Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a leading cause of persistent and severe lung infections, especially in individuals with weakened immune systems and those suffering from conditions like cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis. The pathogen’s resistance to antibiotics, driven by its ability to form biofilms, activate efflux pumps, and produce enzymes that break down drugs, has significantly limited the effectiveness of standard antimicrobial therapies. This review explores the increasing promise of bacteriophage therapy as both an alternative and a complementary approach for addressing multidrug-resistant (MDR) P. aeruginosa infections in the lungs. Phages, viruses that specifically target bacteria, offer strain-specific bactericidal activity, often bypassing mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Recent studies demonstrate that phage monotherapy and phage-antibiotic combinations can effectively disrupt biofilms and enhance bacterial clearance, particularly when phage cocktails or targeted delivery systems are employed. Additionally, the review explores delivery routes for pulmonary infections and the formulation challenges that affect phage stability and bioavailability. Clinical cases and ongoing trials further underscore the feasibility and safety of phage therapy in real-world applications. However, hurdles such as phage immunogenicity, rapid clearance, and regulatory limitations must be addressed before widespread clinical implementation. Overall, phage therapy holds significant promise in overcoming the therapeutic stagnation posed by MDR P. aeruginosa, especially in chronic and nosocomial lung infections, and warrants continued research and clinical validation.

Phage-antibiotic Combination, Antibiotic Resistance, Biofilm, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Lung infections remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with death rates ranging between 20% and 50%, depending on healthcare quality and access.1 In North America, Pseudomonas aeruginosa–associated chronic lung infections account for up to 20% of fatalities, while Europe reports rates of 15%-25%.2 In developing regions such as Africa and Southeast Asia, mortality exceeds 30% due to limited treatment access and widespread antibiotic resistance.3 Severe cases often progress to respiratory failure or sepsis.4 Conventional treatment relies on antibiotics such as beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones. However, the success of these drugs is hindered by P. aeruginosa’s robust resistance mechanisms, including beta-lactamase production, target-site modification, and active efflux systems.5,6 These features often lead to persistent infections and relapse despite therapy.7,8

The pathogen’s ability to form biofilms further complicates management. Within these structured microbial communities, bacteria are shielded by an extracellular matrix that limits antibiotic penetration and immune recognition.9 Biofilm-associated P. aeruginosa exhibits up to 1,000-fold higher antibiotic resistance than planktonic cells, particularly in patients with cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis.10-15 Bacteriophages, viruses that specifically infect bacteria, present a promising alternative. They are natural bacterial predators that have long been studied for their antimicrobial potential.16 Beyond their ecological roles, phages have been applied in human therapy, food safety, and biotechnology.17,18 Phage therapy exploits their ability to selectively lyse bacterial pathogens, providing a targeted strategy against antibiotic-resistant P. aeruginosa without disturbing the host microbiota.19,20 This review discusses the therapeutic potential of bacteriophages in treating P. aeruginosa–induced lung infections, emphasizing their role as alternative or adjunct agents in overcoming antibiotic resistance and biofilm-associated persistence.

Bacteriophages

Bacteriophages are broadly categorized into two types based on their replication cycles: virulent and temperate. Virulent phages undergo the lytic cycle, infecting bacterial cells and synthesizing proteins that disrupt key cellular processes such as DNA replication, transcription, and translation. These proteins degrade the host genome, hijack bacterial enzymes, and compromise cell membrane integrity, culminating in host lysis and the release of progeny phages.21 In contrast, temperate phages can alternate between the lytic and lysogenic cycles. During lysogeny, the phage genome integrates into the host chromosome as a prophage, conferring immunity to reinfection through repressor proteins and, in some cases, enhancing bacterial virulence via horizontal gene transfer.22

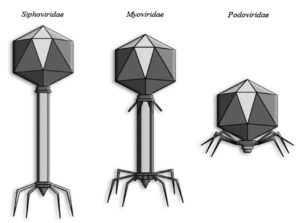

The lytic cycle comprises four essential stages: adsorption, penetration, intracellular replication, and release. The process begins with phage attachment to specific bacterial surface receptors, followed by injection of phage DNA. The host’s machinery is then reprogrammed to produce viral components, which assemble into mature virions that burst the host cell to release new infectious particles.23 Clinically relevant phages largely belong to the order Caudovirales, characterized by double-stranded DNA genomes and tailed morphologies. These phages possess an icosahedral capsid and a tail equipped with receptor-binding proteins for host recognition and genome delivery.24 Based on tail structure, Caudovirales are divided into three families: Siphoviridae (long, flexible, noncontractile tails), Myoviridae (long, contractile tails), and Podoviridae (short, noncontractile tails).25

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

P. aeruginosa is a Gram-negative, aerobic, rod-shaped bacterium (0.5-3.0 µm) commonly found in moist environments such as swimming pools, hot tubs, hospital humidifiers, and medical devices like catheters.26 Although capable of infecting healthy individuals, it primarily acts as an opportunistic pathogen, responsible for both community-acquired infections—such as folliculitis, otitis externa, and pneumonia—and a large proportion of hospital-acquired infections. A key diagnostic feature of P. aeruginosa is its non-fermentative metabolism, as it does not produce acidic byproducts under anaerobic conditions. This is confirmed by the oxidative–fermentative (OF) test, which indicates oxidative metabolism restricted to aerobic environments. Structurally, the bacterium possesses a single polar flagellum and Type IV pili, which facilitate swimming and twitching motility, respectively. These organelles are critical for adhesion, surface colonization, and biofilm formation, enabling P. aeruginosa to persist on biotic and abiotic surfaces while evading host immune defenses (Figure 1).27

