ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Meloidogyne enterolobii, widely known as the guava root-knot nematode, poses a growing challenge to global agriculture because of its broad host spectrum and capacity to bypass resistance genes in various crops. The present study focuses on assessing the ability of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) to induce resistance against root-knot nematodes as an alternative to chemicals. Two AMF isolates, Glomus mosseae and Rhizophagus irregularis, isolated from the guava rhizosphere, were evaluated for their bio-efficacy against M. enterolobii. In vitro twin-chamber assays and root-exudate studies showed that Glomus mosseae enabled a nematode reduction of 85.5% in juvenile penetration and 91.2% in egg hatching in comparison with non-mycorrhizal controls. GC-MS analysis of root exudates from AMF-inoculated and control plants identified octadecanoic acid, heptacosane, acetic acid, and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol in R. irregularis-inoculated plants, and dodecyl acrylate, acetic acid, and trilinolein in G. mosseae-inoculated plants. Pot experiment revealed that G. mosseae significantly enhanced growth parameters, including shoot length (59.4 cm), shoot weight (33.7 g), root length (32.5 cm), and root weight (11.78 g), in comparison to the control plants. The combined application of G. mosseae and R. irregularis significantly enhanced soil and plant health, increasing spore counts (285 per 50 g soil), mycorrhizal colonization (95%), dehydrogenase enzyme activity (61.2 nmol TPF g-1 h-1), and glomalin-related soil proteins (1.21 mg glomalin/g soil). Additionally, this treatment markedly reduced M. enterolobii infection in guava, with fewer galls (6.3) and egg masses (0.92 per 5 g root), highlighting its potential as an effective biocontrol strategy for guava cultivation.

Biological Control, Glomus mosseae, Meloidogyne enterolobii, Rhizophagus irregularis, Root exudates

Guava (Psidium guajava L.,) is a versatile fruit crop cultivated globally, producing approximately 2.3 million tons annually.1 Native to Mexico and Central America, it has gained prominence in tropical and subtropical regions due to its adaptability to diverse climates and soil conditions.2 Widely cultivated in Asia and the Americas, guava is valued for its rich nutritional profile, which includes high levels of vitamins C and A, essential minerals, and antioxidants, making it a beneficial and health-promoting fruit. India leads global guava production, yielding 5.59 million metric tons annually. In recent years, the guava root-knot nematode, M. enterolobii Yang and Eisenback (previously Meloidogyne mayaguensis), has become a major threat to farmers, causing yield losses of up to 65%.3 M. enterolobii infection in guava reduces plant growth, lifespan, yield quality, and resilience to abiotic stresses. Symptoms include yellowing, wilting, stunted growth, extensive root galling, and increased vulnerability to secondary infections, such as Fusarium solani, in guava.

Root knot nematodes are soil-dwelling microscopic organism that belongs to the family Heteroderidae, known for their devastating impact on crops worldwide as one of the most economically significant plant-parasitic nematodes. These obligate endoparasites invade the roots of more than 2,000 plant species, including vegetables, fruits, and ornamentals, inducing distinctive galls or “knots” that interfere with nutrient and water absorption, resulting in stunted growth, wilting, reduced yields, and heightened vulnerability to other pathogens. The life cycle of root-knot nematodes includes egg, juvenile, and adult stages, with J2 second-stage juveniles infiltrating plant roots to create feeding sites, triggering the formation of multinucleate giant cells that sustain their growth. Their extensive host range, adaptability to various soil conditions, and intricate interactions with soil microbes amplify their detrimental effects on crop productivity.4 The most economically significant root-knot nematode species are Meloidogyne incognita, M. javanica, M. arenaria, and M. hapla, each uniquely adapted to specific host plants and environmental conditions. Root-knot nematodes cause about 5% of worldwide crop losses, with their impact worsened by secondary infections and environmental stresses.

Managing M. enterolobii poses significant challenges for guava farmers. Chemical nematicides, including Carbofuran, Oxamyl, Fluopyram, Fenamiphos, and Fluensulfone, are frequently used to control nematodes.5 The application of chemical nematicides has several significant limitations, including the need for frequent treatments, high costs, environmental contamination, toxicity to non-target organisms (including human applicators), and the risk of developing nematicide resistance.6 Biological control has recently gained attention as a sustainable alternative to chemical methods, with antagonists such as Purpureocillium lilacinum, Pochonia chlamydosporia, Trichoderma harzianum, Trichoderma asperellum, AMF, Bacillus subtilis, and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens showing promise in managing M. enterolobii.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), part of the Glomeromycotina subphylum, form mutualistic partnerships with over 80% of crop plants, including most agricultural and horticultural species. They acquire photosynthetic carbon from host plants, enhancing nutrient uptake, promoting plant growth by mitigating biotic and abiotic stresses, and improving soil stability.7 AMF primarily enhances plant nutrient absorption, especially of immobile nutrients such as phosphorus, zinc, and copper, and to a lesser degree, nitrogen, in low-fertility soils.8,9 In general, mycorrhizal plants exhibit enhanced growth and a more robust appearance compared to non-mycorrhizal plants, particularly in low-fertility soils.10 Fungi produce antibiotic-like compounds that protect plants from specific pathogens. This suggests that these beneficial microbes may colonize plants by modifying their defense systems, allowing them to reside within the plant without triggering an immune response. Furthermore, these microbes may access nutrients unavailable to the plant or generate substances that bolster the plant’s resilience to environmental stress.11 AMF defend against pathogens, serving as an effective tool for biological pest management. AMF can reduce Meloidogyne galls and egg counts while improving plant growth and nutrient absorption, potentially outperforming chemical pesticides in efficacy.12,13 AMF affects Meloidogyne infection at various stages by decreasing root attractiveness to nematodes and hindering giant cell formation in galls. In mycorrhizal plants infected with Meloidogyne, there is heightened production of protective compounds, such as phenolics, and defense-related enzymes like peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase. The exact mechanisms behind mycorrhizae-induced resistance to plant-parasitic nematodes remain unclear. Nonetheless, recent research indicates that AMF-triggered suppression of nematode reproduction is systemic and involves the class III chitinase gene.14 This boost in defence genes and pathways is believed to contribute to the plant’s increased tolerance to Meloidogyne infection.15,16 In our study, we sought to address this gap by examining the diversity of culturable rhizosphere AMF from various niches of a guava cultivar and evaluating their nematicidal potential through genomic, metabolomic, and bioinformatics methods to create a sustainable biocontrol strategy.

