ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

This study evaluated the antibacterial efficacy, biofilm inhibition capabilities, and synergistic potential of copper oxide nanoparticles (CuONPs) against biofilm-forming Klebsiella pneumoniae, uniquely exploring previously unexplored mechanisms, particularly their influence on critical biofilm-associated gene regulatory networks. CuONPs were characterized by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM), with antibacterial activity assessed through minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC). Synergistic effects with antibiotics (Clindamycin, Bactrim, and Imipenem) were evaluated using disc diffusion methods, while biofilm inhibition was quantified via microtiter plate assays and bacterial reduction rates were assessed by time-kill kinetics. Additionally, qRT-PCR was employed to analyze expression changes of biofilm-related genes (luxS, mrkA, fimA, rcsA, and kpa). Results demonstrated substantial antibacterial activity of CuONPs against K. pneumoniae with consistent MIC and MBC values at 50 mg/ml and 100 mg/ml, respectively, significant antibiotic synergism with reductions in required dosages by 40%-60%, notable biofilm impairment up to 80%, rapid bacterial decline within 2-4 hours, and significant downregulation of biofilm-associated genes mrkA, fimA, and luxS (up to 5-fold). In conclusion, CuONPs exhibit pronounced antibacterial and anti-biofilm properties, significantly enhanced by antibiotic synergy, providing novel insights into biofilm regulatory mechanisms and highlighting their clinical potential for treating multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae infections.

Copper Oxide Nanoparticles (CuONPs), Antibacterial Activity, Biofilm Inhibition, Antimicrobial Resistance

The emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) presents considerable difficulties to global public health, worsening the management of infectious illnesses and increasing morbidity and death rates globally.1 Among the major AMR pathogens, Klebsiella pneumoniae is particularly alarming. This Gram-negative bacterium is notorious for its ability to form robust biofilms and its high resistance to multiple antibiotics, making infections extremely difficult to eradicate clinically.2 Biofilm formation enables K. pneumoniae to persist on medical devices such as catheters and ventilators, as well as on host epithelial tissues. Within the biofilm, bacteria are protected by an extracellular matrix that facilitates long-term survival, horizontal gene transfer, and evasion of host immune responses, leading to chronic and recurrent infections often associated with treatment failure and elevated mortality rates.3

K. pneumoniae also exhibits a complex and evolving resistance profile. The pathogen has developed resistance to β-lactams, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones, primarily through mechanisms such as extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), carbapenemases, efflux pumps, and capsular regulation.4 The antibiotics used in this study-imipenem, cotrimoxazole, and clindamycin-were chosen to reflect both clinical importance and scientific rationale. Imipenem was included because carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae is a global crisis, cotrimoxazole remains widely prescribed for urinary and respiratory infections despite increasing resistance, and clindamycin was tested to evaluate whether CuONPs could extend its spectrum against Gram-negative bacteria through synergistic effects. These antibiotics were selected based on clinical guidelines, local resistance concerns, and prior studies reporting enhanced efficacy when combined with nanoparticles.5,6

The genetic targets selected in this work represent key regulators of adhesion, biofilm formation, and virulence in K. pneumoniae. The fimA gene encodes type I fimbriae critical for epithelial adhesion, while mrkA encodes type III fimbriae that mediate strong attachment to medical devices and are essential for mature biofilm formation.7 The kpa gene contributes to fimbrial assembly and surface colonization, and rcsA regulates capsule biosynthesis, thereby strengthening biofilm structure and protecting cells against antimicrobial stress.3,8 Finally, luxS is a quorum-sensing gene central to intercellular communication, regulation of virulence factors, and coordination of biofilm behavior.9 These genes are frequently expressed in resistant clinical strains, making them ideal molecular markers for understanding the antibiofilm impact of CuONPs.

Recent advancements in nanotechnology have provided new avenues to combat resistant pathogens. Copper oxide nanoparticles (CuONPs), in particular, have attracted attention due to their high surface area-to-volume ratio, enhanced reactivity, and strong antibacterial properties. Their mechanisms of action include the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), disruption of cell membranes, and interference with bacterial metabolism.5,10,11 However, despite increasing reports of their antibacterial and antibiofilm potential, little is known about how CuONPs influence the genetic regulatory networks underpinning biofilm formation in K. pneumoniae.

This research seeks to fill this significant gap by combining phenotypic testing with qRT-PCR analysis of genes related to biofilms. This approach offers a new understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which CuONPs impede biofilm development and improve antibiotic effectiveness. The results not only demonstrate the therapeutic efficacy of CuONPs against multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae but also enhance the overall comprehension of nanoparticle-bacteria interactions at the genetic level. The study’s dual emphasis on functional antibacterial effects and gene regulation differentiates it, addressing a significant gap in the literature and providing therapeutically pertinent techniques for managing persistent infections.

Preparation and characterization of copper oxide nanoparticles

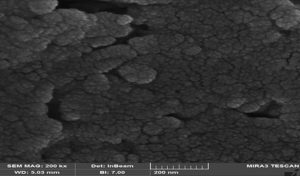

Copper oxide nanoparticles were synthesized chemically by a modified method based on Awaad et al., which entails the interaction of copper chloride (CuCl2) with sodium hydroxide (NaOH) at pH 12. The resulting nanoparticles were subjected to centrifugation, washing, and drying, and then synthesized at several concentrations (200-3.125 mg/ml) for experimental purposes. The operational concentration range of 200-3.125 mg/mL for CuONPs was determined based on published studies assessing nanoparticle antimicrobial efficacy.12,13 alongside preliminary optimization experiments conducted in our laboratory to ascertain doses that elicited quantifiable antibacterial and antibiofilm effects without inducing significant aggregation or instability of the suspensions. This range guaranteed comparability with previous studies and biological significance for in vitro experiments. The nanoparticle suspensions were vortexed and sonicated to achieve uniformity.14 Characterization was conducted utilizing Confocal Scanning Probe Microscopy (CSPM), Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), and Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM), confirming that the CuONPs were predominantly spherical, uniformly distributed, displayed a smooth morphology, exhibited minimal aggregation, and were suitable for biological and antibacterial assessments. An innovative component of our methodology encompasses comprehensive visualization and quantitative evaluation of nanoparticle-biofilm interactions, especially using sophisticated FE-SEM methods. The study assessed the entrapment efficiency of nanoparticles using UV-Vis spectrophotometry, revealing a 2.4% efficiency. This is sufficient for generating stable nanoparticle suspensions for antimicrobial assays, despite low theoretical copper content. Controls included untreated K. pneumoniae cultures and conventional antibiotic discs. Parallel assays with vehicle-only preparations showed no inhibitory activity, confirming the effects were solely due to active CuONPs.

