ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Observational studies regarding the correlation between colorectal carcinoma, inflammatory bowel disease and Helicobacter pylori infection are inconsistent. The present study aims to investigate the association between colorectal adenocarcinoma (CRA) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with H. pylori status in 100 patients who have inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal carcinoma was confirmed disease by histological approach. Besides, a meta-analysis was performed of published studies, to evaluate the link between H. pylori infection and an increased risk of CRC and IBD. Among 67 cases with CRA and 33 cases with IBD, 59.7% and 51.5% were H. pylori positive; respectively. In the meta-analysis, thirty-nine articles were included, involving 13 231 cases with CRC and 2477 with IBD. The pooled odds ratio for CRC and IBD was 1.16 (95%CI = 0.73-1.82) and 0.42 (95%CI = 0.32-0.56); respectively. Our meta-analysis indicates that H. pylori is not associated with CRC.

Colorectal adenocarcinoma, colorectal cancer, Helicobacter pylori, IBD, immunohistochemistry, meta-analysis

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is the third most diagnosed cancer and the second most lethal cancer worldwide.1,2 In Morocco, colorectal cancer is classified as the first digestive cancer and remains a burden in the country, as 2484 new cases are diagnosed and account for ~14.8% of deaths annually.4,5 Additionally, it´s well known that colorectal cancer is sporadic. However, genetic and environmental risk factors are regarded as the most important.6,7 Furthermore, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) related to Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC); were associated positively with the occurrence of CRC.8-10

Despite the long-standing associations between bacterial infection and carcinogenesis, researchers have recently highlighted, the implication of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in the initiation of colorectal carcinogenesis and the progression of CRC.11 H. pylori is a well-known cause of gastroduodenal disease.12 Beside gastric cancer, H. pylori infection has been correlated with other digestive tract cancers such as CRC.13 However, the cause and effect relationship of H. pylori with colorectal carcinogenesis, is still under debate; several studies have detected Helicobacter spp. in IBD, colonic adenoma and colonic adenocarcinoma.14-19 Nevertheless, the results were conflicting. In Morocco, there is no study linking H. pylori to colorectal adenocarcinoma and IBD.

To better evaluate the association of H. pylori infection with the risk of developing colorectal cancer, we aim to detect the presence of H. pylori in cases with IBD and colorectal adenocarcinomas (CRA).20 We also aim to update and review systematically current information regarding H. pylori in CRC and IBD.

Histological study

It is a prospective study, conducted at the department of pathological anatomy in Mohammed VI University Hospital Center in Marrakech. The biopsies were obtained by colonoscopy in the gastroenterology department in the University Hospital Center of Marrakech and examined histopathologically at the anatomy-pathology department in the Arrazi hospital CHU Mohammed VI in Marrakech. This study included 100 cases (67 colorectal adenocarcinoma, 23 ulcerative colitis and 10 Crohn’s disease cases) over 2 years (May 2018-May 2020). Medical and pathology records of the included cases were retrieved. The histopathological aspect of the study was performed by pathologists in accordance with the World Health Organisation (WHO) pathology and genetics (2010). After formalin fixation and paraffin embedding, the samples were sectioned and stained with Hematoxylin and eosine (H&E), and then analyzed by optical microscopy. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of the Marrakech University Hospital Center. Patient consent was signed before the colonoscopy. In the case of illiterate or semi-illiterate consenters the written consent was explained by the investigator.

Data such as: sex, age, macroscopic aspect, anatomical location, degree of infiltration, histological type and degree of tumor differentiation were collected prospectively from the medical records of the included cases.

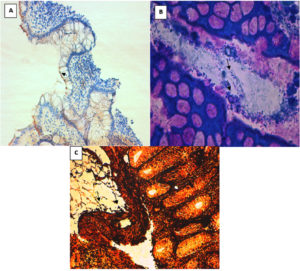

The detection for Helicobacter pylori was performed by histological Stains: modified Giemsa, Warthin-Starry and immunohistochemical staining were used to detect Helicobacter pylori, as previously described.13,21

The statistical analysis was performed using the software SPSS v26. The ҳ2 test was used to evaluate the association between the presence of H. pylori and the variable collected, p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Meta-analysis