Clinical Significance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

The virulence of P. aeruginosa stems from a wide array of pathogenic mechanisms, including the production of hemolytic agents like Rhamnolipid and Phospholipase C, which disrupt host cell membranes and degrade pulmonary surfactants, factors that contribute to lung tissue damage and the establishment of chronic respiratory infections.28,29 Within the airways, P. aeruginosa impairs mucociliary function and weakens local immune defenses, facilitating long-term colonization. One of its most adaptive traits is its ability to form biofilms, highly organized bacterial communities surrounded by a protective extracellular matrix.30 These structures not only shield the bacteria from antibiotics and host immune cells but also interfere with neutrophil activity. Additionally, virulence enzymes such as Elastase and Alkaline protease degrade key immune components including immunoglobulins, cytokines like IL-1 and TNF, and complement proteins, undermining both innate and adaptive responses. The surface protein Lpd contributes to immune evasion by binding Factor H, thereby inhibiting the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) and enhancing serum resistance.31,32 Certain strains have also been shown to dampen inflammasome signaling and reduce the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and IL-18, particularly in chronic conditions such as cystic fibrosis.4

P. aeruginosa utilizes quorum sensing, a population-density-dependent signaling mechanism—to regulate the production of various virulence factors, including Elastase, Pyocyanin, Rhamnolipids, and Exotoxin A (ExoA). ExoA disrupts host protein synthesis by ADP-ribosylating elongation factor-2, while Elastase and Phospholipase C facilitate tissue invasion and help the bacterium evade immune detection. Another critical virulence system is the Type III secretion system (T3SS), which directly injects effector proteins into host cells, leading to cytoskeletal disruption, impaired phagocytosis, and cell death. The presence of genes encoding either exoU or exoS determines the pathogenic behavior of clinical isolates.4,27 The outer membrane component Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) interacts with host immune receptors, particularly Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), triggering inflammatory responses. Variations in LPS structure help the bacterium evade immune detection and also make it a promising candidate for vaccine development. In chronic respiratory infections, especially in cystic fibrosis. P. aeruginosa often adopts a mucoid phenotype, characterized by the overproduction of alginate, a sticky exopolysaccharide that strengthens biofilm formation and promotes adhesion. Furthermore, the bacterium releases siderophores such as pyoverdine and pyochelin to acquire iron from the host environment, a critical factor for its survival. These iron-scavenging molecules are highly immunogenic and are being explored as vaccine targets.33,34

In healthcare settings, P. aeruginosa is a leading cause of both ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), with MDR and carbapenem-resistant strains (CR-PA) posing a significant threat, particularly in intensive care units (ICUs). In the United States, it is the sixth most frequently identified pathogen in hospital-acquired infections and ranks second in cases of VAP.35 The emergence of carbapenem resistance is a global concern, with research from countries such as Nigeria and Brazil reporting a high prevalence of MDR P. aeruginosa isolates in ICU environments.36,37 Outside of acute nosocomial infections, P. aeruginosa plays a central role in chronic respiratory diseases. It affects more than 75% of individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF), contributing to progressive lung damage, respiratory failure, and increased mortality.33 Similarly, in patients with bronchiectasis, infections caused by this organism are linked to more rapid lung function decline and a threefold rise in mortality risk.38

Challenges with conventional Antibiotics

The extensive use of antibiotics in human medicine, veterinary care, and agriculture has significantly contributed to the emergence of MDR pathogens, representing a serious and escalating global health crisis.39,40 Hospital-acquired infections involving MDR organisms further intensify this threat to public health. Meanwhile, the discovery and development of new antibiotics have not kept pace with the rise of resistance, leaving healthcare systems increasingly vulnerable.41 In the United States alone, MDR pathogens are responsible for approximately 2.8 million infections and 35,000 deaths annually, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).42,43 The World Health Organization (WHO) projects that by 2050, MDR infections could result in up to 10 million deaths globally each year.44 The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics can also lead to superinfections by disrupting the host’s normal microbial flora, facilitating conditions such as Clostridium difficile colitis or Candida albicans overgrowth.45,46 Additionally, certain antibiotics—such as tetracyclines, macrolides, and chloramphenicol—are classified as bacteriostatic agents. These drugs inhibit bacterial growth rather than directly killing the pathogens. Unlike bactericidal antibiotics, bacteriostatic agents may prolong bacterial survival, giving microbes more time to adapt and potentially develop resistance.47,48

Cross-resistance with antibiotics is a condition in which the bacteria are resistant to multiple antibiotics, even with a single resistance mechanism. The resistance can be within the same class due to similar structural targets or even across different structures because of overlapping mechanisms of action. The best example of cross-resistance is Staphylococcus aureus strain, which becomes resistant to erythromycin, clindamycin, and Streptogramin B antibiotics, because of acquiring an erm gene, even though the drugs are structurally different.49-51 Microorganisms form biofilms with the aid of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), particularly on medical devices such as catheters and prosthetic implants. These biofilms act as physical barriers and create altered microenvironments that significantly reduce the effectiveness of antibiotics. For example, P. aeruginosa in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients demonstrates resistance to tobramycin due to its ability to form protective biofilms.52,53 In addition, research from India and other countries highlights the alarming presence of antibiotic residues in animal-derived food products and elevated concentrations of antibiotics in wastewater. These environmental factors further accelerate the spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).54-56

Phage Delivery

Phage Administration

The primary objective of delivering bacteriophages to an infection site is to achieve an adequate concentration of viable phage particles capable of lysing the target bacteria and replicating to reach inundative phage densities. To this end, various routes of administration have been investigated, tailored to the specific infection site. These can be broadly categorized into topical (e.g., direct application, inhalation, nebulization, and transdermal delivery), parenteral (e.g., intramuscular, intravenous, and subcutaneous), and oral routes.57-59 A comprehensive understanding of each delivery method is essential for effective therapeutic outcomes. Among these, topical administration presents certain advantages, as it circumvents systemic absorption and distribution barriers, resulting in higher localized phage concentrations. This approach has been effectively utilized in managing skin burns, wounds, superficial bacterial infections, and respiratory infections.