The culture of K. pneumoniae

The study necessitates the acquisition of biofilm-producing strains of Gram-negative bacteria to examine the impact of copper oxide nanoparticles on biofilm development. The reference bacterial strain Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603, recognized for its biofilm-forming capability, will be obtained from Biomedia SPD Scientific. The reference strain has been documented in prior investigations to demonstrate moderate-to-strong biofilm formation under conventional laboratory settings.3,4 This study experimentally established the strain’s biofilm generation by the crystal violet microtiter plate assay conducted before treatment, revealing a robust baseline biofilm density in comparison to negative controls. This confirmation guaranteed that the following antibiofilm tests with CuONPs were performed on a biofilm-capable strain, enhancing the therapeutic significance of the results. The strain will be supplied as freeze-dried cultures, which will then be meticulously rehydrated according to the supplier’s comprehensive instructions to guarantee the viability and integrity of the microorganisms. K. pneumoniae was grown on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA), Mueller-Hinton agar and broth from (Oxoid, Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK), which were used for susceptibility testing, chosen for their nutritional content, which facilitates optimum development and homogeneity of colonies. The bacteria were cultured at 35-37 °C under typical atmospheric conditions for 18-24 hours to promote optimal bacterial growth and initial biofilm formation.

Antimicrobial Activity

The agar diffusion method (Kirby-Bauer method)

The agar diffusion technique was used to assess the antibacterial efficacy of CuONPs against K. pneumoniae, as described by Hudzicki.15 Mueller-Hinton agar plates infected with K. pneumoniae had wells filled with differing quantities of CuONPs (200-3.125 mg/ml). Following an initial incubation at 5-8 °C for 2-4 hours to facilitate nanoparticle diffusion, plates were then incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C. The antibacterial activity was assessed by measuring the width of inhibition zones around each well, with findings compared to positive and negative controls.

Determination of the (MIC) and (MBC) of CuONPs

The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of CuONPs against K. pneumoniae were determined using the dilution tube method.16 Various concentrations of CuONPs (from 200 mg/ml to 3.125 mg/ml) were prepared in Mueller-Hinton broth. All media were obtained from Oxoid (Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK), inoculated with standardized bacterial suspensions matching a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard, and incubated at 37 °C for 18-24 hours. Tubes showing no bacterial growth were further tested by plating onto tryptic soy agar to confirm bactericidal activity. Experiments were performed in triplicate to guarantee precision and repeatability, adhering to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria (CLSI, 2021. M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 31st Edition). All assays incorporated suitable controls: (i) negative control tubes with uninoculated Mueller–Hinton broth to verify sterility and exclude contamination, and (ii) positive control tubes containing bacterial inoculum devoid of CuONPs to establish baseline growth and validate assay efficacy.

The synergistic effect of CuNPs with broad-spectrum antibiotics

The combination antibacterial efficacy of CuONPs and antibiotics (Bactrim, Clindamycin, and Imipenem) against K. pneumoniae was assessed by the disc diffusion technique as described by Alnuaimi et al and Murugn.17,18 Antibiotic discs and CuONPs solutions were produced separately and kept correctly. Standardized bacterial suspensions were injected onto Tryptic Soy Agar plates to create a homogenous bacterial lawn. Antibiotic discs, nanoparticle solutions, and their mixtures were used on these plates. Following incubation at 36 ± 1 °C for 24 hours, inhibition zones were quantified to evaluate antimicrobial effectiveness. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate to ensure precision and repeatability, to identify synergistic interactions for possible therapeutic uses against resistant bacteria.

Evaluation of biofilm production by K. pneumoniae in exposure to CuONPs

The impact of CuONPs on biofilm development by K. pneumoniae was evaluated utilizing the conventional microtiter plate (MTP) technique with crystal violet staining.19 Bacterial cultures were calibrated to 0.5 McFarland (about 1 × 106 CFU/mL) and injected into sterile 96 well flat-bottom plates containing Mueller-Hinton broth augmented with CuONPs at concentrations between 200 and 3.125 mg/mL. Untreated bacterial cultures acted as positive controls (highest biofilm development), whilst wells containing only medium functioned as negative controls. Following a 24-hour incubation at 37 °C, non-adherent cells were eliminated using PBS washing, and the wells were subsequently stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 minutes. The surplus stain was removed, and the bound dye was dissolved in 95% ethanol. Optical density was quantified at 570 nm (OD570) with a microplate reader. Values were adjusted by subtracting the blank (media-only wells) to standardize for background absorbance. Two experimental setups were conducted: (i) CuONPs were introduced concurrently with bacterial inoculation to assess biofilm inhibition, and (ii) CuONPs were administered after 24 hours of incubation to evaluate biofilm eradication. Each condition was evaluated in duplicate wells and replicated across three different experiments. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance relative to controls was evaluated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test in GraphPad Prism. The selected concentration range of CuONPs (200-1.56 mg/mL) was determined based on previous studies12,13 and initial optimization tests that confirmed detectable effects without precipitation or instability.

Time-kill curve method for CuONPs

Time-kill curve experiments were conducted to assess the bactericidal efficacy of CuONPs against Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603, the method was used as described by Alshareef20 and Foerster et al.21 with modifications. Bacterial suspensions were calibrated to 0.5 McFarland (about 1 × 106 CFU/mL) and introduced into sterile test tubes containing Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) augmented with CuONPs at varying concentrations (0.5×, 1×, and 2× MIC). Cultures were maintained at 37 °C, with aliquots extracted at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 hours. At each time point, samples were serially diluted (10-1 to 10-4) in sterile saline and subsequently plated on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA). Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours, after which colony-forming units (CFU/mL) were counted. Bacterial survival was quantified as log10 CFU/mL over time to produce time-kill curves. Untreated bacterial cultures functioned as negative controls. All experiments were conducted in duplicate to guarantee repeatability.

