ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

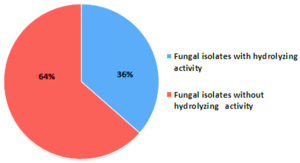

This study was conducted with the aim of isolating filamentous fungi capable of producing important industrial enzymes like protease, amylase and cellulase from different forest soils of Arunachal Pradesh, North Eastern India. Cellulase and amylase production by filamentous fungi were screened on Mandel and Reese agar (MRA) supplemented with CMC-Na cellulose and starch agar (SA) media. Screening of protease production was carried out on skimmed milk agar (SMA) plates. A total of 85 fungal isolates were screened for three enzyme activities. Thirty one fungal isolates (36%) were found to produce the three extracellular enzymes. Twenty five (25) fungal isolates have shown protease production followed by 12 isolates for amylase and 10 isolates displaying cellulase production. Aspergillus flavus produced highest protease hydrolyzing index (2.74 ± 0.21) while Penicillium chrysogenum and Purpureocillium sp. showed highest hydrolyzing indices for amylase (2.58 ± 0.11) and cellulase enzyme (1.51 ± 0.09) respectively. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed statistically significant variation in size of hydrolyzing zones of the three enzymes among the fungal isolates. Four species of filamentous fungi, A. flavus, Penicillium jensenii, P. chrysogenum and P. spinulosum were found to show all three enzyme activities. Further studies on optimization of culture media of these filamentous fungi could lead to large scale production of the three important enzymes for commercial applications.

Aspergillus flavus, Enzymes, Fungi, Penicillium chrysogenum, Soil

Enzymes are biomolecules, mostly proteins produced by living organisms and play key roles as catalysts in various biochemical and metabolic reactions of all the life supporting processes inside the cells. Enzymes actively influence all the life supporting processes such as biosynthesis of metabolites, DNA replication, production of cellular energy, protein synthesis, signal transduction, tissue regeneration, etc.1 Enzymes influence the rate of reactions by decreasing energy requirement and possess high substrate specificity for most of the biochemical reactions they catalyze. The enzymes have earned a secure place in the ever-growing industrial markets for production of drugs, medicine, cosmetics, food products, detergents, de-stainer for dyes and paints, etc. The value of industrially important enzymes is estimated at about € 6.95 billion in the year 2022 globally and it is expected to grow at CAGR of 6.4% from 2023 to 2050.2

Industrially important enzymes such as amylase, cellulase and protease are widely used in different preparation of detergent, food, feed, paper and pulp and pharmaceuticals.3 Cellulose is the most abundant polysaccharide in nature which is a polymer of glucose with β-glycosidic linear chains. Complex cellulose is broken down by cellulases to common saccharides or energy rich ethanol which play keys role in making of industrial products like food, medicine, paper, fabric, fruit drinks and biofuel production.4 Starch is also a complex polymer of glucose which differs from cellulose in presence of α-glycosidic bonds and branched chain structures. They are also abundant in nature and can be used as a resource for regeneration of bioenergy. Amylase enzymes break down starch molecules and these enzymes are also used in industries like paper-pulp, production of food and beverages.5 Protease cleaves the peptide bonds in proteins. They occupy 60% of the enzyme market share in the world due to their vast range of applications in various industries such as food, pharmaceuticals, detergent and leather tanning.6,7

The natural sources of enzymes are living organisms. Though plants and animals serve as source of important enzymes namely bromelain, papain, ficin, pepsin and rennin, most of the industrially used enzymes such as cellulase and chitinase are derived from microorganisms, particularly bacteria and fungi.8 Microbial enzymes are considered to be advantageous over enzymes from plants due to several reasons such as lower cost of production, less space requirement, less time required for production, continuous availability of source organisms and higher production capacity. Fungi, bacteria and actinomycetes are mainly used for production of commercial enzymes.9 However, one of advantages of fungi as source of industrial enzyme is that they can produce large quantities of extracellular enzymes, particularly cellulase. For example, Trichoderma species is used for production of industrial cellulases as compared to bacterial strains since the retrieval of the enzyme is much easier from fungi than in bacteria.10 The number of described species of fungi is about 150,000 which represent only 10% of the estimated total of 1.5 million fungi present in the biosphere.11 Despite enormous diversity of fungal species, only very few species namely Aspergillus niger, Trichoderma reesei and Penicillium chrysogenum have been used for commercial production of enzymes.12 It is assumed that there must be a large number of unexplored fungal species which could serve as potential sources of industrially important enzymes. Therefore, the present study aimed to explore, isolate and screen filamentous fungi for potential production of amylase, cellulase and protease enzymes from the soils of different forest ecosystems in Arunachal Pradesh, India.