Literature search

We followed PRISMA guidelines to conduct the meta-analysis. A systematic search was conducted from 1998 to 2019 using EMBASE, Web of Science, PubMed, and Cochrane Database. Two researchers (S.C and K.E) conducted literature searches independently, using the following terms: “H. pylori” or “Helicobacter pylori” and “Inflammatory bowel disease” or” IBD” or “Colorectal cancer” or “CRC” or “Crohn disease” or “ulcerative colitis” or “colitis”.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: i) observational studies including case-control studies, ii) detection of H. pylori by PCR, fast urease test, immunohistochemistry, specific staining (Giemsa and Warthin Starry) and ELISA, and iii) studies limited to humans.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted: I) the first author’s name, ii) the year of publication, iii) the study design, iv) the country where the study was conducted, v) the method used to detect H. pylori, vi) diagnosis; and vii) sample size.

Statistical analysis

Calculations were carried out by generating odds ratio “OR” with their 95% CIs using a random-effects model. Assessment of heterogeneity was performed using the Chi-square test and the I2statistic. If I2 statistic value is >50%, then the level of heterogeneity is considered as high.

Publication bias detection was performed by using Begg’s rank correlation test and Egger’s test. A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the software Rstudio version 1.3.1093 (USA).

As shown in Table 1, the median age of patients with IBD is 29.99±8.77 years, and that of patients with adenocarcinomas is 64.5 ±15.933 years. The male to female ratios for IBD and CRA were 0.73:1 and 1.31:1, respectively. In the CRA group, the tumour is frequently located in the left colon and the rectum (40.3% each), while 19.4% of tumours are located in the right colon. Macroscopically, in the CRA group, ulcerative-burgeoning tumours were the most common type (86.5%). The Lieberkuhnian adenocarcinoma was the most common histologic type (98.5%), followed by Mucinous CRA (1.5%). And according to the degree of tumour differentiation, 74.6% of adenocarcinomas are moderately differentiated, 19.4% are poorly differentiated and 5.9% are well differentiated. Depending on the degree of locoregional invasion, 97% of adenocarcinomas are infiltrated into the sub-serosa followed by 1.5% that is infiltrated into the serosa.

Table (1):

Clinical and histopathological characteristics of patients with CRA and IBD (N= 100).

| Categories | Variables | CRA (N=67) | IBD (N=33) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female (48/100) | 29 (43%) | 19 (57,57%) |

| Male (52/100) | 38 (57%) | 14 (42,42%) | |

| Age (median) | 64,5 ±15,933 | 29,99±8,77 | |

| Anatomical localisation of the disease | Right colon | 13 (19,4%) | 10 (30,30%) |

| Left colon | 27 (40,3%) | 15 (45,46%) | |

| Rectum | 27 (40,3%) | 8 (24,24%) | |

| Macroscopic aspect of CRA | bourgeoning | 9 (15.5%) | – |

| ulcero-bourgeoning | 58 (86,5%) | – | |

| Histological types of CRA | Lieberkuhnien ACR | 66 (98,5%) | – |

| Mucinous ACR | 1 (1,5%) | – | |

| Degree of differentiation | Well-differentiated | 4 (5.9%) | – |

| Moderately differentiated | 50 (74.6%) | – | |

| Poorly differentiated | 13 (19.4%) | – | |

| Infiltration of CRA | Infiltrating the muscularis | 1 (1.5%) | – |

| Infiltrating the serosal surface | 1 (1.5%) | – | |

| Infiltrating the subserosal | 65 (97%) | – | |

CRA: colorectal adenocarcinoma, IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease

Special stainings and the immunohistochemistry revealed that H. pylori was present in 59.7% of CRA and 51.5% of IBD (Fig. 1, Table 2). 41.3% of women with CRA were H. pylori positive vs 73.6% of men (p≤0.05). Also, a positive association was found between H. pylori presence and the anatomical location of the diseases and the macroscopic aspect of the tumour. No association was found between H. pylori positivity and age, histological type, degree of differentiation and infiltration of the tumour (Table 2).