Quantification of biofilm gene expression before and after treatment with CuONPs

RNA extraction of bacteria

Total RNA was isolated from Klebsiella pneumoniae cultures subjected to CuONPs and untreated controls using a commercial RNA extraction kit (Monarch® Total RNA Miniprep Kit, New England Biolabs, USA), following the manufacturer’s procedure. The purity and concentration of RNA were assessed using a microvolume spectrophotometer.

cDNA synthesis

RNA, about 58.2 ng per sample, was reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) with the SensiFAST cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bioline, UK), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The final cDNA quantities used for subsequent qPCR assays were standardized to about 2.91 ng/µL.

Primer formulation and quantitative PCR protocol

Primers aimed at quorum sensing genes (luxS, rcsA) and fimbriae genes (kpa, mrkA, fimA) were developed with Primer Express software or obtained from sequences in published literature. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was conducted with a 2x qPCRBIO SyGreen Mix Separate-ROX (PCR Biosystems, UK). Each 20 µL reaction included 10 µL of SyGreen Mix, 0.4 µL of each primer (forward and reverse, 10 µM each), 0.25 µL of cDNA template (final concentration 0.73 ng), and nuclease-free water. The PCR cycling protocol included an initial activation phase at 95 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 seconds, primer-specific annealing for 20 seconds (with fluorescence measurement), and extension at 72 °C for 30 seconds. The melting curve analysis (74-95 °C) validated the specificity of the PCR products. Negative controls were included, and experiments were performed in triplicate.

A novel aspect of our approach includes a comprehensive molecular assessment of biofilm-associated gene regulatory responses using quantitative real-time PCR, giving us extensive knowledge of the genetic mechanisms underlying nanoparticle-bacterial interactions. A reference gene (rpoB), along with primers for luxS, mrkA, fimA, rcsA, and kpa. All expression levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene rpoB for exact quantification. were created using published sequences or acquired from GenBank. Primer efficiency and specificity were validated by standard curves. The details of all primers used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table (1):

Primer sequences and characteristics of target genes and the housekeeping gene (rpoB) used for qPCR analysis in K. pneumoniae

Gene and accession number |

Sequence (5’→3′) F (sense), R (antisense) |

GC (%) (F / R) |

Slope |

Efficiency (%) |

R2 |

Annealing Temp. (°C) |

Primers Concen. (nM) |

Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

LuxS NC_007795.1 |

F: GGAACTGGGAGAAATTATCGA R: GCACTGGTAGACGTTAGAGC |

42.9 52.6 |

-3.34 |

99.03 |

0.987 |

53.5 |

250 |

150 |

mrkA CP000647.1 |

F: CCCTGACTGAAGTTAAAGCGG R: CGTCACTGTTATCAGGCACG |

52.4 52.6 |

-3.16 |

107.21 |

0.982 |

52.5 |

250 |

298 |

fimA CP000647.1 |

F: TGATTGGTGTTGTGTCGGTC R: CTGGATGGAAGAAACCGACG |

50.0 55.0 |

-3.50 |

92.95 |

0.991 |

52.5 |

250 |

300 |

rcsA CP000647.1 |

F: ATTTGCTGCAGTATACCCGGTTGG R: AGATCCGCCATTGATACGAGTACC |

50.0 52.2 |

-3.40 |

96.65 |

0.97 |

57.3 |

250 |

400 |

kpa CP000647.1 |

F: GCCGATACGCTACATTATAAC R: CAGGTTCGCGATTTATTATTCC |

42.9 40.9 |

-3.30 |

100.89 |

0.993 |

52.0 |

250 |

250 |

STD rpoB for K. pneumoniae MGH 78578 |

F: CGCTGTCTGAGATTACGCAC R: CGTCAGTAACCACACCGTTG |

55.0 55.0 |

-3.55 |

91.06 |

0.983 |

59.8 |

500 |

108 |

Quantification and analysis of gene expression

Gene expression levels were assessed using the comparative ִִCq technique to ascertain the relative quantification of target genes, normalized against appropriate reference genes. Data were statistically analyzed using bespoke software with specified methods, guaranteeing precise and repeatable outcomes.

Laboratory equipment and quality control

Experiments were performed using calibrated equipment, including a BINDER incubator (Germany), Hettich Universal 320R centrifuge (Germany), and Thermo Scientific GENESYS 10S spectrophotometer (USA). Sterility of media was confirmed by uninoculated controls, and the standard reference strain (S. aureus ATCC 29213) was included to ensure assay validity.

Statistical data analysis

Statistical analysis will be performed using GraphPad Prism, version 10.4.0. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett’s test will be used for analysing differences between OD values. A value of p < 0.0001 will be considered statistically significant.

Characterization of CuONPs

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) of CuONPs

FE-SEM characterization validated the morphological characteristics of the produced CuONPs (Figure 1). The nanoparticles were primarily spherical, evenly dispersed, displayed smooth surfaces, and exhibited minimal aggregation. The particle size of approximately 55.98 nm corresponded with the findings from AFM and CSPM analyses, validating the suitability of the CuONPs for biological testing. No antibacterial or antibiofilm effects were seen in the vehicle-only control groups, confirming that the inhibitory activity was exclusively due to the CuONPs and not the carrier medium.

