ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are commonly prevalent in obstetrics and gynaecology settings and Indian data from this specific patient population are lacking. This retrospective study collected microbiological urine reports from Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department over a period of two years. A total of 5903 urine samples were screened and 383 bacterial isolates were identified using standard microbiological techniques and antimicrobial susceptibility was performed. Of the 383 isolates, 77.02% (295/383) were from OPD patients and 22.97% (88/383) from IPD patients. Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. were the two most common uropathogens, their prevalence being 225/383 (58.7%) and 40/383 (10.4%), respectively. E. coli showed 100% susceptibility to fosfomycin in both OPD (193/193) and IPD (32/32) patients. Klebsiella spp. showed 0% (36/36) and 25% (1/4) susceptibility to nitrofurantoin among OPD and IPD isolates, respectively. Our study emphasizes the importance of microbiological report in UTI caused by Klebsiella spp. prior to nitrofurantoin empirical therapy which is largely ineffective in our geographical settings.

Urinary Tract Infections, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Outpatient Department, Inpatient Department

Urinary tract infections are prevalent in healthcare settings and particularly common in obstetrics and gynaecology patients. UTIs in obstetrics and gynaecology settings are typically associated with Gram-negative bacteria notably Escherichia coli which is frequently implicated in 60%-80% of cases worldwide with similar trends reported in South Asian population.1,2 The recurrent nature of UTIs compounded by hospital-based factors such as catheterization and surgical interventions underscores the need for regular surveillance of pathogen profiles and their antimicrobial susceptibility to optimize treatment protocols.3,4 Infections in obstetrics and gynaecology settings pose unique challenges due to the heightened vulnerability of pregnant and postpartum patients who may experience severe complications if infected with multidrug-resistant organisms. High infection rates in labor and postnatal care wards further emphasize the need for focused infection control and antibiotic stewardship.5 Pathogens such as Klebsiella spp., Staphylococcus saprophyticus and Enterococcus spp. are also critical contributors to UTIs in these patient population with some studies noting an increase in their resistance to broad-spectrum antibiotics thus complicating effective management.6,7

This study aims to analyze bacterial isolates from urine samples collected in an Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department. Our study seeks to provide evidence-based insights by documenting resistance profiles of predominant uropathogens which will help refine treatment protocols and support infection control strategies in high-risk obstetrics and gynaecological settings.

Study Design

This retrospective study was conducted over a period spanning from January 2022 to December 2023 in a tertiary care hospital. Urine sample data from Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department for culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were analysed. Pregnant women with clinical diagnosis of UTI, pregnant females and patients attending the Obstetrics & Gynaecology Department, if microbiologically detected to have asymptomatic bacteriuria during the antenatal check-up.

Sample processing and isolate identification

Samples included midstream clean catch and catheterized patients. Urine routine microscopy and cultures were performed. Cystine lactose electrolyte deficient agar (CLED) were used for growth and visualisation of colony characteristics. Urine cultures yielding growth of up to two bacterial species with colony counts exceeding 105 CFU/mL were classified as significant bacteriuria. Growth of up to two species with colony counts ranging from 103 to 105 CFU/mL was considered probable significant bacteriuria. Cultures demonstrating more than two organisms with counts above 103 cfu/mL were interpreted as mixed bacterial growth (contamination), whereas the isolation of normal urethral flora was regarded as commensal contamination. Isolates with colony counts below 103 cfu/mL were reported as insignificant bacteriuria. Asymptomatic bacteriuria was defined as colony counts yielding bacterial growth of 105 CFU/mL or more of pure isolates. Culture plates were read after 18-24 hours of inoculation and isolated samples were subjected to gram staining and a battery of biochemical tests for identification. Repeat urine samples from the same patient were deduplicated before analysis.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was performed by Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar as per CLSI 2023. The inoculum density was adjusted to match 0.5 McFarland turbidity using HiMedia antibiotic discs (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India).8 Quality control was maintained throughout the procedures using ATCC strains (S. aureus 25923 and E. coli 25922).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and proportions with 95% Clopper–Pearson exact confidence intervals (CIs). For categories with small sample sizes (n < 5), only descriptive statistics (proportions with 95% CIs) were presented, and hypothesis testing was avoided due to low statistical reliability. Given the exploratory nature of the study across multiple organisms and antibiotics, no formal adjustment for multiple comparisons was applied.