Table (2):

Characteristics of the patients linked with H. pylori infection (N=100) Chi square (χ2) test

| Categories | Variables | H. pylori positive n (%) | H. pylori negative n (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | IBD | Female | 12 (36.36%) | 5 (15.15%) | 0.16 |

| Male | 7 (21.21%) | 9 (27.27%) | |||

| CRA | Female | 12 (17.91%) | 17 (25.37%) | 0.01 | |

| Male | 28 (41.79%) | 10 (14.92%) | |||

| Age | IBD | A<50 | 15 (45.45%) | 11 (33.33%) | 0.67 |

| A≥51 | 5 (15.15%) | 2 (6.06%) | |||

| CRA | A<50 | 7 (10.44%) | 33 (49.25%) | 0.001 | |

| A≥51 | 15 (22.38%) | 12 (17.91%) | |||

| Anatomical location of IBD | Right colon | 4 (12.12%) | 6 (18.18%) | 0.36 | |

| Left colon | 7 (21.21%) | 8 (24.24%) | |||

| Rectum | 6 (18.18%) | 2 (6.06%) | |||

| Anatomical location of CRA | Right colon | 4 (5.97%) | 9 (13.43%) | 0.0007 | |

| Left colon | 23 (34.32%) | 4 (5.97%) | |||

| Rectum | 13 (19.4%) | 14 (20.89%) | |||

| Macroscopic aspect of CRA | Bourgeoning | 3 (4.47%) | 6 (8.95%) | 0.015 | |

| ulcero-bourgeoning | 37 (55.22%) | 11 (16.42%) | |||

| Histological types of CRA | Lieberkuhnian | 40 (59.7%) | 26 (38.8%) | 0.40 | |

| Mucinos | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.49%) | |||

| Differentiation | Well differentiated | 2 (2.98%) | 2 (2.98%) | 0.68 | |

| Moderately differentiated | 28 (41.79%) | 22 (32.83%) | |||

| Poorly differentiated | 10 (14.92%) | 13 (19.4%) | |||

Fig. 1. Detection of Helicobacter pylori by histological staining techniques: (A) by immunohistochemistry (× 100) B) Giemsa (× 1000) and (C) by Warthin starry (× 1000).

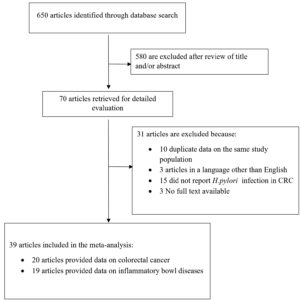

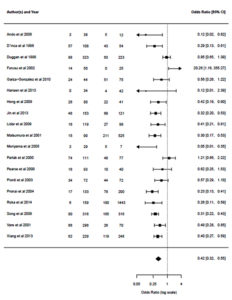

For the meta-analysis, a flow chart of study selection is reported in Fig. 2. The initial search identified 650 articles. Of these, 39 articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were retrieved for detailed evaluation. Twenty of these studies included 13231 patients with CRC, while nineteen articles were about 2477 patients with IBD.

In the included articles (Table 3), 22 were performed in Europe, 12 in Asia, 3 in America and two in Turkey. In terms of H. pylori detection methods, 24 studies used serological tests (ELISA), 8 used C-urea breath tests, 8 performed histological techniques (IHC, special staining), 3 used H. pylori culture used PCR. A combination of 2 to 3 detection techniques was used in 3 studies.

Table (3):

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Study |

Country |

Detection methods |

Type of malignancy |

Positivity in cases group(n/N) |

Positivity in control group(n/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Wang et al22 |