Isolation of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi from guava plants

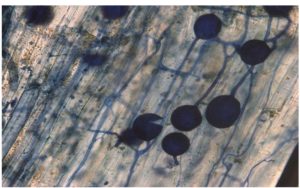

Soil samples from the guava rhizosphere at the Horticultural College and Research Institute (HC&RI), Periyakulam, Theni, were collected and maintained in maize under greenhouse conditions. Collect 100-500 g of rhizosphere soil at a depth of 10-20 cm, combine with 1-2 L of water, stir thoroughly, and let settle for 10-30 seconds.17,18 Pour the supernatant through a stack of sieves (500, 250, 100, and 45 µm) to collect spores, rinse the residues with water, and transfer them to a Petri dish. Using a stereomicroscope (10-40x), separate spores by size, color, and morphology with a micropipette or fine needle, and clean them with sterile water or 0.05% sodium hypochlorite. For morphological identification, mount spores in polyvinyl lacto-glycerol (PVLG) or Melzer’s reagent, observe at 40-100x, and classify them based on spore traits using INVAM reference guides. The AM fungi inoculum was formulated using vermiculite as the carrier, containing 100 propagules per gram, consisting of spores, hyphae, and mycorrhizal roots (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Microscopic cross-section of guava roots colonized by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, showing extensive hyphal penetration into cortical cells and formation of arbuscules for nutrient exchange. Stained guava root sample highlighting key AM fungal structures, including vesicles and intraradical mycelium, confirming successful colonization

Morphological and molecular characterization of AMF

Fungal DNA was extracted and amplified using the primers MID1-LSUD2f

(5′-GTGAAATTGTTGAAAGGGAAAC-3′) and MID17-LSUmBr (5′-AACACTCGCAYAYATGYTAGA-3′). The PCR reaction mixture contained 20 ng of DNA, 0.3 µl of Taq DNA polymerase, 2.5 µl of 10X Taq buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM of each dNTP, and 10 pM of each primer. The PCR protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing at 60 °C for 2 min, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.19 The amplified products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel. The PCR products were sequenced, and their similarities were assessed using the BLASTN tool. The sequences were submitted to the NCBI-GenBank database, and accession numbers were acquired.

Isolation and molecular confirmation of M. enterolobii

Guava roots affected by M. enterolobii were gathered from multiple guava cultivation sites in the Theni district of Tamil Nadu, India. Egg masses were meticulously gathered from infested roots, with soil debris thoroughly removed by rinsing under running water. The collected egg masses were incubated at room temperature (26 ± 2 °C, 80% relative humidity) for four days. The freshly hatched J2 were inoculated into guava plants maintained at the Department of Plant Protection, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, HC&RI, Periyakulam. Molecular characterization of the nematodes was performed to verify the associated species. Genomic 18S rRNA was extracted from M. enterolobii eggs, juveniles, and adult females and used as a template for PCR amplification with the primers TW 81-GTTTCCGTAGGTGAACCTGC and AB 28-ATATGCTTAAGTTCAGCGGGT. The PCR protocol included an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 sec, annealing at 54 °C for 30 sec, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products (10 µL) were examined via gel electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel in TAE buffer at 70 V for 50 minutes. The amplified products were visualized under UV light using a Vilber E-box gel documentation system. The amplified DNA was sequenced through an outsourced service provided by M/s. Biokart India Pvt. Ltd. in Bangalore. Gene homology was assessed using NCBI BLAST against the non-redundant nucleotide (nr database). The resulting sequences were deposited in the NCBI-GenBank database, and accession numbers were obtained.

Twin-chamber assay for nematode penetration

Guava grafts were planted in 1 kg pots filled with a sterilised potting mixture of soil:sand:farmyard manure (1:1:1, v/v). Each graft was inoculated with 100 g of maize-root powder containing approximately 10 infective propagules per gram of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) isolates G. mosseae and R. irregularis. After six weeks, plants were gently uprooted and root samples were taken to assess AMF colonisation using standard staining and microscopic examination. Separate sets of guava grafts were maintained for each AMF isolate. Once colonisation was confirmed, plants were transferred to twin-chamber systems (2 kg pots each) interconnected via a 30 cm-long, 3-inch-diameter PVC pipe with a central 13 cm slit (Figure 2). Two days after transplanting, 4,000 freshly hatched second-stage juveniles (J2) of M. enterolobii were inoculated at the slit location while the pots were maintained at field capacity moisture.13

Figure 2. Twin-chamber assay evaluating nematode penetration in Non-mycorrhizal plant (control) and Mycorrhizal plant (AMF-treated plants), highlighting differences in nematode behaviour and root colonization

Five treatments were employed in a completely randomised design with four replicates each: (a) uninoculated control plants; (b) plants inoculated with R. irregularis in both compartments; (c) plants inoculated with G. mosseae in both compartments; (d) control plant in the right chamber and R. irregularis-inoculated plant in the left chamber; (e) control plant in the right chamber and G. mosseae-inoculated plant in the left chamber. Fifteen days after inoculation, roots were stained with acid-fuchsin in lactophenol and examined under a light microscope at 40 × magnification to count penetrated nematodes. The penetration rate (%) was calculated as (Pp / Pi) × 100, where Pp represents the number of juveniles that penetrated and Pi the initial inoculated population.