5903 urine samples were analyzed from Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department. The majority of samples 4761 (80.65%) were collected from OPD and 1142 (19.34%) samples were sourced from various inpatient units like labour room, gynaecology ward, antenatal care ward, postnatal care ward and gynaecology recovery unit. 383 bacterial isolates were identified within the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department. Of these, 295 (77.02%) bacterial isolates were identified in OPD samples and 88 (22.97%) in IPD samples. The predominant age group was >18 years, accounting for 96.94% and 98.86% of the isolates in the OPD and IPD, respectively (p = 0.465) (Table 1).

Table (1):

Distribution of urine samples in OPD and IPD settings

| Distribution of Samples | Obst & Gynae OPD | Obst & Gynae IPD | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total samples received | 4761 | 1142 | – |

| Total bacterial isolates | 295 (77.02%) | 88 (22.97%) | – |

| Age group | |||

| Infants (<1 year) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | – |

| 1-18 years | 9 (3.05%) | 1 (1.13%) | – |

| >18 years | 286 (96.94%) | 87 (98.86%) | 0.4654 |

Uropathogens

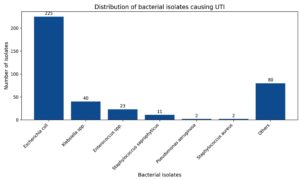

E. coli accounted for 225/383 (58.7%) of all isolates from outpatient and inpatient patients respectively. While Klebsiella spp. accounted for 40/383 (10.4%) from OPD and IPD patients (Figure).

Oral antibiotics like fosfomycin showed susceptibility of 100% to E. coli in both OPD and IPD. Similarly, susceptibility of E. coli to nitrofurantoin showed 100% in OPD and 93.8% in IPD. Ciprofloxacin susceptibility showed 35.5% in OPD and 23.3% in IPD among E. coli isolates. Susceptibility to nitrofurantoin among Klebsiella spp. isolates in OPD and IPD patients were 0% and 25% respectively. Imipenem showed susceptibility of 85.8% in OPD isolate and 0% in IPD from Klebsiella spp. isolates. Among Enterococcus spp. susceptibility to ampicillin was seen in 100% (OPD) and 33.3% (IPD) of isolates. While susceptibility to high level gentamicin were 50% and 25% among OPD and IPD isolates respectively.

Our study provides valuable insight on antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens in obstetrics and gynaecology patients from a northern Indian tertiary care hospital. Despite global concerns about antimicrobial resistance, research on resistance patterns in this specific patient group is limited. Most studies focus on general populations or specific healthcare settings, leaving gaps in understanding resistance trends in obstetrics and gynaecology domain. Our findings will be crucial for developing targeted antimicrobial stewardship strategy and microbiological report based treatment guidelines in our settings. Our susceptibility data for antibiotics like tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are intended solely for surveillance and epidemiological interpretation and are not recommended for clinical use in pregnant patients.

Prevalence of uropathogens

The study identified 383 bacterial isolates from 5903 urine samples from both OPD and inpatients, 295 (77.02%) were isolated from OPD patients and 88 (22.97%) from IPD, with a predominance of Gram-negative bacteria, particularly E. coli. This aligns with previous study in India and Southeast Asia showing E. coli as the most common causative agent of UTI in both outpatient and inpatient settings.9,10

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Gram-negative bacteria

Nitrofurantoin, an oral chemotherapeutic agent, has been used in clinical practice since 1952. It is especially effective against uropathogens due to its broad-spectrum activity.11 Susceptibility to E. coli showed (100% in OPD vs. 93.8% in IPD; p = 0.0289). A slight decline in nitrofurantoin susceptibility among IPD isolates raises concerns about its use in hospitalized settings. Overall, our data is in accordance to national AMR data which showed good susceptibility of 85.8% from urine samples in E. coli isolate.12 Poor susceptibility in Klebsiella spp. was observed (0% in OPD vs. 25% in IPD). The lack of a comparable sample size between OPD and IPD has restricted us to assess the burden of resistance in IPD settings. A similar study based on 5 year retrospective data have demonstrated (6% in OPD vs 5% in IPD).13 Likewise, national AMR surveillance data for Klebsiella spp. in urine showed decreasing pattern susceptibility from 37.6% in 2017 to 36.7% in 2023.12 Although, nitrofurantoin was recommended as a preferred drug in the 2010 international consensus guidelines for urinary tract infections.14 The study shows nitrofurantoin is largely ineffective against Klebsiella spp. and nitrofurantoin-resistant Klebsiella spp. should be suspected when patients fail empirical nitrofurantoin treatment. Our study data suggest avoiding nitrofurantoin as first-line empirical therapy for community-acquired UTIs in pregnant women until culture susceptibility results are available in these geographic settings.

