety of Gram-negative and some Gram-positive bacteria by targeting DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. Often, gyrA and parC gene variants mediate resistance to ciprofloxacin.37 Many of the bacterial isolates were susceptible (S) to ciprofloxacin, suggesting the presence of an efflux pump mechanism or potential gyrA gene alterations. Tetracycline resistance is commonly mediated by tetA, tetB, or tetM genes, which encode efflux pumps or ribosomal protection proteins. A previous study found that Tetracycline resistance to Enterococcus spp. is widespread and may be rising. Tetracycline resistance among Klebsiella, Providencia, Raoultella, and Citrobacter spp. likely reflects the presence of plasmid-borne tet genes, which facilitate horizontal gene transfer in wastewater environments.28

Plant A demonstrated the broadest range of resistant species and the greatest multidrug- resistance potential. This plant receives both domestic and industrial effluents, including hospital inputs, generating a complex mixture of antibiotics, heavy metals, and organic compounds that enhance selective pressure for antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs). The high ampicillin and tetracycline resistance observed in Plant A likely reflects co-selection within such mixed inputs. Similar observations have been reported in mixed-use WWTPs where industrial and hospital waste streams significantly elevate resistance gene diversity.41

In Plant B, resistance was mainly associated with K. pneumoniae and Raoultella planticola, showing high ampicillin resistance but moderate tetracycline susceptibility. The limited resistance range and lower diversity likely reflect simpler domestic wastewater inputs with minimal industrial or pharmaceutical contributions. Such conditions, typical of lower-income areas, promote fecal contamination-driven resistance but offer fewer chemical pressures for complex ARG selection.33 In contrast, Plant C, serving higher-income residential households, exhibited the lowest resistance levels, with most isolates susceptible to all antibiotics. This trend likely results from reduced empirical antibiotic use, better healthcare oversight, and improved sanitation infrastructure.37 The low detection of gyrA further supports the role of socioeconomic and infrastructural factors in shaping resistance in community wastewater.41,42

Influent and effluent samples across all sites showed that resistance was consistently higher in influent samples, particularly for ampicillin, indicating that treatment processes substantially reduce but do not eliminate resistant bacteria. The persistence of resistant isolates and detection of gyrA in effluents emphasize the limited efficacy of conventional biological treatments in removing resistant determinants. Previous studies likewise found that secondary and tertiary treatment stages decrease bacterial loads but allow ARGs to survive and disseminate into receiving waters.10,43

The persistence of resistant bacteria and ARGs in treated effluents poses clear environmental and public-health risks, especially given that reclaimed water in Windhoek is reused for irrigation and other non-potable applications. Such reuse could facilitate horizontal gene transfer of resistance determinants to soil and aquatic microbiomes, potentially affecting human and animal health through environmental exposure. Similar findings have been documented elsewhere, where β-lactamase-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae released via effluents contribute to downstream accumulation of ARGs in aquatic ecosystems.27,31

Although most isolates remained susceptible to ciprofloxacin, the detection of the gyrA gene suggests the potential for resistance to other fluoroquinolone antibiotics. This trend is consistent with previous research showing widespread resistance to older antibiotics such as tetracyclines and β-lactams, while fluoroquinolone resistance appears to be emerging.13,28 There was a varying inhibitory effect exhibited by tetracycline across the tested samples. While many samples were sensitive, a significant number also show resistance, with zones of inhibition as low as 0 mm in several cases. Intermediate results (zones around 12-16 mm) indicate that tetracycline resistance is evolving and may vary depending on environmental factors or bacterial species.

Among Gram-positive bacteria, particularly Kocuria rosea, Staphylococcus lentus, and Leuconostoc spp., are known to harbor various ARGs, including bla, Tet, and gyrA genes, which may provide resistance to β-lactams, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones, respectively.44 The broad resistance to ampicillin and tetracycline supports the likelihood that these species may carry such ARGs, with β-lactamase activity explaining the high ampicillin resistance observed. Further molecular characterization is required to identify specific mutations enhancing these resistance traits, particularly in S. lentus and K. rosea, Staphylococcus lentus and Kocuria rosea.

