ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

The vaginal microbiota is a critical component of female reproductive and urogenital health, predominantly maintained by Lactobacillus species. These bacteria play a vital role in sustaining a low vaginal pH by producing lactic acid and antimicrobial substances, providing natural defense against pathogenic colonization. The hormonal alterations linked to menopause, especially the reduction in oestrogen levels, significantly influence the composition and stability of the vaginal microbiome, making women vulnerable to infections and inflammation. This investigation sought to assess and contrast the vaginal microbiome composition in women before and after menopause. Using Gram-stain microscopy, conventional culture methods, and molecular techniques, specifically Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), to assess Lactobacillus abundance and the prevalence of pathogenic bacteria. A comparative cross-sectional study was conducted by comparing two groups of women: 40 premenopausal and 40 postmenopausal, for a total of 80 participants. Vaginal swabs were collected and subjected to Gram staining, culture on selective media for Candida spp., and PCR/qPCR analysis to detect and quantify key bacterial species, including Lactobacillus spp., Gardnerella vaginalis, and Atopobium vaginae. SPSS Version 25 was employed for conducting. The statistical analysis yielded data viewed significant at p < 0.05. Microscopic observation revealed that 85% of premenopausal women had Nugent scores indicating a healthy Lactobacillus-dominated microbiota, while only 35% of postmenopausal women showed similar results. PCR and qPCR analyses demonstrated a significant reduction in Lactobacillus spp. in postmenopausal women, with Lactobacillus crispatus copy numbers declining from 4.5 × 10¹¹ to 1.2 × 10¹¹ copies/mL. Conversely, pathogenic bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis and Prevotella spp. increased significantly in postmenopausal women. Additionally, Candida spp. colonization was high in the postmenopausal group (15%) compare to the premenopausal group (5%). The findings confirm a significant shift in vaginal microbiota composition due to menopausal hormonal changes. The depletion of Lactobacillus spp. and the concurrent rise in pathogenic bacteria in postmenopausal women underscore the need for targeted interventions, such as probiotic therapies or hormone replacement treatments, to restore microbial balance and reduce infection risks.

Vaginal Microbiota, Lactobacillus Species, Menopause, Bacterial Vaginosis, Candida spp., PCR, qPCR, Gardnerella vaginalis, Vaginal Dysbiosis, Hormonal Changes

The human vaginal microbiome is essential for preserving women’s reproductive and general urogenital health. A healthy vaginal environment is primarily defined by the prevalence of Lactobacillus species, especially L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. jensenii, and L. iners. These advantageous bacteria are crucial for sustaining a low vaginal pH (~3.5-4.5) by generating lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and several antibacterial agents. The acidic environment functions as a natural defence mechanism, inhibiting the colonisation and proliferation of harmful and opportunistic bacteria.1

However, the vaginal microbiota is dynamic and experiences substantial alterations during a woman’s life due to several physiological circumstances, including hormone variations, menstrual cycles, pregnancy, and particularly, menopause. The transition to menopause is marked by a sharp decline in estrogen levels, which directly affects the vaginal ecosystem. Estrogen promotes the accumulation of glycogen in the vaginal epithelium, providing a vital substrate for Lactobacillus growth. As estrogen levels drop during menopause, glycogen availability diminishes, leading to a reduction in Lactobacillus populations. This decline in protective bacteria alters the vaginal environment, resulting in increased pH and microbial dysbiosis.2

Postmenopausal women frequently have a more varied and less stable vaginal microbiota, marked by the proliferation of pathogenic and anaerobic bacteria, including Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella species, and Atopobium vaginae. The changes in microbial composition are related with a higher chance of developing vaginal disorders, such as BV, VVC, and UTIs. Additionally, the weakened mucosal immunity and reduced epithelial integrity in postmenopausal women further exacerbate susceptibility to infections and inflammation, negatively impacting quality of life.3

Despite advancements in understanding vaginal microbiota composition, there remains a gap in comprehensive research focusing on the quantitative and qualitative differences in the vaginal microbiome between premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Most existing studies primarily rely on traditional culture methods, which are limited in detecting fastidious or unculturable microorganisms. Molecular methods, particularly Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), provide superior sensitivity and specificity for the identification and quantification of bacterial species, encompassing both cultivable and non-cultivable microbes.4

This study seeks to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the vaginal microbiota composition in premenopausal and postmenopausal women utilising sophisticated molecular methods, namely real-time PCR, to quantify Lactobacillus species and detect significant pathogenic bacteria. Additionally, the study incorporates traditional culture-based methods to detect fungal pathogens like Candida spp., providing a comprehensive microbiological assessment. By understanding species-level differences and microbial shifts associated with menopause, this study seeks to elucidate the role of hormonal changes in shaping vaginal health and to highlight potential microbial markers for disease susceptibility.