Tetracycline was discovered in the late 1940s from Streptomyces aureofaciens and Streptomyces rimosus and function by blocking protein synthesis.15 In our study, doxycycline susceptibility of E. coli showed a significant decline in IPD isolates (60.2% in OPD vs. 38.9% in IPD; p = 0.0046). In contrast, doxycycline susceptibility in Klebsiella spp. showed no significant difference (73.9% in OPD vs. 66.7% in IPD). For Klebsiella spp. tetracycline susceptibility in IPD isolates was moderate at 66.7% with no available data for OPD isolates. A study has proposed doxycycline as an alternative treatment for UTI, especially for patients with limited oral options due to allergies or antibiotic-resistant organisms. However, the 2010 IDSA guidelines for uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis do not recommend doxycycline as an oral treatment option for UTI.16

Cotrimoxazole, a combination of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg) has been a first-line UTI therapy since the 1960s. It is effective against most Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and taken orally twice daily for 3 days is the therapy of choice for UTIs in women.14,17,18 Susceptibility in E. coli remained moderate and show no significant variation between OPD and IPD isolates (53.9% in OPD vs. 50% in IPD; p = 0.6712). A significant decline in susceptibility was observed in IPD isolates for Klebsiella spp. (84.8% in OPD vs. 66.7% in IPD). This study demonstrates that the susceptibility pattern of cotrimoxazole in the community was good (84.8%) indicating that cotrimoxazole can still be used for uncomplicated UTIs in outpatients in our geographic region.

Fosfomycin was discovered in Spain in 1969 and works by disrupting cell wall synthesis in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.19 E. coli showed high susceptibility in both OPD and IPD isolates (100%; p = 1.0000). National survey has also documented high susceptibility in E. coli (93.7%) from urine isolates.12

Fluoroquinolones usage started in 1962 with the discovery of nalidixic acid, a by-product of chloroquine synthesis. Fluoroquinolones like ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin are widely used for treating UTIs because of their broad-spectrum activity and ability to penetrate tissues effectively.20 However, resistance to these antibiotics are becoming a growing concern particularly among uropathogens. In E. coli isolates, ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin susceptibility decreased in IPD patients (35.5% in OPD vs 23.3% in IPD; p = 0.0860) and (50.3% in OPD vs 31.3% in IPD; p = 0.0093). National AMR surveillance for urine sample has also shown resistance to ciprofloxacin which ranged from 2.9%-33%.12 This indicates widespread resistance among both community-acquired and hospital-acquired strains, with a more pronounced impact in hospital settings. For Klebsiella spp., ciprofloxacin susceptibility was notably higher in IPD isolates (72.7% in OPD vs. 100% in IPD), while norfloxacin susceptibility decreased in IPD isolates (91.2% in OPD vs. 75% in IPD).

Amoxicillin clavulanate was first introduced in 1981 to tackle the emerging β-lactamase-harbouring pathogens.21 The susceptibility to E. coli showed a significant decline in IPD (69.6% in OPD vs 42.9% in IPD; p = 0.0002). A notable reduction in susceptibility was also observed in Klebsiella isolates (65.2% in OPD vs 50% in IPD). These findings highlight that while beta-lactamase inhibitors remain effective for community-acquired infections, there is a significant rise in resistance within hospital settings particularly for E. coli and Klebsiella spp.