Parenteral administration, especially through intravenous injection, is regarded as one of the most effective delivery methods for bacteriophages due to its ability to ensure rapid systemic distribution. However, this route is often limited by a significant decline in phage concentration, primarily due to rapid clearance by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) and elimination by immune responses.60-62 In contrast, oral administration is the most convenient, minimally invasive, and cost-effective approach. Despite these advantages, its therapeutic efficacy is frequently reduced due to phage degradation in the acidic gastric environment and losses during gastrointestinal absorption.63 To address these limitations, several protective strategies have been developed. These include encapsulation techniques using biocompatible materials such as polysaccharides, alginate–caseinate and alginate–whey protein combinations, and chitosan, all of which have demonstrated encouraging outcomes in preserving phage viability.64,65

In cases of pulmonary infections, several delivery approaches have been explored, including inhalation via nebulization, endotracheal administration, and direct instillation through bronchoscopy—either individually or in combination.59,61 Direct pulmonary administration through nebulized liquid phage or inhalable dry powder formulations has demonstrated effectiveness, offered the benefit of high local phage concentrations while bypassed nasal barriers.66,67 Recent advancements in nebulization technology have significantly enhanced the application of phage therapy for respiratory infections. Various aerosol generation methods are now employed, including compressed air jet, ultrasonic, vibrating mesh and colliding liquid jets. Comparative analyses of these techniques—performed independently across different phage types—have assessed critical parameters such as delivery efficiency, reduction in phage titer, and structural integrity. These studies suggest that the optimal method depends on the specific phage employed and its tolerance to mechanical stress during nebulization.68,69 Importantly, there is no universal nebulization method applicable to all phages. Each phage type requires individualized assessment of its structural and functional resilience during aerosolization. This consideration is particularly crucial when using phage cocktails, as post-nebulization recovery and viability have been shown to correlate with morphological characteristics, such as tail length.70

Phage stability and formulation strategies

Bacteriophages are composed of a proteinaceous capsid that encloses their genetic material, either DNA or RNA. Despite their therapeutic potential, phages are inherently sensitive to various environmental and physiological stressors, including pH fluctuations, oxidative conditions, enzymatic degradation, immune responses, and mechanical shear forces during aerosol generation. To address these challenges, encapsulation strategies have been developed to enhance phage stability and efficacy.71 Encapsulation involves coating phages with biocompatible and biodegradable polymers such as polysaccharides, polyelectrolytes, dextran sulfate, and chitosan—materials favored for their non-toxic nature and protective properties.58,72 This protective matrix not only shields the phage from hostile environments but also ensures sustained release and preservation of infectivity, thereby maximizing therapeutic potential upon delivery to the target bacterial host.73 Another well-established formulation approach is the encapsulation of phages within liposomes—spherical vesicles composed of bioactive phospholipids enclosing an aqueous core that contains the phage. Liposome-encapsulated phages offer distinct advantages, including the ability to fuse with host cell membranes, facilitating intracellular delivery and enabling the targeting of intracellular pathogens.74 Moreover, this strategy enhances the intracellular accumulation of antibiotics when used in combination therapy, thereby increasing bacterial susceptibility and improving therapeutic outcomes.75

Phage against P. aeruginosa biofilm

P. aeruginosa is notorious for inflicting considerable tissue damage through various virulence factors, and its ability to persist in chronic infections is largely attributed to its capacity to form biofilms.76 The effectiveness of phage therapy against P. aeruginosa biofilms depends on the specific phages used. Research evaluating the activity of three different phages against MDR P. aeruginosa biofilms found that smaller phages may be more effective, as their higher surface area-to-volume ratio allows for improved penetration into the dense biofilm matrix, enhancing therapeutic outcomes.77 Additionally, the study suggested that phage cocktails—combinations of multiple phages, can produce a synergistic effect, potentially counteracting the bacterium’s adaptability.78 This implies that tailored phage cocktails targeting various components of the biofilm and bacterial population may represent a more effective therapeutic strategy.

Recent studies support the potential of phages to degrade P. aeruginosa biofilms effectively. Phages can disrupt biofilm formation by releasing enzymes that break down biofilm matrices, thus improving treatment outcomes. For example, isolated phage MA-1 from wastewater and demonstrated its stability under diverse environmental conditions, a critical factor for therapeutic applications.79 The efficacy of phage MA-1 was attributed to its impressive heat and pH stability, which is essential for addressing biofilms in fluctuating physiological environments.80 Moreover, phage therapy illustrated efficacy by employing a phage cocktail, CT-PA, which resulted in a median reduction of biofilm biomass by 76% within 48 hours of treatment, irrespective of the antimicrobial resistance profiles of the isolates.81 This underscores the advantage of phage cocktails over single phage therapies, as they can simultaneously target multiple strains and resistance mechanisms, thereby enhancing the likelihood of successful biofilm eradication.

