ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Blood is a body fluid. When it contacts oxygen, it can clot, forming a dark solid substance. In accidents involving wounds, blood is released and can stain clothing when absorbed by fabrics. Removing blood stains from fabrics is challenging with various commercial detergents. This study aimed to determine the efficacy of commercially available detergent powder supplemented with amylase and protease enzymes in removing bloodstains from textiles. Stutzerimonas xanthomarina and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes were isolated from soil and examined for their enzymatic activity. The results demonstrated that these enzymes can effectively remove bloodstains from cotton fabric, with maximum activity observed at 50% saturation with ammonium sulfate and specific activity of protease at 93.45 ± 2.17 U/mg and amylase at 36.28 ± 1.36 U/mg. This study suggests that the addition of enzymes to chemical detergents can enhance their surface impact and improve their effectiveness. These findings indicate a potential for the development of more efficient detergents.

Blood Stain, Protease, Amylase, Crude Enzyme, Detergent Powder

Clothing is a basic human need, with cotton being the most widely used fabric worldwide. Stains on fabrics result from physical or chemical interactions and are classified as surface, chemical, or biological stains. Blood stains, common in hospitals and homes, can be fresh or aged.1 Fresh stains are water-soluble due to ferrous ions, making them easier to remove. Aged stains are harder to clean, as ferric ions form insoluble protein complexes.2 Traditionally, physical and chemical methods were used for the removal of stains from fabrics. Detergents remove stains from cloth by breaking down the complex particles present on the stain into small particles.3 Use of harsh chemicals for stain removal hurts the fabrics, human health, and also the environment. Exposure to detergent chemicals on the skin may result in skin irritation and allergy in humans.4 Detergents contain surfactants, bleaching agents, and builders. The draining of the chemicals to the environment may lead to conditions such as altered soil and water quality.5 Eutrophication of rivers and lakes due to excess phosphate is a negative impact of synthetic surfactants in the detergent.6 Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA), one of the commonly used builders, is not readily biodegradable and can remobilize heavy metals, resulting in contamination of soil and water.

Enzymes are catalysts widely used for industrial purposes because they are biodegradable, have low toxic effects, and are close to favorable environmental conditions.7,8 Microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, produce enzymes such as protease, amylase, cellulase, lipase, etc., and are safe for a sustainable environment.9

Microbial enzyme applications are used in a wide range of industries, including food and beverage industries, healthcare, detergents, animal feeds, and the production of biofuels10 for better yield. Applications of enzymes in the detergent industry are significant. Enzymes produced by microbes can break down complex particles or components into smaller units, and these simple particles can be easily removed compared to larger and more complex units from fibers.11 Enzymes are considered a green chemical for stain removal.12 When compared with the chemical detergents, enzyme-based detergent formulations have better destaining ability as well as maintaining the brightness and quality of the fabrics after the washing process.13,14 Amylase and protease play an important role in detergent formulation. Protease enzymes are capable of hydrolyzing peptide bonds of the stain from fabric.15 Amylase enzymes catalyze the breakdown of complex compounds, such as glycogen or starch, to oligosaccharides.16 The use of protease enzymes for the detergent industry began in 1913; until 1963, their application was not revealed.17 In the 1960s, protease enzymes were used for the removal of protein-based stains and amylase enzymes for starch-based stains. Previous studies have revealed that stains caused by proteins or starch are efficiently removed from clothes using detergents supplemented with enzymes rather than non-enzyme detergents.18

Enzymatic detergents are well-documented, the majority of studies concentrate on single-enzyme systems.19 This study introduces a dual-enzyme system wherein protease targets the proteinaceous component of blood, primarily hemoglobin, and amylase degrades polysaccharide matrices often associated with complex stains. This complementary mechanism enhances cleaning efficiency beyond the capabilities of single enzymes.20 P. pseudoalcaligenes is recognized for producing alkaline proteases with high stability under detergent-compatible conditions,21 whereas S. xanthomarina, though less explored, has demonstrated potential in amylase production with industrial applicability.22 Their combined use is novel, as no prior study has reported their enzymatic compatibility or performance in textile stain removal. The employment of such non-pathogenic, robust strains also ensures environmental safety and biodegradability, aligning with sustainable cleaning technologies.12

Currently, the design and application of detergent compositions are centred on creating a product that is sensitive to environmental conditions.23 The present study aims to analyze the effect of an enzyme cocktail for the removal of blood stains from cotton fabrics.