This study’s findings will provide significant insights into the impact of menopausal hormone changes on vaginal microbial dynamics. Comprehending these distinctions is crucial for formulating preventative and therapeutic strategies, like probiotic supplements or hormone replacement therapy (HRT), to re-establish a healthy vaginal microbiota and mitigate the risk of infections in postmenopausal women. Additionally, the study’s use of advanced molecular diagnostics may pave the way for more accurate, targeted treatments for vaginal health management.

This research aims to bridge the gap in microbiological understanding between reproductive and post-reproductive stages, offering a foundation for future studies focused on improving women’s reproductive and urogenital health.

Study design and population

This comparative cross-sectional study was designed to assess and compare the vaginal microbiota of premenopausal and postmenopausal women through a combination of conventional microbiological techniques and advanced molecular methods. A total of 80 participants were recruited from outpatient gynecology clinics following strict inclusion and exclusion criteria to minimize confounding factors.5 The study population consisted of two groups: Premenopausal women aged 18 to 45 years and postmenopausal women aged 50 to 70 years. Prior to the collection of the sample, each individual provided written informed consent. The Institutional Ethics Committee granted ethical approval, attesting to the study’s compliance with standards for human research ethics.

Inclusion criteria included women without any active vaginal infections, no antibiotic, antifungal, or probiotic usage in the last 4 weeks, and absence of sexually transmitted infections. Women who were pregnant, on hormone replacement therapy (HRT), or had used vaginal medications or douches within the past month were excluded. This strict participant selection ensured the reliability of the results by minimizing external influences on vaginal microbiota.6

Sample collection

Vaginal samples were collected by trained healthcare professionals under aseptic conditions. A sterile vaginal brush was inserted into the posterior vaginal fornix to collect epithelial cells and mucus. The swab was promptly submerged in sterile tubes having 1 mL of sterile 0.9% NaCl solution. To maintain microbial viability, the collected samples were transferred to the microbiology laboratory on ice within a two-hour timeframe.7

In the laboratory, the saline suspension was divided into separate aliquots designated for microscopy, fungal and bacterial culture, and DNA extraction for molecular analysis. This approach allowed comprehensive analysis through multiple methodologies.

Microscopy and gram staining

Gram staining was performed to provide an initial assessment of the vaginal microbiota composition. A drop of the saline suspension was applied on a grease-free glass slide, air-dried, then heat-fixed, and stained using the Gram staining technique. Microscopic evaluation was conducted under oil immersion (1000× magnification).8

Smears were interpreted based on the following diagnostic criteria:

- Nugent Scoring System for identifying Bacterial Vaginosis (BV), which categorizes bacterial morphotypes into Lactobacillus, Gardnerella, and Mobiluncus.

- Donders Criteria for diagnosing Aerobic Vaginitis (AV), focusing on the presence of toxic leukocytes and disrupted vaginal flora.

- Marot-Leblond Criteria for identifying Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC), detecting yeast cells and pseudohyphae.

Additionally, wet mount preparations were examined under phase-contrast microscopy (400× magnification) to detect hyphal forms indicative of fungal infections.

Culture of Candida spp.

100 µL of the vaginal saline suspension was inoculated onto three types of media to detect and identify the Candida species

Various culture media for microbial growth:

- 5% Human Blood Agar (HBA) supports general fungal cultivation

- Chocolate Agar, prepared by heating human blood agar, is suitable for demanding microorganisms

- Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) specifically promotes fungal growth

For 48 hours, at 37 °C, the plates were incubated aerobically. Colony morphology was noted, and isolates were subjected to Gram staining, catalase, and oxidase tests for preliminary identification. Further differentiation was achieved using PCR-based identification.9

DNA extraction

Using the Cobas® 4800 equipment (Roche Molecular Systems Inc., USA), genomic DNA was extracted from vaginal samples in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. This automated system ensures efficient and contamination-free DNA isolation.10

A Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Nabi, Microdigital) was utilized to assess the quality and quantity of the DNA extract. The DNA’s purity was determined by examining the A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios. The DNA samples were then diluted to 20 ng/µL using molecular-grade water and stored at -20 °C for subsequent use.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for bacterial detection