Collection of Guava Root exudates for nematicidal bioassay

An experimental setup was established to collect root exudates from guava grafts. Sixty-day-old guava grafts, colonized with G. mosseae or R. irregularis as well as uncolonized plants, were individually selected, carefully uprooted, and had their roots cleaned of all soil particles. The roots were then submerged in 50 mL of 0.01 mol L-1 KOH for 5 minutes. Following this, the roots were thoroughly rinsed with running tap water and then distilled water. Subsequently, the plants were placed in a pre-sterilized Leonard jar assembly containing 250 g of glass beads and sand. The stem end of the Leonard jar was sealed with aluminum foil perforated with pin-sized holes and placed in a 500 mL Erlenmeyer flask (Figure 3). The setup was watered regularly for 7 days.19,20

Egg hatching assay

A 5 µL suspension containing 100 M. enterolobii eggs was obtained from a pure culture maintained in a greenhouse. The experiment was conducted using 5 cm diameter Petri dishes, each containing 1 mL of 1% root exudates from the stock solution and 100 M. enterolobii eggs. Root exudates from guava plants without arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi were used as the positive control, while eggs in tap water served as the total control. Egg hatching was assessed at 24, 48, and 72 h post-incubation. The number of hatched juveniles was counted and expressed as a percentage.21

Profiling of organic compounds in root exudates through GC-MS

The collected root exudates were filtered using a 0.2 µm syringe filter and stored at -20 °C until required. Root exudates from AM fungi-colonized and non-treated guava plants were extracted with ethyl acetate and analyzed via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The experiments were conducted in triplicate. Metabolites in the root exudates were analyzed using the online software MetaboAnalyst 5.0.22

Glass house experiment

A sterilized potting mixture (soil:sand:FYM, 1:1:1) was used to fill 5 kg pots. The mixture was inoculated with arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) spores at a rate of 100 spores per gram, according to the treatment. Ninety day-old Lucknow 49 guava grafts, with surface-sterilized roots, were transplanted into the pots and maintained for 90 days. The experiment followed a completely randomized design (CRD) with three replicates and six treatments: T1 (Control, Nematode alone), T2 (R. irregularis + M. enterolobii), T3 (G. mossae + M. enterolobii), T4 (R. irregularis + G. mossae + M. enterolobii), T5 (Purpureocillium lilacinum + M. enterolobii), T6 (Carbofuran + M. enterolobii). Fifteen days after transplanting, 5,000 freshly hatched M. enterolobii second-stage juveniles (J2) were inoculated per pot by creating three holes around the plant, which were then covered with sterilized soil.

Observations on plant height, number of leaves, root weight, and shoot weight, mycorrhizal colonization, AMF spore density,23 glomalin production and dehydrogenase activity,24 nematode population in the soil and root,25 reproductive index, and gall index26 was also estimated.

Data analysis

Statistical assessment for both plant growth parameters and nematode pathogenicity data was carried out using the Shapiro-Wilk and Bartlett’s tests, respectively. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was executed to detect significant differences in the respective parameters concerning variations in nematode population density. At a 5% significance level, post hoc Tukey’s HSD test was implemented to pinpoint noteworthy differences among different treatment groups.

Identification of AM Fungi

Molecular identification of AM fungi was conducted using a thermocycler. The PCR products generated 1500 bp DNA fragments, which were sequenced, compared with the NCBI database, and submitted to GenBank, receiving accession numbers Glomus mosseae GlomoMax1 (PQ669218) and Rhizophagus irregularis RhizoMax1 (PQ669217). All consensus sequences obtained in this study showed high similarity (up to 99%) with GenBank’s most closely related sequences.

Identification of nematode species

Morphological and molecular analyses were conducted to identify nematodes associated with guava. Examination of the posterior cuticular pattern revealed an oval-shaped dorsal arch, moderately high to high, with squarish and rounded features, and smooth to coarse striae.

PCR amplification of the 18S rRNA region from various life stages of Meloidogyne enterolobii produced 600 bp fragments. BLAST analysis showed 98% sequence similarity with the reference sequence of M. enterolobii. The aligned DNA sequence was deposited in the GenBank database and assigned accession number OQ642284.

Twin-chamber assay for nematode penetration study

The twin-chamber assay for guava grafts showed robust mycorrhizal colonization in the roots, with an average colonization intensity of 86 ± 3% (Figures 1 and 2). When plants from the same treatment were placed on both sides of the connecting bridge, nematode penetration was comparable in both pots. However, M. enterolobii J2 penetration was significantly higher in non-mycorrhizal control plants compared to mycorrhizal plants in the AMF treatment, with penetration rates of approximately 55% in the control and 9.5% in the AMF treatment. Only about half of the inoculated nematode population reached the guava plant roots. In mixed treatments, where a control plant was in the right compartment and a mycorrhizal plant in the left, the control plant exhibited higher nematode penetration (Table 1). Juvenile penetration stopped 8 days post-inoculation. No notable difference was observed in the total nematode counts between control and mycorrhizal pots within the same treatment. The findings suggest that mycorrhizal colonization significantly reduced J2 nematode penetration. Additionally, root exudates from mycorrhizal plants likely contributed to a substantial decrease in nematode penetration compared to non-mycorrhizal plants.

Table (1):

Penetration of M. enterolobii nematodes up to 15 days after inoculation in control and Mycorrhizae roots of Guava

| Strains | No. of juveniles penetrated inside the root of guava | Penetration rate | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | ||||||||||

| L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | |

| G. mosseae in both pot | 50 (1.69) | 60

(1.7) |

120

(2.0) |

140

(2.1) |

220

(2.3) |

240

(2.3) |

330

(2.5) |

380

(2.5) |

390

(2.5) |

380

(2.5) |

390

(2.5) |

380

(2.5) |

390

(2.5) |

380

(2.5) |

9.7 | 9.5 |

| G. mosseae in one pot | 80 (1.90) | 412

(2.6) |

110

(2.0) |

682

(2.8) |

260

(2.4) |

1432

(3.1) |

320

(2.50) |

1843

(3.2) |

320

(2.5) |

2143

(3.3) |

320

(2.5) |

2143

(3.33) |

320

(2.5) |

2143

(3.3) |

8.0 | 53.5 |

| R. irregularis in both pot | 80 (1.90) | 60

(1.7) |

90

(1.9) |

120

(2.0) |

190 (2.27) | 220

(2.34) |

290

(2.46) |

310

(2.4) |

390

(2.5) |

310

(2.4) |

390

(2.5) |

310

(2.4) |

390

(2.5) |

310

(2.4) |

9.7 | 7.7 |

| R. irregularis in one pot | 50 (1.6) | 394

(2.5) |

100

(2.0) |

712

(2.8) |

210

(2.3) |

1387

(3.1) |

290

(2.4) |

1793

(3.2) |

320

(2.5) |

1943

(3.2) |

320

(2.5) |

1943

(3.2) |

320

(2.5) |

1943

(3.28) |

8.2 | 48.5 |

| Control | 436 (2.6) | 448 (2.6) | 832 (2.9) | 817 (2.9) | 1624 (3.2) | 1632 (3.2) | 2186 (3.3) | 2298 (3.3) | 2233 (3.3) | 2215 (3.3) | 2233 (3.3) | 2215 (3.3) | 2233 (3.34) | 2215 (3.34) | 55.0 | 55.0 |