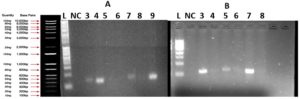

Detection of ARGs by PCR

PCR analysis detected the presence of the gyrA gene, linked to fluoroquinolone resistance, in selected isolates, as shown in Figure 6. No amplification was observed for tetA or blaTEM genes, suggesting their absence or low prevalence in the sampled bacterial population.

Figure 6. Agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5%) of amplified gyrA gene products from bacterial isolates recovered from wastewater

(A) Lane 1: 1 Kb DNA ladder; NC: negative control; Lanes 3-9: bacterial samples. Positive amplification observed in lanes 3 (140 GE2), 4 (161 EI2), 7 (139 GE1), and 9 (159 OE4), confirming the presence of the gyrA gene. No amplification detected in lanes 5 (135 OE4), 6 (133 OE2), and 8 (141 GE3).

(B) Lane 1: 1 Kb DNA ladder; NC: negative control; Lanes 3-8: bacterial samples. No amplification detected in any sample, indicating the absence of the gyrA gene

The detection of the gyrA gene, a key marker of fluoroquinolone resistance, in several isolates indicates the potential for resistance development and dissemination within wastewater environments. In contrast, the absence of tetA and blaTEM amplification may reflect either the low occurrence of these genes in the sampled bacterial population or limitations in PCR sensitivity under the applied conditions. The amplification of gyrA is particularly significant, as it suggests that these bacteria may already possess or have the potential to develop fluoroquinolone resistance through mutations within the quinolone resistance determining region (QRDR).45 The amplification of this gene across multiple bacterial isolates suggests the potential presence of signature mutations (e.g., at codons 83 or 87), which are known to confer resistance.45

Considering that most isolates carrying gyrA were found in effluent samples, highlights environmental and public health risks. Wastewater effluent can spread antibiotic-resistant bacteria and genes like gyrA into natural water bodies. A similar investigation done on E. coli shows high fluoroquinolone resistance via gyrA and parC mutations across various environments affected by wastewater discharge.46 These findings indicate that discharges from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) could contribute to the growth and spread of antibiotic resistance in streambed biofilms. Moreover, the study revealed that antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) were detectable in biofilms at considerable distances downstream from the WWTP discharge point, extending up to 1 km.46 The presence of the gyrA gene, linked to fluoroquinolone resistance, indicates that bacteria harboring it can persist and thrive in environments exposed to these widely used clinical and agricultural antibiotics.47 After entering the environment, these resistant bacteria may engage with native microbial populations, potentially passing resistance genes to other bacteria via horizontal gene transfer. This transmission can lead to the formation of environmental reservoirs of antibiotic resistance, especially in aquatic ecosystems, where resistance genes may travel through the food web and eventually impact both humans and animals. For instance, people and animals exposed to contaminated water through drinking, recreational activities, or agriculture could acquire resistant infections that are more challenging to treat.48

Similar findings in other regions have shown WWTP effluents as significant sources of resistant bacteria into natural ecosystems, raising public health concerns.49 In studies where tetA and blaTEM genes were detected, conditions such as higher anthropogenic influence or direct hospital wastewater discharges have often contributed to increased ARG prevalence. In contrast, the lower prevalence of these genes in this study suggests that either the environmental or treatment plant factors in Windhoek may limit their spread.

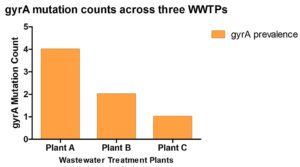

The low prevalence of gyrA in Plant C as shown in Figure 7 is consistent with its high living standard and relatively clean wastewater inputs. Affluent households may use fewer broad-spectrum antibiotics like fluoroquinolones due to better access to targeted healthcare interventions or awareness about antibiotic stewardship. Effective sanitation infrastructure may also reduce the retention and the spread of microorganisms resistant to antibiotics.43 The moderate gyrA prevalence in Plant B may reflect lower living standards, where antibiotic misuse and limited sanitation promote resistant bacteria. In contrast, the highest gyrA prevalence in Plant A is expected, as it treats wastewater from diverse sources which includes residential, industrial, and hospital effluents. The mixing of these wastes, along with potential accumulation of resistance genes and recirculation of treated effluent, likely enhances the persistence of gyrA at this site. Exploring various types of wastewater and conducting a wider analysis of antibiotic resistance genes could offer deeper understanding of how these genes spread in the environment.50