Species-specific conventional PCR was utilised to discover and identify key vaginal bacterial species, both commensal and pathogenic. PCR reactions were prepared in a 20 µL volume including GoTaq® DNA Polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl2, species-specific primers, and template DNA.11

The PCR thermal cycling protocol commenced with an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 29 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at a primer-specific temperature for 30 seconds, and extension at 72 °C for 1 minute. The amplification process concluded with a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 minutes to ensure complete synthesis of the PCR products. The resulting PCR products were analyzed using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining for visualization.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) for Lactobacillus quantification

The quantification of Lactobacillus spp. was conducted using qPCR with particular primers that target the 16S rRNA gene. A standard curve was established by successive dilutions of Lactobacillus gasseri to quantify bacterial burden.12

The reaction mixture, totaling 20 µL, was composed of:

- GoTaq® Master Mix qPCR (Promega)

- Primers at a concentration of 0.5 µM each

- DNA template amounting to 2 µL

The thermal cycling process consisted of:

A 2-minute initial denaturation step at 94 °C

40 cycles comprising:

- Denaturation: 30 seconds at 94 °C

- Annealing: 30 seconds at 62 °C

- Extension: 1 minute at 72 °C

- A melt curve analysis to verify specificity.

Statistical analysis

SPSS Version 25 was used to analyse the data. Independent t-tests were employed to analyse variations in the bacterial burden. Statistical significance was determined for p-values below 0.05.

Study population characteristics

This research encompassed a total of 80 women, divided equally into two groups: 40 premenopausal and 40 postmenopausal women. The regular age of the premenopausal group was 34.2 ± 5.1 years. The postmenopausal cohort exhibited a mean age of 59.1 ± 4.8 years. Both groups were comparable in terms of demographic and lifestyle factors such as body mass index (BMI), sexual activity, and personal hygiene practices, minimizing potential confounding variables. Postmenopausal women reported a higher incidence of vaginal symptoms, including dryness, itching, and burning sensations, as well as more frequent urinary tract infections, whereas premenopausal women largely reported no such issues, reflecting a healthier vaginal environment.

Microscopic evaluation of vaginal smears

Microscopic analysis of Gram-stained vaginal smears was performed to assess the composition of the vaginal microbiome. The Nugent scoring system was used to classify the samples. In the premenopausal group, 85% of women had Nugent scores between 0 and 3, indicating a healthy, Lactobacillus-dominated vaginal microbiota. Only 10% of premenopausal women had intermediate Nugent scores (4-6), suggesting a slight microbial imbalance, while 5% had scores between 7 and 10, indicative of bacterial vaginosis. In contrast, the postmenopausal group displayed a significant shift in microbiota composition. Only 35% of postmenopausal women maintained Nugent scores within the 0-3 range, while 40% exhibited scores between 7 and 10, consistent with bacterial vaginosis, and 25% had intermediate scores. Microscopic examination of Gram-stained samples from women after menopause showed a significant decrease in Gram-positive Lactobacillus rods and a corresponding increase in Gram-negative microorganisms, including both cocci and bacilli. Wet mount microscopy further supported these findings, with postmenopausal women showing increased leukocytes, parabasal epithelial cells, and a diminished Lactobacillus presence, indicating a transition to dysbiosis and inflammation.

Culture results for Candida spp.

Culture-based analysis of Candida species showed notable differences between the two groups. In the premenopausal group, Candida spp. were isolated in 5% of cases, predominantly Candida albicans, with no significant growth of non-albicans species. In the postmenopausal group, Candida colonization was higher, with 15% of women testing positive. Candida albicans remained the most common isolate, but 5% of cases also showed colonization by Candida glabrata. The findings suggest a reduced presence of Lactobacillus spp. in postmenopausal women may facilitate fungal overgrowth due to a disrupted vaginal environment and elevated pH levels.