Aminoglycosides, introduced into clinical use in 1944 are potent, broad-spectrum antibiotics that act through inhibition of protein synthesis.22 Susceptibility to gentamicin were similar in E. coli isolates from both settings (75% in OPD vs. 78.1% in IPD; p = 0.7390), indicating no significant difference. High susceptibility to amikacin were observed in E. coli isolates (97% in OPD vs. 90.6% in IPD; p = 0.1338). Amikacin susceptibility in E. coli isolates from national AMR urine data has shown a decrease from 86.4% in 2017 to 71.1% in 2023.12 Amikacin susceptibility and gentamicin susceptibility in Klebsiella spp. were slightly lower in OPD isolates (90.9% in OPD vs. 100% in IPD) and (93.8% in OPD vs. 100% in IPD). Geographic regional strains and antibiotic usage pressure dictates the variability in susceptibility. Judicious use of aminoglycosides and stringent antimicrobial stewardship has to be incorporated to prevent resistance, since national data on amikacin susceptibility has shown a decrease from 56.9% to 44.4% over a period of 7 years in Klebsiella spp.12

Third-generation cephalosporins, such as cefotaxime and ceftazidime are particularly effective against Gram-negative bacteria. They are often prescribed for infections resistant to earlier-generation cephalosporins or other β-lactam antibiotics.23 Susceptibility of cefotaxime and ceftazidime for E. coli decreased in IPD isolates (47.3% in OPD vs. 19.4% in IPD; p = 0.0001) and (61.5% in OPD vs. 25% in IPD; p = 0.0001). This low susceptibility in 3rd generation cephalosporin has also been observed in a nationwide surveillance among E. coli from urine isolates.12 In Klebsiella spp., cefotaxime susceptibility was lower in IPD isolates (75.8% in OPD vs. 50% in IPD) and ceftazidime showed 100% susceptibility in IPD isolates (73.7% in OPD vs. 100% in IPD). Although, decreasing susceptibility to Klebsiella spp. for cefotaxime and ceftazidime over 7 years period has been documented from national surveillance (27.3%-21.9% and 23.4%-17.9%).12 Decades of overuse and misuse have led to widespread resistance in third-generation cephalosporins which make these antibiotics less effective and nearly unusable as empiric therapy in seriously ill patients in tertiary care practices.

Carbapenems are highly potent, broad-spectrum antibiotics and their unique structure makes them resistant to most β-lactamase enzymes, including metallo-β-lactamases (MBL) and extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL).24,25 Imipenem became the first carbapenem introduced in 1985 for treating complex infections.26 In our study, imipenem susceptibility to E. coli showed 100% in OPD and IPD isolates. Meropenem also performed well with a slight non-significant difference in susceptibility (100% in OPD vs. 95% in IPD; p = 0.0594) (Table 2). For Klebsiella spp., there was a stark contrast in susceptibility to carbapenems. Imipenem showed 85.7% effectiveness in OPD isolates but was completely ineffective in IPD (0%). This highlights the emergence of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella strains in hospitals, likely due to the selective pressure of higher antibiotic use. The rising worldwide trend in CRE infections has been attributed to high mortality and morbidity among vulnerable populations in a hospital setting.27,28

Table 2:

Comparison of antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Gram-negative bacteria in urine samples between obstetrics and gynaecology OPD and IPD

| Antibiotics | E. coli | p-value | Klebsiella sp. | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gynae OPD (193) | Gynae IPD (32) | Gynae OPD (36) | Gynae IPD (4) | Gynae OPD (1) | Gynae IPD (1) | ||

| Gentamicin (10 µg) | 75.1 (145/193; 95% CI 68.6-80.8) | 78.1 (25/32; 95% CI 60.0-89.8) | 0.7390 | 93.8 (34/36; 95% CI 79.9-98.3) | 100.0 (4/4; 95% CI 39.8-100.0) | 0.0 (0/1; 95% CI 0.0-97.5) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) |

| Amikacin (30 µg) | 96.9 (187/193; 95% CI 93.4-98.9) | 90.6 (29/32; 95% CI 75.0-97.4) | 0.1338 | 90.9 (33/36; 95% CI 76.4-96.7) | 100.0 (4/4; 95% CI 39.8-100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) |