Figure 1. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) micrograph of CuONPs showing predominantly spherical morphology, smooth surface features, minimal aggregation, and uniform distribution with an average size of ~55.98 nm. Scale bar = 500 nm

Antimicrobial activity of CuONPs against K. pneumoniae

The antibacterial effectiveness of CuONPs against K. pneumoniae was thoroughly evaluated using the agar diffusion technique, demonstrating a clear, concentration-dependent suppression of bacterial growth (P < 0.0001). The maximum tested concentration (200 mg/ml) yielded the most extensive inhibitory zone (21-22 mm), while lesser doses exhibited correspondingly reduced zones 100 mg/ml (19-20 mm), 50 mg/ml (16-18 mm), 25 mg/ml (14-16 mm), 12.5 mg/ml (12-14 mm), 6.25 mg/ml (10-12 mm), and 3.125 mg/ml (8-10 mm) (Figure 2). The bar graph quantifies this data by illustrating the inhibition zone widths for each concentration. Bacterial growth was significant in untreated controls; however, CuONPs at doses of 12.5 mg/ml and above demonstrated pronounced antibacterial efficacy, with almost total bacterial elimination seen at 100 and 200 mg/ml. The strong antibacterial impact is due to the production of Cu2+ ions, which damage bacterial membranes, deactivate vital enzymes, and hinder DNA replication, finally leading to cell lysis.10,12,22 Moreover, optical density studies at 600 nm validated a dose-dependent decrease in bacterial viability, with statistically significant decreases seen at higher concentrations. Furthermore, CuONPs significantly impeded biofilm formation, a crucial element in chronic and multidrug-resistant infections, highlighting their potential as efficient antimicrobial agents against resistant K. pneumoniae strains.12 These results align with other studies validating the extensive antibacterial and antibiofilm properties of CuONPs.13

Figure 2. (A) Agar diffusion assay showing visible inhibition zones around wells containing increasing concentrations of CuONPs (3.125-200 mg/ml), illustrating a clear concentration-dependent antibacterial effect. (B) Bar graph quantifying the diameter of inhibition zones, with the highest activity observed at 200 mg/ml and decreasing progressively with lower concentrations (P < 0.0001). (C) Effect of CuONPs on bacterial viability measured by optical density (OD600), showing significant growth inhibition at concentrations ≥12.5 mg/ml, with near-complete inhibition at 100 and 200 mg/ml. Data are presented as mean ± SD; **** indicates P < 0.0001 compared to the untreated control

Determination of the MIC and MBC of CuONPs

The antibacterial effectiveness of CuONPs against K. pneumoniae was evaluated by measuring the MIC and MBC. The MIC was determined to be 50 mg/ml, while the MBC was 100 mg/ml, yielding a MIC/MBC ratio of 0.5. Ratios under 1 signify potent bactericidal efficacy, indicating that CuONPs efficiently eradicate bacteria rather than just suppressing their proliferation.23 The significant effectiveness against K. pneumoniae underscores the potential of CuONPs as a formidable antibacterial agent, particularly efficient against Gram-negative bacteria owing to their distinctive interaction with bacterial cell structures.

The Synergistic Effect of CuONPs with IPM, COT, and CD Against K. pneumoniae

The antibacterial efficacy of CuONPs (50 mg/mL), in combination with three antibiotics, imipenem (IPM), cotrimoxazole (COT), and clindamycin (CD), was evaluated against K. pneumoniae using the agar diffusion method. Individually, CuONPs exhibited notable antibacterial activity, with inhibition zones averaging 16.00-16.33 mm, while IPM and COT alone produced slightly smaller zones (14.67 mm each), all significantly larger than the untreated control (p < 0.0001). When combined, CuONPs and IPM yielded an inhibition zone of 32.67 mm, and CuONPs with COT resulted in an even larger zone of 37.00 mm, both demonstrating a statistically significant synergistic enhancement over monotherapies (p < 0.0001). In contrast, while CD alone showed negligible antibacterial activity (p > 0.9999), its combination with CuONPs produced a substantially increased inhibition zone of 30.17 mm (p < 0.0001), indicating a synergistic effect despite clindamycin’s limited standalone efficacy. The 95% confidence intervals confirmed these results, affirming the synergistic antibacterial potential of CuONPs when used in conjunction with conventional antibiotics against multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Synergistic antibacterial effects of (CuONPs, 50 mg/ml) combined with different antibiotics against K. pneumoniae. (A,B) CuONPs combined with imipenem (IPM) showed a significantly enhanced zone of inhibition compared to either agent alone (P < 0.0001). (C,D) A similar synergistic effect was observed for CuONPs combined with cotrimoxazole (COT), with the combination showing greater antibacterial activity than individual treatments. (E,F) Combination of CuONPs with clindamycin (CD) showed no significant difference compared to clindamycin alone, indicating a lack of synergistic effect (ns)

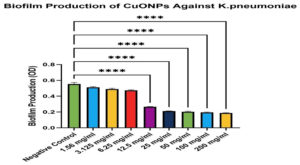

Effect of CuONPs on Biofilm Production Against K. pneumoniae

The experimental findings demonstrated a distinct dose-dependent inhibitory impact of CuONPs on the biofilm development of K. pneumoniae. Lower dosages (1.56-6.25 mg/mL) exhibited moderate decreases in biofilm biomass (71.3%-89.9% biofilm development relative to control), indicating limited antibiofilm efficacy. Conversely, higher doses (12.5-200 mg/mL) markedly decreased biofilm development, with the most pronounced effects seen between 25-200 mg/mL, resulting in roughly 33.8%-48.2% biofilm formation (p < 0.0001). These results underscore CuONPs as effective antibiofilm agents, particularly at elevated dosages, with potential therapeutic significance for managing chronic K. pneumoniae infections (Table 2 and Figure 4). The strain’s strong biofilm-forming potential enhances the credibility of the antibiofilm findings, since it closely resembles the biofilm-related persistence seen in clinical isolates. Despite variability across clinical strains, employing a validated biofilm-proficient reference strain guarantees that the observed antibiofilm actions of CuONPs are pertinent to pathogenic K. pneumoniae found in healthcare environments.3,4

Table (2):

Biofilm Production of CuONPs Against K. pneumoniae

Concen. of CuONPs |

KP + CuONPs % |

Biofilm Production |

|---|---|---|

Negative Control |

100% |

Strong biofilm former |

200 mg/ml |

33.8% |

Non-biofilm former |

100 mg/ml |

35.2% |

Non-biofilm former |

50 mg/ml |

36.7% |

Non-biofilm former |

25 mg/ml |

38.2% |

Non-biofilm former |

12.5 mg/ml |

48.2% |

Non-biofilm former |

6.25 mg/ml |

71.3% |

Weak biofilm former |

3.125 mg/ml |

84.8% |

Weak biofilm former |

1.56 mg/ml |

89.9% |

Weak biofilm former |

Figure 4. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test showed a significant reduction in biofilm compared to the negative control (P < 0.0001). Results are shown as mean ± SEM, with error bars representing standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments (n = 3)