China |

histology |

CRC |

189/3044 |

890/2362 |

Butt et al23 |

USA |

serology |

CRC |

1665/4063 |

1625/4063 |

Blase et al24 |

Gemany |

serology |

CRC |

213/392 |

121/774 |

Zhang et al25 |

China |

serology |

CRC |

265/569 |

205/569 |

Roka et al26 |

Greece |

Histology+ culture+ UBT |

IBD |

2/34 UC 3/66 CD 1/ 59 unspecified |

190/1443 |

Hansen et al27 |

Scotland |

histology |

IBD |

0/29 CD 0/13 UC 0/2 unspecified |

4/42 |

Jin et al28 |

China |

UBT+culture |

UC |

46/153 |

69/121 |

Nam et al29 |

Korea |

serology |

CRC |

6/9 |

248/470 |

Xiang et al30 |

China |

UBT +culture |

CD |

62/229 |

119/248 |

Zhang et al31 |

Germany |

serology |

CRC |

790/1712 |

669/1669 |

Strofilas et al32 |

Greece |

serology |

CRC |

66/93 |

13/20 |

Engin et al33 |

Turkey |

serology |

CRC |

77/110 |

71/116 |

Garza-Gonzalez et al34 |

Mexico |

serology |

IBD |

12/23 UC 12/21 CD |

51/75 |

Hong et al35 |

Korea |

histology |

IBD |

26/80 |

22/41 |

Lidar et al36 |

Italy |

serology |

IBD |

11/80 CD 5/39 UC |

27/98 |

Song et al37 |

Korea |

UBT |

IBD |

54/169 UC 26/147 CD |

165/316 |

Ando et al38 |

Japan |

UBT |

CD |

3/38 |

5/12 |

Bulajic et al39 |

Serbia |

PCR (ureA) |

CRC |

1/83 |

5/40 |

D’Onghia et al40 |

Italy |

serology |

CRC |

13/29 |

19/50 |

Jones et al41 |

UK |

histology |

CRC |

10/59 |

1/58 |

Montani et al42 |

Japan |

serology |

CRC |

74/113 |

145/226 |

Zumkeller et al43 |

Germany |

serology |

CRC |

195/384 |

204/467 |

Georgopoulos et al44 |

Greece |

serology |

CRC |

62/78 |

53/78 |

Moriyama et al45 |

Japan |

UBT |

CD |

3/29 |

5/7 |

Pronai et al46 |

Hungary |

UBT |

IBD |

10/82 UC 7/51 CD |

78/200 |

Piodi et al47 |

Italy |

UBT |

IBD |

17/32 CD 17/40 UC |

44/72 |

Limburg et al48 |

Finland |

serology |

CRC |

89/118 |

184/236 |

Furusu et al49 |

Japan |

Serology+ histology |

IBD |

0/25 UC 14/25 CD |

0/25 |

Siddheshwar et al50 |

Uk |

serology |

CRC |

110/189 |

110/179 |

Matsumura et al51 |

Japan |

serology |

CD |

15/90 |

211/525 |

Hartwick et al17 |

Poland |

serology |

CRC |

34/40 |

96/160 |

Vare et al52 |

Finland |

serology |

IBD |

55/185 UC 8/94 CD 3/17 Unspecified |

26/70 |

Parlak et al53 |

Turkey |

histology |

IBD |

46/66 UC 28/45 CD |

48/77 |

Pearce et al54 |

England |

Serology+UBT |

IBD |

11/51 UC 5/42 CD |

10/40 |

Breuer-Katschinski et al18 |

Germany |

serology |

CRC |

62/98 |

55/98 |

Thorburn et al55 |

USA |

serology |

CRC |

159/233 |

158/233 |

D´inca et al56 |

Italy |

histology |

IBD |

25/41 UC 33/67 CD |

54/43 |

Duggan et al57 |

England |

serology |

IBD |

59/213 UC 29/110 CD |

63/223 |

CRC: colorectalcancer, IBD: Inflammatory bowl disease, CD: Crohn s disease, UC: ulcerative colitis, UBT: 13C urease breath test, PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction

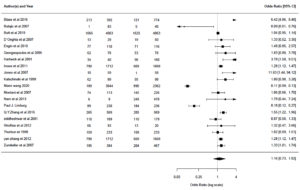

The overall meta-analysis revealed no significant association between H. pylori and CRC (OR 1.16, 95%CI 0.73 to 1.82, p-value 0.74), and a negative association was found between H. pylori and IBD (OR 0.42, 95 % CI 0.32 to 0.56, p-value ≤0.0001) (Fig. 3, 4). However, heterogeneity was observed (p < 0.0001, I2 = 95%) (p < 0.0001, I2 = 69%) in CRC and IBD; respectively. As shown in Fig. 5, the funnel plots of publication bias appears asymmetric. Thus, we can assume the possibility of publication bias.

CRC accounts for 8% of cancer deaths worldwide.4 This malignancy is asymptomatic until it reaches an advanced stage.58 Nowadays, it is known that IBD has a high relationship with CRC.59 The pathogenesis of CRC and IBD is still under debate. However, several pathways, have been proposed including TNF-α activation, which activates the transcription factor NF-kB. Besides, IL6 might also activate signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT), followed by the activation of JAKs (Janus kinase).5,59-61

Brackmann et al.,18 mentioned that patients with CRC related to IBD are affected at a younger age. In our study, the median age of patients with IBD was 29 years old. Besides, the median age in patients with CRC was 64.5 years in the present study. A comparable result was reported in a retrospective study conducted in Rabat.4

CRC is influenced by sex and gender, with males having significantly higher mortality rates.60,61 This might be due to several behavioural and gender-related factors such as a diet with red meat, alcohol consumption, and smoking. In our study, 57% of the cases were male.

