ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Surgical site infections (SSIs) are a frequent cause of postoperative morbidity and mortality, leading to prolonged hospital stays, increased healthcare costs, and additional antibiotic use. The rising occurrence of infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms further complicates management. Continuous hospital-acquired infection (HAI) surveillance, adherence to infection prevention protocols, and timely surgical prophylaxis play a critical role in SSI prevention. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of SSIs in a tertiary care teaching hospital, identify the bacterial pathogens, evaluate their antimicrobial resistance patterns, and emphasize the need for targeted preventive strategies. A retrospective analysis was conducted in the Department of Microbiology, NRI General Hospital, Andhra Pradesh, India, over a two-year period (August 2023-July 2025). Postoperative patients with suspected SSIs were evaluated, and specimens were collected under aseptic precautions. Microbiological identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were performed using standard protocols and the VITEK 2 Compact system, following CLSI guidelines. Isolates were screened for methicillin resistance, extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production, carbapenem resistance, and multidrug-resistance. Out of 21,952 surgeries, 50 culture-positive SSI cases were identified (0.23%). The majority occurred in the 21-40 year age group (56%) and in females (68%). Obstetrics and Gynecology accounted for most infections (58%), predominantly after emergency surgeries. The leading organism was Escherichia coli (40%), followed by Klebsiella spp. (26%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12%). Resistance patterns revealed MRSA (4%), MDR (8%), ESBL producers (14%), and carbapenem resistance (14%). E. coli showed high susceptibility to tigecycline (90%) and amikacin (80%), while Klebsiella spp. and Pseudomonas spp. isolates responded best to tigecycline and carbapenems, respectively. Although SSI prevalence was low, infections were concentrated in emergency obstetric procedures and mainly caused by Gram-negative bacilli. The detection of ESBL and carbapenem-resistant strains emphasizes the need for robust infection control, antimicrobial stewardship and timely prophylactic measures to reduce SSI risk and improve outcomes.

Surgical Site Infection (SSI), Antimicrobial Stewardship, Infection Control, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hospital Acquired Infection (HAI)

Surgical site infections (SSIs) are a major cause of morbidity in hospitalized patients and constitute a serious global public health concern.1 infections at or near the surgical incision site that occurs within 30 days of surgery depending on the type of procedure are known as surgical site infections (SSIs).2 These infections may be limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissues, or they may occur deeper, involving organs or body cavities.3 SSIs often result in increased length of hospitalization, thereby significantly increasing the burden of healthcare costs.4

SSIs continue to serve as a prominent reason for rising morbidity and mortality with increasing strain on healthcare costs.4,5 Risk factors for SSIs include the level of contamination at the surgical site and virulence of the invading microorganisms interacting with patient’s immune response.6 Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., and Pseudomonas spp. are often attributed to Surgical site infections.7,8

The operating room environment, surgical tools used, and the patient’s endogenous flora can harbor exogenous and endogenous microbes responsible for SSIs. Strict adherence to infection prevention and control guidelines is thus essential for lowering the incidence of SSIs.9 Recently, the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains among hospital-acquired pathogens has become an alarming global threat for clinicians.10,11 Broad-spectrum antibiotics are extensively used for the prevention of SSI, and their prompt initiation is essential to reduce treatment costs and minimize morbidity and mortality rates related to these infections.12

Consequently, infections caused by MDR strains are associated with longer stays in hospitals, increased rates of readmission, additional use of antimicrobial agents, and a greater chance of treatment failure.13 The rapid emergence of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) is particularly concerning, as Hospital-acquired infections caused by multidrug-resistant GNB have been linked to significantly increased mortality rates compared to infections caused by non-MDR strains.14

Objective in this current study is to assess the prevalence of surgical site infections in a tertiary care hospital, assess the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of the isolated pathogens, and emphasize the role of hospital-acquired infection (HAI) surveillance in reducing SSIs. In addition, the study highlights the importance of prompt administration of prophylactic antibiotics before surgery as a crucial strategy to reduce the incidence of postoperative infections, both in elective and emergency surgeries.

This retrospective study was carried out in the Department of Microbiology, NRI General Hospital, Chinakakani, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh, India, over a two-year period from August 2023 to July 2025. The study population included postoperative patients who developed clinical features suggestive of surgical site infection (SSI) during their hospital stay or follow-up.