Figure 7. Prevalence of gyrA mutations among bacterial isolates from three wastewater treatment plants (Plants A, B, and C). Plant A exhibited the highest mutation prevalence, followed by Plant B and Plant C

Implications for wastewater treatment and public health

These findings highlight that wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) could serve as key locations where antibiotic resistance develops and spreads. Despite effectively lowering the number of bacteria, current treatment methods may not fully remove antibiotic resistance genes, such as the gyrA gene. As a result, these genes along with ampicillin resistant isolates, may still be released into their effluent receiving environments such as natural water bodies.43 This points to the need for continuous AMR surveillance and advanced treatment strategies that target both bacterial pathogens and ARGs to mitigate resistance spread. Effective strategies might include incorporating AMR monitoring in the current wastewater quality and risk assessments, optimization of treatment processes, and integration of newer disinfection technologies like UV-C irradiation or ozonation in some of the sampled WWTPs. As these may be more effective at degrading genetic material associated with resistance.

Bacterial isolates obtained from wastewater were analyzed using culture-based antibiotic susceptibility testing and PCR to explore both phenotypic and genetic resistance features. The isolates displayed varied phenotypic resistance patterns, and the gyrA gene which is linked to fluoroquinolone resistance was detected in several samples. Despite this, only one isolate showed phenotypic resistance to ciprofloxacin, suggesting that specific gyrA mutations may modulate resistance expression rather than directly confer it. The absence of blaTEM and tetA amplification indicates that these organisms may employ other genetic mechanisms to tolerate β-lactam and tetracycline exposure. Overall, the findings show that even non-pathogenic bacteria in wastewater can act as reservoirs for antimicrobial resistance, contributing to its persistence and posing a potential threat to public health. Continuous surveillance using genomic and metagenomic tools is recommended to uncover additional resistance determinants and inform strategies to curb environmental dissemination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST) for providing the facilities and resources necessary for this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

LMM conceived and designed the experiments. LMM contributed in reagents/materials/analysis tools. JNE and GKK performed the experiments. JNE, GKK, OEB and LMM analyzed the data. JNE, GKK and LMM wrote the manuscript. GKK, LNN, FSS, OEB and LMM reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Bobate S, Mahalle S, Dafale NA, Bajaj A. Emergence of environmental antibiotic resistance: Mechanism, monitoring and management. Environ Adv. 2023;13:100409.

Crossref - Gauba A, Rahman KM. Evaluation of Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;12(11):1590.

Crossref - Mancuso G, Midiri A, Gerace E, Biondo C. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens. 2021;10(10):1310.

Crossref - Muteeb G, Rehman MT, Shahwan M, Aatif M. Origin of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance, and Their Impacts on Drug Development: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(11):1615.

Crossref - Jacoby GA, Low KB. Genetics of Antimicrobial Resistance. US: National Academies Press 1980. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK216503/

- Hooper DC, Jacoby GA. Topoisomerase Inhibitors: Fluoroquinolone Mechanisms of Action and Resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6(9):a025320.

Crossref - Negrei C, Bo D. The Mechanisms of Action and Resistance to Fluoroquinolone in Helicobacter pylori Infection. Roesler, B. (Ed.). Trends in Helicobacter pylori Infection. InTech. 2014.

Crossref - Marti H, Bommana S, Read TD, et al. Generation of Tetracycline and Rifamycin Resistant Chlamydia Suis Recombinants. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:630293.

Crossref - Li B-B, Wu C-M, Wang Y, Shen J-Z. Single and dual mutations at positions 2058, 2503 and 2504 of 23S rRNA and their relationship to resistance to antibiotics that target the large ribosomal subunit. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(9):1983-1986.

Crossref - Drane K, Sheehan M, Whelan A, Ariel E, Kinobe R. The Role of Wastewater Treatment Plants in Dissemination of Antibiotic Resistance: Source, Measurement, Removal and Risk Assessment. Antibiotics. 2024;13(7):668.