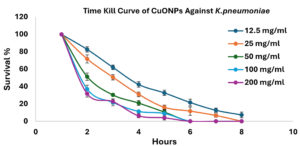

Demonstration of the time kill curve of CuNPs against K. pneumoniae

The time-kill curve analysis revealed a distinct concentration-dependent bactericidal action of CuONPs on K. pneumoniae. Elevated doses (200 mg/ml and 100 mg/ml) rapidly reduced bacterial viability, attaining almost total elimination within 6 hours. Reduced doses (50, 25, and 12.5 mg/ml) exhibited reduced bacterial reduction rates, with the lowest dosage (12.5 mg/ml) permitting the survival of some viable bacteria even after 8 hours. These results corroborate prior studies, highlighting the significant antibacterial efficacy of CuONPs at elevated dosages (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM), with error bars representing the standard deviation (SD) from three independent biological replicates (n = 3)

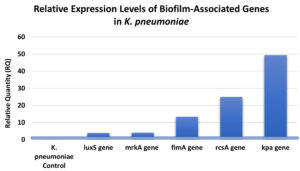

Quantification of biofilm gene expression using the qRT-PCR

Relative expression levels of the luxS, mrkA, fimA, rcsA, and kpa Genes in K. pneumoniae treated with CuONPs

Analysis of gene expression in K. pneumoniae following CuONP treatment demonstrated consistent upregulation of multiple genes related to biofilm formation and pathogenicity. All expression values were normalized to the housekeeping gene rpoB to ensure accuracy. The luxS gene, essential for quorum sensing and regulation of biofilm-associated virulence factors, was upregulated 3.87-fold, indicating CuONP-mediated modulation of quorum-sensing pathways and bacterial communication (Figure 6). The mrkA gene, encoding the structural subunit of type 3 fimbriae critical for adhesion and biofilm development, showed a 4.06-fold increase, suggesting a potential adaptive response to nanoparticle exposure and highlighting mrkA as a relevant biomarker in antibiofilm strategies.4 The fimA gene, responsible for type 1 fimbriae involved in adhesion and colonization, exhibited a 13.30-fold increase, reflecting a strong CuONP-driven effect on adherence mechanisms.7 The rcsA gene, part of the rcs phosphorelay system regulating capsule synthesis and biofilm maturation, was upregulated 24.87-fold, suggesting nanoparticle-induced capsule-associated stress responses.8 Finally, kpa, linked to fimbrial components for surface attachment and colonization, demonstrated the highest increase at 49.36-fold, underscoring the profound impact of CuONPs on adhesion pathways and bacterial persistence.3 To validate the relative expression levels derived from RT-qPCR, statistical comparisons were conducted on Cq values (target adjusted to the housekeeping gene rpoB) between the control and CuONPs-treated groups. The research revealed that all examined genes exhibited significant upregulation after exposure to CuONPs: luxS (p = 0.003), mrkA (p = 0.001), fimA (p = 0.0005), rcsA (p = 0.0006), and kpa (p < 0.0001). The results validate that the observed fold variations, varying from roughly 4-fold for luxS to over 45-fold for kpa, are not attributable to random variation but signify statistically meaningful transcriptional responses. The data collectively demonstrate that CuONPs significantly influence biofilm-related and pathogenicity pathways in K. pneumoniae. The data indicate that CuONPs significantly modify gene expression patterns related to biofilm formation, virulence, and stress adaptation in K. pneumoniae, affecting pathogenicity and antimicrobial resistance mechanisms.

Figure 6. Gene expression was quantified by RT-qPCR and expressed as relative quantity (RQ) compared to the untreated control. All tested genes (luxS, mrkA, fimA, rcsA, and kpa) showed significant upregulation, with kpa exhibiting the highest expression (49.36-fold), indicating strong activation of adhesion and biofilm-related pathways in response to CuONPs

Among the top-priority diseases designated by the World Health Organization (WHO), multidrug-resistant (MDR) K. pneumoniae has arisen as a major concern for public health around the world. Persistent infections, treatment failure, and increased morbidity and mortality are greatly exacerbated by its capacity to establish strong biofilms on both host tissues and medical devices. Traditional antibiotics have a very low success rate against biofilm-associated bacteria since these microbes are up to a thousand times more resistant to these drugs.24 The increasing resistance to existing antibiotics highlights the critical need for new approaches that can eradicate K. pneumoniae in its biofilm and in its planktonic forms. Because of their diverse antibacterial mechanisms, unique physicochemical features, and ability to disrupt biofilm formation, metal-based nanoparticles like CuONPs have garnered a lot of attention in this context.25 This research looks at the phenotypic and gene expression impacts of CuONPs in K. pneumoniae, namely their antibacterial and antibiofilm capabilities. The antibacterial efficacy of CuONPs against K. pneumoniae was shown to be significantly concentration-dependent, as evidenced by the agar diffusion experiment. The inhibition zones varied from 20 mm at the maximum concentration (200 mg/ml) to 10 mm at the minimum (3.125 mg/ml), clearly demonstrating that elevated CuONP concentration improves antibacterial effectiveness (Figure 2). The results align with Khairy et al., who documented comparable dose-dependent bactericidal efficacy, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) between 62.5 and 125 µg/ml.13 Similarly, studies highlighted the efficacy of CuONPs against biofilm-forming bacteria, accentuating their therapeutic applicability in addressing illnesses linked to biofilms and antibiotic resistance.26,27 Numerous supplementary investigations have shown inhibition zones ranging from 13 to 20 mm, hence reinforcing the efficacy and dependability of CuONPs as antimicrobial agents in medical and industrial contexts.28-30 In addition to the diffusion data, optical density (OD600) tests indicated a significant reduction in bacterial growth at elevated CuONP concentrations. Specifically, concentrations of 50 mg/ml and higher (100 mg/ml and 200 mg/ml) demonstrated almost total suppression of K. pneumoniae growth, corroborating the bactericidal activity at increased dosages. This data corresponds with previous observations, indicating that lower doses displayed bacteriostatic effects, but greater amounts resulted in complete bacterial elimination.31,32 These data together highlight the significant potential of CuONPs as effective antibacterial agents, particularly in suppressing K. pneumoniae at high concentrations, hence endorsing their prospective use in therapeutic and preventative contexts.