| Cefotaxime (30 µg) | 47.2 (91/193; 95% CI 39.9-54.4) | 19.4 (6/32; 95% CI 9.2-36.8) | 0.0001 | 75.8 (27/36; 95% CI 60.9-86.2) | 50.0 (2/4; 95% CI 15.7-84.3) | NR | NR |

| Ceftazidime (30 µg) | 61.7 (119/193; 95% CI 54.4-68.5) | 25.0 (8/32; 95% CI 13.6-42.1) | 0.0001 | 73.7 (27/36; 95% CI 58.7-85.0) | 100.0 (4/4; 95% CI 39.8-100.0) | 0.0 (0/1; 95% CI 0.0-97.5) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) |

| Ciprofloxacin (5 µg) | 35.2 (68/193; 95% CI 29.0-42.3) | 21.9 (7/32; 95% CI 11.0-39.2) | 0.0860 | 72.7 (26/36; 95% CI 57.2-84.1) | 100.0 (4/4; 95% CI 39.8-100.0) | 0.0 (0/1; 95% CI 0.0-97.5) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) |

| Norfloxacin (10 µg) | 50.3 (97/193; 95% CI 43.0-57.5) | 31.3 (10/32; 95% CI 18.0-48.0) | 0.0093 | 91.2 (33/36; 95% CI 77.0-97.1) | 75.0 (3/4; 95% CI 30.1-95.4) | ND | ND |

| Imipenem (10 µg) | 100.0 (193/193; 95% CI 98.1-100.0) | 100.0 (32/32; 95% CI 88.8-100.0) | 1.0000 | 85.7 (31/36; 95% CI 70.6-93.6) | 0.0 (0/4; 95% CI 0.0-60.2) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) |

| Meropenem (10 µg) | 100.0 (193/193; 95% CI 98.1-100.0) | 93.8 (30/32; 95% CI 79.2-98.4) | 0.0594 | 93.3 (28/30; est) | 100.0 (4/4; 95% CI 39.8-100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) |

| Cotrimoxazole (1.25/23.75 µg) | 53.9 (104/193; 95% CI 46.7-61.0) | 50.0 (16/32; 95% CI 33.0-67.0) | 0.6712 | 84.8 (31/36; 95% CI 69.9-92.6) | 66.7 (2/3; 95% CI 20.2-94.4) | ND | ND |

| Piperacillin-Tazobactam (100/10 µg) | 96.4 (186/193; 95% CI 92.7-98.5) | 44.8 (14/32; 95% CI 30.3-60.3) | 0.0001 | 90.9 (33/36; 95% CI 76.4-96.7) | 33.3 (1/3; 95% CI 0.8-90.6) | 0.0 (0/1; 95% CI 0.0-97.5) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) |

| Amoxy-clav (20/10 µg) | 69.4 (134/193; 95% CI 62.4-75.8) | 42.9 (14/32; 95% CI 28.1-59.0) | 0.0002 | 65.2 (23/35; est) | 50.0 (2/4; 95% CI 15.7-84.3) | – | – |

| Nitrofurantoin (300 µg) | 100.0 (193/193; 95% CI 98.1-100.0) | 93.8 (30/32; 95% CI 79.2-98.4) | 0.0289 | 0.0 (0/36; 95% CI 0.0-9.6) | 25.0 (1/4; 95% CI 0.6-80.6) | – | – |

| Fosfomycin (200 µg) | 100.0 (193/193; 95% CI 98.1-100.0) | 100.0 (32/32; 95% CI 88.8-100.0) | 1.0000 | ND | 0.0 (0/4; 95% CI 0.0-60.2) | – | – |

| Tetracycline (30 µg) | ND | 38.9 (12/32; 95% CI 24.5-56.0) | – | ND | ND | – | – |

| Doxycycline (30 µg) | 60.2 (116/193; 95% CI 53.1-67.0) | 38.9 (12/32; 95% CI 24.5-56.0) | 0.0046 | 73.9 (27/36; 95% CI 58.7-85.0) | 66.7 (2/3; 95% CI 20.2-94.4) | – | – |

NR-Not recommended according to CLSI; ND-not done; p < 0.05 was considered significant.