Collection of soil samples

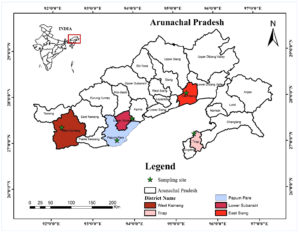

Soil samples were collected from five study sites, (i) Bamboo forests of Papum Pare District, (ii) Tropical Semi-Evergreen Forests of East Siang District, (iii) Alpine Forests of West Kameng, (iv) Moist Evergreen forests of Deomali District and (v) Temperate Broad-Leaved and Coniferous Forests of Talley Wildlife Sanctuary in Arunachal Pradesh, North Eastern India (Figure 1). A total of 27 soil samples (9 sub-samples from 3 sub-plots) were collected from surface soil of each of the study sites. The samples were properly labelled and transported to the laboratory for processing and further analysis. The replicate samples (27 sub-samples) were mixed to get homogenous mixture for each site. The soil samples were passed through a test sieve (2 mm) to remove coarse roots, organic debris, pebbles, etc. Three replicates of the fresh homogeneous soil mixture were used for isolation of fungi immediately after soil processing. The processed soil samples were stored in 4 °C until further use.

Figure 1. Map of Arunachal Pradesh (India) showing soil sampling sites for isolation of filamentous soil fungi

Isolation of filamentous fungi

Isolation of filamentous fungi from the soil samples were carried out using serial dilution plate technique. A sample of fresh soil (10 g) was suspended in 90 ml of sterile distilled water and a soil suspension stock (10-1) was prepared by shaking at 100 rpm for 6 to 12 hours at room temperature. Serial dilutions of 10-2 to 10-3 were prepared by transferring 1 ml of the soil suspension stock into a test tube containing 9 ml of sterile water by mixing thoroughly using a vortex mixer to get a dilution of 10-2. Then, 1 ml of the dilution (10-2) was transferred into another tube containing 9 ml of sterile water followed by a thorough mixing to get 10-3 dilution. Four different culture media, Potato dextrose agar (PDA, potato powder – 4 g, dextrose – 20 g, agar – 15 g, distilled water – 1000 ml, pH – 5.6 ± 0.2), Czapek’s dox agar (CDA, Sucrose – 30 g, NaNO3 – 2 g, K2HPO4 – 1 g, MgSO4 – 0.5 g, KCl – 0.5 g, FeSO4 – 0.01 g, agar – 20 g, distilled water -1000 ml, pH – 7.3 ± 0.2), Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA, glucose – 20 g, peptone – 10 g, agar – 20 g, distilled water – 1000 ml, pH – 5.6 ± 0.2) and Rose-Bengal agar (RBA, peptone – 5.0 g, dextrose – 10 g, KH2PO4 – 1.0 g, MgSO4.7H2O – 0.5 g, Rose-Bengal – 0.035 g, streptomycin – 0.03 g, agar – 15 g, make up the volume 1000 ml with distilled water, pH – 7.2 ± 0.2) were prepared by autoclaving for 15 minutes at 121 °C and 15 psi. A volume of 100 µl inoculum from 10-3 dilution was evenly spread out on media plates with the help of sterile L-spreader. The plates were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 3-7 days. The fungal colonies were sub-cultured in PDA to get pure cultures. Pure isolates were maintained in PDA slants and stored at 4 °C for further studies. The experiment was carried out in triplicates. Pure cultures of fungal isolates (Culture IDs labelled with NFML3374 to NFML3458) were stored and maintained at the Laboratory of Microbiology and Biotechnology, Department of Forestry, North Eastern Regional Institute of Science and Technology, Nirjuli, Arunachal Pradesh, India.