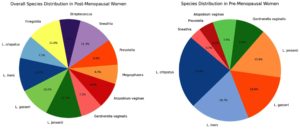

PCR detection of bacterial species

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis provided more detailed insights into the bacterial composition of the vaginal microbiota. In the premenopausal group, Lactobacillus crispatus was detected in 70% of samples, Lactobacillus iners in 60%, and Lactobacillus gasseri in 50%. Pathogenic bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis were detected in only 10% of samples, and Atopobium vaginae in 5%. However, in the postmenopausal group, the prevalence of Lactobacillus species was considerably lower, with Lactobacillus crispatus detected in only 25% of samples, Lactobacillus iners in 20%, and Lactobacillus gasseri in 15%. Conversely, the detection of pathogenic bacteria was markedly higher in the postmenopausal group, with Gardnerella vaginalis found in 45% of samples and Atopobium vaginae in 35%. These results confirm a clear shift from a Lactobacillus-dominated community in premenopausal women to a more diverse and pathogenic microbiota in postmenopausal women (Figure 1).

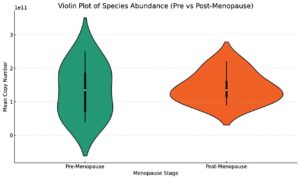

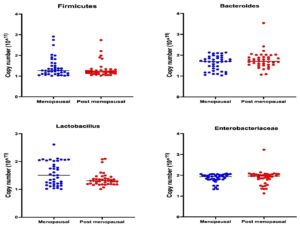

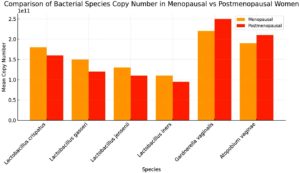

Quantification of Lactobacillus spp. by quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

qPCR further quantified the decline in beneficial bacteria and the rise in pathogenic bacteria. Lactobacillus crispatus exhibited a significant drop in copy number, averaging 4.5 × 10¹¹ copies/mL in the premenopausal group and only 1.2 × 10¹¹ copies/mL in the postmenopausal group. Lactobacillus gasseri decreased from 2.0 × 1011 copies/mL to 0.5 × 1011 copies/mL, and Lactobacillus iners dropped from 2.5 × 1011 copies/mL to 0.8 × 1011 copies/mL (Figure 2). In contrast, pathogenic bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis increased from 0.3 × 1011 copies/mL in premenopausal women to 2.5 × 1011 copies/mL in postmenopausal women. Prevotella spp. increased from 0.4 × 1011 copies/mL to 3.0 × 1011 copies/mL. This dramatic shift in microbial populations indicates a progression toward vaginal dysbiosis following menopause (Figures 3 and 4).

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons revealed notable variations between the two groups in regard to Lactobacillus abundance and pathogenic bacterial load. A statistically significant decrease in Lactobacillus species was observed (p < 0.001). Additionally, a statistically significant rise in Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella spp., and Atopobium vaginae among women after menopause (p < 0.001). Candida colonization was notably higher in postmenopausal women (p = 0.02), supporting the hypothesis that hormonal changes and microbial imbalance contribute to increased fungal colonization.

Interpretation of results

The results clearly demonstrate that menopause significantly alters the vaginal microbiota. Premenopausal women maintain a protective Lactobacillus-dominated environment, primarily consisting of Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus iners, and Lactobacillus gasseri. This microbiota effectively maintains low vaginal pH and inhibits pathogenic colonization. In contrast, postmenopausal women experience a marked depletion of Lactobacillus species and a corresponding overgrowth of pathogenic and anaerobic bacteria, including Gardnerella vaginalis and Prevotella species. This dysbiotic state elevates the vaginal pH and increases susceptibility to infections such as bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis.

The decline in estrogen during menopause seems to be particularly important in this microbial shift by reducing glycogen levels in the vaginal epithelium, thereby limiting nutrients for Lactobacillus growth. These findings highlight the necessity of implementing specific therapies, such as probiotic supplements or hormone replacement therapy, to re-establish microbial equilibrium and enhance vaginal health in postmenopausal women.