Out of a total of 21,952 surgeries performed during the study period, specimens were collected only from patients showing signs and symptoms at the surgical site such as wound gaping, discharge of serous fluid or pus, local erythema, tenderness, swelling, or systemic symptoms like fever and malaise. Patients with non-surgical wound infections were excluded, as the focus of this study was to determine the SSI rate and analyze the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of the associated pathogens.

A total of 50 culture-positive SSI isolates were obtained over the study period. Clinical specimens, including wound swabs, pus samples, discharges, and aspirates, were collected under aseptic precautions and processed following standard microbiological procedures. All samples were streaked onto blood agar and MacConkey agar and kept at 37 °C for 18-24 hours under aerobic conditions. After incubation, microbial growth was examined, and isolates were identified by conventional morphological and biochemical characteristics.

Pure cultures were prepared from each isolate and subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility profiles were determined with the VITEK 2 Compact system (bioMerieux, France) following the standards outlined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines.15 Gram-negative isolates were processed using GN ID and AST 405/406 cards, while Gram-positive isolates were tested using GP ID and AST 628 cards.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles were classified based on standard definitions. The categories comprised carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), ESBL producing Klebsiella spp., MRSA, and multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains, with MDR referring to isolates resistant to at least three distinct groups of antimicrobial drugs.

Inclusion criteria

Patients of any age or gender presenting with clinical signs and symptoms suggestive of SSI within 30 days of surgery or within 1 year for procedures involving prosthetic implants. Samples collected from the surgical wound site, such as wound swabs, pus, exudates, discharges, or aspirates, showing purulent discharge, erythema, swelling, or delayed wound healing; and specimens yielding significant bacterial growth on culture.

Exclusion criteria

Non-surgical wound infections (e.g., traumatic wounds, diabetic foot ulcers, burns, pressure sores) samples with mixed growth of skin commensals or insignificant bacterial growth, patients who had received systemic antibiotics for more than 48 hours before sample collection, unless infection signs persisted and repeat samples from the same patient for the same infection episode, only the first isolate was considered.

Statistical analysis

All data were recorded and analyzed utilizing Microsoft Excel.

Over the 24-month study period from August 2023 to July 2025, a total of 21,952 surgical procedures were performed across various specialties. Patients who developed postoperative signs suggestive of surgical site infection (SSI) including wound gaping, serous or purulent discharge, localized erythema, and tenderness were clinically evaluated. Relevant clinical specimens such as wound swabs, pus, aspirates, or discharge were collected and subjected to microbiological culture.

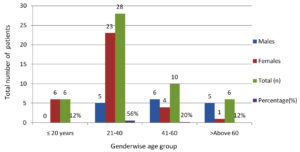

Fifty culture-positive SSI cases were recorded over the course of study period. The 21-40 years age group formed the largest proportion of cases (56%), followed by 41-60 years (20%), ≤20 years (12%), and >60 years (12%). Females were more often affected than males (68% vs. 32%). Young adult women (21-40 years) were the most frequently affected subgroup (Figure).

The highest proportion of SSIs occurred in Obstetrics & Gynecology (58%), most commonly in clean-contaminated wounds. General Surgery accounted for 18% of cases, followed by Surgical Gastroenterology (12%), Neurosurgery (6%), Orthopaedics (4%), and Cardiothoracic Surgery (2%). Dirty wounds were exclusively seen in General Surgery, while clean wounds predominated in Neurosurgery and Orthopedics (Table 1).

Table (1):

Surgical Site Infection distribution by wound classification and specialty

Speciality |

Clean (n) |

Clean contaminated (n) |

Contaminated (n) |

Dirty |

Total (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Obstetrics & Gynecology (OB&GYN) |

0 |

28 |

1 |

0 |

29 |

58% |

General Surgery |

1 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

9 |

18% |

Surgical Gastroenterology |

0 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

6 |

12% |

Neuro Surgery |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

6% |

Orthopaedics |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

4% |

Cardiothoracic Surgery (CT Surgery) |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2% |

Wound classification CDC criteria: clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, dirty/infected: with results expressed as frequency and percentage (%).16

Distribution of surgical site infections by type of surgery. Data are presented as the number and percentage of infections observed in each surgical category.