The synergistic effect of CuONPs with antibiotics was evaluated using the disc diffusion method, providing preliminary qualitative evidence of enhanced antibacterial activity. This method is ineffective in obtaining measurable values for interaction strength. The checkerboard assay, which assesses the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI), is considered the gold standard for synergy evaluation. Checkerboard analysis was omitted from this study owing to constraints in resources and time. We acknowledge this as a constraint and recommend that future studies incorporate checkerboard assays and time-kill synergy experiments to validate and quantify the observed interactions. This work demonstrated substantial synergistic antibacterial activity of CuONPs in conjunction with the medicines imipenem (IPM), cotrimoxazole (COT), and clindamycin (CD) against K. pneumoniae. CuONPs combined with IPM notably enhanced antibacterial efficacy, significantly reducing bacterial proliferation and resistance compared to treatments with each agent alone, as shown in Figure 3, as corroborated by recent studies by Rand6 and Valadbeigi et al.33 Similarly, combining CuONPs with cotrimoxazole markedly increased the inhibition zone to 37 mm, surpassing the effects of CuONPs (16.3 mm) or cotrimoxazole (14.7 mm) individually. This synergy likely results from nanoparticle-induced membrane disruption enhancing antibiotic penetration, aligning with findings from Javadi et al.34 Furthermore, the combination of CuONPs with clindamycin dramatically restored antibacterial activity against K. pneumoniae, producing a substantial inhibition zone (~30-31 mm) compared to negligible effects from clindamycin alone. This pronounced synergy appears driven by CuONP-mediated membrane damage, oxidative stress, and increased antibiotic uptake, thereby extending the spectrum of clindamycin to include Gram-negative pathogens, supported by previous work from Quintero-Garrido et al.35 and Alazavi.36 Collectively, these findings highlight CuONPs’ potential as robust adjunctive agents capable of overcoming bacterial resistance and enhancing antibiotic effectiveness against multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae.37,38

This study exhibited a distinct dose-dependent antibiofilm efficacy of CuONPs. against K. pneumoniae. Lower doses (1.56-6.25 mg/mL) marginally decreased biofilm production to 71.3%-89.9%, but higher concentrations (12.5-200 mg/mL) substantially reduced biofilm formation to roughly 33.8%-48.2%, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 4. The results corroborate earlier studies by Sen and Sarkar and Elbialy et al., indicating that the antibiofilm action of CuONPs is mostly attributable to structural damage and oxidative stress imposed on bacterial cells, hence augmenting antimicrobial efficacy.39,40 Studying the time-kill curve, researchers found that CuONPs effectively killed K. pneumoniae bacteria at concentrations ranging from 100-200 mg/ml, with a rapid reduction in bacterial viability observed within 6 hours. Time kill studies revealed a significant decrease in germs within the first twenty-four hours. Figure 5 shows that the killing impact peaked at 32 hours, and there was no further substantial decline in viable numbers after that. Intermediate and lower amounts had limited efficacy, underscoring dosage as a pivotal element in bacterial elimination. The findings correspond with earlier research by Rand and Shehabeldine et al., which also showed strong bactericidal effects and decreased bacterial growth using CuONPs, highlighting their potential as a viable treatment alternative for resistant bacterial infections.6,12

After treating K. pneumoniae with CuONP, gene expression analysis showed that many important genes were significantly modulated. Figure 6 shows that luxS gene expression was 3.87-fold higher than expected, which is consistent with earlier findings of quorum-sensing changes caused by nanoparticles but may have complicated effects on biofilm development.41,42 A 4.06-fold rise in the mrkA gene, which is essential for biofilm formation, is in line with previous research showing changed mrkA expression as a result of nanoparticle exposure; however, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) had the opposite impact, downregulating mrkA.42-44 There may have been consequences on bacterial adhesion and biofilm processes, since the expression of the fimA gene rose by a factor of 13.30. Nanoparticles of zinc oxide and silver have been found to decrease fimA expression and biofilm formation, respectively, in previous research.45,46 Furthermore, rcsA expression, which is critical for biofilm development and capsule production, increased significantly (24.87-fold), contradicting previous research suggesting that nanoparticles downregulate genes related to capsules and demonstrating how nanoparticle properties impact bacterial gene responses.47 The last finding is the kpa gene expression, which rose 49.36-fold. This indicates that CuONPs have a major impact on the adhesion processes of bacteria, and it may reflect adaptive bacterial responses before biofilm breakdown.9,48 The results show that nanoparticles interact with bacterial regulatory systems in complex and diverse ways, which has important consequences for antibiofilm tactics. This work utilized a singular reference strain, K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603, recognized for its characterization and reproducibility in biofilm formation, frequently exploited in antibiotic investigations. This selection guaranteed experimental consistency and comparability with prior research, although it fails to adequately represent the genetic and phenotypic diversity of clinical K. pneumoniae isolates found in healthcare environments. Consequently, the results presented herein must be regarded with prudence when generalizing to wider clinical scenarios. Future research will include several clinical isolates to confirm the relevance and translational importance of CuONPs across different pathogenic contexts.

This study demonstrates substantial antibacterial and antibiofilm properties of CuONPs against K. pneumoniae, effectively suppressing bacterial proliferation, obstructing biofilm development, and significantly enhancing antibiotic effectiveness in combination with imipenem, cotrimoxazole, and clindamycin. A novel contribution of our work is the detailed exploration and clear demonstration of the molecular-level impact of CuONPs on biofilm-associated regulatory networks, particularly through significant modulation of genes such as luxS, mrkA, fimA, rcsA, and kpa. These gene expression alterations highlight the complex adaptive bacterial responses elicited by nanoparticle exposure. Our findings strongly support the potential of CuONPs as therapeutic agents for treating multidrug-resistant and biofilm-associated infections. Future research should further investigate in vivo efficacy, biocompatibility, detailed molecular pathways, and targeted nanoparticle modifications to improve stability, effectiveness, and safety, thus fully establishing their clinical utility.