| SE.d | 0.26 | 0.53 | 0.31 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.29 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.77 | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.53 | ||

| C.D | 0.83 | 1.23 | 0.98 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 0.96 | 1.35 | 1.10 | 1.43 | 1.15 | 1.43 | 1.84 | 1.43 | 1.11 | ||

Mean of six replications with 4000 nematodes in each treatment; Figures in parenthesis Arc sine transformed values

Egg hatching assay

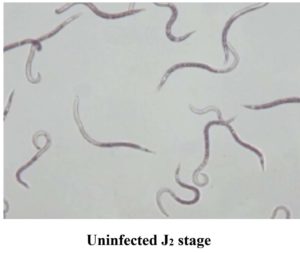

Incubation of M. enterolobii egg masses in 1% root exudates of R. irregularis and G. mosseae significantly reduced egg hatching compared to the control. No notable difference in egg hatching inhibition was observed between the root exudates of G. mosseae and R. irregularis. Guava root exudates did not affect M. enterolobii egg hatching. Even with extended incubation, the eggs failed to hatch. Egg hatching was suppressed by 95% in both R. irregularis and G. mosseae treatments (Table 2 and Figure 4).

Table (2):

Effect of AM Fungal root exudates on percent egg hatching of M. enterolobii nematodes

| Strains | Days exposed to root exudates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | |

| G. mosseae | 2 (0.3010) | 5 (0.6990) | 5 (0.6990) | 5 (0.6990) |

| R. irregularis | 2 (0.3010) | 2 (0.3010) | 2 (0.3010) | 2 (0.3010) |

| Guava root exudates | 11 (1.0413) | 32 (1.5051) | 64 (1.8061) | 95 (1.9777) |

| Control (Tap water) | 10 (1.0000) | 34 (1.5315) | 64 (1.8062) | 91 (1.9590) |

| SE.d | 0.0121 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

| C.D | 0.312 | 0.342 | 0.363 | 0.374 |

*Figures in parenthesis are log transformed values

(B)

Figure 4. (A) Healthy J2 showing active movement, (B) Dead J2 with no movement and looks straight

Profiling of organic compounds in root exudates through GC-MS

Metabolomic analysis of mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal guava plants identified 50 major compounds, with 26, 27, and 18 unique compounds detected in G. mosseae-colonized, R. irregularis-colonized, and uninoculated plants, respectively (Supplementary Table S1).

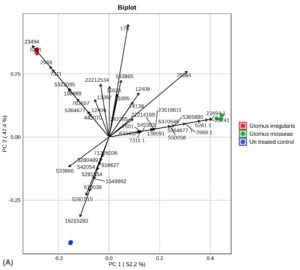

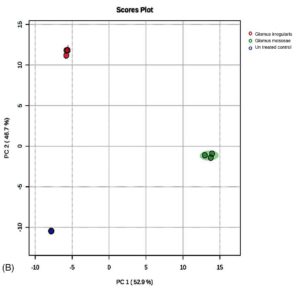

Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed distinct separation of metabolic profiles among the three groups (Figure 5a, 5b). Twelve metabolites, namely 2,5-dimethoxy-4-(methylsulfonyl)amphetamine, bicyclo(7.2.0)undec-4-ene, 4,11,11-trimethyl-8-methylene-, methyl (2-naphthyloxy)acetate, alpha-bisabolol, β-carotene, propanoic acid, 2-(aminooxy), 2,4,6-cycloheptatrien-1-one, 3,5-bis-trimethylsilyl-, (Z)-3-(pentadec-8-en-1-yl)phenol, azuleno[4,5-b]furan-2,9-dione, decahydro, (E)-coniferaldehyde, naphthalene, 1,6-dimethyl-4-(1-methylethyl), propanediamide, and 2-ethyl-2-phenyl-N, N’-bi, were uniquely detected in uninoculated plants.

Figure 5. (A) Principal component analysis of R. irregularis, G. mosseae, and untreated control. (B) Principal component analysis comparison of GC-MS metabolic profiles from R. irregularis, G. mosseae, and untreated control. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was applied to assess differences in compound abundance across fractions

Furthermore, 11 metabolites were exclusively identified in R. irregularis-colonized plants, including cyclohexene, 1-(2-methylpropyl), 1-methyl-4-benzylpiperazine, 1,3-benzenediol, 4,5-dimethyl, nonacos-1-ene, phorbol, octadecane, 3-ethyl-5-(2-ethylbutyl), octadecanoic acid, and pentacosane. Additionally, 10 metabolites were unique to G. mosseae-colonized plants, namely styrene, 7,9-di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5)deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione, methyl glycocholate, tetradecyloxirane (3TMS derivative), tetradecyloxirane, benzene, 1,12 -(3-methyl-1-propene-1,3-diyl)bis-, 3,9-epoxypregn-16-ene-14,18-diol-20-one, and 7,11-diacetoxy-3-methoxy.

Heatmap analysis of peak area percentages for all compounds across the three groups showed clear patterns (Figure 6). Acetic acid was upregulated in mycorrhizal plants, whereas caryophyllene, octacosane, and heptacosane were downregulated.

