ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

The aim of this investigation was to monitor the occurrence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) E. coli strains along the Upper Litany River Basin (ULRB), genotype ESBL producers, and determine their sensitivity to different essential oils (EOs). Thirty five E. coli strains were isolated and recognized using double-disc synergy test, then studied for the detection of key ESBL genes and Shiga-toxin genes using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) broth microdilution, beside the time-kill assay were applied to determine the antibacterial activity of the EOs against the ESBL E. coli. EOs activity on biofilms was detected by antibiofilm screening. 22.8% strains were verified as ESBL producers and blaCTX-M was identified in all strains, then blaTEM with 50% of prevalence, and there was no detection of blaOXA, blaSHV, and both stx1 and stx2 genes. Sesame oil revealed the highest antibacterial activity. Followed by Coconut, Lettuce, and Almond oils with a concentration ranging between 6.25% and 50%. Almond, Sesame, and Lettuce oils showed an interesting effect against biofilm formation, and Coconut and Sesame oils were effective against preformed biofilms. Our study showed the antibacterial and antibiofilm effects of EOs against ESBL E. coli.

Extended-spectrum Beta-lactamase Genes, Shiga-toxin Genes, Waterborne Pathogens, Environmental Isolates, Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, Minimum Bactericidal Concentration, Time-kill Assay, Essential Oils

The appearance of resistant bacteria represents a giant common health trouble over the world and represent a menace to the success of frequent infection treatment within a community. Antimicrobial resistance is considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be one of the extremely serious common wellness troubles. The spreading of antibiotic-resistant (ABR) bacteria is highly correlated to water pollution which can lead to life disturbing and difficulties in infections treatment.1 Numerous factors can favor the dispersal of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) within the aquatic ecosystems, beside its emergence to different localities. This consists of the vocational human susceptibility to these bacteria, the discharge of wastewater to the environment without treatment through rivers, the excessive usage of chemicals, nutrient-rich soil or water, or by the runoff from agricultural fields exposed to fertilizers.2

A deterioration of the quality for the groundwater in Lebanon is determined due to anthropogenic pollution and huge abstraction. Furthermore, the karstic nature of the surface water reservoirs leads to the increase in the chance of bacterial pollution. The ministry of environment in Lebanon (MoE, 2020) showed in SOER (State of the Environment and Future Outlook Report) presented in 2020 cooperating with United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) that the principal cause of reduced extend of wastewater treatment is the lack of connection between the previous sewage systems and the working treatment plants. According to the National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS, 2010), Lebanon generated around 310 million Cubic Meters (MCM) of wastewater. From the total produced wastewater, approximately 8% only was treated, as well as about 60% of the population was associated to a network of sewage collection (MoE, 2020), with the discharge of untreated wastewater into rivers from these networks. The previously mentioned pollution powerfully proposes the contamination of different water surfaces. It represents a water body full of evacuated or disposed antibiotics used for different medical or agricultural purposes3 and distributes pollutants such as ABR pathogens to different basic resources like the food chain.

Among these ABR bacteria, Escherichia coli (E. coli) which represents one of the most popular bacterium to show multidrug-resistance caused by the wide variety and fast emerging group of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) isolates described to be a severe challenge facing opposite the therapy of infections deriving from these ABR in health care and society settings.4 Furthermore, the resistance to cephalosporins (third- and fourth-generation antibiotics) intervened by the ESBL with other antibiotic classes like sulfonamides, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones. This have conducted to the large usage of carbapenems, which in succession is related to resistance extension to these antibiotic classes.4 ESBL phenotype is stated by enzyme families that are primarily classified into class A (CTX-M TEM, SHV, VEB, and GES families) beside class D beta-lactamases (OXA family).5 However, CTX-M type ESBL derived from mobilization of blagenes in Kluyvera spp. a non-dangerous bacterial strain.6 Nowadays, the explosive spreading for CTX-M-15 among Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumonia) as well as E. coli has enhanced the worldwide epidemiology for ESBLs CTX-M type enzymes. Nevertheless, it has been reported among numerous patient groups within various regions in the globe a regional modification concerning the occurrence, sequence types (STs), and circulating enzyme types among ESBL producers.7 In Asia and South Africa, the incidence of ESBL producers is greater than 20%.8 Moreover, the finding of the pattern for ABR with the principal genes within ESBL E. coli can give useful information concerning their epidemiology and the creation of new antimicrobial therapy.9

Other group of E. coli that represents a major root of food-borne and water-borne diseases is Shiga toxin E. coli (STEC). The infection by this kind of bacteria could be mortal. It might lead to grave disorders like hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) and hemorrhagic colitis.10 Two major kinds of Shiga toxin are produced by STEC and named as Shiga toxin 1 (Stx1) and Shiga toxin 2 (encoding for ESBL enzymes;2).11 Currently, it has been reported that the growth and survival of a subset of STEC, E. coli O157: H7, is found within various aquatic ecosystems.12,13 Drinking water and food contamination with STEC constitute a critical health concern by reason of the huge danger of diarrheal diseases water-borne outbreaks.14 Moreover, the lack of treatment to surface waters used as drinking water reservoir, failure of sewage assemblage processes, as well as incomplete water disposal have been the cause of potable water contamination via STEC.15 A previous study16 has revealed the detection of ESBL-producing STEC isolates which represents a worth health problem, since this kind of E. coli shows a high antimicrobial resistance, in addition to the production of Shiga toxin. The antibiotics usage in different regions surrounding the Litany River and the rise in the frequency of multidrug-resistant ESBL in Lebanon can lead to a change in the incidence of ESBL genotypes, and can increase the prevalence of diarrheal diseases caused by STEC.

On the other hand, the identification and the description at the genetic level for ESBL E. coli could be helpful for the improvement of suitable treatment strategies and precaution from the disease. To our knowledge, no data was previously published addressing the prevalence of ESBL among the ULRB. The spread of ESBL-producing E. coli in Litany River water presents a remarkable public health trouble due to the proliferation of waterborne diseases and antibiotic resistance and highlights the broader issue of antibiotic resistance in the environment which has forced researchers to work on new antimicrobial drugs in order to act toward different human pathogens17 and explore the use of plant-based essential oils as an effective antimicrobial approach to combat these resistant bacteria.

Essential oils (EOs) chemical composition beside their antimicrobial effect were analyzed by numerous investigators.18 The phyto-components in different EOs have been described to show a vast extent of their biological activities involving antibacterial,19 antiviral,20 and antifungal21 effects. EOs effectivity is influenced by the pathogens type and the extraction methods.22

The purpose of this investigation was to assess the rate of fecal ESBL E. coli isolated from different sampling sites of the ULRB, as well as STEC ESBL E. coli by detection of various virulent genes; including blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaOXA, encoding for ESBL enzymes; and stx1 and stx2, encoding for Shiga toxin. Moreover, it suggests the utilization of EOs as antibacterial agents to cure the infections caused by the pathogenic bacteria present in Rivers of Lebanon.