FDA approved the use of piperacillin tazobactam combination (β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor) in 1993 to treat patients with moderate to severe infections caused by piperacillin resistant, piperacillin tazobactam susceptible β-lactamase producing strains of bacteria.29 Susceptibility to E. coli showed a significant decline in IPD isolates compared to OPD isolates (96.3% in OPD vs 44.8% in IPD; p = 0.0001). The declining trend in E. coli susceptibility to piperacillin-tazobactam has been observed from national surveillance studies which showed 73.7% in 2017 to 56.1% in 2023.12 A notable reduction in susceptibility was also observed in Klebsiella spp. isolates dropping significantly in IPD isolates (90.9% in OPD vs 33.3% in IPD). Klebsiella spp. decreasing susceptibility to piperacillin-tazobactam from 52.5% in 2017 to 46.7% in 2023 has been observed in national surveillance survey from urine sample.12 These findings highlight that while beta-lactamase inhibitors remain effective for community-acquired infections, there is a significant rise in resistance within hospital settings particularly for E. coli and Klebsiella spp.

Gram-positive bacteria

Enterococcus species exhibited universal susceptibility to vancomycin, linezolid, and teicoplanin (100%) in both OPD and IPD isolates. However, penicillin G showed no effectiveness in IPD isolates (100% vs 0%). Similarly, ampicillin was 100% susceptible compared to IPD isolates (33.3%). Nitrofurantoin displayed high and stable susceptibility in both OPD and IPD isolates (75%). Doxycycline susceptibility was moderate in OPD isolates (50%) but significantly reduced in IPD isolates (16.7%). High-level gentamicin (HLG) susceptibility decreased in IPD isolates (50% in OPD vs. 25% in IPD) (Table 3).

Staphylococcus aureus shows excellent susceptibility (100%) to key agents like nitrofurantoin, gentamicin, linezolid, teicoplanin, vancomycin in OPD and IPD settings

(Table 3). However, resistance to Penicillin G and cefoxitin indicates methicillin-resistant strains, necessitating caution in empirical therapy. Staphylococcus saprophyticus showed universal susceptibility of 100% in both OPD and IPD isolates for nitrofurantoin, gentamicin, teicoplanin, linezolid and vancomycin (Table 3).

Table (3):

Comparison of antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Gram-positive bacteria in urine samples between obstetrics and gynaecology OPD and IPD

| Antibiotics | Staphylococcus aureus | Enterococcus sp. | Staphylococcus saprophyticus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gynae OPD (1) | Gynae IPD (1) | p-value | Gynae OPD (5) | Gynae IPD (18) | p-Value | Gynae OPD (10) | Gynae IPD (1) | p-value | |

| Penicillin G (10 U) | 0.0 (0/1; 95% CI 0.0–97.5) | 0.0 (0/1; 95% CI 0.0–97.5) | 1.0000 | 100.0 (5/5; 95% CI 47.8–100.0) | 0.0 (0/18; 95% CI 0.0–17.6) | 0.0001 | 37.5 (4/10; 95% CI 13.7–71.2) | 0.0 (0/1; 95% CI 0.0–97.5) | 0.0001 |

| Ampicillin (30 µg) | – | – | – | 100.0 (5/5; 95% CI 47.8–100.0) | 33.3 (6/18; 95% CI 16.1–56.4) | 0.0001 | – | – | – |

| Tetracycline (30 µg) | – | – | – | ND | 0 | – | 100.0 (10/10; 95% CI 69.2–100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 1.0000 |

| Doxycycline (30 µg) | 0 | ND | – | 50.0 (3/5; 95% CI 20.1–79.9) | 16.7 (3/18; 95% CI 5.0–39.6) | 0.0001 | 80.0 (8/10; 95% CI 44.4–96.5) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 0.0001 |

| Cefoxitin (30 µg) | ND | 0 | – | – | – | – | 40.0 (4/10; 95% CI 15.3–71.8) | 0.0 (0/1; 95% CI 0.0–97.5) | 0.0001 |

| Erythromycin (15 µg) | – | – | – | ND | 0 | – | ND | 0 | – |

| Nitrofurantoin (300 µg) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 1.0000 | 75.0 (4/5; 95% CI 34.9–96.8) | 75.0 (14/18; 95% CI 50.9–90.2) | 1.0000 | 100.0 (10/10; 95% CI 69.2–100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 1.0000 |