Limitations of the study

The study on CuONPs, a type of nanoparticle, has limitations due to its reliance on in vitro assays and lack of in vivo validation or cytotoxicity evaluations. The study used a single strain of K. pneumoniae, which limits generalizability. The study also did not conduct physicochemical studies like Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), zeta potential measurements, and drug release profiling, which are crucial for assessing nanoparticle stability, dispersibility, and therapeutic efficacy. This lack of these studies is a constraint and will be addressed in future research. The study also excluded agarose gel electrophoresis images of PCR products, which could improve methodological transparency and complement qPCR findings. The study’s limitations highlight the need for more comprehensive physicochemical characterization of CuONPs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Postgraduate Centre at Management and Science University (MSU) and the Department of Biotechnology, College of Science, University of Baghdad, for their support, guidance, and provision of essential facilities for conducting this research. The authors also thank MSU for their financial support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

MAA conceptualized and designed the study and supervised the laboratory work. HA, MAA and LAY performed data collection and analysis. LAY in-charge of the laboratory experiment protocols, and ensured the accuracy of the results. HA, MAA, and LAY wrote the manuscript. MAA reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

This study was funded by Management and Science University (MSU) under Grant ID SG-003-012023-SGS.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Moo C-L, Yang S-K, Yusoff K, et al. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) and Alternative Approaches to Overcome AMR. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2020;17(4):430-447.

Crossref - Vestby LK, Gronseth T, Simm R, Nesse LL. Bacterial biofilm and its role in the pathogenesis of disease. Antibiotics. 2020;9(2):59.

Crossref - Guerra MES, Destro G, Vieira B, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae Biofilms and Their Role in Disease Pathogenesis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12(5):1-13.

Crossref - Kafa AHT, Aslan R, Dastan SD, Celik C, Hasbek M, Eminoglu A. Molecular diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates: antimicrobial resistance, virulence, and biofilm formation. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2024;44(5):361-377.

Crossref - Ribeiro AI, Dias AM, Zille A. Synergistic Effects between Metal Nanoparticles and Commercial Antimicrobial Agents: A Review. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2022;5(3):3030-3064.

Crossref - Rand MA. Synergistic Effect of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles for Enhancing Antimicrobial Activity Against K. pneumoniae and S. aureus. Iraqi J Agric Sci. 2024;55(1):353-60.

Crossref - Assoni L, Ciaparin I, Trentini MM, et al. Protection Against Pneumonia Induced by Vaccination with Fimbriae Subunits from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Vaccines. 2025;13(3):303.

Crossref - Elken EM, Tan ZN, Wang Q, et al. Impact of Sub-MIC Eugenol on Klebsiella pneumoniae Biofilm Formation via Upregulation of rcsB. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:945491.

Crossref - Afrasiabi S, Partoazar A. Targeting bacterial biofilm-related genes with nanoparticle-based strategies. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1387114.

Crossref - Gudkov S V, Burmistrov DE, Fomina PA, Validov SZ, Kozlov VA. Antibacterial Properties of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles (Review). Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2024;25(21):11563.

Crossref - Ivkovic IK, Kurajica S, Domanovac MV, Muzina K, Boric I. Biocidal properties of CuO nanoparticles. Technol Acta-Scientific/professional J Chem Technol. 2024;17(1):19-24.

Crossref - Shehabeldine AM, Amin BH, Hagras FA, et al. Potential Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Properties of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles: Time-Kill Kinetic Essay and Ultrastructure of Pathogenic Bacterial Cells. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2023;195(1):467-85.

Crossref - Khairy T, Amin DH, Salama HM, et al. Antibacterial activity of green synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):1-21.

Crossref - Awaad A, Olama ZA, El-Subruiti GM, Ali SM. The dual activity of CaONPs as a cancer treatment substance and at the same time resistance to harmful microbes. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):1-13.

Crossref - Hudzicki J. Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test Protocol. Am Soc Microbiol. 2009;15(1):1-13. https://www.asm.org/Protocols/Kirby-Bauer-Disk-Diffusion-Susceptibility-Test-pro

- Chikezie IO. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) using a novel dilution tube method. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2017;11(23):977-980.

Crossref - Alnuaimi MTA, AL-Hayanni HSA, Aljanabi ZZ. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles from Sophora flavescens extract and their antibacterial effect against some pathogenic bacteria. Malays J Microbiol. 2023;19(1):74-82.

Crossref - Murugan S. Investigation of the Synergistic Antibacterial Action of Copper Nanoparticles on Certain Antibiotics Against Human Pathogens. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;10(10):83.

Crossref - Stepanovic S, Vukovic D, Dakic I, Savic B, Svabic-Vlahovic M. A modified microtiter-plate test for quantification of staphylococcal biofilm formation. J Microbiol Methods. 2000;40(2):175-179.

Crossref - Alshareef F. Protocol to Evaluate Antibacterial Activity MIC, FIC and Time Kill Method. Acta Sci Microbiol. 2021;4(5):02-6.

Crossref - Foerster S, Unemo M, Hathaway LJ, Low N, Althaus CL. Time-kill curve analysis and pharmacodynamic modelling for in vitro evaluation of antimicrobials against Neisseria gonorrhoeae. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:216.

Crossref - Flores-Rabago KM, Rivera-Mendoza D, Vilchis-Nestor AR, Juarez-Moreno K, Castro-Longoria E. Antibacterial Activity of Biosynthesized Copper Oxide Nanoparticles (CuONPs) Using Ganoderma sessile. Antibiotics. 2023;12(8):1251.

Crossref - Kosilova IS, Domotenko L V., Khramov M V. Analysis of antibiotic sensitivity of clinical strains of microorganisms with the Russian Mueller-Hinton broth. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2024;101(6):820-827.