Water samples collection and bacterial isolation

In this investigation, accomplished from March 2019 to February 2020, seventy-two (n = 72) freshwater samples were taken from 6 selected sampling sites along the ULRB and were sent to the Microbiology Department of LARI – Tal Amara – Beqaa, Lebanon. Membrane filtration method was applied to isolate the E. coli according to ISO 9308-1:2000.23 Filters were passed onto RAPID’ E. coli 2 agar (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) plates then incubated during 18-24 h at 44 °C. Different E. coli strains were recognized using the analytical profile index (API) 20E gallery (BioMerieux – France) based on the procedure supported by the producer. E. coli ATCC 25922 has been considered to be control for biochemical description of different E. coli isolates.

Antibiotic resistance profiles

The antibiotic resistance of isolated strains was evaluated using Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion test utilizing Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standards (CLSI, 2019). 20 different antibiotics were used from different classes including Combinations of Beta-lactamase inhibitors: Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (AUG; 30 µg); Cephalosporins: Cephalexin (CL; 30 µg), Cefuroxime (CXM; 30 µg), Ceftazidime (CAZ; 30 µg), Cefotaxime (CTX; 5 µg), and Cefepime (FEP; 30 µg); Penicillin: Amoxicillin (AM; 10 µg) and Piperacillin + Tazobactam (TPZ; 36 µg); Carbapenems: Ertapenem (ETP: 10 µg) and Imipenem (IPM; 10 µg); Aminoglycosides: Gentamycin (GMN; 10 µg), Amikacin (AKN; 30 µg), and Tobramycin (TOB; 10 µg); Quinolones: Nalidixic acid (NA; 30 µg); Fluoroquinolones: Levofloxacin (LVX 5 µg) and Ciprofloxacin (CIP; 5 µg); Monobactams: Aztreonam (ATM 30 µg); Sulfonamides: Sulfamethoxazole (TS; 25 µg); Tetracycline: Tetracycline (TE; 30 µg); and others: Colistin (CT; 10 µg). Then, the plates were incubated aerobically at 37 °C during 24 h. Besides, diameters of inhibition zones were detected in harmony with guidelines of CLSI.25 Finally, the strains were classified into susceptible, intermediate, or resistant. Intermediate strains were considered to be resistant.

Phenotypic detection of ESBL E. coli

Strains recognized as E. coli were evaluated for the ability of ESBL production using double-disk synergy test (DDST) in which disks of Cefotaxime (5 µg), cefepime (30 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), and aztreonam (30 µg) were positioned above MHA plates with a space of about 30 mm far-off amoxicillin clavulanic acid (AMC; 30 µg) disk placed in the center. A lawn culture for the organisms was created on the MHA plate, as proposed by CLSI.26 ESBL strains were detected when synergism was shown by any of the four mentioned antibiotics toward the AMC disk in the center, leading to the formation of a representative ‘keyhole-shaped’ or ‘ellipsis-shaped’ area. The identified ESBL strains were later assessed to detect ESBL genes as well as Shiga toxin genes using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and definite primers.

DNA isolation and genotyping of ESBL positive strains

Eight ESBL E. coli isolates were assessed for 4 ESBL genes: blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaOXA, and blaSHV and Shiga toxin genes (stx1 and stx2). Heat lysis method was used to isolate the bacterial DNA.27 Each strain was cultured on nutrient agar (NA; Bio-Rad®, France) and then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Using microcentrifuge tube of 1.5 ml, some colonies of each strain were settled into 1 mL of sterile distilled water, heated to 98 °C during 20 min and after that centrifuged at 12,000 rpm. Multiplex PCR procedure was implemented on the supernatant to detect ESBL genes28 and the Shiga toxin genes.24 PCR amplification was achieved according to the following protocol: 1 µL of every primer was added to 12.5 µL Mix (REDTaq® ReadyMixTM PCR re-action mixture with MgCl2. Sigma – Aldrich – Germany) with the addition of 5.5 µL of sterile water and 5 µL of DNA extract. The mixture was finally incubated within the thermocycler with different annealing temperatures for the amplification and identification of the selected genes as shown in Table 1.

Table (1):

Primer’s sequence used to detect ESBL and Shiga toxin genes in the E. coli strains.

| Genes | Primer sequence (5’ – 3’) | Annealing temperature (˚C) | product size (bp) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blaCTX-M | F: ATGTGCAGYACCAGTAARGT R: TGGGTRAARTARGTSACCAGA |

50 | 593 | 24 |

| blaTEM | F: ATGAGTATTCAACATTTCCG R: CTGACAGTTACCAATGCTTA |

58 | 867 | |

| blaSHV | F: GGTTATGCGTTATATTCGCC R: TTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTC |

60 | 867 | |

| blaOXA | F: AATACATATCAACTTCGC R: AGTGTGTTTAGAATGGTGATC |

60 | 885 | |

| stx1 | F: GCGGAAGCGTGGCATTAATACTG R: GCGGAAGCGTGGCATTAATACTG |

63 | 122 | |

| stx2 | F: GATGTTTATGGCGGTTTTATTTGC R: TGGAAAACTCAATTTTACCTTTAGCA |

63 | 83 |

Investigation of the antibacterial potential of plant EOs on the ESBL E. coli strains

Essential oils (EOs)

The EOs were purchased from Hemani International KEPZ, Pakistan. The four EOs; Lettuce, Sesame, Coconut, and Almond were extracted from Lactuca sativa (Batch number: HG-30/390), Sesamum indicum (Batch number: HG-30/302), Cocos nucifera (Batch number: HG-30/306), and Prunus dulcis (Batch number: HG-30/308), respectively. The oils were characterized for their phyto-chemical constituents using Gas Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) in a previous work done by Mezher et al.29 For testing the antibacterial activity, the EOs were half-fold diluted (v/v) with 5% methanol at room temperature to obtain concentrations ranging between 6.25%-

50%. The solutions were homogenized by vortex.

Preparation of the bacterial suspensions

The bacterial suspensions were adjusted by taking a colony of the different E. coli strains then mixing it in tryptone soy broth (TSB) to reach 0.5 McFarland (~108 CFU/mL).

Detection of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) using the broth microdilution technique

MIC for the four EOs against the identified ESBL E. coli strains was detected using the micro-well dilution technique. In sterile 96-well microplates, 90 µL of TSB was introduced into each well with 10 µL of the bacterial cell preparations. After that, 100 µL of the EOs was placed in every well. Then, the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and their optical density (OD) was determined at 595 nm by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) microtiter plate reader. After incubation, MIC was indicated by observing the minimum concentration where no bacterial growth was detected. Subcultures of 10 µL were transferred from the clear wells of the microtiter tray to tryptone soy agar (TSA) plates, then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h for the detection of MBCs which represent the smallest concentration at which no growth for bacteria on antibiotic-free medium.29 In triplicate all the experiments were achieved and then averaged.