Of the 50 SSI cases, 22 patients (44%) underwent emergency surgeries, while 28 cases (56%) followed elective procedures. In Obstetrics & Gynecology, SSIs were overwhelmingly associated with emergency operations (90.9%). Conversely, all SSIs in Surgical Gastroenterology, Neurosurgery, Orthopaedics, and Cardiothoracic Surgery were after elective interventions. General Surgery cases were more evenly distributed, with 22.2% linked to emergency and 77.8% to elective procedures (Table 2).

Table (2):

Distribution of Surgical Cases by Type of Surgery (Emergency vs. Elective) and Specialty

Speciality |

Emergency (n) |

Elective Surgery (n) |

Total (n) |

Emergency (%) |

Elective (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Obstetrics & Gynecology (OB&GYN) |

20 |

9 |

29 |

90.9% |

32.1% |

General Surgery |

2 |

7 |

9 |

9.1% |

25.0% |

Surgical Gastroenterology |

0 |

6 |

6 |

0.0% |

21.4 % |

Neuro Surgery |

0 |

3 |

3 |

0.0% |

10.7% |

Orthopaedics |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0.0% |

7.1% |

Cardiothoracic Surgery (CT Surgery) |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0.0% |

3.6% |

Fifity culture positive specimens were obtained during the study period from patients with suspected SSIs. A single bacterial isolate was obtained from each of the 50 specimens. The most common pathogen was Escherichia coli 20 isolates (40%), followed by Klebsiella spp. 13 isolates (26%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6 isolates (12%). Less frequently isolated organisms included Staphylococcus aureus (8%), Acinetobacter baumannii (4%), and single isolates (2% each) of Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Enterobacter cloacae, Pluribacter spp., Serratia spp., and Proteus penneri. Gram-positive bacteria constituted 10% of the total isolates as shown in Table 3.

Table (3):

Microbial Isolates distribution (n = 50)

Microbial Isolates |

Total (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

E. coli |

20 |

40% |

Klebsiella spp. |

13 |

26% |

P. aeruginosa |

6 |

12% |

A. baumanii |

2 |

4% |

S. aureus |

4 |

8% |

S. haemolyticus |

1 |

2% |

E. cloacae |

1 |

2% |

Pluribacter spp. |

1 |

2% |

Serratia spp. |

1 |

2% |

Proteus penneri |

1 |

2% |

Among the 50 isolates, 2 (4%) were identified as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Multidrug-resistance (MDR) defined as resistance to at least three antimicrobial classes was observed in 4 isolates (8%), including E. coli, Klebsiella spp., P. aeruginosa, and A. baumannii. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production was detected in 7 isolates (14%), occurring most frequently in Klebsiella spp. (30.8%) and E. coli (15%). Carbapenem resistance was also seen in 7 isolates (14%), predominantly in E. coli (20%) and Klebsiella spp. (23.1%) as shown in Table 4.

Table (4):

Patterns of Antimicrobial Resistance among Isolates

Microbial Isolates |

MRSA (n%) |

MDR (n%) |

ESBL (n%) |

Carbapenem Resistant (n%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

E. coli |

0 |

1 (5%) |

3 (15%) |

4 (20%) |

Klebsiella spp. |

0 |

1 (7.7%) |

4 (30.8%) |

3 (23.1%) |

P. aeruginosa |

0 |

1 (16.7%) |

0 |

0 |

A. baumanii |

0 |

1 (50%) |

0 |

0 |

S. aureus |

2 (50%) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

S. haemolyticus |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

E. cloacae |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Pluribacter spp. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Serratia spp. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Proteus penneri |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Total |

2 |

4 (8%) |

7 (14%) |

7 (14%) |

E. coli isolates exhibited the highest responsiveness to tigecycline (90%), then by amikacin (80%) and gentamicin (75%). Moderate susceptibility (60%) was noted for imipenem, meropenem, colistin, and fosfomycin. Klebsiella spp. demonstrated maximum susceptibility to tigecycline (76.9%), followed by cefoperazone/sulbactam (61.5%) and ertapenem (53.8%). Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates were most susceptible to amikacin and meropenem (83.3% each). A. baumannii showed complete susceptibility (100%) to cefoperazone/sulbactam, colistin, tigecycline, and minocycline. S. aureus isolates exhibited full susceptibility (100%) to tetracycline, teicoplanin, and rifampicin, with vancomycin and gentamicin showing 75% effectiveness (Tables 5-7).