Screening of cellulase, amylase and protease enzyme production by filamentous fungi

Production of cellulase enzyme by filamentous fungi was carried out by inoculating the pure culture isolates of fungi on Mandel and Reese Agar plates (MRA, KH2PO4 – 2 g,

(NH4)2SO4 – 1.4 g, MgSO4.7H2O-0.3 g, CaCl2-0.3 g, Yeast extract – 0.4 g, FeSO4.7H2O – 0.005 g, MnSO4 – 0.0016 g, ZnCl2 – 0.0017 g, CoCl2 – 0.002 g, Agar -15.0 g, distilled water – 1000 ml and pH – 5.0 supplemented with 0.5% CMC-Na cellulose).13 The plates were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 3-7 days. After incubation, the plates were stained with 1% congo red solution for 15 minutes followed by destaining with 1M NaCl solution for 15 minutes. The presence of clear halo zones around the fungal colonies which indicates cellulose hydrolysis by cellulase enzyme released from the fungi were recorded.13 Screening of amylase production by the fungal isolates were carried by inoculating the fungal isolates on Starch Agar (SA) medium (Hi-Media, M107S) at 28 ± 2 °C for 3-10 days. After incubation, the plates were flooded with iodine solution to observe clear hydrolyzing zones around the fungal colonies as indicator of starch hydrolysis by amylase.14 The production of protease by fungal isolates were screened on skimmed milk agar medium (SMA, skimmed milk powder – 28 g, tryptone – 5 g, yeast extract – 3 g, dextrose – 1 g, agar – 15 g, distilled water – 1000 ml ph – 7.0 ± 0.2).15 The fungal isolates were inoculated on the SMA plates and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 3-10 days. Formation of clear zones around the fungal colonies due to casein hydrolysis as indicator of extracellular protease activity were observed and recorded.

Determination of hydrolyzing indices

The hydrolyzing indices of fungal isolates on different media were determined by measuring the area of hydrolyzing zones around the fungal colonies. The diameter of fungal colonies and hydrolyzing zones were measured and the hydrolyzing indices were calculated as follows.16,17

Hydrolyzing index = Colony Diameter + Diameter of Halo Zone / Colony diameter

Identification of the fungal isolates

The fungal isolates showing presence of significant hydrolyzing zones and indices were identified based on their morphological and microscopic characters.18,19

Statistical analysis of enzyme hydrolyzing zones

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was calculated for production of hydrolyzing zones of all the three enzymes (amylase, cellulase and protease) by different species of fungi in Origin 7 statistical software. The results are expressed as means and standard deviation (SD) of three replicate analyses.

Isolation and identification of filamentous fungi

A total of 85 filamentous fungi were isolated from five different sites (Table 1). Thirteen (13) fungi were isolated from bamboo forests of Papum Pare district, 14 fungi from Tropical Semi-Evergreen forests of East Siang district, 19 fungi from Alpine forests of West Kameng district, 18 fungi from Moist Evergreen forests of Deomali district and 21 fungi were isolated from temperate broad-Leaved and Coniferous forests of Talley Wildlife Sanctuary. Colony morphology and microscopic characters of fungal isolates showing enzyme production are provided in supplementary information (Table S1 and Figure S1).

Table (1):

Number of fungi isolated from different study sites on different fungal culture media

| No. | Sites of sample collection | Media* | No. of isolates | Total no. of isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bamboo forests of Papum Pare district | PDA | 5 | 13 |

| CZA | 3 | |||

| SDA | 3 | |||

| RBA | 2 | |||

| 2. | Tropical Semi-Evergreen forests of East Siang district | PDA | 5 | 14 |

| CZA | 4 | |||

| SDA | 3 | |||

| RBA | 2 | |||

| 3. | Alpine forests of West Kameng district | PDA | 7 | 19 |

| CZA | 5 | |||

| SDA | 4 | |||

| RBA | 3 | |||

| 4. | Moist evergreen forests of Deomali district | 7 | 18 | |

| 4 | ||||

| 4 | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| 5. | Temperate broad leaved and coniferous forests of Tale Wildlife Sanctuary | PDA | 9 | 21 |

| CZA | 4 | |||

| SDA | 5 | |||

| RBA | 3 | |||

| Total number of fungal isolates | 85 | |||

*(PDA = Potato Dextrose Agar; CZA = Czapek’s Dox Agar; Sabouraud Dextrose Agar; RBA = Rose-Bengal Agar)