Time-kill assay

The time-kill test was done by determining at varying time points the number of existing living bacteria following the submission of EOs. Briefly, 90 µL of TSB was introduced to the wells of 96-well microplates followed by 10 µL of bacterial preparations with 100 µL of MIC × 2 of each EO. Finally, after the incubation of plates at 37 °C, the O.D. was detected by ELISA reader within an interval of time (0-24 h) at 595 nm. The experiment was performed three times.

Antibiofilm activity of EOs against ESBLs E. coli

The ability of different EOs to prevent the biofilm formation and to destroy the pre-formed biofilm of identified ESBL E. coli strains was evaluated.

Inhibition of biofilm formation

The competence of the EOs to inhibit initial cell attachment and biofilm formation was assessed using biofilm inhibition assay. 10 µL of the bacterial suspensions for different ESBL E. coli strains and 90 µL of TSB were introduced within 96-well microtiter plates and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C without agitation. After that, 100 µL of EOs were put in the plate’s wells, then the plates were incubated further at 37 °C during 24 h. Culture medium with no treatment was considered to be negative control. Later, the modified crystal violet (CV) staining method was used in order to estimate the obtained biomass,30 then the absorbance was determined at 595 nm by ELISA microplate reader.31 The experiments were performed three times. The mean value of absorbance was determined for different samples. The equation (1) below32 was applied to find out the percentage inhibition of biofilm.

% of inhibition = (OD of negative control – OD of treated sample) / (OD of negative control) × 100

Negative values reflected the improvement of formation of biofilms and percentage of inhibition exceeding 10% reflected a good prevention of biofilm formation.

Destruction of pre-formed biofilms

For this assay, in each well of 96-well microtiter plates 90 µL of TSB and 10 µL of the standard bacterial preparations were added and then incubated at 37 °C during 30 h in order to permit pre-biofilms formation. Next, 100 µL of the prepared EOs was put in wells, and then plates were incubated during 24 h at 37 °C. Negative control was applied using culture medium without any treatment. Then CV staining test was used to assess the biomass of biofilms and the percentage of eradication was found out in preventing biofilm formation.32 All the experiments were three times repeated for this test.

Statistical analysis

Different graphs and statistical tests were drawn and performed by Excel software (2016) and statistical significance was detected using t-Test. Any difference with p-value smaller than 0.05 was supposed statistically significant.

Biochemical characterization of the ESBL E. coli

Biochemical tests of the different isolated strains identified seven E. coli biotypes. All of them showed the same result in almost of tests except lysine decarboxylase (LDC), ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), sucrose (SAC), and melibiose (MEL) fermentation (Table 2). Most of ODC E. coli strains showed resistance towards Monobactams, Fluoroquinolones, and Cephalosporins in the disk diffusion assay.

Table (2):

Biochemical reactions of E. coli isolates in the API 20 E test

| E. coli strains | Number of strains | aONPG | bADH | cLDC | dODC | eCIT | fH2S | gURE | hTDA | iIND | jVP | kGEL | lGLU | mMAN | nINO | oSOR | pRHA | qSAC | rMEL | sAMY | tARA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season | Site | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Winter | Barada | 2 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | + |

| Sneid | 2 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | |

| Mari | 1 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Spring | Sneid | 2 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Fourzol | 1 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Marj | 1 | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Mansoura | 1 | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Qaraoun | 1 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Summer | Barada | 2 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Sneid | 1 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Fourzol | 2 | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | |

| Marj | 2 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Qaraoun | 1 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Fall | Barada | 1 | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Sneid | 2 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Fourzol | 2 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | |

| Marj | 2 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Mansoura | 2 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| Summer (ESBL) | Sneid | 2 | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | + |

| Mansoura | 2 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | |

| Winter (ESBL) | Fourzol | 2 | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Mansura | 2 | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | ||

a β-galactosidase; b Arginine dihydrolase; c Lysine decarboxylase; d Ornithine decarboxylase; e Citrate utilization; f Hydrogen sulfide production; g Urease; h Tryptophan deaminase; i Indole; j Acetoin (Voges-Proskauer test); k Gelatinase; l Fermentation of glucose; m Mannitol; n Inositol; o Sorbitol; p Rhamnose; q Sucrose; r Melibiose; s Amygdalin and t Arabinose. Red area represents test result that was different from the control strain E. coli ATCC 25922.

Prevalence of MDR E. coli at different sites of the ULRB

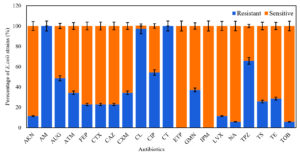

From water samples collected from different sites of the ULRB, 35 strains of E. coli were isolated and examined to test their sensitivity against the previous mentioned antibiotics. All of them revealed resistance to at least 2 from the 20 selected antibiotics and they were considered as MDR strains. The highest resisted antibiotics were Amoxicillin (AM) and Colistin (CT) (100%), followed by Cephalexin (CL) (97.14%), Piperacillin + Tazobactam (TPZ) (65.72%), Ciprofloxacin (CIP) (54.28%), Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (AUG) (48.75%), Gentamicin (GMN) (37.14%), Aztreonam (ATM) (34.28%), Cefuroxime (CXM) (34.28%), and Tetracycline (TE) (28.75%) (Figure 1). Otherwise, E. coli isolates were more susceptible to Tobramycin (TOB) (94.29%), Nalidixic acid (NA) (94.29%) and Levofloxacin (LVX) (88.66%), and no resistance was detected to Imipenem (IPM) and Ertapenem (ETP). The pattern of antibiotic resistance for the identified MDR E. coli strains is presented in Table 3. Our data demonstrate that E. coli strains revealed variable resistance levels, 22.85% (n = 8) of the isolates were resistant to 13-17 antimicrobial categories, most of isolates (57.13%, n = 20) showed resistance to 5-7 categories and 20% (n = 7) of isolates showed resistance to 3 – 4 antimicrobial categories (Table 3).