Crossref - Zongbao L, Khumper U, Liu Y, et al. Metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses reveal activity and hosts of antibiotic resistance genes in activated sludge. Environ Int. 2019;129:208-220.

Crossref - Diaz-Palafox G, de Jesus Tamayo-Ordonez Y, Bello-Lopez JM, et al. Regulation Transcriptional of Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) in Bacteria Isolated from WWTP. Curr Microbiol. 2023;6;80(10):338.

Crossref - Pazda M, Rybicka R, Stolte S, et al. Identification of Selected Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Two Different Wastewater Treatment Plant Systems in Poland: A Preliminary Study. 2020;25(12):2851.

Crossref - Zhang H, He H, Chen S, et al. Abundance of antibiotic resistance genes and their association with bacterial communities in activated sludge of wastewater treatment plants: Geographical distribution and network analysis. J Environ Sci (China). 2019;82:24-38.

Crossref - Nyashanu PN, Shafodino FS, Mwapagha LM. Determining the potential human health risks posed by heavy metals present in municipal sewage sludge from a wastewater treatment plant. Scientific African. 2023;20:e01735.

Crossref - Malcom HB, Bowes DA. Use of Wastewater to Monitor Antimicrobial Resistance Trends in Communities and Implications for Wastewater-Based Epidemiology: A Review of the Recent Literature. Microorganisms 2025;13(9):2073.

Crossref - Water treatment plant launched. Namibia Economist. 2015. https://economist.com.na/1052/general-news/water-treatment-plant-launched/

- Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (CLSI). 2020;30th ed. https://clsi.org/shop/standards/m100/

- Wastewater sampling: SESD operating procedure SESDPROC-306-R3. 2013. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-06/documents/Wastewater-Sampling.pdf

- Sanders ER. Aseptic Laboratory Techniques: Plating Methods. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2012;63:3064.

Crossref - Tripathi N, Zubair M, Sapra A. Gram Staining. StatPearls. 2007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562156/

- Ling TKW, Tam PC, Liu ZK, Cheng AFB. Evaluation of VITEK 2 Rapid Identification and Susceptibility Testing System against Gram-Negative Clinical Isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(8):2964-2966.

Crossref - Shen Z. DNA extraction with Zymo Quick-DNA™ fungal/bacterial miniprep kit. protocols.io. Published 2025.

Crossref - Lorenz LC. Polymerase Chain Reaction: Basic Protocol Plus Troubleshooting and Optimization Strategies. J Vis Exp. 2012;22(63):3998.

Crossref - Zhang CM, Xu LM, Wang XC, Zhuang K, Liu QQ. Effects of ultraviolet disinfection on antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli from wastewater: inactivation, antibiotic resistance profiles and antibiotic resistance genes. J Appl Microbiol. 2017;123(1):295-306.

Crossref - Li S, Ondon BS, Ho S-H, Jiang J, Li F. Antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes in wastewater treatment plants: From occurrence to treatment strategies. Sci Total Environ. 2022;838(part 4):156544.

Crossref - Filonenko H, Ishchenko V, Garcia D, Tsedyk V, Korniyenko V, Ishchenko L. The frequency of β-lactamase genes in ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Ukraine. 2024;15(3):436-40.

Crossref - Godinho O, Lage OM, Quinteira S. Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria across a Wastewater Treatment Plant. Appl Microbiol. 2024;4(1):364-375.

Crossref - Avatsingh AU, Sharma S, Kour S, et al. Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria having extended-spectrum β-lactamase phenotypes in polluted irrigation-purpose wastewaters from Indian agro-ecosystems. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1227132.

Crossref - Sekyere JO, Reta MA. Genomic and Resistance Epidemiology of Gram-Negative Bacteria in Africa: a Systematic Review and Phylogenomic Analyses from a One Health Perspective. mSystems. 2020;5(6):e00897-20.

Crossref - Nobre JG, Costa DA. “Sociobiome”: How do socioeconomic factors influence gut microbiota and enhance pathology susceptibility? – A mini-review. Front Gastroenterol 2022;1.