Hydrolyzing properties of cellulase, amylase and protease enzymes

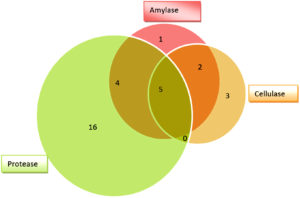

All the 85 fungal isolates were screened for production of cellulase, amylase and protease enzymes based on presence of hydrolyzing zones (halo/clear zones) surrounding the fungal colonies on culture media. Thirty one (31) fungal isolates (36%) were found to show hydrolyzing zones on three different culture media (SA, SMA and MRA) as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. Many fungal isolates have shown presence of more than one enzyme as shown by production of hydrolyzing zones on different media i.e. multiple enzyme production by same fungus. Twenty five (25) fungal isolates have shown protease hydrolyzing zones followed by 12 isolates with amylase hydrolyzing zones and 10 isolates displaying cellulase hydrolyzing zones (Figure 3). Nine (9) isolates have shown both amylase and protease hydrolyzing zones, 7 isolates were found to show amylase and cellulase hydrolyzing zones, 5 isolates have shown cellulase and protease hydrolyzing zones and 5 isolates have shown hydrolyzing zones of all the three enzymes.

Table (2):

Fungal isolates showing hydrolyzing zones for cellulase, amylase and protease enzymes

| No. | Isolate ID | Isolate No. | Enzyme Production* | No. | Culture ID | Isolate No. | Enzyme Production | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | AA | PA | CA | AA | PA | ||||||