Table (5):

Antibiotic Sensitivity Pattern of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. Isolates

Antibiotics |

E. coli (n%) |

Klebsiella spp. (n%) |

|---|---|---|

Gentamicin |

75% |

69.2% |

Netilmicin |

5% |

0% |

Chloramphenicol |

5% |

0% |

Ciprofloxacin |

15% |

23.1% |

Amoxicillin /clavulanic acid |

25% |

7.7% |

Doxycycline |

5% |

0% |

Ceftriaxone |

15% |

23.1% |

Ceftizoxime |

5% |

0% |

Amikacin |

80% |

53.8% |

Cefoperazone /sulbactam |

55% |

61.5% |

Cefuroxime |

10% |

7.7% |

Tobramycin |

5% |

0% |

Piperacillin /tazobactam |

45% |

38.5% |

Cefepime |

25% |

30.8% |

Imipenem |

60% |

38.5% |

Polymyxin |

5% |

0% |

Ertapenem |

45% |

53.8% |

Cefuroxime axetil |

10% |

7.7% |

Colistin |

60% |

30.8% |

Tigecycline |

90% |

76.9% |

Minocycline |

20% |

7.7% |

Meropenem |

60% |

38.5% |

Tetracycline |

5% |

0% |

Fosfomycin |

60% |

38.5% |

Ceftazidime/ avibactam |

5% |

0% |

ceftolozane /tazobactam |

0% |

0% |

cefoxitin |

5% |

0% |

Co-trimoxazole |

35% |

53.8% |

Note. The CLSI guidelines were applied for susceptibility testing, with isolates categorized as intermediate being regarded as resistant for analytical purposes.17

Table (6):

Antibiotic Sensitivity Pattern of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates

Antibiotics |

Pseudomonas spp. |

Acinetobacter spp. |

|---|---|---|

Levofloxacin |

50% |

50% |

Gentamicin |

0% |

50% |

Ciprofloxacin |

50% |

50% |

Ceftazidime |

33.33% |

50% |

Amikacin |

83.3% |

50% |

Cefoperazone /sulbactam |

33.3% |

100% |

Piperacillin tazobactam |

33.3% |

50% |

Cefepime |

50% |

50% |

Imipenem |

50% |

50% |

Colistin |

50% |

100% |

Tigecycline |

0% |

100% |

Minocycline |

0% |

100% |

Meropenem |

83.3% |

50% |

Co-trimoxazole |

0% |

50% |

Note. The CLSI guidelines were applied for susceptibility testing, with isolates categorized as intermediate being regarded as resistant for analytical purposes.17

Table (7):

Antibiotic Sensitivity Pattern of Staphylococcus aureus Isolates

Staphylococcus aureus |

Antibiotic sensitivity |

|---|---|

Vancomycin |

75% |

Gentamicin |

75% |

Nitrofurantoin |

50% |

Linezolid |

25% |

Tigecycline |

50% |

Tetracycline |

100% |

Teicoplanin |

100% |

Rifampicin |

100% |

Co-trimoxazole |

25% |

Note. The CLSI guidelines were applied for susceptibility testing, with isolates categorized as intermediate being regarded as resistant for analytical purposes.17

The present study investigated the prevalence of surgical site infections (SSIs) in a tertiary care hospital over a two-year period, characterized the microbiological profiles of the pathogens involved, analyzed their antimicrobial resistance patterns, and underscored the role of hospital-acquired infection (HAI) surveillance and timely antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing SSI incidence. The overall SSI burden in our study was 50 culture-confirmed cases among 21,952 surgical procedures, corresponding to a prevalence of approximately 0.23%. This relatively low prevalence contrasts with higher SSI rates reported in other tertiary care hospitals across India, where prevalence ranges widely between 2% and 18.6% depending on surgical specialty, case mix, and study methodology.5,18-23 Variability in reported SSIs may also reflect differences in CDC definition adherence, surveillance methods, infection control policies, and perioperative care protocols. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that effective infection prevention measures, strict adherence to prophylactic antibiotic protocols, and active HAI surveillance may have contributed to the comparatively lower rate observed.