Collection and isolation of the sample

Soil samples from the Madiwala vegetable market, Bengaluru, were collected in sterile bottles and transported to the laboratory. One gram of the sample was resuspended in 10 ml of sterile distilled water and serially diluted to 108. From each dilution, 0.1 ml was spread on the nutrient agar media and incubated at 37 °C for 24 to 72 hours. After incubation, individual colonies were selected based on different colony morphology and subcultured to fresh nutrient agar plates. Colony morphology, such as margin, elevation, color, and texture analyzed, and cell morphology and Gram reaction were studied.24 Biochemical tests such as indole, methyl red, Voges-Proskauer test, citrate utilization test, oxidase test, catalase test, and triple sugar iron agar test were performed by standard protocol.25 Selected isolates were stored in glycerol stock for further use.

Screening of microorganisms

Protease activity of selected isolates was studied by patching the colonies on skimmed milk agar (dextrose (1 g/L), yeast extract (2.5 g/L), skimmed milk (2.8%), and agar (2%)) and incubated at 37 °C. The appearance of a clear zone around the colony indicated the protease production by isolate.26

To check the amylase activity, selected bacterial colonies were patched on starch agar (peptone (5 g/L), yeast extract (3 g/L), starch (2 g/L), agar (2%)) and incubated at 37 °C. Once the colonies had grown, the plate was flooded with iodine solution, and the appearance of a clear zone around the colony showed the production of amylase by the organism.27

The colonies that showed the highest diameter of clear zone on plates for amylase and protease enzymes were further characterised using 16S rRNA sequencing.

Identification of bacteria

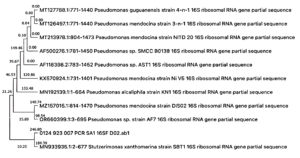

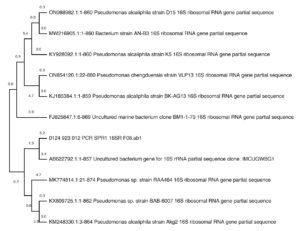

Molecular characterization of the selected bacterial isolates was carried out at Barcode Biosciences [Bengaluru, Karnataka]. Using the 16S rRNA sequence, BLAST analysis was done against the ‘nr’ database of the NCBI GenBank database. Based on the maximum identity score, ten sequences were selected and aligned using the multiple alignment software program CLUSTAL OMEGA, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA IX software.28

Crude enzyme from bacteria

For enzyme production, selected bacterial isolates were inoculated into 50 mL of nutrient broth containing either 0.5% starch (for amylase) or skimmed milk (for protease) and incubated at 37 °C for 48 hours.29 Following incubation, the cultures were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C to obtain the cell-free supernatant, which served as the crude enzyme extract. To partially purify the enzymes, fractional ammonium sulfate precipitation was performed with a 10% gradient ranging from 10% to 70% saturation, aiming to selectively precipitate protein fractions enriched in enzymes while removing unwanted soluble proteins.30 After reaching each saturation level, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The enzyme pellets obtained were then resuspended in 10 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for further characterization.31

Enzyme assay

Amylase activity was determined by mixing 1.0 mL of crude extract with 1 mL of 1% starch (in pH 7.0 phosphate buffer) and incubating the mixture at 37 °C for 30 minutes. The amount of reducing sugar released was measured using the DNS method,32 with D-glucose serving as the standard for the curve (absorbance measured at 600 nm).

Protease activity was evaluated by incubating 1.0 mL of crude extract with 1.0 mL of 0.65% casein (in pH 7.0 phosphate buffer) at 37 °C for 30 minutes. The peptide fragments released were quantified using the Folin-Ciocalteu (F-C) method,33 with L-tyrosine as the standard (absorbance at 660 nm).