Table (3):

Percentage of E. coli (n = 35) resistance to 20 antimicrobial categories

Percentage of E. coli resistance (%) (E. coli strains number in water samples) |

Number of resistant antimicrobial categories |

|---|---|

5.71 (2) |

17 |

5.71 (2) |

15 |

11.42 (4) |

13 |

17.14 (6) |

7 |

25.71 (9) |

6 |

14.28 (5) |

5 |

2.85 (1) |

4 |

17.14 (6) |

3 |

Figure 1. Antibiotic resistance rate (%) for the E. coli strains (n = 35) isolated from different water samples against 20 antibiotics

Phenotypic detection of ESBL producers

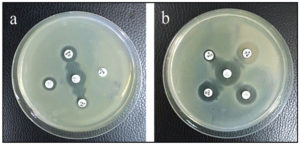

Among the isolated E. coli, 22.8% (8/35) were confirmed to be ESBL producing organisms using Double Disc Synergy Test (DDST). In 2 of them, Cefepime and Aztreonam showed synergism with Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid (Figure 2a) by exhibiting a remarked extension in the margin of inhibition zone made by Cefepime and Aztreonam towards Amoxicillin-Clavulanate disk and no inhibition zone was detected in both Ceftriaxone and Ceftazidime. In the remaining ESBL E. coli, all the antibiotics Ceftriaxone, Ceftazidime, Aztreonam, and Cefepime showed synergism with Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid with noticed expansion in the margin of the inhibition zone produced by all of them toward Amoxicillin-Clavulanate disk (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. DDST showing synergism of (a) ATM and FEP with AMC and (b) CTX, CAZ, ATM, and FEP with AMC (AMC: Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid, CAZ: Ceftazidime, CTX: Ceftriaxone, ATM: Aztreonam and FEP: Cefepime)

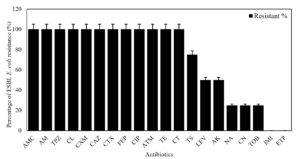

Antibiotic sensitivity patterns for the identified ESBL E. coli

All 8 ESBL E. coli strains showed 100% resistance to Penicillin, Monobactams, Cephalosporins, Tetracycline, Colistin, and Ciprofloxacin. Otherwise, these strains revealed 100% susceptibility to Carbapenems (Imipenem and Ertapenem). Most of them were sensitive to Nalidixic acid (n = 6; 75%, 6/8), Gentamicin (n = 6; 75%, 6/8), Tobramycin (n = 6; 75%, 6/8), Amikacin (n = 4; 50%, 4/8), and Levofloxacin (n = 4; 50%, 4/8) (Figure 3).

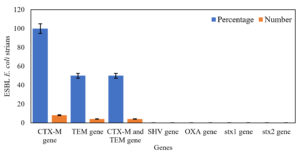

Molecular detection of ESBL producer genes and Shiga toxin genes in ESBL E. coli

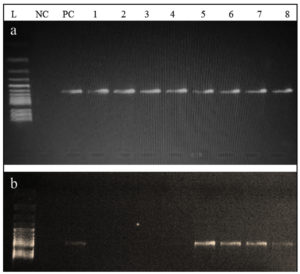

From all ESBL E. coli strains (n = 8), blaCTX-M gene was detected in 100% (n = 8) of the strains, both blaCTX-M and blaTEM genes were identified in 50% (n = 4), and neither blaOXA nor blaSHV gene was identified in all strains (Figure 4). Both blaCTX-M and blaTEM genes were identified on agarose gel (1.5%) using ultraviolet (UV) light and a band of product size 593 bp and 867 bp, respectively (Figure 5a and b). On the other hand, no Shiga toxin genes were identified (neither stx1 nor stx2) in all of ESBL E. coli strains.

Figure 5. Agarose gel showing the (a) 593 bp PCR bands for the CTX-M gene and (b) 867 bp PCR bands for the TEM gene from the ESBL E. coli isolates; L: Leader marker (100 bp); NC: Negative control; PC: positive control (K. pneumoniae 098); 1,2,3,4 are positive for CTX-M and 5,6,7,8 are positive for CTX-M and TEM positive ESBL E. coli

Oil susceptibility patterns of the ESBL producing E. coli strains

Determination of the MIC and MBC for the examined EOs against the ESBL E. coli strains

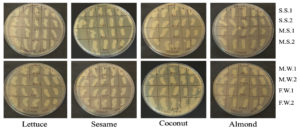

8 strains from the isolated ESBL E. coli were assessed to detect their sensitivity to different EOs. The MICs and MBCs are summarized in Table 4 and listed for each strain. The results showed that Sesame oil showed the greatest bacteriostatic and bactericidal effect by inhibiting the growth of 4 strains, Mansoura Summer 1 (M.S.1) and Mansoura Summer 2 (M.S.2) with MIC of 25%, and Sneid Summer 2 (S.S.2) and Mansoura Winter 2 (M.W.2) with MIC of 50% (Figure S1) and destructing 2 strains M.S.1 and M.S.2 with MBC of 50% (Figure 6), followed by Coconut oil showing bacteriostatic effect against 3 strains, S.S.2 (MIC = 25%), M.S.1 (MIC = 50%), and Fourzol Winter 1 (F.W.1, MIC = 6.25%), but with no bactericidal effect against any strain. Lettuce oil didn’t affect any of 6 strains out of 8 of the ESBL E. coli. However, a bacteriostatic effect was observed against 2 strains, Sneid Summer 1 (S.S.1) and Mansoura Winter 1 (M.W.1) with MIC of 50% and 25%, respectively (Figure S1). A bactericidal effect of Lettuce oil was detected against one strain, M.W.1 with MBC of 50% (Figure 6). Almond oil showed the lowest bacteriostatic effect by affecting only one strain, M.S.1 with MIC of 50% (Figure S1) and with no bactericidal effect.

Table (4):

MICs, MBCs, and MBC/MIC ratio of the lettuce, sesame, coconut, and almond EOs against ESBL E. coli isolates

| ESBL E. coli strains | EOs’ MICs and MBCs (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lettuce | Sesame | Coconut | Almond | |||||||||

| MIC | MBC | MBC/MIC | MIC | MBC | MBC/MIC | MIC | MBC | MBC/MIC | MIC | MBC | MBC/MIC | |

| S.S.1 | 50 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| S.S.2 | ND | ND | ND | 50 | ND | ND | 25 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M.S.1 | ND | ND | ND | 25 | 50 | 2 | 50 | ND | ND | 50 | ND | ND |

| M.S.2 | ND | ND | ND | 25 | 50 | 2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M.W.1 | 25 | 50 | 2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M.W.2 | ND | ND | ND | 50 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| F.W.1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 6.25 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| . F W.2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

EOs: Essential oils, MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration, MBC: Minimum bactericidal concentration, ESBL: Expended-spectrum beta-lactamase, S.S.1: Sneid Summer 1, S.S.2: Sneid Summer 2, M.S.1: Mansoura Summer 1, M.S.2: Mansoura Summer 2, F.W.1: Fourzol Winter 1, F.W.2: Fourzol Winter 2, ND: Not determined.