A striking finding was the predominance of SSIs among young adult females (21-40 years), particularly in the obstetrics and gynecology (OB&GYN) department, which contributed 58% of all cases. The high proportion from OB&GYN is consistent with previous data indicating that obstetric surgical procedures, especially cesarean sections performed in emergency settings, carry elevated infection risks due to prolonged labor, rupture of membranes, and contamination during emergent interventions.3,24,25 Our data showed 90.9% of OB&GYN SSIs occurred after emergency surgeries, reinforcing the need for enhanced adherence to antibiotic prophylaxis timing and improved surgical asepsis in urgent procedures.

The majority of SSIs arose from clean-contaminated wounds, particularly in OB&GYN and surgical gastroenterology, a pattern consistent with global literature.26 Clean wounds, which predominated in neurosurgery and orthopaedics in our cohort, exhibited lower infection rates, consistent with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN).27 Dirty wounds, confined to general surgery in our study, predictably carried the highest inherent infection risk.

Escherichia coli (40%) was the most frequent isolate, followed by Klebsiella spp. (26%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12%). This predominance of Gram-negative organisms mirrors recent SSI surveillance data from Indian and international studies, where Enterobacterales have overtaken S. aureus as the major pathogens.28,29 The S. aureus proportion (8%) aligns with other Indian series.30

Antimicrobial resistance patterns in our sample raise major concerns. Notably 14% of isolates were ESBL producers and 14% were carbapenem-resistant, most notably among E. coli and Klebsiella spp. These findings are in line with WHO’s global priority list calling for urgent research and new drug development against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales.31 The MRSA rate among S. aureus (50%) was higher than some national averages reported from India.32 calling for strengthened infection prevention measures and antibiotic stewardship.

Our results reaffirm the value of robust SSI surveillance programs and targeted interventions in high-risk specialties. Evidence shows that adherence to proper timing of prophylactic antibiotics within 60 minutes before incision significantly reduces SSI rates in both elective and emergency procedures. Hospital policies ensuring compliance, supported by periodic audit and feedback, are essential for sustaining low infection rates.33,34

Limitations

These findings of a single-center retrospective study at a tertiary hospital may not be generalizable to other settings. Only in-hospital, culture-confirmed SSIs were included, possibly underestimating true prevalence. No molecular resistance typing was performed. Late SSIs post-discharge may have been missed.

Multi-center surveillance with molecular typing of resistant isolates, need-based evaluation of bundle-based SSI prevention programs and more targeted interventions in high-risk surgical specialties should constitute the focus of future research.

The low SSI prevalence in this study, compared with Indian averages, coincides with intensive HAI surveillance and may reflect good prophylaxis adherence. However, the predominance of Gram-negative pathogens and significant multidrug-resistance highlight the urgent need for sustained infection control and antimicrobial stewardship.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) vide approval letter number NRIAS/IEC/MICRO/017/ 2025.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- Birhanu Y, Endalamaw A. Surgical site infection and pathogens in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Saf Surg. 2020;14:7.

Crossref - Kundarapu V, Shelke A, Priya P, Mishra S, Chauhan R, Dhingra S. Assessment of surgical site infections with antimicrobial resistance among cancer patients at a tertiary care hospital: a prospective study. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2025;34:102103.

Crossref - Amenu D, Belachew T, Araya F. Surgical site infection rate and risk factors among obstetric cases of Jimma University Specialized Hospital, southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2011;21(2):91-100.

Crossref - Boru K, Aliyo A, Daka D, Gamachu T, Husen O, Solomon Z. Bacterial surgical site infections: prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, and associated risk factors among patients at Bule Hora University Teaching Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. IJID Reg. 2025;14:100565.

Crossref - Hemmati H, Hasannejad-Bibalan M, Khoshdoz S, et al. Two-year study of prevalence and antibiotic resistance pattern of Gram-negative bacteria isolated from surgical site infections in the north of Iran. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):383.

Crossref - Pipaliya B, Shah P, Vegad M, Soni S, Agrawal A, Goswami A. Prevalence of SSI in Post Operative Patients in Tertiary Health Care Hospital. Natl J Integr Res Med. 2017;8:1-8.