Determination of optimum temperature of the partially purified enzyme

To assess the temperature stability of the partially purified enzymes, the standard assay mixtures (as described above) were incubated at various temperatures ranging from 20 °C to 70 °C in 10 °C increments for 30 minutes. Enzyme activity was then assessed using the DNS method (for amylase) and F-C method (for protease) to identify the optimal temperatures for enzymatic activity.

Application of crude enzyme in laundry detergent

The practical application of the crude enzyme extracts was tested through blood stain removal experiments on white cotton fabric. One-inch square cotton pieces were stained with fresh chicken blood and incubated at 60 °C for 1 hour to set the stain. The stained fabric samples were then treated with crude amylase and protease preparations, both separately and in combination, with and without the addition of commercial laundry detergent (Table 1). The experimental procedures for stain removal involving biological materials were conducted in compliance with institutional biosafety guidelines. All handling and disposal of materials containing blood were performed following Biosafety Level 2 (BSL-2) laboratory safety protocols.

Table (1):

Experimental setup for blood stain removal from cloth

Experiment setup |

Distilled water (ml) |

Chemical detergent powder |

Amylase enzyme (ml) |

Protease enzyme (ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Control |

50 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Beaker 1 |

50 |

5 mg/ml |

0 |

0 |

Beaker 2 |

47 |

– |

3 |

0 |

Beaker 3 |

47 |

5 mg/ml |

3 |

0 |

Beaker 4 |

47 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

Beaker 5 |

47 |

5 mg/ml |

0 |

3 |

Beaker 6 |

44 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

Beaker 7 |

44 |

5 mg/ml |

3 |

3 |

Spectrophotometric determination of stain removal efficiency

To evaluate the efficacy of partially purified enzymes in stain removal, a spectrophotometric method was utilized, focusing on changes in absorbance at 420 nm. Fabric samples, each measuring 1 inch² and stained with chicken blood, underwent various treatments, followed by incubation at 40 °C for 60 minutes, and subsequent rinsing with distilled water. Post-treatment, the fabrics were immersed in 5 mL of water. The absorbance of the resultant solution was then measured at 420 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer.34

Isolation and screening of Amylase and Protease-producing bacteria

Ten soil samples were collected from Madiwala market, Bengaluru, and inoculated on nutrient agar plates by the spread plate method.35 Colonies with different morphologies were screened for amylase production and protease production. Amylase production was confirmed by iodine, and protease production was confirmed on the skimmed milk agar plate. Based on the highest diameter of the clear zone on the plate, isolates were labeled LMSA and LMSPR for bacterial isolates. Most favourable isolates LMSA, LMSPR (Figure 1a and 1b), which had amylase and protease activity, were biochemically characterised (Table 2). In colony morphology, LMSA had a dry texture, milky white colour, round shape with filamentous margin and umbonate elevation, and LMSPR appeared as a dry, creamy coloured, filamentous colony with irregular shape, and it showed umbonate elevation. Microscopic study of LMSA and LMSPR was analysed by the Gram staining method, and both bacterial colonies were observed to be Gram-negative rods.

Table (2):

Biochemical characterisation of amylase and protease producing isolates

| No. | Sample name | Indole | MR | VP | Citrate | Oxidase | Catalase | TSI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FERM | GAS | ||||||||

| 1 | LMSA | – | + | – | + | Pos | +++ | K/A | + |

| 2 | LMSPR | – | + | – | +++ | Pos | ++ | K/A | + |

Figure 1. Isolation of amylase-producing and protease-producing bacteria. (a) Isolate that produces amylase enzyme; starch agar plate flooded with iodine solution. (b) Isolate that produces protease enzyme on skimmed milk agar after incubation period

Bacterial identification

Molecular characterisation of LMSA and LMSPR was done by 16S rRNA sequencing method on BLAST analysis. The isolate identified as LMSA was Stutzerimonas xanthomarina (Figure 2) that showed 98% sequence similarity and the LMSPR as Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes (Figure 3) that showed 99.6% sequence similarity.