Figure 6. MBC resultant of the lettuce, sesame, coconut, and almond EOs against the ESBL E. coli; S.S.1: Sneid Summer 1, S.S.2: Sneid Summer 2, M.S.1: Mansoura Summer 1, M.S.2: Mansoura Summer 2, F.W.1: Fourzol Winter 1, F.W.2: Fourzol Winter 2

Effect of the EOs by quantifying bacterial growth (Time-kill test)

The effect of EOs on microbial viability was tested using the time kill assay. The test was done without (control) or with EOs (concentrations equal to 2 x MIC) and the growth of ESBL E. coli isolates was detected within an interval of time between 0 and 24 h. The control strains without EOs showed a normal growth curve. While in the presence of EOs, different inhibitory effects were observed according to each type of EO (Figure S2). Sesame oil showed the highest bactericidal effect with a wide inhibitory effect detected over the bacterial growth of 5 strains over 8 with different time of inhibition ranging between 1- 3 h, followed by coconut oil by inhibiting the growth of three bacterial strains S.S.2, M.S.1, F.W.1 after three, two, and one hour, respectively, supporting the results of the MIC assay. Then for Almond oil, an inhibitory effect was observed over microbial growth of only 1 strain (M.S.1), 1 h after the beginning of the test and Lettuce oil inhibited the microbial growth of just 2 strains (S.S.1 and M.W.1) after 2 h of the beginning of the test (Table 5).

Table (5):

Time of inhibition of the Lettuce, Sesame, Coconut, and Almond EOs against the ESBL E. coli

| Bacterial isolates | Time of inhibition (h) of the Eos | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lettuce | Sesame | Coconut | Almond | |

| S.S.1 | 2 | – | – | – |

| S.S.2 | – | 2 | 3 | – |

| M.S.1 | – | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| M.S.2 | – | 1 | – | – |

| M.W.1 | 2 | – | – | – |

| M.W.2 | – | 3 | – | – |

| F.W.1 | – | – | 1 | – |

| F.W.2 | – | 2 | – | – |

EOs: Essential oils, S.S.1: Sneid Summer 1, S.S.2: Sneid Summer 2, M.S.1: Mansoura Summer 1, M.S.2: Mansoura Summer 2, F.W.1: Fourzol Winter 1, F.W.2: Fourzol Winter 2

Antibiofilm activity results

Inhibition of biofilm formation

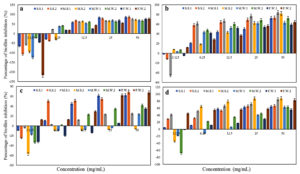

The EOs showed different levels of inhibition of bacterial attachment and biofilm formation. Almond, Sesame, and Lettuce oils (50% concentration) showed good prevention of the growth of all ESBL E. coli strains with percentage of inhibition >50% (Figure 7). Coconut oil (50% concentration) showed the lowest antibiofilm formation effect by enhancing the biofilm formation for M.S.2 (according to the detected negative percentage of inhibition), with inhibition less than 50% against 4 strains (M.S.1, M.W.1, M.W.2, and F.W.1), and good prevention of biofilm formation for only 3 strains S.S.1, S.S.2, and F.W.2 with percentage of inhibition >50% (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Biofilm formation inhibition of ESBL producing E. coli by (a) Lettuce, (b) Sesame, (c) Coconut, and (d) Almond EOs

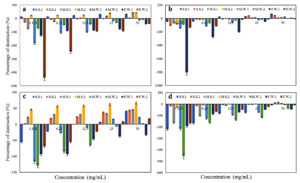

Destruction of pre-formed biofilms

The EOs showed different degrees of activity on the reduction of further biofilm development as shown in Figure 8. Coconut oil showed the highest effect on preformed biofilms with significant activity (percentage of destruction >50%) against M.S.2, and with different percentages of destruction: 40.59%, 43.87%, 44.87%, 21.51%, 2.21%, and 17.01% for S.S.1, S.S.2, M.S.1, M.W.1, M.W.2, and F.W.2, respectively, and in contrast enhanced the biofilm formation of F.W.1, followed by Sesame oil by reducing the biofilm formation of S.S1 and S.S.2 with percentage of destruction of 65.39% and 43.15%, respectively, with poor biofilm destruction against the 6 remaining strains and enhancement of the growth for F.W.2. Then, Lettuce oil showed different percentages of destruction against S.S.1, M.S.1, and M.S.2 with 32.82%, 43.08%, and 43.19%, respectively, had a poor biofilm destruction activity against S.S.2 and enhanced the biofilm formation of 4 strains (M.W.1, M.W.2, F.W.1 and F.W.2). Almond oil showed the lowest effect on the preformed biofilms with a poor biofilm destruction activity against 3 strains (S.S.2, M.S.1, and M.S.2) and enhancement of the biofilm formation of the 5 remaining strains (S.S.1, M.W.1, M.W.2, F.W.1, and F.W.2).

This investigation permitted us to assess the occurrence of ESBL producers among strains of E. coli isolated from different sampling sites at the Upper Basin of Litany River in the Beqaa valley of Lebanon, during one year (from spring 2019 to winter 2020).33 The results revealed that 22.8% of E. coli strains were confirmed to be ESBL-producers. MDR ESBL E. coli strains dissemination beside the elevated ABR levels is caused by the excessive usage of extended spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs) from the beginning of 1980.34 The detection level in intensive care units for the ESBL E. coli changed largely in various regions of the world, ranging from 12.8% in Canada35 to 70.6% in Iran.36 In Lebanon, for hospitalized patients, ESBL production in E. coli percentage was 32.3% in 2013. The universal spreading of ESBL-producers is considered as a critical common health alarm over the globe.

The raised domination of main gene types blaCTX-M and blaTEM in ESBL E. coli isolates represent big trouble for scientists and clinicians. Regular follow for antibiotic susceptibility and related genes could be helpful in the guidance of the reasonable use of antibiotics to treat the main bacteria (E. coli) of healthcare and hospital systems.37 This study has been performed to monitor the antibiotic susceptibility profile of MDR E. coli isolated from the URLB as well as to genotype the identified ESBL E. coli for CTX, TEM, SHV, and OXA genes to detect the correlation between these genes and the antibiotic resistance profile of these strains.

In this study, all 35 E. coli isolates were assessed for their sensitivity to 20 antibiotics then tested for ESBL production. All the identified ESBL E. coli strains were MDR. Elevated occurrence of ESBL E. coli beside high rate of resistance to different antibiotics (resistance to 15 till 17 antibiotics over 20) are also reported in this study. Moreover, numerous previous studies showed high percentage (40%-70%) of ESBL E. coli showing multidrug-resistance.38 This multidrug-resistance could be due to several factors such as the absence of control on antibiotic usage, the usage of antibiotics in agricultural purposes, and fake or law quality medicines.39 There is a link between the resistance to certain antibiotic classes and the absence of ornithine decarboxylase activity. Numerous studies conducted over the last years showed a relation between antibiotic resistance and genetic characteristics.40 Moreover, Ferjani et al.41 revealed noticeable correlation among phylogenetic groups, virulence factors, and susceptibility to fluoroquinolones. This investigation is the first in Lebanon to show the relation between the resistance to different classes of antibiotics and biochemical characteristics in E. coli strains isolated from ULRB. Otherwise, all ESBL E. coli strains in this investigation showed susceptibility to both ertapenem and imipenem antibiotics. This goes in line with the result obtained by research achieved in Lebanon by Ghaddar et al.,42 where the isolated ESBL E. coli showed high susceptibility (93.2%) to Imipenem. Furthermore, our investigation focused on the association between the resistance to Penicillins, Cephalosporins, Monobactams, Tetracycline, Colistin, and Ciprofloxacine, and the occurrence of CTX-M and TEM genes in ESBL producers.