Figure 6. Heatmap analysis of rhizobacterial metabolites. Class 1: R. irregularis; Class 2: G. mosseae; Class 3: Untreated control

Glass house experiment

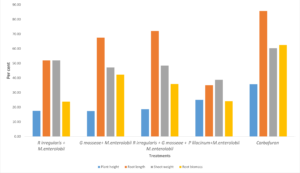

Plants inoculated with R. irregularis and G. mosseae exhibited significantly greater plant height, root length, and root and shoot weights compared to the control plants.

Mycorrhizal plants showed greater plant height and root length compared to non-mycorrhizal plants. Non-mycorrhizal plants inoculated with nematodes exhibited reduced growth parameters compared to the uninoculated control. The combined application of R. irregularis and G. mosseae showed no significant difference compared to individual applications of either R. irregularis or G. mosseae. Plant height and root length increased by 18.63% and 72.8%, respectively, relative to the control (Figure 7).

R. irregularis and G. mosseae significantly decreased the number of galls on guava roots, as well as the number of females (2.3) and egg masses (0.92) in the roots (Table 3). Mycorrhiza-treated plants exhibited a significantly lower nematode population in the soil compared to non-mycorrhizal plants. The combined application of R. irregularis and G. mosseae showed no notable difference compared to their applications. The lowest reproduction factor was recorded at 0.126, compared to 1.22 in the control (Table 4).

Table (3):

Effect of AM Fungi on plant growth parameters of Guava

Treatment |

Plant height (cm) |

Root length (cm) |

No of leaves |

Shoot weight (g) |

Root biomass (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

M. enterolobii alone |

46.7 |

15.4 |

18 |

22.7 |

8.28 |

R. irregularis + M. enterolobii |

56.6 |

23.4 |

21 |

34.5 |

10.25 |

G. mosseae+ M. enterolobii |

54.8 |

25.8 |

24 |

33.4 |

11.78 |

R irregularis + G. mosseae + M.enterolobii |

55.4 |

26.5 |

28 |

33.7 |

11.25 |

P. lilacinum+M. enterolobii |

58.4 |

20.8 |

24 |

31.5 |

10.28 |

Carbofuran 3G@ 1 kg a.i./ha |

63.4 |

28.6 |

26 |

36.4 |

13.46 |

SE.d |

0.34 |

1.12 |

NS |

0.27 |

0.71 |

C.D |

1.24 |

3.64 |

NS |

1.04 |

1.42 |

*Figures in parenthesis are log transformed values

Table (4):

Effect of AM Fungi on the population M. enterolobii in Guava

| Treatment | Number of galls/ 5 g root | No. Female/5 g root | Number of egg masses | Infective juvenile soil population/200 cc | Gall index | Reproduction factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | ||||||

| M. enterolobii alone | 43.5 | 10.4 | 8.4 | 432 | 531 | 5 | 1.2291 |

| R. irregularis + M. enterolobii | 7.2 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 421 | 58 | 2 | 0.1377 |

| G. mosseae + M. enterolobii | 7.8 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 412 | 52 | 2 | 0.1262 |

| R. irregularis + G. mosseae + M. enterolobii | 6.3 | 2.3 | 0.92 | 426 | 54 | 2 | 0.1267 |

| P. lilacinum + M. enterolobii | 12.8 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 442 | 62 | 3 | 0.1402 |

| Carbofuran 3G@ 1 kg a.i./ha | 2.1 | 1.2 | 0.73 | 451 | 12 | 1 | 0.0266 |

| SE.d | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.31 | NS | 1.1 | ||

| C.D | 2.34 | 1.8 | 0.93 | NS | 4.3 | ||

*Figures in parenthesis are log transformed values

Table (5):

Effect of AM Fungi on colonization, spore and enzyme activity in soil

Treatment |

Dehydrogenase (nmol TPF g-1 h-1) |

Spore count (50/g soil)* |

Total colonization (%)* |

Glomalin (mg glomalin/g soil)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

M. enterolobii alone |

1.12 |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

R. irregularis + M. enterolobii |

60.85 |

260 (2.41) |

92 (73.57) |

0.642 (0.21) |

G. mosseae+ M. enterolobii |

61.2 |

250 (2.39) |

90 (71.5) |

1.214 (0.34) |

R. irregularis + G. mosseae + M. enterolobii |

59.7 |

285 (2.45) |

95 (77.08) |

1.044 (0.31) |

P. lilacinum+ M. enterolobii |

22.2 |

1 (0.000) |

0 (0.00) |

1 (0.000) |

Carbofuran 3G@ 1 kg a.i./ha |

10.43 |

1 (0.000) |

0 (0.000) |

1 (0.000) |

SE.d |

0.92 |

0.072 |

NS |

0.051 |

C.D |

4.38 |

0.14 |

NS |

0.17 |

*Figures in parenthesis are Arcsine transformed values

Plants treated with mycorrhiza exhibited increased dehydrogenase activity (61.2 nmol TPF g-1 h-1) and glomalin production (1.214 g). The combined application of R. irregularis and G. mosseae resulted in the highest colonization percentage (95%) in guava plants (Table 5).

The root-knot nematode M. enterolobii has become a significant plant-parasitic nematode, severely impacting guava production. While synthetic chemicals effectively reduce nematode populations, their long-term consequences must be considered. As an alternative approach, genetic resistance techniques have been identified as effective in conferring resistance against M. enterolobii. This study examined the relationship between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and guava plants’ root-knot nematode M. enterolobii. Inoculation with the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi G. mosseae and R. irregularis significantly reduced nematode penetration and enhanced plant resilience-improving biomass, nutrient uptake, and stress-tolerance under adverse conditions.