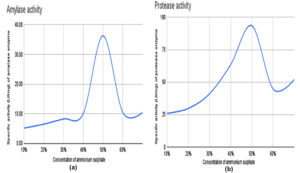

Partial purification

Partial purification of amylase and protease enzymes was performed with different concentrations of ammonium sulfate precipitation from 10% to 70% and the protein pellet from each saturation was collected and resuspended in PBS. Analysis of these collected fractions with the DNS method for amylase activity and the F-C method for protease activity showed maximum enzyme activity in the 50% ammonium sulphate saturation (Figure 4 and Table 3).

Table (3):

Partial purification for isolated protease and amylase enzymes

| Enzyme | Bacterial isolate | Purification steps | Total protein (mg/ml) | Specific activity (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease | Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes spp. | Crude extract | 0.13 | 52.2 ± 3.75 |

| 50% | 0.24 | 93.45 ± 2.17 | ||

| 70% | 0.13 | 52.2 ± 2.10 | ||

| Amylase | Stutzerimonas xanthomarina spp. | Crude extract | 0.32 | 8.74 ± 0.68 |

| 50% | 1.32 | 36.28 ± 1.36 | ||

| 70% | 0.38 | 10.51 ± 0.51 |

Figure 4. Partially purified (a) amylase from Stuzerimonas xanthomarina and (b) protease enzyme from Pseudomonas psedoalcaligenes

Effect of temperature on enzymatic activity

The influence of temperature on amylase and protease enzyme activity was carried out in different temperature ranges from 20-70 °C. Analysis of amylase activity using the DNS method revealed that 37 °C is the optimal temperature with a maximum specific activity of 36.28 U/mg.

Application of crude enzyme in laundry detergents

Blood stain removal from cotton fabrics was tested in various combinations for 20 minutes. The results of the stain removal treatment are shown in Figure 5. Blood spots washed with water do not result in any changes to the discoloration state shown in Figure 5a. Partial stain removal was observed on soiled fabrics treated with detergent (Figure 5b). Amylase enzymes effectively removed starch components from bloodstains (Figure 5c) and Figure 5d shows the removal of blood stain removal in the enzyme detergent solution formulated with amylase. Figure 5e shows protein components from bloodstains that are targeted by protease enzymes. Figures 5f and 5g show the effective disappearance of blood stains in the enzyme detergent solution formulated with amylase and protease enzymes, respectively. The effect of a combination of enzymes added to a chemical cleaning agent on the removal of blood stains from textiles results in their gradual disappearance (Figure 5h).

Figure 5. Visual observation of blood stained cotton cloth pieces treated with (a) water (50 ml), (b) commercial detergent (5 mg/ml), (c) amylase enzyme (3 ml), (d) mixture of amylase (3 ml) incorporated with commercial detergent (5 mg/ml), (e) protease enzyme (3 ml), (f) mixture of protease (3 ml) incorporated with commercial detergent (5 mg/ml), (g) mixture of amylase enzyme (3 ml) and protease enzyme (3 ml), (h) mixture of crude enzymes (6 ml) incorporated with commercial detergent (5 mg/ml)

Stain removal efficiency by the spectrophotometric method

The efficacy of stain removal by partially purified enzyme preparations was quantitatively assessed by measuring the absorbance of hemoglobin extract at 420 nm post-treatment. The control group, which involved fabric treated solely with detergent, exhibited a high absorbance value, indicating minimal stain removal. In contrast, samples treated with enzyme preparations demonstrated significantly reduced absorbance, indicative of enhanced stain clearance (Table 4). Among the treatments, the combination of amylase and protease with detergent achieved the highest stain removal percentage of 90%, followed by partially purified enzymes 86%, and finally, the detergent-only treatment with 55% stain removal efficiency. These findings suggest the potential application of these enzymes in eco-friendly laundry formulations.