| Norfloxacin (10 µg) | 0.0 (0/1; 95% CI 0.0–97.5) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 0.0001 | 25.0 (1/5; 95% CI 1.3–65.1) | 0.0 (0/18; 95% CI 0.0–17.6) | 0.0001 | ND | ND | – |

| Ciprofloxacin (5 µg) | ND | 0 | – | ND | 0 | – | – | – | – |

| Gentamicin (10 µg) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 1.0000 | – | – | – | 100.0 (10/10; 95% CI 69.2–100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 1.0000 |

| High level gentamicin (120 µg) | NR | NR | – | 50.0 (2/4) | 25.0 (4/16) | 0.0004 | – | – | – |

| Vancomycin | ND | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | – | 100.0 (5/5; 95% CI 47.8–100.0) | 100.0 (18/18; 95% CI 81.5–100.0) | 1.0000 | 0.0 (0/10; 95% CI 0.0–30.8) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) | 0.0001 |

| Teicoplanin (30 µg) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 1.0000 | 100.0 (5/5; 95% CI 47.8–100.0) | 100.0 (18/18; 95% CI 81.5–100.0) | 1.0000 | 100.0 (10/10; 95% CI 69.2–100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) | 1.0000 |

| Linezolid (30 µg) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5–100.0) | 1.0000 | 100.0 (5/5; 95% CI 47.8–100.0) | 100.0 (18/18; 95% CI 81.5–100.0) | 1.0000 | 100.0 (10/10; 95% CI 69.2–100.0) | 100.0 (1/1; 95% CI 2.5-100.0) | 1.0000 |

NR-Not recommended according to CLSI; ND-Not done; p < 0.05 was considered significant.

The marked differences in susceptibility patterns between OPD and IPD isolates have important implications for empiric management of UTIs in obstetrics and gynaecology. In OPD settings, nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin remain reliable empiric options for E. coli; however, the complete resistance of Klebsiella spp. to nitrofurantoin underscores the need for culture-based confirmation when this pathogen is suspected. In IPD settings, broader resistance across multiple antibiotic classes, including significant reductions in susceptibility to β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors, fluoroquinolones, and third-generation cephalosporins, limits the utility of conventional oral agents. The absence of carbapenem susceptibility in IPD Klebsiella spp. isolates further highlights emerging hospital-acquired multidrug-resistance. These findings emphasize the need for setting-specific empiric guidelines with routine culture and susceptibility testing particularly critical in hospitalized patients.

The antimicrobial resistance trends observed in this study, particularly in E. coli and Klebsiella spp. underscore the urgent need for continuous regional surveillance, robust infection control measures and antibiotic stewardship programs. Our single centre study emphasize on microbiological report prior to empirical therapy of nitrofurantoin used in UTI caused by Klebsiella spp. for our geographical region. By comparing these findings with national surveillance data, the importance of a coordinated effort to address AMR in obstetrics and gynaecology settings becomes evident. Further research is essential to refine treatment protocols and mitigate the impact of multidrug-resistant infections on vulnerable populations.

Limitations of the study

This retrospective, single-center study is subject to inherent limitations including potential sampling bias, small subgroup sizes for several taxa and absence of ESBL/CRE phenotyping. Lack of pregnancy-status stratification may also have influenced pathogen and resistance distributions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analysed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Mera-Lojano LD, Mejía-Contreras LA, Cajas-Velásquez SM, Guarderas-Muñoz SJ. Prevalence and risk factors of urinary tract infection in pregnant women. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2023;61(5):590-596.

Crossref - Zhou Y, Zhou Z, Zheng L, et al. Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Uropathogenic Escherichia coli: Mechanisms of Infection and Treatment Options. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13):10537.

Crossref - Venkataraman R, Manuel GG, Rai NJ, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, causative organism and antibiotic susceptibility of catheter associated urinary tract infections. Int J Res Med Sci. 2023;12(1):183-187.

Crossref - Jain M, Kaushal R, Bharadwaj M. Infection surveillance analysis of catheter associated urinary tract infections in obstetrics and gynecology department of a tertiary care hospital of Central India. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017;7(1):215-219.