Our findings revealed that the twin-chamber assay indicates that plant-nematode interactions are highly intricate, driven by the recognition of elicitors that guide nematodes to their host plants. Root exudates play a critical role in this process, serving as chemical signals that either attract,27 repel, or immobilize plant-parasitic nematodes, directing them toward optimal penetration sites on the roots.28 Schouteden et al.29 demonstrated that arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi modify rhizosphere interactions and trigger systemic resistance in plants, which influences nematode behavior and decreases plant vulnerability to nematode infection. Moreover, molecular techniques have elucidated the roles of nematode effectors and plant resistance mechanisms, revealing novel approaches for managing nematode infestations.30 AMF colonization in plant roots suppresses nematodes’ detection of elicitors, while the secondary metabolites produced disrupt nematode sensory perception, altering their behavior and impairing their ability to locate hosts.31 The interaction between AMF and plant roots significantly shapes the rhizosphere’s chemical environment, modulating nematode behavior and decreasing plant vulnerability to infection.32 The simultaneous presence of AMF and nematodes can lead to a synergistic detrimental impact on nematodes.33 AMF hinder the development of sedentary endoparasitic nematodes, compete with them for root infection sites and photosynthetic resources,34 and trigger plant defense mechanisms that negatively affect nematode survival and reproduction.35

AMF indirectly influence nematode populations by modifying the rhizosphere microbial community, promoting beneficial microorganisms like plant growth-promoting bacteria that antagonize nematodes.36 AMF colonization alters root exudate composition, affecting nematode behavior and survival through the production of antagonistic compounds such as phenylalanine, serine, and phenols.37 Additionally, AMF-induced changes in root cell wall composition and activation of plant defense mechanisms reduce nematode penetration.38

In our current study, nematodes exhibited reduced host-finding ability in AMF-treated plants compared to non-mycorrhizal plants, with a 55% decrease in attraction to the host. Beyond suppressing nematodes, AMF also induce plant growth and soil health by improving nutrient and water uptake, thereby boosting plant biomass and productivity. Furthermore, AMF supports soil aggregation and organic matter decomposition, improving soil structure and fertility.

Our study found that root exudates from plants colonized by R. irregularis and G. mosseae completely inhibited egg hatching at a 1% concentration, preventing the emergence of juvenile nematodes and significantly reducing egg hatching rates. Specifically, exudates from G. mosseae-treated plants reduced egg hatching. The results were on par with39-42 G. mosseae-treated plants significantly reduce nematode population and increase plant growth. Similarly, R. irregularis induced plant growth and reduced nematode populations.43-46 Research indicates that both quantitative and qualitative changes in root exudates from mycorrhizal plants can influence pathogen infection.47,48 These alterations in exudate composition also modify the rhizosphere microbial community, potentially exerting antagonistic effects on nematodes. Root exudates from mycorrhizal plants attract plant growth-promoting bacteria, such as Pseudomonas fluorescens,49 and foster populations of beneficial soil microorganisms.

AMF colonization impacted soil microbial activity, evidenced by increased dehydrogenase activity, soil respiration, and glomalin production, which in turn reduced nematode interactions. Elevated dehydrogenase activity in the G. mosseae treatment indicates higher hyphal production, enhancing microbial activity and decreasing nematode competition.50,51

The PCA from treatments with G. mosseae and or R. irregularis with single or two pathogens. A total of 99.6% (PC1 = 52.9%; PC2 = 46.7%) of the variation of the data was obtained. The result is on par with those reported in previous studies.52 Among the 50 identified compounds in root exudates, 21 were unique to AMF-inoculated plants, while the remaining 29 encompassed various classes, including alkanes, benzenoid derivatives, stilbenes, acids and their derivatives, phthalate esters, naphthalenes, and glycerolipids. Heat map analysis indicated that compounds such as octadecanoic acid, heptacosane, acetic acid, and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol were significantly upregulated in plants inoculated with R. irregularis. Similarly, dodecyl acrylate, acetic acid, and trilinolein were predominantly detected in G. mosseae-inoculated plants. The results were on par with Cai et al.53 These results suggest that AMF inoculation enhances the production of fatty acids, carboxylic acids, and benzoic acid derivatives in root exudates, which likely contribute to inhibiting nematode egg hatching and reducing juvenile attraction to roots, thereby improving control of M. enterolobii in tomato plants.

Guava plants colonized by AMF exhibited reduced susceptibility to nematodes and improved tolerance to parasitic infection. AMF mitigates nematode-induced damage by enhancing the host plant’s defense responses, enabling better endurance against infection. Inoculation with AMF in Meloidogyne-infected plants significantly boosts nutrient uptake, plant growth, and secondary metabolite production, leading to higher yields. These benefits persist under field conditions across multiple cropping cycles. Additionally, AMF triggers complex physiological changes in plants, including the activation of defense enzymes, production of nematicidal compounds, lignification of root tissues, and modifications in cell wall composition. These changes decrease nematode attraction and impede their ability to penetrate and infect roots.

Our research showed that inoculating plants with AMF, specifically G. mosseae and R. irregularis, significantly enhanced the length and weight of both vegetative plant parts and roots. Al-Huqail et al.54 demonstrated that co-inoculation with R. irregularis and Azospirillum brasilense enhanced plant growth, biomass, gas exchange properties, and the production of enzymatic and non-enzymatic compounds, along with their gene expression, while reducing oxidative stress. The results were on par with.39,55,56 AM fungi effectively counteracted the adverse impacts of pathogenic fungi on shoot and root growth. Multiple studies confirm that AM fungi colonization markedly boosts plant growth, primarily due to improved nutrient and water uptake, modified hormonal balance, and enhanced photosynthetic activity, all contributing to greater plant biomass.

AM fungi boost plant resistance by enhancing nutrient absorption, especially phosphorus, and regulating plant defense mechanisms, which in turn reduces nematode reproduction and associated damage. R. irregularis and G. mosseae demonstrate different levels of efficacy in reducing nematode populations. Our findings highlight the potential of G. mosseae and R. irregularis as a sustainable and environmentally friendly strategy for managing M. enterolobii populations in the guava ecosystem. Future studies should concentrate on refining AMF inoculation methods, investigating synergistic effects with other biocontrol agents, and incorporating AMF-based strategies into sustainable farming practices. Advances in molecular techniques can further clarify the specific mechanisms behind AMF-mediated nematode suppression, facilitating targeted approaches for nematode management.

Additional file: Table S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All authors gratefully acknowledge the Department of Plant Protection, Horticultural College and Research Institute, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Periyakulam, and the Department of Agricultural Microbiology, Tamil Nadu, Coimbatore, India.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analysed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Arevalo-Marin E, Casas A, Landrum L, et al. The taming of Psidium guajava: Natural and cultural history of a neotropical fruit. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:714763.