Crossref - Abdulqader HH, Saadi AT. The distribution of pathogens, risk factors, and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns among post-surgical site infections in Rizgari Teaching Hospital in Erbil/Kurdistan Region/Iraq. J Duhok Univ. 2019;22:1-10.

Crossref - Wenzel RP. Surgical site infections and the microbiome: an updated perspective. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40(5):590-596.

Crossref - Gallo J, Nieslanikova E. Prevention of prosthetic joint infection: from traditional approaches towards quality improvement and data mining. J Clin Med. 2020;9(7):2190.

Crossref - Mathur P, Singh S. Multidrug resistance in bacteria: a serious patient safety challenge for India. J Lab Physicians. 2013;5(1):5-10.

Crossref - Eshaghi M, Bibalan MH, Pournajaf A, Gholami M, Talebi M. Detection of new virulence genes in mecA-positive Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical samples: the first report from Iran. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2017;25(6):310-313.

Crossref - Omoyibo EE, Oladele AO, Ibrahim MH, Adekunle OT. Antibiotic susceptibility of wound swab isolates in a tertiary hospital in Southwest Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2018;17(3):110-116.

Crossref - Sydnor ERM, Perl TM. Hospital epidemiology and infection control in acute care settings. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(1):141-173.

Crossref - Siwakoti S, Subedi A, Sharma A, Baral R, Bhattarai NR, Khanal B. Incidence and outcomes of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria infections in intensive care unit from Nepal—a prospective cohort study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:114.

Crossref - BioMerieux VITEK 2 Instrument User Manual. Durham, NC: BioMerieux Clinical Diagnostics; 2015. Available at: https://www.manualslib.com/manual/2957819/Biomerieux-Vitek-2.html. Accessed July 1, 2025

- Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13(10):606-608.

Crossref - Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 34th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2024. Accessed July 2, 2025.

- Lilani SP, Jangale N, Chowdhary A, Daver GB. Surgical site infection in clean and clean-contaminated cases. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2005;23(4):249-252.

Crossref - Kamat US, Fereirra AMA, Kulkarni MS, Motghare DD. A prospective study of surgical site infections in a teaching hospital in Goa. Indian J Surg. 2008;70(3):120-124.

Crossref - Anvikar AR, Deshmukh AB, Karyakarte RP, et al. One-year prospective study of 3,280 surgical wounds. Indian J Med Microbiol. 1999;17(3):129-132.

- Misha G, Chelkeba L, Melaku T. Incidence, risk factors and outcomes of surgical site infections among patients admitted to Jimma Medical Center, South West Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;65:102247.

Crossref - Chada CKR, Kandati J, Ponugoti M. A prospective study of surgical site infections in a tertiary care hospital. International Surgery Journal, 2017;4(6): 1945-1952.

Crossref - Baker AW, Dicks KV, Durkin MJ, et al. Epidemiology of surgical site infection in a community hospital network. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(5):519-526.

Crossref - Opoien HK, Valbo A, Grinde-Andersen A, Walberg M. Post-cesarean surgical site infections according to CDC standards: rates and risk factors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(9):1097-1102.

Crossref - Smaill FM, Grivell RM. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD007482.

Crossref - Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(4):250-278.

Crossref - Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care–associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(5):309-332.

Crossref - Mahesh CB, Shivakumar S, Suresh BS, Chidanand SP, Vishwanath Y. A prospective study of surgical site infections in a teaching hospital. J Clin Diagn Res. 2010;4(5):3114‑3119.

Crossref - World Health Organization. Global Guidelines for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475 Accessed July 2, 2025

- Rajkumari N, Sharma K, Mathu P, Subodh Kumar, Gupta A. A study on surgical site infections after trauma surgeries in a tertiary care hospital in north India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140(5):691-694.

- World Health Organization. Global Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. Accessed July 2, 2025.

- Indian Council of Medical Research. Annual Report January 2021 to December 2021. Antimicrobial Resistance Research and Surveillance Network. New Delhi, India: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2021. https://icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/reports/AMRSN_Annual_Report_2021.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2025.

- Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(3):195-283.

Crossref - Allegranzi B, Zayed B, Bischoff P, et al. New WHO recommendations on intraoperative and postoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(12):e288-e303.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.