| 1 | NFML3374 | T5 | + | + | – | 44 | NFML3417 | T262 | – | – | – |

| 2 | NFML3375 | T11 | – | – | – | 45 | NFML3418 | T263 | – | – | – |

| 3 | NFML3376 | T15 | – | – | – | 46 | NFML3419 | T264 | – | – | – |

| 4 | NFML3377 | T32 | – | – | – | 47 | NFML3420 | T265 | – | – | + |

| 5 | NFML3378 | T66 | – | – | – | 48 | NFML3421 | T266 | – | – | – |

| 6 | NFML3379 | T68 | + | + | – | 49 | NFML3422 | T267 | – | – | + |

| 7 | NFML3380 | T71 | – | – | – | 50 | NFML3423 | T269 | – | – | – |

| 8 | NFML3381 | T72 | + | + | + | 51 | NFML3424 | T271 | – | + | + |

| 9 | NFML3382 | T78 | – | – | – | 52 | NFML3425 | T273 | – | – | – |

| 10 | NFML3383 | T82 | – | – | – | 53 | NFML3426 | T274 | – | – | + |

| 11 | NFML3384 | T107 | – | + | – | 54 | NFML3427 | T275 | – | – | + |

| 12 | NFML3385 | T110 | – | – | – | 55 | NFML3428 | T276 | – | – | + |

| 13 | NFML3386 | T112 | + | + | + | 56 | NFML3429 | T277 | – | – | – |

| 14 | NFML3387 | T124 | – | – | – | 57 | NFML3430 | T278 | – | – | – |

| 15 | NFML3388 | T134 | + | + | + | 58 | NFML3431 | T279 | – | + | + |

| 16 | NFML3389 | T137 | – | – | – | 59 | NFML3432 | T281 | – | – | – |

| 17 | NFML3390 | T140 | – | – | – | 60 | NFML3433 | T283 | + | – | – |

| 18 | NFML3391 | T160 | – | – | – | 61 | NFML3434 | T284 | – | – | + |

| 19 | NFML3392 | T161 | – | – | – | 62 | NFML3435 | T285 | + | – | + |

| 20 | NFML3393 | T182 | + | + | + | 63 | NFML3436 | T286 | – | – | – |

| 21 | NFML3394 | T184 | – | – | – | 64 | NFML3437 | T287 | – | – | – |

| 22 | NFML3395 | T190 | – | – | – | 65 | NFML3438 | T292 | – | – | – |

| 23 | NFML3396 | T192 | – | – | – | 66 | NFML3439 | T293 | – | – | – |

| 24 | NFML3397 | T200 | – | – | – | 67 | NFML3440 | T294 | – | – | – |

| 25 | NFML3398 | T208 | – | – | – | 68 | NFML3441 | T296 | – | – | + |

| 26 | NFML3399 | T209 | – | – | – | 69 | NFML3442 | T297 | – | – | – |

| 27 | NFML3400 | T212 | – | – | – | 70 | NFML3443 | T298 | – | – | + |

| 28 | NFML3401 | T217 | – | + | + | 71 | NFML3444 | T300 | – | – | – |

| 29 | NFML3402 | T234 | – | + | + | 72 | NFML3445 | T303 | – | – | – |

| 30 | NFML3403 | T235 | – | – | + | 73 | NFML3446 | T306 | – | – | – |

| 31 | NFML3404 | T236 | – | – | + | 74 | NFML3447 | T313 | – | – | – |

| 32 | NFML3405 | T240 | – | – | – | 75 | NFML3448 | T315 | + | – | – |

| 33 | NFML3406 | T243 | – | – | + | 76 | NFML3449 | T321 | – | – | – |

| 34 | NFML3407 | T244 | – | – | + | 77 | NFML3450 | T334 | – | – | – |

| 35 | NFML3408 | T245 | – | – | – | 78 | NFML3451 | T338 | + | + | + |

| 36 | NFML3409 | T247 | – | – | + | 79 | NFML3452 | T341 | – | – | – |

| 37 | NFML3410 | T248 | – | – | + | 80 | NFML3453 | T346 | – | – | – |

| 38 | NFML3411 | T250 | – | – | – | 81 | NFML3454 | T349 | – | – | – |

| 39 | NFML3412 | T254 | – | – | – | 82 | NFML3455 | T371 | – | – | – |

| 40 | NFML3413 | T258 | – | – | – | 83 | NFML3456 | T377 | – | – | – |

| 41 | NFML3414 | T259 | – | – | – | 84 | NFML3457 | T379 | + | – | – |

| 42 | NFML3415 | T260 | – | – | + | 85 | NFML3458 | T415 | – | – | – |

| 43 | NFML3416 | T261 | – | – | – | ||||||

(Presence or absence hydrolyzing zones are indicated by ‘+’ and ‘-’ signs)

*CA = Cellulase, AA = Amylase, PA = Protease

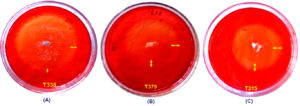

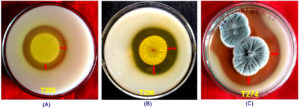

Hydrolyzing activity and index of cellulase enzyme on MRA plates

The hydrolyzing index of cellulase enzyme as indicator of production of cellulase were determined by observing formation of halo (clear) zones around the fungal colonies on MRA plates. The halo zones produced due to hydrolysis of CMC-Na cellulose to glucose after release of cellulase enzyme by the filamentous fungus became visible when the media was flooded with Congo Red dye (Figure 4). The diameter of the halo zones on the MRA plates varied from a minimum of 0.18 ± 0.06 cm and hydrolyzing index of 1.06 ± 0.02 by isolate number NFML3381 to a maximum of 0.87 ± 0.12 cm and hydrolyzing index of 1.51 ± 0.09 by NFML3448 (Table 3). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) among the fungal isolates revealed significantly different cellulase hydrolyzing zones (F = 48.88; p ≤ 0.001). Six of the fungal isolates producing cellulase enzyme were identified as Penicillium, 2 isolates were Aspergillus, 1 isolate was Purpureocillium and 1 isolate was designated as sterile hyphae. The fungal isolate, Purpureocillium sp. (NFML3448) displayed highest cellulase hydrolyzing zone.