Crossref - Nagachandrabose S, Rajendran P, Ganeshan S, et al. Resistance to Meloidogyne enterolobii in guava: Screening of cultivated and wild types, resistance principles, and graft compatibility. Sci Hort. 2024;338:113825.

Crossref - Castagnone-Sereno P. Meloidogyne enterolobii (= M. mayaguensis): profile of an emerging, highly pathogenic, root-knot nematode species. Nematology. 2012;14(2):133-138.

Crossref - Jones JT, Haegeman A, Danchin EGJ, et al. Top 10 plant parasitic nematodes in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol. 2013;14(9):946-961.

Crossref - Singh J. Nematodal Diseases of Guava: Effective Control and Management. Agri roots. 2024;2(8):5-8. https://www.agrirootsmagazine.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/ARTICLE-ID-0118.pdf

- Tiwari S. Impact of nematicides on plant-parasitic nematodes: Challenges and environmental safety. Tunis J Plant Prot. 2024;19(2).

Crossref - Wahab A, Muhammad M, Munir A, et al. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in regulating growth, enhancing productivity, and potentially influencing ecosystems under abiotic and biotic stresses. Plants. 2023;12(17):3102.

Crossref - Ngosong C, Tatah BN, Olougou MNE, et al. Inoculating plant growth-promoting bacteria and arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi modulates rhizosphere acid phosphatase and nodulation activities and enhance the productivity of soybean (Glycine max). Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:934339.

Crossref - Sangwan S, Prasanna R. Mycorrhizae helper bacteria: unlocking their potential as bioenhancers of plant-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal associations. Microb Ecol. 2022;84(1):1-10.

Crossref - Wang F, Zhang L, Zhou J, Rengel Z, George TS, Feng G. Exploring the secrets of hyphosphere of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: processes and ecological functions. Plant Soil. 2022;481(1):1-22.

Crossref - Edlinger A, Garland G, Hartman K, et al. Agricultural management and pesticide use reduce the functioning of beneficial plant symbionts. Nat Ecol Evol. 2022;6(8):1145-1154.

Crossref - De Sa CSB, Campos MAS. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi decrease Meloidogyne enterolobii infection of Guava seedlings. J Helminthol. 2020;94:e183.

Crossref - Vos C, Geerinckx K, Mkandawire R, Panis B, De Waele D, Elsen A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi affect both penetration and further life stage development of root-knot nematodes in tomato. Mycorrhiza. 2012;22:157-163.

Crossref - Elsen A, Gervacio D, Swennen R, De Waele D. AMF-induced biocontrol against plant parasitic nematodes in Musa sp.: a systemic effect. Mycorrhiza. 2008;18(5):251-256.

Crossref - Vallejos-Torres G, Espinoza E, Marin-Diaz J, Solis R, Arevalo LA. The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi against root-knot nematode infections in coffee plants. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2021;21(1):364-373.

Crossref - da Silva Campos MA. Applications of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Controlling Root-Knot Nematodes. In: Ahammed GJ, Hajiboland R. (eds) Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Higher Plants. Springer, Singapore. 2024:225-237.

Crossref - Yurkov AP, Kryukov AA, Gorbunova AO, et al. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in distinct ecosystems of the North Caucasus, a temperate biodiversity hotspot. J Fungi. 2023;10(1):11.

Crossref - Liu X, Ye G, Feng Z, et al. Cold storage promotes germination and colonization of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal hyphae as propagules. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1450829.

Crossref - Henry A, Doucette W, Norton J, Bugbee B. Changes in crested wheatgrass root exudation caused by flood, drought, and nutrient stress. J Environ Qual. 2007;36(3):904-912.

Crossref - Vierheilig H, Lerat S, Piche Y. Systemic inhibition of arbuscular mycorrhiza development by root exudates of cucumber plants colonized by Glomus mosseae. Mycorrhiza. 2003;13(3):167-170.

Crossref - Speijer PR, de Waele D. Screening of Musa Germplasm for Resistance and Tolerance to Nematodes. INIBAP Technical Guidelines 1. Montpellier, France: International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plantain; 1997.

- Pang Z, Chong J, Zhou G, et al. MetaboAnalyst 5.0: narrowing the gap between raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(W1):W388-W396.

Crossref - Gerdemann J, Nicolson TH. Spores of mycorrhizal Endogone species extracted from soil by wet sieving & decanting. Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 1963;46(2):235-244.

Crossref - Casida Jr LE, Klein DA, Santoro T. Soil dehydrogenase activity. Soil Science. 1964;98(6):371-376.

Crossref - Schindler AR, Stewart RN, Semeniuk P. A synergistic Fusarium-nematode interaction in carnation. Phytopathology. 1961;51(3):143-146.

- Heald CM, Bruton BD, Davis RM. Influence of Glomus intraradices and soil phosphorus on Meloidogyne incognita infecting Cucumis melo. J Nematol. 1989;21(1):69-73.

- Curtis RHC, Robinson AF, Perry RN. Hatch and host location. Root-knot nematodes. CABI Wallingford UK. 2009:139-162.

Crossref - Koltai H, Dhandaydham M, Opperman C, Thomas J, Bird D. Overlapping plant signal transduction pathways induced by a parasitic nematode and a rhizobial endosymbiont. Mol Plant Microb Interact. 2001;14(10):1168-1177.

Crossref - Schouteden N, De Waele D, Panis B, Vos CM. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for the biocontrol of plant-parasitic nematodes: a review of the mechanisms involved. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1280.

Crossref - Abd-Elgawad MMM. Understanding molecular plant-nematode interactions to develop alternative approaches for nematode control. Plants. 2022;11(16):2141.

Crossref - Holbein J, Franke RB, Marhavy P, et al. Root endodermal barrier system contributes to defence against plant parasitic cyst and root knot nematodes. Plant J. 2019;100(2):221-236.

Crossref - Tahat MM, Sijam K. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant root exudates bio-communications in the rhizosphere. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2012;6(46):7295-7301.