Research examining the vaginal microbiome in women before and after menopause reveals crucial information about the substantial alterations in microbial communities that result from the hormonal changes accompanying menopause. The results indicate a marked transition from a Lactobacillus-dominated microbiota in premenopausal women to a more diverse and potentially pathogenic microbiota in postmenopausal women. This transition is categorised by a significant reduction in beneficial Lactobacillus species and an increase in pathogenic bacteria, which has important implications for women’s health.13-15 The demographic characteristics of the study population revealed that both groups were comparable in terms of body mass index (BMI), sexual activity, and personal hygiene practices. However, the postmenopausal group reported a higher incidence of vaginal symptoms such as dryness, itching, and burning sensations, as well as a greater frequency of urinary tract infections. This aligns with existing literature that suggests menopause is related with vaginal atrophy and increased susceptibility to infections due to hormonal changes, particularly the decline in estrogen levels.16,17 Microscopic evaluation of vaginal smears using the Nugent scoring system demonstrated that the majority of premenopausal women maintained a healthy vaginal microbiota characterized by low Nugent scores, indicating a predominance of Lactobacillus species. In contrast, the postmenopausal group exhibited a significant shift, with a notable increase in Nugent scores indicative of bacterial vaginosis. The reduction in Gram-positive Lactobacillus rods and the increase in Gram-variable and Gram-negative organisms in postmenopausal women highlight a transition to dysbiosis, which is often associated with inflammation and increased risk of infections.18,19 Culture results for Candida species further illustrated the differences between the two groups. The prevalence of Candida colonization was higher in postmenopausal women, suggesting that the reduced presence of Lactobacillus spp. may facilitate fungal overgrowth due to a disrupted vaginal environment and elevated pH levels. This finding is significant as it indicates that the hormonal changes associated with menopause not only affect bacterial populations but also create conditions conducive to fungal infections.20,21 PCR detection of bacterial species provided a more detailed understanding of the microbial composition. The significant decrease in Lactobacillus species in postmenopausal women, particularly Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus iners, and Lactobacillus gasseri, was accompanied by a marked increase in pathogenic bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae. These results confirm a clear shift from a dominant Lactobacillus community to a more diverse and pathogenic microbiota, which is concerning given the relationship of these pathogens with increased risk of bacterial vaginosis and urinary tract infections.22,23 Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis further quantified the changes in microbial populations, indicating a significant decrease in the copy numbers of Lactobacillus species in postmenopausal women. In contrast, the copy numbers of pathogenic bacteria including Gardnerella vaginalis and Prevotella spp. increased significantly. This shift towards dysbiosis is statistically significant and underscores the impact of menopause on vaginal health.24,25 The statistical analysis of the results revealed notable variations separating the two groups in terms of Lactobacillus abundance and pathogenic bacterial load. The reduction in Lactobacillus species and the increase in pathogenic bacteria were both statistically significant, supporting the hypothesis that hormonal changes during menopause contribute to microbial imbalance and increased susceptibility to infections.26,27

In conclusion, the findings of this study clearly demonstrate that menopause significantly alters the vaginal microbiota, leading to a depletion of helpful Lactobacillus species and pathogenic bacterial overgrowth. This dysbiotic state elevates the vaginal pH and increases the risk of infections like bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis. The decline in estrogen levels during menopause seems to be really important in this microbial shift by reducing glycogen levels in the vaginal epithelium, thereby limiting nutrients for Lactobacillus growth. The findings highlight the necessity of implementing targeted therapies, like probiotic supplements or hormone replacement therapy, to re-establish microbial equilibrium and enhance vaginal health in postmenopausal women. The ramifications of these findings are substantial, as they underscore the necessity for healthcare practitioners to recognise the alterations in vaginal microbiota linked to menopause and to devise suitable methods for managing the health of postmenopausal women. Future research should concentrate on examining the effectiveness of several therapies designed to restore a healthy vaginal microbiome and reduce the risks linked to dysbiosis in this demographic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their heartfelt gratitude to Vinayaka Mission’s Medical College, Karaikal, and the Vinayaka Mission Research Foundation for their continuous support and for providing the necessary facilities and funding to carry out this research. The authors also extend their appreciation to all the participants and staff involved in the study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

NS conceptualized the study, applied methodology and performed data collection. JB performed literature review, data analysis, Interpretation. MS performed microbiological analysis. SK performed supervision and project administration. NS wrote the manuscript. SK reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

This study was supported by the Vinayaka Mission Research Foundation under the Seed Money Grant Program. Unique Project ID: VMRF/Research/Seed Money/April 2021/2.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Vinayaka Mission’s Medical College, Karaikal, India, vide approval number VMMC/2022/JUL/78.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- Li J, McCormick J, Bocking A, Reid G. Importance of vaginal microbes in reproductive health. Reprod Sci. 2012;19(3):235-242.

Crossref - Shen L, Zhang W, Yuan Y, Zhu W, Shang A. Vaginal microecological characteristics of women in different physiological and pathological period. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:959793.

Crossref - Gupta S, Kakkar V, Bhushan I. Crosstalk between vaginal microbiome and female health: a review. Microb pathog. 2019;136:103696.

Crossref - Heravi FS. Host-vaginal microbiota interaction: shaping the vaginal microenvironment and bacterial vaginosis. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep. 2024;11(3):177-191.