Depending on the CRC anatomical position, the disease progression and the overall survival of CRCs will differ. The difference between these tumours is due to different cancerogenic factors and to the developmental origin of the tumour.62 Besides, a slight decrease in the incidence of the right-sided CRC was observed worldwide That can be explained by the progress of diagnostic, treatment and by the prevention of these cancers by ablation of the adenomatous polyps in the right part of the colon. An increase was reported in the left colon CRC.9 In a study conducted in Morocco, 60.3% of tumours were located in the rectum, 23.2% were located in the left colon, and 16.5% of tumours were located in the right colon.63 In our study, 19.4% of tumours are right-sided, 40.3% are left-sided and 40% are located in the rectum.

Regarding a probable correlation between colorectal carcinoma and H. pylori infection, several mechanisms have been proposed; such as the increasing release of gastrin that acts as a mitogen, the changing of gut microbiota and IBD induced during the migration of H. pylori from the mucosa to the light of the colon by faecal excretions.11,64,65 Besides, H. pylori virulence factors, like Cag A and Vac A that are associated with gastric adenocarcinoma, might have the same effect on CRC.66

In addition, an in-vitro study demonstrated that H. pylori lipopolysaccharides, can intervene with the DNA repair system of the colonic epithelial cells, promoting genotoxicity and then colon carcinogenesis.67 Also, it was shown that H. pylori lipopolysaccharides induce the production of nitric oxide, by inhibition of DNA repair enzymes and pro-apoptotic effector proteins resulting from the nitrosylation of their tyrosine and cysteine residues, causing chronic inflammation and then cancer.68,69

Several epidemiological studies have associated H. pylori infection with CRC and precancerous lesions like IBD, while others failed to establish a statistical association.11,70 Therefore, a quantitative evaluation of a possible association between CRC, IBD and H. pylori is required. In the current meta-analysis, 39 studies, with 13231 CRC cases and 2477 IBD cases, fit the selection criteria. The overall analyses showed no significant association between H. pylori and CRC (OR 1.16, 95%CI 0.73 to 1.82, p-value 0.74), and a negative association between H. pylori and IBD (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.56, p-value ≤0.0001). Moreover, in the present prospective study, no correlation between H. pylori and IBD was addressed. Consistently, this study has shown a negative association between H. pylori and IBD The mechanism of the protective effect is the production of IL-18 by the suppressive T cells.71 Another immunoregulatory mechanism has been proposed involving the production of H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein, that decreases inflammation by agonist ligation of toll-like receptor 2, and H. pylori DNA, that averts sodium dextran sulfate-included colitis in mice.72

However, an association was found between sex, age, anatomical location, macroscopic aspect of the tumour in CRA patients and H. pylori (P≤0.05). These findings, plus the fact that very few studies have used PCR and histology to identify H. pylori in colorectal tissues, lead to the necessity to use more sensitive techniques to detect H. pylori in CRC subjects.

Our study presented had several limitations. First, several studies included in our meta-analysis used serological tests that can’t distinguish the exact location of H. pylori. Second, few have reported the exclusion of patients who have been administrated an H. pylori eradication treatment. Third, significant heterogeneity was found across studies, which might be explained by the geographic distribution and detection methods used.73,74

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that assesses the association between IBD and CRC with H. pylori infection in Morocco. Our results assert a possible association between H. pylori and sex, age, anatomical location and macroscopic aspect of the tumour in CRA patients. In the present meta-analysis, no association between H. pylori and CRC was established. Moreover, a negative association between H. pylori and IBD was addressed. However, more studies are needed to investigate the association of H. pylori with CRC risk using molecular techniques.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

SC and KB conceptualize and designed the study. KB, SC, SS, MD, KK, MEM, SE, AA and HR collected, generated, assembled, analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was apporved by the Ethics Committees of the Arrazi Hospital CHU Mohammed VI of Marrakech, Morocco.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA

Not applicable.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424.

Crossref - Prashanth R, Tagore S, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factor. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14(2):89-103.

Crossref - Chbani L, Hafid I, Berraho M, Nejjari C, Amarti A. Digestive cancers in Morocco: Fez-Boulemane region. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13:46.