Kim et al. characterized phage PA1Ø, a lytic phage with broad-spectrum bactericidal activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including P. aeruginosa. PA1Ø’s mechanism of action involves targeting Type IV pili, structures critical to biofilm formation and maintenance.82 This specificity underscores the therapeutic potential of phages that exploit essential bacterial features. Targeting such structures can enhance treatment precision and effectiveness, particularly in biofilm-associated infections. The combination of structure-targeted phages and phage cocktails represents a promising strategy in addressing antibiotic-resistant infections. In the context of chronic diseases involving biofilms, this approach strengthens the therapeutic utility of phage therapy. The efficacy of various phages against P. aeruginosa biofilms is summarized in Table, illustrating the potential of phage-based interventions in this complex clinical scenario.

Table:

Reported Biofilm Reduction Efficiencies of Phages Targeting Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Type of Phage |

Target Strain |

Efficacy on Biofilm |

Reduction Rate |

Specimen Type |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bacteriophage F8 |

P. aeruginosa |

Enhanced biofilm degradation |

Not specified |

in vitro |

(83) |

Bacteriophage MAC-1 |

P. aeruginosa |

Effective against planktonic cells and biofilms |

75% |

in vitro |

(84) |

Phage cocktail |

P. aeruginosa |

Significant reduction in biofilm formation |

80% |

in vitro |

(85) |

Novel phage |

Multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa |

High efficacy in biofilm eradication |

90% |

in vitro |

(86) |

Phage PH826 |

Multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa |

Synergistic effects with antibiotics |

70% |

in vitro |

(87) |

Various phages |

P. aeruginosa |

Effective in wound biofilm reduction |

85% |

in vitro |

(88) |

Lytic phage |

P. aeruginosa |

Strong antibiofilm activity |

95% |

in vivo |

(89 |

Phage Motto |

P. aeruginosa |

Effective in degrading biofilms |

88% |

Both |

(90) |

Various phages |

P. aeruginosa |

Varies; specific phage efficacy reported |

60%-80% (varied) |

in vitro |

(91) |

Various phages |

P. aeruginosa |

Generally effective across various infections |

70% |

Both |

(92) |

Bacteriophage cocktail |

P. aeruginosa |

Effective against dual species biofilms |

75% |

in vitro |

(93) |

Various phages |

P. aeruginosa |

Effective in controlling infectious biofilms |

Not specified |

Both |

(94) |

Bacteriophages + ZnO nanoparticles |

P. aeruginosa |

Effective in reducing biofilm formation |

78% |

in vitro |

(95) |

Lytic phage |

P. aeruginosa |

High antibiofilm efficacy |

85% |

in vitro |

(96) |

Various phages |

P. aeruginosa |

Effective against both planktonic and biofilm forms |

80% |

Both |

(97) |

Phage-antibiotic combination against P. aeruginosa lung infections

P. aeruginosa has become a central focus in phage–antibiotic combination (PAC) therapy research due to its involvement in severe infections such as cystic fibrosis, burn wound infections, and hospital-acquired pneumonia, as emphasized by Tagliaferri et al.98 The organism’s intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms against multiple antibiotic classes such as β-lactamase production, efflux pump activity, and biofilm formation, have rendered many standard treatments ineffective, necessitating the exploration of alternative or adjunctive therapeutic strategies. Santamaria-Corral et al.99 reviewed recent advances highlighting the synergistic potential of PAC therapy demonstrated through both in vitro and in vivo experiments, with several successful clinical case reports supporting these findings.

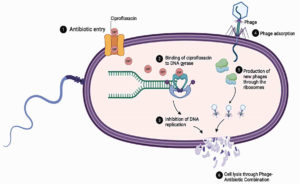

Experimental studies indicate that phage–antibiotic combinations enhance bacterial clearance across various drug classes, including aminoglycosides, β-lactams, macrolides, polymyxins, and tetracyclines.99 Among these, ciprofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone, has exhibited particularly high compatibility with phages. Chang et al. reported superior biofilm removal when phage PEV20 was administered alongside ciprofloxacin, while Lin et al. demonstrated in murine models that nebulized PEV20 combined with ciprofloxacin significantly improved bacterial eradication compared to monotherapies.100,101 These synergistic outcomes are attributed to complementary mechanisms: phage-mediated bacterial lysis disrupts the biofilm matrix, increasing antibiotic penetration, while subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics can sensitize bacteria to phage infection by modifying surface receptors and impairing DNA repair pathways. Moreover, antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin that inhibit DNA gyrase may indirectly favor phage replication by synchronizing host DNA metabolism with viral genome amplification. Together, these interactions accelerate bacterial killing and limit the emergence of resistant subpopulations, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Despite strong experimental evidence, PAC therapy outcomes are not universally synergistic. Antagonistic effects have been observed when antibiotic concentrations are too high or administered too early, reducing bacterial density before sufficient phage replication can occur. These variations underscore the importance of optimizing dosing regimens, treatment timing, and the selection of compatible phage–antibiotic pairs to achieve maximal synergy. The success of ciprofloxacin–phage combinations suggests that antibiotic mechanisms targeting DNA replication or cell-wall synthesis may be more conducive to synergy than those interfering with protein synthesis.

Clinical case studies have reinforced the translational potential of PAC therapy. Kohler et al.102 documented a rapid clinical recovery in a 41-year-old patient with Kartagener syndrome and chronic multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa infection following aerosolized phage vFB297 co-administered with antibiotics. Similarly, Chen et al.103 reported the successful resolution of infection in a 68-year-old patient with a broncho-pleural fistula after an 18-day course of intrapleural phage administration in combination with antibiotics. These findings support the feasibility and safety of phage–antibiotic co-therapy, particularly in biofilm-dominated pulmonary infections where conventional antibiotics often fail.