Crossref - Giraldo HP, Giraldo PC, Mira TA, et al. Vaginal microbiome of women with premature ovarian insufficiency: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Climacteric. 2024;27(6):542-547.

Crossref - Hanson L, VandeVusse L, Jerme M, Abad CL, Safdar N. Probiotics for treatment and prevention of urogenital infections in women: a systematic review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61(3):339-55.

Crossref - Sonnex C. Sexual Health and Genital Medicine in Clinical Practice. Springer. 2015.

Crossref - Al-Badaii F, Al-Tairi M, Rashid A, Al-Morisi S, Al-Hamari N. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Urinary Tract Infections among Pregnant Women: A Study in Damt District Yemen. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2023;17(2):1065-1075.

Crossref - Kohlerschmidt DJ, Mingle LA, Dumas NB, Nattanmai G. Identification of aerobic Gram-negative bacteria. In: Green LH, Goldman E, 4th eds. Practical Handbook of Microbiology. 2021:59-70.

Crossref - Geelen TH, Rossen JW, Beerens AM, et al. Performance of cobas® 4800 and m2000 real-time™ assays for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in rectal and self-collected vaginal specimen. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;77(2):101-105.

Crossref - Gandhi K, Gutierrez P, Garza J, Arispe R, Galloway M, Ventolini G. Lactobacillus species and inflammatory cytokine profile in the vaginal milieu of pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women. GREM—Gynecol. Reprod. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;1:180-7.

- Balashov SV, Mordechai E, Adelson ME, Sobel JD, Gygax SE. Multiplex quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay for the identification and quantitation of major vaginal lactobacilli. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78(4):321-327.

Crossref - Petrova MI, Lievens E, Malik S, Imholz N, Lebeer S. Lactobacillus species as biomarkers and agents that can promote various aspects of vaginal health. Front Physiol. 2015;6:81.

Crossref - Siddiqui R, Makhlouf Z, Alharbi AM, Alfahemi H, Khan NA. The gut microbiome and female health. Biology. 2022;11(11):1683.

Crossref - Amabebe E, Anumba DOC. The vaginal microenvironment: the physiologic role of lactobacilli. Front Med. 2018;5:181.

Crossref - Qi W, Li H, Wang C, Li H, Fan A, Han C, Xue F. The effect of pathophysiological changes in the vaginal milieu on the signs and symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Menopause. 2021;28(1):102-8.

Crossref - Brown AMC, Gervais NJ. Role of ovarian hormones in the modulation of sleep in females across the adult lifespan. Endocrinology. 2020;161(9):bqaa128.

Crossref - Van Gerwen OT, Smith SE, Muzny CA. Bacterial vaginosis in postmenopausal women. Current infectious disease reports. 2023;25(1):7-15.

Crossref - Zhang X, Zhong H, Li Y, et al. Sex-and age-related trajectories of the adult human gut microbiota shared across populations of different ethnicities. Nat Aging. 2021;1(1):87-100.

Crossref - Hong L, Liang H, Man W, Zhao Y, Guo P. Estrogen and bacterial infection. Frontiers in Immunology. 2025;16:1556683.

Crossref - Harding AT, Heaton NS. The impact of estrogens and their receptors on immunity and inflammation during infection. Cancers. 2022;14(4):909.

Crossref - Chee WJ, Chew SY, Than LT. Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microbial cell factories. 2020;19(1):203.

Crossref - Lewis AL, Gilbert NM. Roles of the vagina and the vaginal microbiota in urinary tract infection: evidence from clinical correlations and experimental models. GMS infectious diseases. 2020;8:Doc02.

Crossref - Mitchell CM, Ma N, Mitchell AJ, et al. Association between postmenopausal vulvovaginal discomfort, vaginal microbiota, and mucosal inflammation. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2021;225(2):159-e1.

Crossref - Nieto MR, Rus MJ, Areal-Quecuty V, Lubián-López DM, Simon-Soro A. Menopausal shift on women’s health and microbial niches. npj Women’s Health. 2025;3(1):3.

Crossref - Lin F, Ma L, Sheng Z. Health disorders in menopausal women: microbiome alterations, associated problems, and possible treatments. BioMedical Engineering OnLine. 2025;24(1):84.

Crossref - Hong L, Liang H, Man W, Zhao Y, Guo P. Estrogen and bacterial infection. Frontiers in Immunology. 2025;16:1556683

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.