Table (4):

Stain removal efficiency of protease and amylase enzymes measured by absorbance reduction at 420 nm and percentage of stain reduction

Combinations |

Absorbance (420 nm) |

% stain removal |

|---|---|---|

Control (wash with water) |

2.039 |

– |

Treated with detergent |

0.922 |

55 |

Treated with Protease |

0.616 |

70 |

Treated with Protease and detergent |

0.543 |

73 |

Treated with Amylase |

0.64 |

69 |

Treated with Amylase and detergent |

0.669 |

67 |

Treated with Amylase and Protease |

0.283 |

86 |

Treated with Amylase, Protease and detergent |

0.202 |

90 |

The microbial composition of soil originating from organic waste disposal facilities is notably enriched with organisms capable of producing hydrolytic enzymes, a characteristic widely attributed to the nutrient-rich and variable physicochemical conditions prevalent in such environments. Afrin et al. and Gupta et al. underscored the critical role these environmental factors play in facilitating the synthesis of enzymes such as amylases and proteases.35,36

In the present study, Stutzerimonas xanthomarina and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes were selectively isolated due to their significant amylase and protease enzymatic activity, respectively. The enzymatic profile of S. xanthomarina remains underexplored in current literature, particularly concerning its amylolytic capabilities. This study, therefore, contributes valuable new insights into its potential industrial applications. Conversely, P. pseudoalcaligenes has been previously associated with protease production. Palsaniya et al. reported its isolation from homemade cheese and demonstrated its spoilage potential along with proteolytic activity, indicating its relevance in both food spoilage and enzyme production domains.37

Our results align with previous reports concerning the purification and quantification of enzyme activity. Neiditch et al. observed optimal amylase activity at 60% ammonium sulfate saturation, yielding 23.95 U/mg from Bacillus spp. and 19.0 U/mg from Pseudomonas spp., consistent with our findings.34 Similarly, Shaikh et al. reported the highest protease activity at 60% ammonium sulfate saturation, suggesting that this saturation level may be broadly effective for partial purification of hydrolytic enzymes from soil microorganisms.38

Temperature was found to be a significant factor influencing enzyme activity. The optimal temperature for amylase production was observed at 30 °C, corroborating earlier studies that identified maximum specific activity at this temperature. For protease enzymes, the F-C (Folin-Ciocalteu) method confirmed maximal activity (98.325 U/mg) at 30 °C, which is consistent with the observations of Ahmed et al., who reported optimal protease function between 30-40 °C.39

Furthermore, application trials demonstrated that enzymatic treatments were superior to conventional methods for removing stains from textile fabrics. While the enzymatic activities demonstrated in laboratory environments appear promising, they lack substantial industrial applicability without further evaluation of critical application parameters. In the detergent industry, enzymes are required to function effectively under challenging conditions, such as alkaline pH levels (9-11) and in the presence of surfactants, oxidizing agents, and chelators. Consequently, merely demonstrating stain removal under optimal laboratory conditions is insufficient unless the enzyme’s stability at high pH and resistance to detergent additives are also confirmed. While water alone was ineffective and detergents only partially removed stains, enzyme-based treatments-particularly when combined with detergents-improved cleaning efficiency significantly. These findings agree with those of Saini et al. and Priyadarshini et al., who reported enhanced stain removal when protease and amylase enzymes were used in synergy with chemical detergents.40,41 In this study, the effect of enzymes in the laundry industry was demonstrated by removing blood stains from cloth commercial detergent supplemented with a combination of protease and amylase enzymes. The mutual benefits of microbial protease and amylase, derived from Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes and Stutzerimonas xanthomarina, respectively, facilitates the eco-friendly and efficient removal of blood stains from textiles. The gradual disappearance of blood stains from fabrics after treatment with an enzyme mixture highlights the promising future in developing environmentally friendly cleaning solutions. Overall, the current study contributes novel insights into the industrial potential of S. xanthomarina and P. pseudoalcaligenes, especially in textile and detergent applications.

This study elucidates the potential of Stutzerimonas xanthomarina and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes, isolated from waste soil, as sources of amylase and protease enzymes. The maximum yield of enzyme was at 60% ammonium sulfate saturation precipitation and maximum activity was at 30 °C. Enzyme-based treatments significantly enhanced the removal of blood stains from textiles, particularly when used in conjunction with detergents, underscoring their potential for eco-friendly applications in the detergent industry. Overall, the current study contributes novel insights into the industrial potential of

S. xanthomarina and P. pseudoalcaligenes, especially in textile and detergent applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Christ University, Bengaluru, for providing infrastructure facilities to carry out the work and for the financial support through the Institute Fellowship for LMA.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Padole HA. The effect of laundry detergents on stain removal from cotton fabric. Int J Res Biosci Agric Technol. 2023;10(1):1.