Crossref - Rui Y, Qiu G. Analysis of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Water Reservoirs and Related Wastewater from Animal Farms in Central China. Microorganisms. 2024;12(2):396.

Crossref - Ejaz H, Younas S, Abosalif KOA, et al. Molecular analysis of blaSHV, blaTEM, and blaCTX-M in extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae recovered from fecal specimens of animals. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0245126.

Crossref - Ziogou A, Giannakodimos I, Giannakodimos A, Baliou S, Ioannou P. Kocuria Species Infections in Humans-A Narrative review. Microorganisms. 2023;11(9):2362.

Crossref - Etedali N, Doudi M, Torabi LR, Pazandeh MH. Resistance to antibiotics and ability to tolerate heavy metals in bacteria isolated from Razi industrial wastewater treatment plant and effluent of refinery units in Isfahan, Iran. 2023; Journal of Applied Research in Water and Wastewater, 10(1), 91-98.

Crossref - Rivera M, Dominguez MD, Mendiola NR, Roso GR, Quereda C. Staphylococcus lentus Peritonitis: A Case Report. Perit Dial Int. 2014;34(4):469-470.

Crossref - Ren M, Du S, Wang J. Socioeconomic drivers of the human microbiome footprint in global sewage. Front Environ Sci. 2024;18(10):129.

Crossref - Islam MMM, Shafi S, Bandh SA, Shameem N. Impact of environmental changes and human activities on bacterial diversity of lakes. Freshwater Microbiology. 2019:105-36.

Crossref - Czatzkowska M, Wolak I, Harnisz M, Korzeniewska E. Impact of Anthropogenic Activities on the Dissemination of ARGs in the Environment-A Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12853.

Crossref - Samreen, Hesham I, Malak HA, Abulreesh HH. Environmental antimicrobial resistance and its drivers: a potential threat to public health. 2021;27:101-11.

Crossref - Wang J, Mao D, Mu Q, Luo Y. Fate and proliferation of typical antibiotic resistance genes in five full-scale pharmaceutical wastewater treatment plants. 2015;526:366-373.

Crossref - Haenni M, Dagot C, Chesneau O, et al. Environmental contamination in a high-income country (France) by antibiotics, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and antibiotic resistance genes: Status and possible causes. Environ Int. 2022;159:107047.

Crossref - Turolla A, Cattaneo M, Marazzi F, Mezzanotte V, Antonelli M. Antibiotic resistant bacteria in urban sewage: Role of full-scale wastewater treatment plants on environmental spreading. Chemosphere. 2018;191:761-769.

Crossref - Lindgren PK, Karlsson A, Hughes D. Mutation rate and evolution of fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(10):3222-3232.

Crossref - Pazhani GP, Chakraborty S, Fujihara K, Yamasaki S, Ghosh A, Nair GB, Ramamurthy T. QRDR mutations, efflux system & antimicrobial resistance genes in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from an outbreak of diarrhoea in Ahmedabad, India. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134(2):214-23.

- Mutuku CS, Gazdag Z, Melegh S. Occurrence of antibiotics and bacterial resistance genes in wastewater: resistance mechanisms and antimicrobial resistance control approaches. In: Khan A, Al-Harrasi A (eds). Prime Archives in Immunology: 2nd Edition. Vide Leaf. 2022.

Crossref - Mutuku C, Melegh S, Kovacs K, et al. Characterization of β-Lactamases and Multidrug Resistance Mechanisms in Enterobacterales from Hospital Effluents and Wastewater Treatment Plant. Antibiotics. 2022;11(6): 776.

Crossref - Barathe P, Kaur K, Reddy S, Shriram V, Kumar V. Antibiotic pollution and associated antimicrobial resistance in the environment. J Hazard Mater Lett. 2024;5:100105.

Crossref - Fouz N, Pangest KNA, Yasir M, et al. The Contribution of Wastewater to the Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistance in the Environment: Implications of Mass Gathering Settings. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2020;5(1):33.

Crossref - Mukherjee M, Laird E, Gentry TJ, Brooks JP, Karthikeyan R. Increased Antimicrobial and Multidrug Resistance Downstream of Wastewater Treatment Plants in an Urban Watershed. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:657353.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.