Table (3):

Fungal isolates with cellulose hydrolyzing properties

Isolate ID. |

Fungal species |

Hydrolyzing zone (cm ± SD) |

Hydrolyzing Index (±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

NFML3381 |

Aspergillus flavus |

0.18 ± 0.06 |

1.06 ± 0.02 |

NFML3433 |

Penicillium decumbens |

0.20 ± 0.05 |

1.07 ± 0.02 |

NFML3393 |

Penicillium simplicissimum |

0.23 ± 0.08 |

1.08 ± 0.03 |

NFML3374 |

Penicillium chrysogenum |

0.30 ± 0.09 |

1.11 ± 0.04 |

NFML3386 |

Penicillium citrinum |

0.30 ± 0.18 |

1.11 ± 0.08 |

NFML3379 |

Sterile hyphae |

0.42 ± 0.08 |

1.14 ± 0.03 |

NFML3451 |

Penicillium spinulosum |

0.50 ± 0.05 |

1.20 ± 0.02 |

NFML3388 |

Penicillium chrysogenum |

0.52 ± 0.03 |

1.21 ± 0.01 |

NFML3457 |

Aspergillus sp. |

0.82 ±0.06 |

1.45 ± 0.03 |

NFML3448 |

Purpureocillium sp. |

0.87 ± 0.12 |

1.51 ± 0.09 |

Values are means of triplicate analyses with standard deviation (±SD)

Figure 4. Fungal isolate T338 (NFML3451), T379 (NFML3457) and T315 (NFML3448) showing cellulase hydrolyzing activities on MRA plates (A-C) Yellow arrows indicate halo/clear zones on MRA plates due to cellulase activity

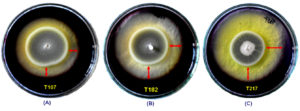

Hydrolyzing activity and index of amylase enzyme on SA plates

Production of clear zone around the fungal colonies as a result of digestion of starch by the amylase enzyme were screened on the SA plates. The formation of clear zone was observed after flooding with iodine solution in the SA plates (Figure 5). The hydrolyzing zones and indices of amylase enzyme of different fungal isolates are shown in Table 4. The hydrolyzing zones ranged from a minimum of 0.75 ± 0.05 cm in fungal isolate NFML3379 to a maximum of 2.03 ± 0.06 cm in NFML3388. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) among the fungal isolates revealed significantly different amylase hydrolyzing zones (F = 155.37; p ≤ 0.001). The hydrolyzing indices varied from 1.36 ± 0.03 in NFML3384 to 2.58 ± 0.11 for the fungal isolate NFML3374. Two fungal isolates (NFML3424 and NFML3381) were identified as Aspergillus candidus and A. flavus while 9 fungal isolates were identified as different species of Penicillium. One fungal isolate (NFML3379) was unable to identify due to absence of spores and designated as sterile hyphae.

Table (4):

Fungal isolates with starch hydrolyzing properties

Isolate ID. |

Fungal species |

Hydrolyzing zone(cm ± SD) |

Hydrolyzing Index (±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

NFML3379 |

Sterile hyphae |

0.75 ± 0.05 |

1.39 ± 0.03 |

NFML3424 |

Aspergillus candidus |

0.83 ± 0.06 |

1.57 ± 0.05 |

NFML3384 |

Penicillium decumbens |

0.85 ± 0.05 |

1.36 ± 0.03 |

NFML3386 |

Penicillium citrinum |

0.98 ± 0.06 |

1.44 ± 0.03 |

NFML3402 |

Penicillium simplicissimum |

1.03 ± 0.04 |

1.46 ± 0.02 |

NFML3431 |

Penicillium chrysogenum |

1.08 ± 0.06 |

1.46 ± 0.03 |

NFML3393 |

Penicillium simplicissimum |

1.33 ± 0.06 |

1.73 ± 0.04 |

NFML3381 |

Aspergillus flavus |

1.42 ± 0.08 |

1.83 ± 0.07 |

NFML3451 |

Penicillium spinulosum |

1.62 ± 0.08 |

2.13 ± 0.11 |

NFML3401 |

Penicillium chrysogenum |

1.63 ± 0.03 |

1.87± 0.02 |

NFML3374 |

Penicillium chrysogenum |

1.95 ± 0.09 |

2.58 ± 0.11 |

NFML3388 |

Penicillium chrysogenum |

2.03 ± 0.06 |

2.45 ± 0.04 |

Values are means of triplicate analyses with standard deviation (±SD)