Crossref - Godfrey T, Reichelt J, eds. Industrial Enzymology: The Application of Enzymes in Industry. CiNii Books; 1983.

- Jangra N, Pal H, Pal S. A and Commercial Stain Removers on Textiles. Int J Eng Res Technol. 2023;12(08):643.

- Tanzer J, Meng D, Ohsaki A, et al. Laundry detergent promotes allergic skin inflammation and esophageal eosinophilia in mice. PLoS One. 2022;17(6):e0268651.

Crossref - Chirani MR, Kowsari E, Teymourian T, Ramakrishna S. Environmental Impact of Increased Soap Consumption During COVID-19 Pandemic: Biodegradable Soap Production and Sustainable Packaging. Sci Total Environ. 2021;796:149013.

Crossref - Art, Henry Warren. The Dictionary of Ecology and Environmental Science. Choice Reviews Online. 1993;31:31-1850.

Crossref - Singh A, Sharma A, Bansal S, Sharma P. Comparative Interaction Study of Amylase and Surfactants for Potential Detergent Formulation. J Mol Liq. 2018;261:397-401.

Crossref - Kumar D, Bhardwaj R, Jassal S, Goyal T, Khullar A, Gupta N. Application of enzymes for an eco-friendly approach to textile processing. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;30(28):71838-71848.

Crossref - Naganthran A, Masomian M, Rahman RNZRA, Ali MSM, Nooh HM. Improving the efficiency of new automatic dishwashing detergent formulation by addition of thermostable lipase, protease and amylase. Molecules. 2017;22(9):1577.

Crossref - Birnur A, Yenidunya AF, Akkaya R. Production and immobilization of a novel thermoalkalophilic extracellular amylase from bacilli isolate. Int J Biol Macromol. 2012;50(4):991-95.

Crossref - Adrio JL, Arnold LD. Microbial Enzymes: Tools for Biotechnological Processes. Biomolecules. 2014;4(1):117-139.

Crossref - Rai SK, Mukherjee AK. Statistical optimization of production, purification and industrial application of a laundry detergent and organic solvent-stable subtilisin-like serine protease [Alzwiprase] from Bacillus subtilis DM-04. Biochem Eng J. 2009;48(2):173-180.

Crossref - Hasan F, Shah AA, Javed S, Hameed A. Enzymes Used in Detergents: Lipases. Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;9(31):4836-4844.

Crossref - Niyonzima FN, More SS. Coproduction of Detergent Compatible Bacterial Enzymes and Stain Removal Evaluation. J Basic Microbiol. 2015;55(10):1149-1158.

Crossref - de Carvalho RV, Correa TLR, da Silva JCM, de Oliveira Mansur LRC, Martinsl MLL. Properties of an Amylase From Thermophilic Bacillus SP. Braz J Microbiol. 2008;39(1):102-107.

Crossref - Anbu P, Gopinath SCB, Chaulagain BP, Tang TH, Citartan M. Microbial Enzymes and Their Applications in Industries and Medicine 2014. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:1-3.

Crossref - Song P, Zhang X, Wang S, et al. Microbial Proteases and Their Applications. Front Microbiol. 2023;14.

Crossref - Gupta R, Gigras P, Mohapatra H, Goswami VK, Chauhan B. Microbial a-amylases: A Biotechnological Perspective. Process Biochem. 2003;38(11):1599-616.

Crossref - Mrudula S. A review on microbial alkaline proteases: Optimization of submerged fermentative production, properties, and industrial applications. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2024;60(3):383-401.

Crossref - Gupta R, Beg Q, Lorenz P. Bacterial alkaline proteases: molecular approaches and industrial applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;59(1):15-32.