At the molecular level and concerning beta-lactamase genes, the majority of researches achieved in Lebanon showed that blaCTX-M was the most frequent gene in ESBL producers.42-44 Similarly, in this investigation the most popular gene in ESBL producing E. coli was blaCTX-M. This gene was found in ESBL E. coli that concurs through different reports showing its excessive spread among ESBL E. coli strains.45 ESBL genotypes blaCTX-M are rapidly dispersed within different environmental sources, human and animals illustrating a critical difficulty in the therapy of this kind of infectious diseases.46 Moreover, it was noticed a multiple carrying of genes within numerous ESBL E. coli strains, the most prevalent genes association was blaCTX-M + blaTEM type. The results of this investigation were in accordance with that where 50% of identified ESBL E. coli showed this combination as well as the research done by Lohani et al., where 21.2% of ESBL producing strains have both blaCTX”M and blaTEM genes.47 However, there was neither detection of blaOXA type E. coli nor blaSHV E. coli which is identical to the finding of research achieved in Nigeria48 where no ESBL E. coli strains were positive to blaSHV gene. Furthermore, in Nepal several researches revealed the spread of blaSHV gene with low rate.47,49 No Shiga toxin genes were detected in all our ESBL strains. Shigella and Salmonella ESBL producers have been detected globally,50 while to our information, until now no ESBL-producing STEC strain has been identified in the Lebanese population or at clinical level in hospitals. This is the first study achieved in Lebanon for the evaluation of Shiga toxin genes prevalence in ESBL E. coli.

ESBL E. coli are highly MDR, this will conduct to huge barriers in the drugs choice to treat and restrict the extension of this strain,51 as well as there were several problems in their treatment specially in Lebanon, due to the overuse of antibiotics in several sectors including agriculture. This necessitates the involvement of experts with various specializations with the intervention of internal organized collaboration at the hospital and local levels with the cover of Lebanese Ministry of Public Health. In point of fact, the genetic characterization of MDR strains gives important information concerning their spread in hospitals and different environments and shows the similarities between animal, human, and environmental bacterial isolates, like that has been accomplished by different Lebanese groups.52,53 However, the increase of ESBL E. coli resistance to most of antibiotic classes and therefore the difficulty in the treatment of infections highlights the need for the discovery of new strategies to be applied with this trouble.

Numerous studies have showed the various biological activities of EOs, their active compounds, and their antibacterial effect against ABR strains of public health concern. These studies confirmed that EOs are more useful than traditional antimicrobial agents against MDR isolates.54 The obtained data in this investigation revealed that all the EOs showed antibacterial effect opposed to all the identified ESBL E. coli strains and Sesame oil was the most effective. Sesame oil has been known as ‘Queen of oils’, characterized by elevated concentration of unsaturated fatty acids like linoleic and oleic acid which improve its ability in the therapy of different bacterial diseases.29,55 Lettuce oil antibacterial activity was favored by the presence of flavones, saponins as well as sterols.56 For Almond oil the ability of disturbing aminoglycoside antibiotic activity was related to its effective myristic, oleic, and lauric fatty acids.56 As well as the advantages and the antibacterial properties of Coconut oil are mainly correlated with the presence of fatty acids.57 The antibacterial effect of the EOs varied significantly among ESBL E. coli strains. The best susceptibility was recorded for Sesame oil followed by Coconut, Lettuce, and Almond showing different bacteriostatic effects. This difference in the antibacterial effect of different EOs is attributable to the variety within the chemical composition of oils. Many previous studies showed the relation that exists between the antibacterial impact of the EOs and their chemical components.58 The time-kill test was done to assess the time required for EOs to achieve their bactericidal effects. This effect was shown by the four used EOs at MIC x 2, at time ranging between 1-3 h and on the different strains with highest effect shown by Sesame oil on 5 strains out of 8. These effects (bacteriostatic and bactericidal) are affected by the composition of the bacterial strain. Numerous authors mentioned that the EO can raise the permeability of bacterial cell membrane, inducing the escape of different cellular organelles then the bacterial cell destruction.59

Almond, Sesame, and Lettuce oils showed an interesting effect opposed to biofilm formation for all ESBL producing E. coli. The blockage of biofilm formation in ESBL E. coli strains identified in this investigation proposes that the inclusion of EOs before formation of biofilm can remove planktonic cells and turn the non-living surface low receptive for the adhesion of bacterial cells.60 Furthermore, a previous investigation affirmed that the application of plant extracts on the surface induces dis-parting of bacteria, consequently diminishing the surface binding and biofilm formation.32 Coconut oil enhanced the biofilm formation for one strain and had a lower antibiofilm effect. Coconut and sesame oils showed significant effect on the pre-formed biofilms of 2 strains, respectively, which can be useful to treat diseases induced by these strains of ESBL E. coli. The anti-biofilm effect of EOs is based on their compounds which work by various mechanisms on the cell viability and biofilm formation. Moreover, the effect of the main constituents in an EO can be affected by its small elements as well as it may change between bacterial species also between various isolates within the same species,61 which was the case in our study, where different effects of the same EO was shown on different strains of ESBL E. coli. Otherwise, our investigation makes known that the ability of the EOs to destroy previous antibiofilm was oil dependent, with different ability of further biofilm reduction. Furthermore, this antibiofilm effect was at different concentrations of the EOs. These findings are compatible with preceding studies stating that the anti-biofilm effects are not concentration-dependent.62 In our study, EOs showed a better effect in avoiding biofilm formation than destructing pre-formed biofilms, like numerous previous investigations.31,63

This investigation concludes that the common frequent resistant gene in different ESBL E. coli strains isolated from different sites along the ULRB was the CTX-M gene, followed by the TEM gene. Furthermore, the elevated rate of CTX-M transmission was leading to the increase of resistance to the third generation of Cephalosporins, Aminoglycosides, and Fluoroquinolones. The potential of these strains of bacteria to conduct plasmid-borne resistance genes to other bacteria has turned a public health trouble. Otherwise, the most successful antimicrobial agent class against the ESBL producers was confirmed to be Carbapenems. Therefore, this investigation clarifies the need of the continuous monitoring of ESBL producers in the areas surrounding the Litany River and reveals the necessity for taking preventive measures to avoid the extension of these MDR strains. Besides, different EOs have been studied to reveal their antimicrobial properties against ESBL producers. This is the first investigation to study the impact of various plant EOs on ESBL E. coli collected from the ULRB. The accomplished results revealed a remarkable variation in the antibacterial effect among the four EOs based on type of oil and bacterial strains on the basis of MIC and MBC values and antibiofilm activity. These results could stimulate further biological research on these EOs, to clarify their mechanisms of action and to be used as antimicrobial agent to prevent bacterial growth and biofilm formation of ESBL E. coli strains. The usage of EOs provides an encouraging method to prevent the proliferation of multidrug-resistant E. coli and meet the vital requirement for successful antimicrobial treatments. EOs have shown remarkable effect against a broad range of bacteria. Investigating developed solutions that contain EO products for medical devices emphasizes their capacity to be used as effective alternatives to synthetic antimicrobial agents.