Crossref - Algadi H, Alhoot MA, Al-Maleki AR, Purwitasari N. Effects of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles against Biofilm-Forming Bacteria: A Systematic Review. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2024;34(9):1748-1756.

Crossref - Algadi H, Alhoot MA, Yaaqoob LA. Systematic review of antibacterial potential in calcium oxide and silicon oxide nanoparticles for clinical and environmental infection control. J Appl Biomed. 2025;23(1):1-11.

Crossref - Li Y, Kumar S, Zhang L. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance and Developments in Therapeutic Strategies to Combat Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection. Infect Drug Resist. 2024;17:1107-1119.

Crossref - Ahmed AE, El-din Thabet AN, Esmat MM. Copper Oxide Nanoparticles’ Anti-biofilm Activity against MDR Gram negative bacilli. Sohag Med J. 2022;27(1.):10-17.

Crossref - Dawat DG, Zajmi A, Saud SN. Antimicrobial activity of alloy metals and phage on Elizabethkingia anophelis. Malaysian J Microsc. 2021;17(1):41-55.

- Ali NR, Hassouni MH. Characterization And Antimicrobial Activity of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesized by Crocus Sativus Extract. Int J Sci Res Sci Eng Technol. 2024;11(1):241-249.

- Muthu MS, Rejith SG, Ajith P, Agnes J, Anand DP. Antibactirial activity of Copper oxide Nano particles against gram positive and negative bacterial strain synthesized by precipitation Techniqe. Int J Zool Appl Biosci. 2022;7(1):17-22.

Crossref - Jafar NNA, Hamid JA, Altalbawy FMA, et al. Gadolinium (Gd)-based nanostructures as dual-armoured materials for microbial therapy and cancer theranostics. J Microencapsul. 2025;42(3):239-65.

Crossref - Ali SM, Ismael TK, Lateef RA, Al-Timimi MH. Antimicrobial Activity of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles on Multidrug Resistant Bacteria MDR and C albicans. Acad Sci J. 2023;1(1):39-74.

Crossref - Valadbeigi M, Mahmoudifard M, Ganji SM, Mehrabian S. Study on the antibacterial effect of CuO nanoparticles on Klebsiella pneumonia bacteria: Efficient treatment for colorectal cancer. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2023;70(6):1785-1793.

Crossref - Javadi M, Soltani H, Shokri R. Antimicrobial Effect of Silver Nanoparticles and Combination with Cotrimoxazole against Salmonella Typhi in Vitro and in Animal Model. SSU Journals. 2023;31(5):6675-6682.

Crossref - Quintero-Garrido KG, Ramirez-Montiel FB, Chavez-Castillo M, et al. Antibacterial behavior and bacterial resistance analysis of P. aeruginosa in contact with copper nanoparticles. Mex J Biotechnol. 2023;8(1):1-20.

Crossref - Alazavi F, Molavi F, Tehranipoor M. Synergistic effect of copper oxide nanoparticles and chloramphenicol antibiotic on MexA gene expression of pump efflux system in drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Med J Tabriz Univ Med Sci. 2022;44(2):127-138.

Crossref - Aidiel MRA, Maisarah AM, Khalid K, Nik Ramli NN, Tang SGH, Adam SH. Polymethoxyflavones transcends expectation, a prominent flavonoid subclass from Kaempferia parviflora: A critical review. Arab J Chem. 2024;17(1):105364.

Crossref - Bin Sahadan MY, Tong WY, Tan WN, et al. Phomopsidione nanoparticles coated contact lenses reduce microbial keratitis causing pathogens. Exp Eye Res. 2019;178:10-14.

Crossref - Sen S, Sarkar K. Effective Biocidal and Wound Healing Cogency of Biocompatible Glutathione: Citrate-Capped Copper Oxide Nanoparticles against Multidrug-Resistant Pathogenic Enterobacteria. Microb Drug Resist. 2021;27(5):616-627.

Crossref - Elbialy NA, Elhakim HKA, Mohamed MH, Zakaria Z. Evaluation of the synergistic effect of chitosan metal ions (Cu2+/Co2+) in combination with antibiotics to counteract the effects on antibiotic resistant bacteria. RSC Adv. 2023;13(26):17978-17990.

Crossref - Pourmehdiabadi A, Nobakht MS, Balajorshari BH, Yazdi MR, Amini K. Investigating the effects of zinc oxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles on the formation of biofilm and persister cells in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Basic Microbiol. 2024;64(5):2300454.

Crossref - Al-Najim AN, Hamid AT, Basheer AA, Mahmood FN, Hasan EMA. Effect of nanoparticles on the expression of virulence and biofilm genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Regul Mech Biosyst. 2024;15(4):826-829.

Crossref - Bai B, Saranya S, Dheepaasri V, et al. Biosynthesized copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) enhances the anti-biofilm efficacy against K. pneumoniae and

S. aureus. J King Saud Univ – Sci. 2022;34(6):102120.

Crossref - Mousavi SM, Mousavi SMA, Moeinizadeh M, Aghajanidelavar M, Rajabi S, Mirshekar M. Evaluation of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles effects on expression levels of virulence and biofilm related genes of multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. J Basic Microbiol. 2023;63(6):632-645.

Crossref - Shivaee A, Kashani SK, Mohammadzadeh R, Ebrahimi MT. Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle on the Expression of mrkA and fimA in Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Med Bacteriol. 2021;10(3):1-10.

- Elashkar E, Alfaraj R, El-Borady OM, Amer MM, Algammal AM, El-Demerdash AS. Novel silver nanoparticle-based biomaterials for combating Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilms. Front Microbiol. 2025;15:1507274.

Crossref - Kudaer NB, Risan MH, Yousif E, Kadhom M, Raheem R, Salman I. Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Capsular Gene Expression in Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Clinical Samples. Biomimetics. 2022;7(4):180.

Crossref - Khan AU, Hussain T, Abdullah, et al. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activity of Ficus carica-Mediated Calcium Oxide (CaONPs) Phyto-Nanoparticles. Molecules. 2023;28(14):5553.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.