Crossref - Beg QK, Gupta R. Purification and characterization of an oxidation-stable, thiol-dependent serine alkaline protease from Bacillus mojavensis. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2003;32(2):294-304.

Crossref - Sherpa MT, Das S, Najar IN, Thakur N. Draft genome sequence of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strain P13 gives insight into its protease production and assessment of sulfur and nitrogen metabolism. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2021;2(100012):100012.

Crossref - Kembhavi AA, Kulkarni A, Pant A. Salt-tolerant and Thermostable Alkaline Protease from Bacillus Subtilis NCIM No. 64. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1993;38(1-2):83-92.

Crossref - Kimura M. A Simple Method for Estimating Evolutionary Rates of Base Substitutions Through Comparative Studies of Nucleotide Sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16(2):111-20.

Crossref - Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB, Lewis BA. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74(10):3583-3597.

Crossref - Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547-49.

Crossref - Fogarty WM, Kelly CT. Microbial Enzymes and Biotechnology. Springer Science and Business Media. 2012.

- Debnath R, Mistry P, Roy P, Roy B, Saha T. Partial Purification and Characterization of a Thermophilic and Alkali-stable Laccase of Phoma Herbarum Isolate KU4 With Dye-decolorization Efficiency. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2021;51(9):901-918.

Crossref - Majeed T, Lee CC, Orts WJ, et al. Characterization of a Thermostable Protease From Bacillus Subtilis BSP Strain. BMC Biotechnol. 2024;24(1):49.

Crossref - Dahiya P, Rathi B. Characterization and application of alkaline a-amylase from Bacillus licheniformis MTCC1483 as a detergent additive. 2015;22(3):1293-1297.

- Cupp-Enyard C. Sigma’s Non-specific Protease Activity Assay – Casein as a Substrate. J Vis Exp. 2008;19:899.

Crossref - Englyst HN, Hudson GJ. Colorimetric Method for Routine Measurement of Dietary Fibre as Non-starch Polysaccharides. A Comparison With Gas-liquid Chromatography. Food Chem. 1987;24(1):63-76.

Crossref - Klinfoong R, Thummakasorn C, Ungwiwatkul S, Boontanom P, Chantarasiri A. Diversity and Activity of Amylase-producing Bacteria Isolated From Mangrove Soil in Thailand. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity. 2022;23(10).

Crossref - Neiditch OW, Mills KL, Gladstone G. The stain removal index (SRI): A new reflectometer method for measuring and reporting stain removal effectiveness. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1980;57(12):426-429.

Crossref - Afrin S, Tamanna T, Shahajadi UF, et al. Characterization of Protease-producing Bacteria From Garden Soil and Antagonistic Activity Against Pathogenic Bacteria. The Microbe. 2024;4:100123.

Crossref - Gupta N, Beliya E, Paul JS, et al. Molecular strategies to enhance stability and catalysis of extremophile-derived α-amylase using computational biology. Extremophiles. 2021;25(3):221-233.

Crossref - Palsaniya P, Sharma N, Patel S, et al. Optimization of alkaline protease production from bacteria isolated from soil. J Microbiol Biotechnol Res. 2017;2(6):858-865. Available from: https://scholarsresearchlibrary.com/JMB-vol2-iss6/JMB-2012-2-6-858-865.pdf

- Shaikh IA, Turakani B, Malpani J, et al. Extracellular Protease Production, Optimization, and Partial Purification From Bacillus Nakamurai PL4 and Its Applications. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2022;35(1):102429.

Crossref - Ahmed M, Rehman R, Siddique A, Hasan F, Ali N. Production, purification and characterization of detergent-stable, halotolerant alkaline protease for ecofriendly application in detergents’ industry. Int J Biosci. 2016;8(2):47-65.

Crossref - Saini R, Saini HS, Dahiya A. Amylases: Characteristics and Industrial Applications. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 2017;6(4):1865-1871.

- Priyadarshini S, Ray P. Exploration of Detergent-stable Alkaline a-amylase AA7 From Bacillus Sp Strain SP-CH7 Isolated From Chilika Lake. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;140:825-832.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.