Additional file: Figure S1-S2.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

MIK conceptualized the study. DB, MH, BH performed data curation. DB, MM, MH, BH, MIK applied methodology. DB, MIK performed investigation. DB, MM, MH, MIK and BH performed formal analysis. DB, MH and BH performed software work. MIK supervised the study. MIK performed data validation. DB wrote the original draft. MM reviewed and edited the original draft. MIK wrote the manuscript. MH, MIK and BH reviewed and edited the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Kraemer SA, Ramachandran A, Perron GG. Antibiotic pollution in the environment: From microbial ecology to public policy. Microorganisms. 2019;7(6):180.

Crossref - Thornber K, Verner-Jeffreys D, Hinchliffe S, Rahman MM, Bass D, Tyler CR. Evaluating antimicrobial resistance in the global shrimp industry. Rev Aquac. 2020;12(2):966-986.

Crossref - Manyi-Loh C, Mamphweli S, Meyer E, Okoh A. Antibiotic use in agriculture and its consequential resistance in environmental sources: Potential public health implications. Molecules. 2018;23(4):795.

Crossref - Peirano G, Pitout JDD. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae: Update on Molecular Epidemiology and Treatment Options. Drugs. 2019;79(14):1529-1541.

Crossref - Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: A clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(4)657-686.

Crossref - D’Andrea MM, Arena F, Pallecchi L, Rossolini GM. CTX-M-type β-lactamases: A successful story of antibiotic resistance. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303(6-7):305-317.

Crossref - Bevan ER, Jones AM, Hawkey PM. Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: Temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(8):2145-2155.

Crossref - Mshana SE, Kamugisha E, Mirambo M, Chakraborty T, Lyamuya EF. Prevalence of multiresistant gram-negative organisms in a tertiary hospital in Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Research Notes. 2009;2:49.

Crossref - Kaur M, Aggarwal A. Occurrence of the CTX-M, SHV and the TEM genes among the extended spectrum β-lactamase producing isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in a tertiary care hospital of north India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(4):642-645.

Crossref - Bruyand M, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Gouali M, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome due to Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection. Med Mal Infect. 2018;48(3):167-174.

Crossref - Bettelheim KA, Beutin L. Rapid laboratory identification and characterization of verocytotoxigenic (Shiga toxin producing) Escherichia coli (VTEC/STEC). J Appl Microbiol. 2003;95(2):205-217.

Crossref - Iwu CD, du Plessis E, Korsten L, Okoh AI. Antibiogram imprints of E. coli O157:H7 recovered from irrigation water and agricultural soil samples collected from two district municipalities in South Africa. Int J Environ Stud. 2021;78(6):940-953.

Crossref - Xie Y, Zhu L, Lyu G, Lu L, Ma J, Ma J. Persistence of E. coli O157:H7 in urban recreational waters from Spring and Autumn: a comparison analysis. Environ Sci Poll Res. 2022;29(26):39088-39101.

Crossref - Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Ongoing multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli serotype O157/ : H7 infections associated with consumption of fresh spinach. Morb Mortality Wkly Rep (MMWR). 2006;55(38):1045-6.

- Ram S, Vajpayee P, Singh RL, Shanker R. Surface water of a perennial river exhibits multi-antimicrobial resistant shiga toxin and enterotoxin producing Escherichia coli. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2009;72(2):490-495.

Crossref - Ishii Y, Kimura S, Alba J, et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Shiga toxin gene (Stx 1)-positive Escherichia coli O26:H11: A new concern. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(3):1072-1075.

Crossref - Rudramurthy GR, Swamy MK, Sinniah UR, Ghasemzadeh A. Nanoparticles: Alternatives against drug-resistant pathogenic microbes. Molecules. 2016;21(7):836.

Crossref - Akthar MS, Degaga B, Azam T. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils extracted from medicinal plants against the pathogenic microorganisms: A review. Biol Sci Pharm Res. 2014;2(1):001-007.

- Oussalah M, Caillet S, Saucier L, Lacroix M. Inhibitory effects of selected plant essential oils on the growth of four pathogenic bacteria: E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control. 2007;18(5):414-420.

Crossref - da Silva JKR, Figueiredo PLB, Byler KG, Setzer WN. Essential oils as antiviral agents. Potential of essential oils to treat sars”cov”2 infection: An in”silico investigation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(10):3426.

Crossref - Gulluce M, Sahin F, Sokmen M, et al. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of the essential oils and methanol extract from Mentha longifolia L. ssp. longifolia. Food Chem. 2007;103(4):1449-1456.

Crossref - Swamy MK, Akhtar MS, Sinniah UR. Antimicrobial properties of plant essential oils against human pathogens and their mode of action: An updated review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016(1):3012462.

Crossref - Kemper MA, Veenman C, Blaak H, Schets FM. A membrane filtration method for the enumeration of Escherichia coli in bathing water and other waters with high levels of background bacteria. J Water Health. 2023;21(8):995-1003.

Crossref - CLSI. In: Gressner A.M., Arndt T. (eds) Lexikon der Medizinischen Laboratoriums diagnostik. Springer Reference Medizin. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Crossref - Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). CLSI M07; Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, Wayne, PA.2018. https://clsi.org/shop/standards/m07/

- Englen MD, Kelley LC. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for the identification of Campylobacter jejuni by the polymerase chain reaction. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2000;31(6):421-426.

Crossref - Dallenne C, da Costa A, Decre D, Favier C, Arlet G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(3):490-495.

Crossref - Yoshitomi KJ, Jinneman KC, Weagant SD. Detection of Shiga toxin genes stx1, stx2, and the +93 uidA mutation of E. coli O157:H7/H-using SYBR® Green I in a real-time multiplex PCR. Mol Cell Probes. 2006;20(1):31-41.

Crossref - Mezher M, Hajj RE, Khalil M. Investigating the antimicrobial activity of essential oils against pathogens isolated from sewage sludge of southern Lebanese villages. Germs. 2022;31;12(4):488-506.

Crossref - Djordjevic D, Wiedmann M, McLandsborough LA. Microtiter plate assay for assessment of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68(6):2950-2958.

Crossref - Famuyide IM, Aro AO, Fasina FO, Eloff JN, McGaw LJ. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of acetone leaf extracts of nine under-investigated south African Eugenia and Syzygium (Myrtaceae) species and their selectivity indices. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):141.