Crossref - Sharma IP, Sharma AK. Co-inoculation of tomato with an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus improves plant immunity and reduces root-knot nematode infection. Rhizosphere. 2017;4:25-28.

Crossref - Aseel DG, Rashad YM, Hammad SM. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi trigger transcriptional expression of flavonoid and chlorogenic acid biosynthetic pathways genes in tomato against Tomato Mosaic Virus. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):9692.

Crossref - Dababat AE-FA, Sikora RA. Influence of the mutualistic endophyte Fusarium oxysporum 162 on Meloidogyne incognita attraction and invasion. Nematology. 2007;9(6):771-776.

Crossref - Srinivas C, Devi DN, Murthy KN, et al. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici causal agent of vascular wilt disease of tomato: Biology to diversity–A review. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2019;26(7):1315-1324.

- Siddiqui ZA, Mahmood I. Some observations on the management of the wilt disease complex of pigeonpea by treatment with a vesicular arbuscular fungus and biocontrol agents for nematodes. Bioresource Technology. 1995;54(3):227-230.

Crossref - Azcon-Aguilar C, Barea J. Arbuscular mycorrhizas and biological control of soil-borne plant pathogens-an overview of the mechanisms involved. Mycorrhiza. 1997;6:457-464.

Crossref - Odeyemi IS, Afolami SO, Sosanya OS. Effect of Glomus mosseae (arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus) on host-parasite relationship of Meloidogyne incognita (Southern root-knot nematode) on four improved cowpea varieties. J Plant Protect Res. 2010;50(3).

Crossref - Van der Veken L, Cabasan MTN, Elsen A, Swennen R, De Waele D. Effect of single or dual inoculation of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus mosseae and root-nodulating rhizobacteria on reproduction of the burrowing nematode Radopholus similis on non-leguminous and leguminous banana intercrops. J Plant Dis Protect. 2021;128:961-971.

Crossref - Robab MI, Shaikh H, Azam T. Antagonistic effect of Glomus mosseae on the pathogenicity of root-knot nematode infected Solanum nigrum. Crop Protect. 2012;42:351-355.

Crossref - Sohrabi F, Fadaei-Tehrani A, Danesh YR, Jamali-Zavareh A. Study on Interaction between two arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomus mosseae and Glomus intraradices) and root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne javanica) in tomato. 2012. Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 2012;48(3):393-401

- Yavuzaslanolu E, Aksay G, Delen B, Cetinkaya A. The interaction of the mycorrhizae of the fungus Rhizophagus irregularis (Walker & Sch ler, 2010)(Glomerales: Glomeraceae) and the stem and bulb nematode (Ditylenchus dipsaci K hn, 1857)(Tylenchida: Anguinidae) on the onion plant (Allium cepa L.)(Asparagales: Amaryllidaceae). Turkiye Biyolojik Mucadele Dergisi. 2021;12(2):120-129.

Crossref - Ahamad L, Siddiqui ZA, Hashem A, Abd_Allah EF. Use of AM fungus Rhizophagus irregularis and silicon dioxide nanoparticles for the management of Meloidogyne incognita, Alternaria dauci and Rhizoctonia solani and growth of carrot. Arch Phytopathol Plant Protect. 2023;56(6):466-488.

Crossref - Zoubi B, Mokrini F, Houssayni S, et al. Effectiveness of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi Funneliformis mossae and Rhizophagus irregularis as biological control agent of the citrus nematode Tylenchulus semipenetrans. Journal of Natural Pesticide Research. 2025;11:100104.

Crossref - Sedhupathi K, Kennedy ZJ, Shanthi A. Interaction of arbuscular fungus (Rhizophagus irregularis), Bacillus subtilis and Purpureocillium lilacinum against root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) in tomato. Indian J Nematol. 2022;52(1):92-103.

Crossref - Hodge A. Microbial ecology of the arbuscular mycorrhiza. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2000;32(2):91-96.

Crossref - Jones DL, Hodge A, Kuzyakov Y. Plant and mycorrhizal regulation of rhizodeposition. New Phytologist. 2004;163(3):459-480.

Crossref - Gupta Sood S. Chemotactic response of plant-growth-promoting bacteria towards roots of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal tomato plants. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2003;45(3):219-227.

Crossref - Fernandes SAP, Bettiol W, Cerri CC. Effect of sewage sludge on microbial biomass, basal respiration, metabolic quotient and soil enzymatic activity. Appl Soil Ecol. 2005;30(1):65-77.

Crossref - Gianfreda L, Rao MA, Piotrowska A, Palumbo G, Colombo C. Soil enzyme activities as affected by anthropogenic alterations: intensive agricultural practices and organic pollution. Sci Total Environ. 2005;341(1-3):265-279.

Crossref - Ahamad L, Siddiqui ZA. Effects of Pseudomonas putida and Rhizophagus irregularis alone and in combination on growth, chlorophyll, carotenoid content and disease complex of carrot. Indian Phytopathol. 2021;74(3):763-773.

Crossref - Cai X, Zhao H, Liang C, Li M, Liu R. Effects and mechanisms of symbiotic microbial combination agents to control tomato fusarium crown and root rot disease. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:629793.

Crossref - AL-Huqail AA, Alatawi A, Javed S, et al. Individual and Combinatorial Applications of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Increase Morpho-Physio-Biochemical Responses in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) under Cadmium Stress. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2025;25(68):1-19.

Crossref - Sankaranarayanan C, Hari K. Integration of arbuscular mycorrhizal and nematode antagonistic fungi for the biocontrol of root lesion nematode Pratylenchus zeae Graham, 1951 on sugarcane. Sugar Tech. 2021;23(1):194-200.

Crossref - Talavera M, Itou K, Mizukubo T. Reduction of nematode damage by root colonization with arbuscular mycorrhiza (Glomus spp.) in tomato-Meloidogyne incognita (Tylenchida: Meloidogynidae) and carrot-Pratylenchus penetrans (Tylenchida: Pratylenchidae) pathosystems. Appl Entomol Zool. 2001;36(3):387-392.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.