Several clinical trials further highlight the growing momentum of PAC therapy. The SWARM-Pa trial (NCT04596319), completed in 2022, demonstrated that inhaled phage AP-PA02 was well-tolerated in cystic fibrosis patients chronically infected with P. aeruginosa, meeting safety endpoints within 28 days.104 The WRAIR-PAM-CF1 trial (NCT05453578) is currently evaluating an inhaled phage cocktail for its efficacy in reducing bacterial burden and improving lung function, while the TAILWIND trial (NCT05616221) aims to assess pharmacokinetics, therapeutic performance, and safety parameters.105 Collectively, these ongoing efforts demonstrate increasing clinical validation of PAC therapy and its potential to complement or even enhance existing antibiotic regimens.

Nevertheless, several challenges remain before PAC therapy can be standardized for routine clinical use. Variability in phage pharmacokinetics, immune neutralization, and potential antagonism with certain antibiotics warrant further investigation. Moreover, regulatory frameworks, quality control in phage manufacturing, and patient-specific therapeutic customization still pose significant hurdles. Future research should focus on defining optimal dosing ratios, clarifying molecular synergy pathways, and developing computational models to predict phage–antibiotic interactions. Integrating these findings with precision-medicine approaches may ultimately enable PAC therapy to serve as a viable and sustainable strategy against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa infections.

P. aeruginosa continues to pose a major threat in lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs), especially among immunocompromised patients and those with chronic conditions like cystic fibrosis. Its persistence is largely due to its ability to form biofilms, develop multidrug resistance, and adapt rapidly to antimicrobial pressures, all of which complicate conventional treatment strategies. As the effectiveness of standard antibiotics diminishes, phage therapy has gained attention as a promising alternative, particularly in targeting biofilm-associated and drug-resistant P. aeruginosa. Both preclinical and clinical research have shown that combining bacteriophages with antibiotics can produce synergistic effects, leading to improved bacterial eradication in vitro and in vivo. However, several barriers must be addressed before widespread clinical adoption is feasible. Chief among these is the host immune response, which may neutralize bacteriophages and reduce therapeutic efficacy. Innate immune defenses such as phagocytic clearance and complement-mediated lysis, as well as adaptive responses involving anti-phage antibodies, present significant obstacles. Despite these immunological challenges, the growing body of evidence supports the use of phage-antibiotic combinations as a viable and forward-looking approach to managing P. aeruginosa infections. Continued advancements in phage engineering, delivery platforms, and immunomodulatory strategies will be critical to unlocking the full therapeutic potential of phage-based treatments and incorporating them into mainstream care for respiratory infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to NU Fairview Incorporated.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

JAGF conceptualized the study. JAGF, CKF, VS, JW and AM performed data curation. JAGF, CKF, VS, JW, JJCDR and AM performed data analysis. VS, JW, JJCDR, JAGF, CKF, JJMN and AM wrote the manuscript. JJMN performed supervision and funding acquisition. JAGF and CKF reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Not applicable.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- GBD 2019 Adolescent Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national mortality among young people aged 10-24 years, 1950-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2021;398(10311), 1593–1618.

Crossref - Schwartz B, Klamer K, Zimmerman J, Kale-Pradhan PB, Bhargava A. Multidrug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Clinical Settings: A Review of Resistance Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies. Pathogens. 2024;13(11):975.

Crossref - Frem JA, Doumat G, Kazma J, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality in patients with pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. PLOS ONE. 2023;18(4):e0282276.

Crossref - Qin S, Xiao W, Zhou C, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances and emerging therapeutics. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):199.

Crossref - Wu M, Yang X, Tian J, Fan H, Zhang Y. Antibiotic Treatment of Pulmonary Infections: An Umbrella Review and Evidence Map. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:680178.

Crossref - Ibrahim D, Jabbour JF, Kanj SS. Current choices of antibiotic treatment for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2020;33(6):464-473.

Crossref - Chi AA, Rus LL, Morgovan C, et al. Microbial Resistance to Antibiotics and Effective Antibiotherapy. Biomedicines. 2022;10(5):1121.

Crossref - Pang Z, Raudonis R, Glick BR, Lin T-J, Cheng Z. Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Mechanisms and Alternative Therapeutic Strategies. Biotechnol Adv. 2019;37(1):177–192.

Crossref - Thi MTT, Wibowo D, Rehm BHA. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(22):8671.

Crossref - Sharma S, Mohler J, Mahajan SD, Schwartz SA, Bruggemann L, Aalinkeel R. Microbial Biofilm: A Review on Formation, Infection, Antibiotic Resistance, Control Measures, and Innovative Treatment. Microorganisms. 2023;11(6):1614.

Crossref - Almattoudi A. Biofilm Resilience: Molecular Mechanisms Driving Antibiotic Resistance in Clinical Contexts. Biology. 2025;14(2):165.

Crossref - Tuon FF, Dantas LR, Suss PH, Tasca Ribeiro VS. Pathogenesis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm: A Review. Pathogens. 2022;11(3):300.

Crossref - Oliveira M, Cunha E, Tavares L, Serrano I. P. aeruginosa interactions with other microbes in biofilms during co-infection. AIMS Microbiol. 2023;9(4):612-646.

Crossref - Mirghani R, Saba T, Khaliq H, et al. Biofilms: Formation, drug resistance and alternatives to conventional approaches. AIMS Microbiol. 2022;8(3):239–277.

Crossref - Shree P, Singh CK, Sodhi KK, Surya JN, Singh DK. Biofilms: Understanding the structure and contribution towards bacterial resistance in antibiotics. Med Microecol. 2023;16:100084.