Crossref - Kalpana P, Trivedi P, Bhavsar P, Patel K, Yasobant S, Saxena D. Evidence of Antimicrobial Resistance from Maternity Units and Labor Rooms: A Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) Study from Gujarat, India. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(4):648.

Crossref - Mareș C, Petca RC, Popescu RI, Petca A, Geavlete BF, Jinga V. Uropathogens’ Antibiotic Resistance Evolution in a Female Population: A Sequential Multi-Year Comparative Analysis. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;12(6):948.

Crossref - Patil G, Patil D, Patil A, Shrikhande S. Microbiological Profile and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Pattern of Uropathogens Isolated From Pregnant Women Attending a Tertiary Care Hospital in Central India. Cureus. 2024;16(10):e70798.

Crossref - Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 33rd ed. CLSI Supplement M100. CLSI; 2023. https://vchmedical.ajums.ac.ir/uploads/6/2024/Aug/11/A_CLSI_2023_M100_Performance_Standards_for_Antimicrobial_Susceptibility%20(1).pdf

- Sugianli AK, Ginting F, Parwati I, de Jong MD, van Leth F, Schultsz C. Antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens in the Asia-Pacific region: a systematic review. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3(1):dlab003.

Crossref - Mohapatra S, Panigrahy R, Tak V, et al. Prevalence and resistance pattern of uropathogens from community settings of different regions: an experience from India. Access Microbiol. 2022;4(2):000321.

Crossref - Cunha BA. Nitrofurantoin: an update. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989;44(5):399-406.

- Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). Annual Report Antimicrobial resistance Research and Survellance Network. 2024. https://www.icmr.gov.in/icmrobject/uploads/Report/1763981012_icmramrsnannualreport2024.pdf

- David LS, Varunashree ND, Ebenezer ED, et al. Profile of uropathogens in pregnancy over 5 years from a large tertiary center in South India. Indian J Med Sci. 2022;74(3):112-117.

Crossref - Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):e103-e120.

Crossref - Chopra I, Roberts M. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65(2):232-260.

Crossref - Zheng T, Mehta M, Stilwell A, Demenagas N. 2849. Doxycycline for the treatment of urinary tract infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(Suppl 2):ofad500.2459.

Crossref - Katzung BG, Trevor AJ. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, nonopioid analgesics, and drugs used in gout. In: Katzung BG, ed. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. 11th ed. McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009:621-642.

- Parsons KF, Poitiers JI, Fall M, et al. Urological infection. In: European Association of Urology Guidelines. EAU. 2014:832.

- Michalopoulos AS, Livaditis IG, Gougoutas V. The revival of fosfomycin. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(11):e732-e739.

Crossref - Bush NG, Diez-Santos I, Abbott LR, Maxwell A. Quinolones: mechanism, lethality and their contributions to antibiotic resistance. Molecules. 2020;25(23):5662.

Crossref - Veeraraghavan B, Bakthavatchalam YD, Sahni RD. Orally administered amoxicillin/clavulanate: current role in outpatient therapy. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10(1):15-25.

Crossref - Krause KM, Serio AW, Kane TR, Connolly LE. Aminoglycosides: an overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6(6):a027029.

Crossref - Bui T, Patel P, Preuss CV. Cephalosporins. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Codjoe FS, Donkor ES. Carbapenem resistance: a review. Med Sci. 2017;6(1):1.

Crossref - Papp-Wallace KM, Endimiani A, Taracila MA, Bonomo RA. Carbapenems: past, present, and future. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(11):4943-4960.

Crossref - Heo YA. Imipenem/Cilastatin/Relebactam: A Review in Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. Drugs. 2021;81(3):377-388.

Crossref - Lee CR, Lee JH, Park KS, Kim YB, Jeong BC, Lee SH. Global dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: Epidemiology, Genetic Context, Treatment Options, and Detection Methods. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:895.

Crossref - Sharma A, Gupta VK, Pathania R. Efflux pump inhibitors for bacterial pathogens: From bench to bedside. Indian J Med Res. 2019;149(2):129-145.

Crossref - Desai NR, Shah SM, Cohen J, McLaughlin M, Dalal HR. Zosyn (piperacillin/tazobactam) reformulation: expanded compatibility with lactated Ringer’s and aminoglycosides. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(2):303-314.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.