- Haimer A, Belamalem S, Habib F, Soulaymani A, Abdelrhani M, Hami H. Colorectal Cancer in Morocco: Results of a Retrospec-tive Study. Biosciences, Biotechnology Research Asia. 2019;16:79-83.

Crossref - Haggar FA, Boushey RP. Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Risk Factors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22(4):191-197.

Crossref - Drewes JL, Housseau F, Sears CL. Sporadic colorectal cancer: microbial contributors to disease prevention, development and therapy. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(3):273-280.

Crossref - Hope ME, Hold GL, Kain R, El-Omar EM. Sporadic colorectal cancer-role of the commensal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;244(1):1-7.

Crossref - Wang ZH, Fang JY. Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Surveillance. Gastrointest Tumors. 2014;1(3):146-154.

Crossref - Kim ER, Chang DK. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: the risk, pathogenesis, prevention and diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(29):9872-9881.

Crossref - Brand MI, Church JM. High Risk Premalignant Colorectal Conditions. Surgical Oncology. 2003;346-363.

Crossref - Butt J, Epplein M. Helicobacter pylori and colorectal cancer-A bacterium going abroad? PLOS Pathogens. 2019;15(8):e1007861.

Crossref - Cherif S, Bouriat K, Rais H, Elantri S, Amine A. Helicobacter pylori and Biliary Tract Cancers: A Meta-Analysis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2020;2020:9287157.

Crossref - Cherif S, Rais H, Hakmaoui A, Sellami S, Elantri S, Amine A. Linking Helicobacter pylori with gallbladder and biliary tract cancer in Moroccan population using clinical and pathological profiles. Bioinformation. 2019;15(10):735-743.

Crossref - Tatishchev SF, Vanbeek C, Wang HL. Helicobacter pylori infection and colorectal carcinoma: is there a causal association? J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3(4):380-385.

Crossref - Zumkeller N, Brenner H, Zwahlen M, Rothenbacher D. Helicobacter pylori Infection and Colorectal Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Helicobacter. 2006;11(2):75-80.

Crossref - Meucci G, Tatarella M, Vecchi M, et al. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in pa-tients with colonic adenomas and carcinomas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25(4):605-607.

Crossref - Hartwich J, Konturek SJ, Pierzchalski P, et al. Molecular basis of colorectal cancer – role of gastrin and cyclooxygenase-2. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7(6):1171-1181.

- Breuer-Katschinski B, Nemes K, Marr A, et al. Helicobacter pylori and the risk of colonic adenomas. Colorectal Adenoma Study Group. Digestion. 1999;60(3):210-215.

Crossref - Butt J, Jenab M, Pawlita M, et al. Antibody responses to Helicobacter Pylori and risk developping colorectal cancer in a European cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Preven. 2020;29(7):1475-1481.

Crossref - Pronai L, Schandl L, Orosz Z, Magyar P, Tulassay Z. Lower Prevalence of Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease- Antibiotic Use in The History Does Not Play a Significant Role. Helicobacter. 2004;9(3):278-283.

Crossref - Farouk WI, Hassan NH, Ismail TR, Daud IS, Mohammed F. Warthin-Starry Staining for the Detection of Helicobacter pylori in Gastric Biopsies. Malays J Med Sci. 2018;25(4):92-99.

Crossref - Wang M, Kong W-J, Zhang J-Z, et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with colorectal polyps and malignancy in China. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;12(5):582-591.

Crossref - Butt J, Varga MG, Blot WJ, et al. Serologic Response to Helicobacter pylori Proteins Associated With Risk of Colorectal Cancer Among Diverse Populations in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):175-186.e2.

Crossref - Blase JL, Campbell PT, Gapstur SM, et al. Prediagnostic Helicobacter pylori Antibodies and Colorectal Cancer Risk in an Elderly, Caucasian Population. Helicobacter. 2016;21(6):488-492.

Crossref - Zhang Q-Y, Lv Z, Sun L-P, Dong N-N, Xing C-Z, Yuan Y. Clinical significance of serum markers reflecting gastric function and H. pylori infection in colorectal cancer. J Cancer. 2019;10(10):2229-2236.

Crossref - Roka K, Roubani A, Stefanaki K, Panayotou I, Roma E, Chouliaras G. The Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Gastritis in Newly Diagnosed Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Helicobacter. 2014;19(5):400-405.

Crossref - Hansen R, Berry SH, Mukhopadhya I, et al. The Microaerophilic Microbiota of De-Novo Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The BISCUIT Study. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58825.