Crossref - Sandasi M, Leonard CM, Viljoen AM. The effect of five common essential oil components on Listeria monocytogenes biofilms. Food Control. 2008;19(11):1070-1075.

Crossref - Bohlok D, Mezher M, Houshaymi B, Fakhoury M, Khalil MI. Microbiological and physicochemical water quality assessments of the Upper Basin Litany River, Lebanon. Environ Monit Assess. 2025;197(1):74.

Crossref - Rawat D, Nair D. Extended-spectrum -lactamases in gram negative bacteria. J Glob Infect Dis. 2010;2(3):263-274.

Crossref - Zhanel GG, DeCorby M, Laing N, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens in intensive care units in Canada: Results of the Canadian National Intensive Care Unit (CAN-ICU) study, 2005-2006. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(4):1430-1437.

Crossref - Ashrafian F, Askari E, Kalamatizade E, Ghabouli-Shahroodi M, Naderi-Nasab M. The Frequency of Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamase (ESBL) in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: A Report from Mashhad, Iran. J Med Bacteriol. 2013;2(1,2).12-19.

- Pishtiwan AH, Khadija KM. Prevalence of blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M genes among ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolated from thalassemia patients in Erbil, Iraq. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases. 2019;11(1):e2019041.

Crossref - Khanal LK, Amatya R, Sah AK, et al. Prevalence of Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamase producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. from urinary specimen in a tertiary care hospital. Nepal Medical College Journal. 2022;24(1):75-80.

Crossref - Tanwar J, Das S, Fatima Z, Hameed S. Multidrug resistance: An emerging crisis. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2014;2014(1):541340.

Crossref - Bashir S, Sarwar Y, Ali A, et al. Multiple drug resistance patterns in various phylogenetic groups of uropathogenic E. coli isolated from Faisalabad region of Pakistan. Braz J Microbiol. 2011;42(4):1278-1283.

Crossref - Ferjani S, Saidani M, Ennigrou S, Hsairi M, Ben Redjeb S. Virulence determinants, phylogenetic groups and fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from cystitis and pyelonephritis. Pathol Biol. 2012;60(5):270-274.

Crossref - Ghaddar N, Anastasiadis E, Halimeh R, et al. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases Produced by Escherichia coli Colonizing Pregnant Women. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2020;2020(1):4190306.

Crossref - Kanj SS, Corkill JE, Kanafani ZA, et al. Molecular characterisation of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates at a tertiary-care centre in Lebanon. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(5):501-504.

Crossref - Mansour R, El-Dakdouki MH, Mina S. Phylogenetic group distribution and antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli isolates in aquatic environments of a highly populated area. AIMS Microbiol. 2024;10(2):340-362.

Crossref - Canton R, Gonzalez-Alba JM, Galan JC. CTX-M enzymes: Origin and diffusion. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:110.

Crossref - Wang J, Ma ZB, Zeng ZL, Yang XW, Huang Y, Liu JH. The role of wildlife (wild birds) in the global transmission of antimicrobial resistance genes. Zool Res. 2017;38(2):55-80.

Crossref - Lohani B, Thapa M, Sharma L, et al. Predominance of CTX-M Type Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) Producers Among Clinical Isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in a Tertiary Care Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. Open Microbiol J. 2019;13(1):13-28.

Crossref - Adekanmbi AO, Akinpelu MO, Olaposi AV, Oyelade AA. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase encoding gene-fingerprints in multidrug resistant Escherichia coli isolated from wastewater and sludge of a hospital treatment plant in Nigeria. Int J Environ Stud. 2020;78(1):140-150.

Crossref - Parajuli NP, Maharjan P, Joshi G, Khanal PR. Emerging Perils of Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Clinical Isolates in a Teaching Hospital of Nepal. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016(1):1782835.

Crossref - Aitmhand R, Soukri A, Moustaoui N, et al. Plasmid-mediated TEM-3 extended-spectrum β-lactamase production in Salmonella typhimurium in Casablanca. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49(1):169-172.

Crossref - Rath S, Dubey D, Sahu MC, Debata NK, Padhy RN. Surveillance of ESBL producing multidrug resistant Escherichia coli in a teaching hospital in India. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2014;4(2):140-149.

Crossref - Hammoudi D, Moubareck CA, Hakime N, et al. Spread of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii co-expressing OXA-23 and GES-11 carbapenemases in Lebanon. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;36:56-61.

Crossref - Hammoudi D, Moubareck AC, Kanso A, Nordmann P, Sarkis DK. Surveillance of carbapenem non-susceptible gram negative strains and characterization of carbapenemases of classes A, B and D in a Lebanese hospital. J Med Liban. 2015;63(2):66-73.

Crossref - Tariq S, Wani S, Rasool W, et al. A comprehensive review of the antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral potential of essential oils and their chemical constituents against drug-resistant microbial pathogens. Microb Pathog. 2019;134:103580.

Crossref - Uzun B, Arslan C, Furat S. Variation in fatty acid compositions, oil content and oil yield in a germplasm collection of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2008;85(12):1135-1142.

Crossref - Machado JF, Costa MDS, Tintino SR, et al. Antibiotic activity potentiation and physicochemical characterization of the fixed orbignya speciosa almond oil against mdr Staphylococcus aureus and other bacteria. Antibiotics. 2019a;8(1):28.

Crossref - Dufour M, Manson JM, Bremer PJ, Dufour JP, Cook GM, Simmonds RS. Characterization of monolaurin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(17):5507-5515.

Crossref - El-Jalel LFA, Elkady WM, Gonaid MH, El-Gareeb KA. Difference in chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Thymus capitatus L. essential oil at different altitudes. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2018;4(2):156-160.

Crossref - Oussalah M, Caillet S, Lacroix M. Mechanism of action of Spanish oregano, Chinese cinnamon, and savory essential oils against cell membranes and walls of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Listeria monocytogenes. J Food Protect. 2006;69(5):1046-1055.

Crossref - Liaqat I, Asgar A. Antimicrobial potential of eucalyptus oil and lemongrass oil alone and in combination against clinical bacteria in planktonic and biofilm mode. World J Biol Biotechnol. 2021;6(1).

Crossref - Cacciatore I, Di Giulio M, Fornasari E, et al. Carvacrol codrugs: A new approach in the antimicrobial plan. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):120937.

Crossref - Aires A, Barreto AS, Semedo-Lemsaddek T. Antimicrobial effects of essential oils on oral microbiota biofilms: The toothbrush in vitro model. Antibiotics. 2021;10(1):21.

Crossref - Iseppi R, Tardugno R, Brighenti V, et al. Phytochemical composition and in vitro antimicrobial activity of essential oils from the lamiaceae family against Streptococcus agalactiae and Candida albicans biofilms. Antibiotics. 2020;9(9):592.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.