Crossref - Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze Z, Morris Jr. JG. Bacteriophage Therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(3):649-659.

Crossref - Gill JJ, Hyman P. Phage Choice, Isolation, and Preparation for Phage Therapy. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2010;11(1):2-14.

Crossref - Haq IU, Rahim K, Paker NP. Exploring the historical roots, advantages and efficacy of phage therapy in plant diseases management. Plant Sci. 2024;346:112164.

Crossref - Olawade DB, Fapohunda O, Egbon E, et al. Phage Therapy: A Targeted Approach to Overcoming Antibiotic Resistance. Microb Pathog. 2024;19:107088.

Crossref - Lin DM, Koskella B, Lin HC. Phage therapy: an Alternative to Antibiotics in the Age of multi-drug Resistance. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8(3):162-173.

Crossref - Levin BR, Rozen DE. Non-inherited antibiotic resistance. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2006;4(7):556–562.

Crossref - Zhang M, Zhang T, Yu M, Chen Y-L, Jin M. The Life Cycle Transitions of Temperate Phages: Regulating Factors and Potential Ecological Implications. Viruses. 2022;14(9):1904.

Crossref - Kraemer JA, Erb ML, Waddling CA, et al. A Phage Tubulin Assembles Dynamic Filaments by an Atypical Mechanism to Center Viral DNA within the Host Cell. Cell. 2012;149(7):1488-1499.

Crossref - Kizziah JL, Mukherjee A, Parker LK, Dokland T. Structure of the Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophage 80ב neck shows the interactions between DNA, tail completion protein and tape measure protein. Structure. 2025;33(6):1063-1073.

Crossref - Xia G, Wolz C. Phages of Staphylococcus aureus and their impact on host evolution. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;21:593-601.

Crossref - Wilson MG, Pandey S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) 2023.

- de Sousa T, Hebraud M, Dapkevicius MLNE, et al. Genomic and Metabolic Characteristics of the Pathogenicity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(23):12892.

Crossref - Peterson JW. Bacterial Pathogenesis. In: Baron S. (4th eds). Medical Microbiology. Univ of Texas Medical Branch. 1996

- Zulianello L, Canard C, Kohler T, Caille D, Lacroix J-S, Meda P. Rhamnolipids Are Virulence Factors That Promote Early Infiltration of Primary Human Airway Epithelia by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 2006;74(6):3134–3147.

Crossref - Rossy T, Distler T, Meirelles LA, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type IV pili actively induce mucus contraction to form biofilms in tissue-engineered human airways. PLOS Biol. 2023;21(8):e3002209-e3002209.

Crossref - Sahu A, Ruhal R. Immune system dynamics in response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 2025;11(1):104.

Crossref - Jurado-Martin I, Sainz-Mejias M, McClean S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An Audacious Pathogen with an Adaptable Arsenal of Virulence Factors. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):3128.

Crossref - Malhotra S, Hayes D, Wozniak DJ. Cystic Fibrosis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: The Host-Microbe Interface. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32(3):e00138-18.

Crossref - Jackson L, Waters V. Factors influencing the acquisition and eradication of early Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibross. 2021;20(1):8-16.

Crossref - CDC. 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report. Antimicrobial Resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/data-research/threats/index.html

- Ettu AO, Oladapo BA, Oduyebo OO. Prevalence of carbapenemase production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates causing clinical infections in Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology, 22(4): 498-503.

Crossref - Da Silva Ribeiro ÁC, Crozatti MTL, Da Silva AA, Macedo RS, De Oliveira Machado AM, De Albuquerque Silva AT. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the ICU: Prevalence, resistance profile, and antimicrobial consumption. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2019;53:e20180498.

Crossref - Chai Y-H, Xu J-F. How does Pseudomonas aeruginosa affect the progression of bronchiectasis? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(3):313–318.

Crossref - Cosgrove SE. The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2006;42(Suppl 2):S82-89.

Crossref - de Kraker MEA, Davey PG, Grundmann H. Mortality and hospital stay associated with resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli bacteremia: estimating the burden of antibiotic resistance in Europe. PLoS Med. 2011;8(10):e1001104.

Crossref - Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;18(3):268-281.

- CDC (United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019;2019 AR Threats Report; Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019:1-118.

Crossref - Zalewska-Piatek B. Phage Therapy—Challenges, Opportunities and Future Prospects. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16(12):1638.

Crossref - O’Neill J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance; HM Government and Welcome Trust: London, UK. 2016:1-76. https://apo.org.au/node/63983 (accessed on 12 January 2019).

- Carlton RM. Phage therapy: past history and future prospects. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 1999;47(5):267-274.

- Catherine Loc-Carrillo, Loc-Carrillo C, Stephen T. Abedon, Abedon ST. Pros and cons of phage therapy. Bacteriophage. 2011;1(2):111-114.

Crossref - Uddin TM, Chakraborty AJ, Khusro A, et al. Antibiotic Resistance in microbes: History, mechanisms, Therapeutic Strategies and Future Prospects. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 2021;14(12):1750–1766. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034121003403

- Riedel S, Morse SA, Mietzner TA, Miller S (eds). Ryan KJ, Ray CG. Jawetz, Melnick, & Adelberg’s Medical Microbiology (28th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. 2021.

- Roberts MC. Update on acquired tetracycline resistance genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;245(2):195-203.

Crossref - Levy SB, Marshall B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat Med. 2004;10(12 Suppl):S122-129.

Crossref - Tenover FC. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. American Journal of Infection Control, 2006;34(5): S3–S10.