Crossref - Jin X, Chen Y-P, Chen S-H, Xiang Z. Association between Helicobacter Pylori infection and ulcerative colitis-a case control study from China. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(11):1479-1484.

Crossref - Nam KW, Baeg MK, Kwon JH, et al. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity is positively associated with colorectal neoplasms. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2013;61(5):259-264.

Crossref - Xiang Z, Chen Y-P, Ye Y-F, et al. Helicobacter pylori and Crohn’s disease: a retrospective single-center study from China. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(28):4576-4581.

Crossref - Zhang Y, Hoffmeister M, Weck MN, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori Infection and Colorectal Cancer Risk: Evidence From a Large Population-based Case-Control Study in Germany. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;175(5):441-450.

Crossref - Strofilas A, Lagoudianakis EE, Seretis C, et al. Association of helicobacter pylori infection and colon cancer. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4(3):172-176.

Crossref - Engin AB, Karahalil B, Engin A, Karakaya AE. Oxidative Stress, Helicobacter pylori, and OGG1 Ser326Cys, XPC Lys939Gln, and XPD Lys751Gln Polymorphisms in a Turkish Population with Colorectal Carcinoma. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. 2010;14(4):559-564.

Crossref - Garza-Gonzalez E, Perez-Perez GI, Mendoza-Ibarra SI, Flores JP-Gutierrez, Bosques-Padilla FJ. Genetic risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease in a North-eastern Mexican population. Int J Immunogenet. 2010;37(5):355-359.

Crossref - Hong CH, Park DI, Choi WH, et al. The clinical usefulness of focally enhanced gastritis in Korean patients with Crohn’s disease. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53(1):23-28.

- Lidar M, Langevitz P, Barzilai O, et al. Infectious Serologies and Autoantibodies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173(1):640-348.

Crossref - Song MJ, Park DI, Hwang SJ, et al. The Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Korean Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease, a Multicenter Study. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53(6):341-347.

Crossref - Ando T, Watanabe O, Ishiguro K, et al. Relationships between Helicobacter pylori infection status, endoscopic, histopathological findings, and cytokine production in the duodenum of Crohn’s disease patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(s2):S193-S197.

Crossref - Bulajic M, Stimec B, Ille T, et al. PCR detection of helicobacter pylori genome in colonic mucosa: normal and malignant. Prilozi. 2007;28(2):25-38.

- D’Onghia V, Leoncini R, Carli R, et al. Circulating gastrin and ghrelin levels in patients with colorectal cancer: Correlation with tumour stage, Helicobacter pylori infection and BMI. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;61(2):137-141.

Crossref - Jones M, Helliwell P, Pritchard C, Tharakan J, Mathew J. Helicobacter pylori in colorectal neoplasms: is there an aetiological relationship? 2007;5:51-.

Crossref - Machida-Montani A, Sasazuki S, Inoue M, et al. Atrophic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori, and colorectal cancer risk: a case-control study. Helicobacter. 2007;12(4):328-332

Crossref - Zumkeller N, Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Hoffmeister M, Nieters A, Rothenbacher D. Helicobacter pylori infection, interleukin-1 gene polymorphisms and the risk of colorectal cancer: Evidence from a case-control study in Germany. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(8):1283-1289.

Crossref - Georgopoulos SD, Polymeros D, Triantafyllou K, et al. Hypergastrinemia is associated with increased risk of distal colon adenomas. Digestion. 2006;74(1):42-46.

Crossref - Moriyama T, Matsumoto T, Jo Y, et al. Mucosal proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine ex-pression of gastroduodenal lesions in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(s2):85-91.

Crossref - Pronai L, Schandl L, Orosz Z, Magyar P, Tulassay Z. Lower Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease But Not With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease – Antibiotic Use in the History Does Not Play a Significant Role. Helicobacter. 2004;9(3):278-283.

Crossref - Piodi LP, Bardella M, Rocchia C, Cesana BM, Baldassarri A, Quatrini M. Possible Protective Effect of 5-Aminosalicylic Acid on Helicobacter pylori Infection in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36(1):22-25.

Crossref - Limburg PJ, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Colbert LH, et al. Helicobacter Pylori Seropositivity and Colorectal Cancer Risk. A Prospective Study of Male Smokers. 2002;11(10):1095-1099.