Crossref - Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284(5418):1318-1322.

Crossref - Hoiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Moser C, et al. ESCMID* guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of biofilm infections 2014. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:S1-25.

Crossref - Larsson DGJ, de Pedro C, Paxeus N. Effluent from drug manufactures contains extremely high levels of pharmaceuticals. J Hazard Mater. 2007;148(3):751-755.

Crossref - Rahman MS, Hassan MM, Chowdhury S. Determination of antibiotic residues in milk and assessment of human health risk in Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2021;7(8):e07739.

Crossref - Vila MMDC, Balcão LMN, Balcão VM. Phage Delivery Strategies for Biocontrolling Human, Animal, and Plant Bacterial Infections: State of the Art. Pharmaceutics, 2024;16(3):374-374.

Crossref - Duzgunes N, Sessevmez M, Yildirim M. Bacteriophage Therapy of Bacterial Infections: The Rediscovered Frontier. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(1):34.

Crossref - Vila MMDC Liliane MNB. Balcao VM. Phage Delivery Strategies for Biocontrolling Human, Animal, and Plant Bacterial Infections: State of the Art. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(3):374-374.

Crossref - Abedon ST. Phage therapy of pulmonary infections. Bacteriophage.2015;5(1):e1020260.

Crossref - Biswas B, Adhya S, Washart P, et al. Bacteriophage Therapy Rescues Mice Bacteremic from a Clinical Isolate of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium. Infect Immun. 2002;70(1):204-210.

Crossref - Mitropoulou G, Koutsokera A, Csajka C, et al. Phage therapy for pulmonary infections: lessons from clinical experiences and key considerations. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31(166):220121.

Crossref - Lusiak-Szelachowska M, Zaczek M, Weber-Dabrowska B, et al. Phage Neutralization by Sera of Patients Receiving Phage Therapy. Viral Immunol. 2014;27(6):295–304.

Crossref - Mei L, Zhang Z, Zhao L, et al. Pharmaceutical nanotechnology for oral delivery of anticancer drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(6):880-890.

Crossref - Schubert C, Fischer S, Dorsch K, Teßmer L, Hinrichs J, Atamer Z. Microencapsulation of bacteriophages for the delivery to and modulation of the human gut microbiota through milk and cereal products. Appl Sci. 2022;12(13):6299. doi: 10.3390/app12136299. Correction published 2023;13(9):5305.

Crossref - Rahimzadeh G, Saeedi M, Moosazadeh M, et al. Encapsulation of bacteriophage cocktail into chitosan for the treatment of bacterial diarrhea. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):15603.

Crossref - Dabrowska K, Abedon ST. Pharmacologically Aware Phage Therapy: Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Obstacles to Phage Antibacterial Action in Animal and Human Bodies. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2019;83(4):e00012-19.

Crossref - Chang RYK, Chow MYT, Wang Y, et al. The effects of different doses of inhaled bacteriophage therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa pulmonary infections in mice. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28(7):983-989.

Crossref - Sahota JS, Smith CM, Radhakrishnan P, et al. Bacteriophage Delivery by Nebulization and Efficacy Against Phenotypically Diverse Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Cystic Fibrosis Patients. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2015;28(5):353-360.

Crossref - Carrigy NB, Chang RY, Leung SSY, et al. Anti-Tuberculosis Bacteriophage D29 Delivery with a Vibrating Mesh Nebulizer, Jet Nebulizer, and Soft Mist Inhaler. Pharm Res. 2017;34(10):2084-2096.

Crossref - Leung SSY, Carrigy NB, Vehring R, et al. Jet nebulization of bacteriophages with different tail morphologies – Structural effects. Int J Pharm. 2019;554:322-326.

Crossref - Loh B, Gondil VS, Manohar P, Khan FM, Yang H, Leptihn S. Encapsulation and Delivery of Therapeutic Phages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2021;87(5):e01979.

Crossref - Musin EV, Kim AL, Dubrovskii AV, Kudryashova EB, Ariskina EV, Tikhonenko SA. The Influence of Polyanions and Polycations on Bacteriophage Activity. Polymers. 2021;13(6):914.

Crossref - Ganeshan SD, Hosseinidoust Z. Phage Therapy with a focus on the Human Microbiota. Antibiotics. 2019;8(3):131.

Crossref - Nieth A, Verseux C, Barnert S, Suss R, Romer W. A first step toward liposome-mediated intracellular bacteriophage therapy. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12(9):1411–1424.

Crossref - Cafora M, Poerio N, Forti F, et al. Evaluation of phages and liposomes as combination therapy to counteract Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in wild-type and CFTR-null models. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:979610.

Crossref - Chegini Z, Khoshbayan A, Moghadam MT, Farahani I, Jazireian P, Shariati A. Bacteriophage therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: A review. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020;19(1):45.

Crossref - Nawaz A, Khalid NA, Zafar S, et al. Phage therapy as a revolutionary treatment for multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: A narrative review. The Microbe. 2024;2:100030.

Crossref - Jo SJ, Kwon J, Kim SG, Lee S-J. The Biotechnological Application of Bacteriophages: What to Do and Where to Go in the Middle of the Post-Antibiotic Era. Microorganisms. 2023;11(9):2311.

Crossref - Alharbi NM, Ziadi MM. Wastewater As A Fertility Source For Novel Bacteriophages Against Multi-Drug Resistant Bacteria. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(8):4358-4364.

Crossref - Palma M, Qi B. Advancing Phage Therapy: A Comprehensive Review of the Safety, Efficacy, and Future Prospects for the Targeted Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Infect Dis Rep. 2024;16(6):1127-1181.

Crossref - Fong SA, Drilling A, Morales S, et al. Activity of Bacteriophages in Removing Biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates from Chronic Rhinosinusitis Patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:418.

Crossref - Kim S, Rahman M, Seol SY, Yoon SS, Kim J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bacteriophage PA1Ø Requires Type IV Pili for Infection and Shows Broad Bactericidal and Biofilm Removal Activities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(17):6380-6385.

Crossref - Szermer-Olearnik B, Filik-Matyjaszczyk K, Ciekot J, Czarny A. The Hydrophobic Stabilization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bacteriophage F8 and the Influence of Modified Bacteriophage Preparation on Biofilm Degradation. Curr Microbiol. 2024;81(11).

Crossref - Aqeel M, Bukhari SMAUS, Ullah H, et al. Evaluation of the Bacteriophage MAC-1 Potential to Control Pseudomonas aeruginosa Planktonic Cells and Biofilms. Sains Malaysiana. 2024;53(5):1043-1054.

Crossref - Kunisch F, Campobasso C, Wagemans J, et al. Targeting Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm with an evolutionary trained bacteriophage cocktail exploiting phage resistance trade-offs. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):8572.

Crossref - Yang X, Hussain W, Chen Y, et al. A New type of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Phage with Potential as a Natural Food Additive for Eradicating biofilms and Combating Multidrug-Resistant Strains. Food Control. 2024;168:110888.

Crossref - Manohar P, Loh B, Nachimuthu R, Leptihn S. Phage-antibiotic combinations to control Pseudomonas aeruginosa–Candida two-species biofilms. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):9354.

Crossref - Santamaria-Corral G, Aguilera-Correa JJ, Esteban J, Garcia-Quintanilla M. Bacteriophage Therapy on an In Vitro Wound Model and Synergistic Effects in Combination with Beta-Lactam Antibiotics. Antibiotics. 2024;13(9):800–800.

Crossref - Abdelghafar A, El-Ganiny A, Shaker G, Askoura M. A novel lytic phage exhibiting a remarkable in vivo therapeutic potential and higher antibiofilm activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023;42(10):1207-1234.

Crossref - Manohar P, Loh B, Turner D, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the biofilm-degrading Pseudomonas phage Motto, as a candidate for phage therapy. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1344962.

Crossref - Suresh S, Saldanha J, Shetty BA, Premanath R, Akhila DS, Raj JRM. Comparison of Antibiofilm Activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Phages on Isolates from Wounds of Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients. Microorganisms. 2023;11(9):2230.

Crossref - Gordon M, Ramirez P. Efficacy and Experience of Bacteriophages in Biofilm-Related Infections. Antibiotics. 2024;13(2):125-125.

Crossref - Wang Z, Soir SD, Glorieux A, et al. Bacteriophages as potential antibiotic potentiators in cystic fibrosis: A new model to study the combination of antibiotics with a bacteriophage cocktail targeting dual species biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2024;64(3):107276-107276.

Crossref - Meneses L, Sillankorva S, Azeredo J. Bacteriophage Control of Infectious Biofilms. In: Azeredo J, Sillankorva S. (eds) Bacteriophage Therapy. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol 2734. Humana, New York, NY. 2023;141-150.

Crossref - Alipour-Khezri E, Moqadami A, Barzegar A, Mahdavi M, Skurnik M, Zarrini G. Bacteriophages and Green Synthesized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Combination Are Efficient against Biofilm Formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Viruses. 2024;16(6):897.

Crossref - Shi Z, Hong X, Li Z, et al. Characterization of the novel broad-spectrum lytic phage Phage_Pae01 and its antibiofilm efficacy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol. 2024;15.

Crossref - Martinho I, Braz M, Duarte J, et al. The Potential of Phage Treatment to Inactivate Planktonic and Biofilm-Forming Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microorganisms. 2024;12(9):1795.

Crossref - Tagliaferri TL, Jansen M, Horz H-P. Fighting Pathogenic Bacteria on Two Fronts: Phages and Antibiotics as Combined Strategy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:22.

Crossref - Santamaria-Corral G, Senhaji-Kacha A, Broncano-Lavado A, Esteban J, Garcia-Quintanilla M. Bacteriophage–Antibiotic Combination Therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics. 2023;12(7):1089.

Crossref - Lin Y, Chang RYK, Britton WJ, Morales S, Kutter E, Chan H-K. Synergy of nebulized phage PEV20 and ciprofloxacin combination against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Pharm. 2018;551(1-2):158–165.

Crossref - Chang RYK, Chen K, Wang J, et al. Proof-of-Principle Study in a Murine Lung Infection Model of Antipseudomonal Activity of Phage PEV20 in a Dry-Powder Formulation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;62(2):e01714-17.

Crossref - Kohler T, Luscher A, Falconnet L, et al. Personalized aerosolised bacteriophage treatment of a chronic lung infection due to multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):3629-3629.

Crossref - Hu X, Duan L, Jiang G, Wang H, Liu H, Chen C. A clinical risk model for the evaluation of bronchopleural fistula in non-small cell lung cancer after pneumonectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(2):419–424.

Crossref - Jichen QV, Chen G, Jiang G, Ding J, Gao W, Chen C. Risk factor comparison and clinical analysis of early and late bronchopleural fistula after non-small cell lung cancer surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(5):1589-1593.

Crossref - Hitchcock NM, Nunes DDG, Shiach J, et al. Current Clinical Landscape and Global Potential of Bacteriophage Therapy. Viruses. 2023;15(4):1020.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.