- Furusu H, Murase K, Nishida Y, et al. Accumulation of mast cells and macrophages in focal active gastritis of patients with Crohn’s disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49(45):639-643.

- Siddheshwar RK, Muhammad KB, Gray JC, Kelly SB. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter Pylori in Patients With Colorectal Polyps and Colorectal Carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(1):84-88.

Crossref - Matsumura M, Matsui T, Hatakeyama S, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and correlation between severity of upper gastrointestinal lesions and H. pylori infection in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(11):740-747.

Crossref - Vare PO, Heikius B, Silvennoinen JA, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Is Helicobacter pylori Infection a Protective Factor? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(12):1295-1300.

Crossref - Parlak E, Ulker A, Disibeyaz S, Alkim C, Dagli U. There Is No Significant Increase in the Incidence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Turkey. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33(1):87-88.

Crossref - Pearce CB, Duncan HD, Timmis L, Green JR. Assessment of the prevalence of infection with Helicobacter pylori in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12(4):439-443.

Crossref - Thorburn CM, Friedman GD, Dickinson CJ, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Parsonnet J. Gastrin and colorectal cancer: A prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(2):275-280.

Crossref - D’Inca R, Sturniolo G, Cassaro M, et al. Prevalence of Upper Gastrointestinal Lesions and Helicobacter pylori Infection in Crohn’s Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(5):988-992.

Crossref - Duggan AE, Usmani I, Neal KR, Logan RFA. Appendicectomy, childhood hygiene, Helicobacter pylori status, and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a case control study. Gut. 1998;43(4):494-498.

Crossref - Kuipers EJ, Grady WM, Lieberman D, et al. Colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1(1):15065.

Crossref - Hnatyszyn A, Hryhorowicz S, Kaczmarek-Rys M, et al. Colorectal carcinoma in the course of inflammatory bowel diseases. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2019;17:18.

Crossref - Stidham RW, Higgins PDR. Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31(3):168-178.

Crossref - Dyson JK, Rutter MD. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: what is the real magnitude of the risk? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(29):3839-3848.

Crossref - Baran B, Ozupek NM, Tetik NY, Acar E, Bekcioglu O, Baskin Y. Difference Between Left-Sided and Right-Sided Colorectal Cancer: A Focused Review of Literature. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11(4):264-273.

Crossref - Allali I, Chaqsare S, Boukhatem N et al. A Moroccan Colorectal Cancer Database. 2017;5(3):10-14. http://www.warse.org/IJBMIeH/static/pdf/file/ijbmieh01532017.pdf

- Raskov H, Burcharth J, Pommergaard HC. Linking Gut Microbiota to Colorectal Cancer. J Cancer. 2017;8(17):3378-3395.

Crossref - Cavallo P, Cianciulli A, Mitolo V, Panaro MA. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Helicobacter modu-lates cellular DNA repair systems in intestinal cells. Clin Exp Med. 2011;11(3):171-179.

Crossref - Ohshima H, Bartsch H. Chronic infections and inflammatory processes as cancer risk factors: possible role of nitric oxide in carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1994;305(2):253-264.

Crossref - Campbell DI, Thomas JE. Helicobacter pylori infection in paeddiatric practice. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2005;90(2):25-30.

Crossref - Diaz P, Valderrama MV, Bravo J, Quest AFG. Helicobacter pylori and Gastric Cancer: Adaptive Cellular Mechanisms Involved in Disease Progression. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:5.

Crossref - Papastergiou V, Karatapanis S, Georgopoulos SD. Helicobacter pylori and colorectal neoplasia: Is there a causal link? World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(2):649-658.

Crossref - Arnold IC, Hitzler I, Muller A. The Immunomodulatory Properties of Helicobacter pylori Confer Protection Against Allergic and Chronic Inflammatory Disorders. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:10.

Crossref - Luther J, Owyang S, Takeuchi T, et al. Helicobacter pylori DNA de-creases pro-inflammatory cytokine production by dendritic cells and attenuates dextran sodium sulphate-induced colitis. Gut. 2011;60(11):1479-1486.

Crossref - Michetti P. Gutjnl. Experimental Helicobacter pylori infection in humans: a multitaced challenge. Gut. 2004;53(9):1220-1221.

Crossref - Choi DS, Seo SI, Shin WG, Park CH. Risk for Colorectal Neoplasia in Patients With Helicobacter pylori Infection: Asystematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology. 2020;11(2):E00127.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2022. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.