Figure 5. Fungal isolate T107 (NFML3384), T182 (NFML3393) and T217 (NFML3401) showing amylase hydrolyzing activities on SA plates (A-C). Red arrows indicate halo/clear zones on SA plates due to amylase activity

Hydrolyzing activity and index of protease enzymes on SMA plates

Protease enzyme breaks down the protein casein producing a clear zone around the fungal colonies on SMA plates (Figure 6). The presence of hydrolyzing zones (clear zones) around the fungal colonies were measured to determine hydrolyzing zones and indices. Among 25 fungal isolates, highest enzyme hydrolyzing zone was shown by NFML3424 (1.12 ± 0.03 cm) followed by NFML3381 (0.98 ± 0.08) while the lowest hydrolyzing zone (0.17 ± 0.06 cm) was recorded from the fungal isolate NFML3428 (Table 5). The highest hydrolyzing index was shown by NFML3381 (2.74 ± 0.21) and the lowest was recorded in NFML3407 (1.11 ± 0.03). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) among the fungal isolates revealed significantly different protease hydrolyzing zones (F = 28.48; p ≤ 0.001). Nine of the fungal isolates showing protease production were identified as Penicillium, 4 isolates were Aspergillus, and 1 isolate each was identified as Beauveria, Fusarium and Trichosporon. Three (3) of the fungal isolates were sterile hyphae while 6 fungal isolates could not be identified and designated as unidentified fungi. The fungal isolate showing highest protease activity indices were Aspergillus flavus (2.74), Penicillium simplicissimum (2.48) and P. jensenii (2.10).

Table (5):

Fungal isolates showing protein hydrolyzing properties

Isolate ID |

Fungal species |

Hydrolyzing zone (cm ± SD) |

Hydrolyzing Index (±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

NFML3428 |

Fusarium sp. |

0.17 ± 0.06 |

1.17 ± 0.06 |

NFML3407 |

Beauveria sp. |

0.20 ± 0.05 |

1.11 ± 0.03 |

NFML3410 |

Unidentified fungus 3 |

0.23 ± 0.03 |

1.14 ± 0.02 |

NFML3386 |

Penicillium citrinum |

0.25 ± 0.05 |

1.55 ± 0.18 |

NFML3393 |

Penicillium simplicissimum |

0.27 ± 0.03 |

1.55 ± 0.05 |

NFML3443 |

Trichosporon sp. |

0.27 ± 0.08 |

1.27 ± 0.08 |

NFML3434 |

Aspergillus fumigatus |

0.35 ± 0.05 |

1.26 ± 0.04 |

NFML3409 |

Unidentified fungus 2 |

0.35 ± 0.10 |

1.26 ± 0.08 |

NFML3406 |

Unidentified fungus 1 |

0.38 ± 0.03 |

1.35 ± 0.03 |

NFML3420 |

Unidentified fungus 5 |

0.38 ± 0.08 |

1.24 ± 0.05 |

NFML3415 |

Unidentified fungus 4 |

0.40 ± 0.05 |

1.52 ± 0.08 |

NFML3388 |

Penicillium jensenii |

0.40 ± 0.09 |

2.10 ± 0.42 |

NFML3451 |

Penicillium spinulosum |

0.43 ± 0.03 |

1.41 ± 0.04 |

NFML3403 |

Sterile hyphae |

0.45 ± 0.05 |

1.30 ± 0.03 |

NFML3422 |

Unidentified fungus 6 |

0.45 ± 0.10 |

1.32 ± 0.08 |

NFML3404 |

Sterile hyphae |

0.52 ± 0.03 |

1.23 ± 0.01 |

NFML3431 |

Penicillium chrysogenum |

0.52 ± 0.08 |

1.72 ± 0.13 |

NFML3435 |

Penicillium citrinum |

0.57 ± 0.06 |

1.42 ± 0.06 |

NFML3401 |

Penicillium roqueforti |

0.63 ± 0.03 |

1.67 ± 0.06 |

NFML3402 |

Penicillium simplicissimum |

0.75 ± 0.05 |

2.48 ± 0.31 |

NFML3426 |

Penicillium citrinum |

0.75 ± 0.10 |

1.48 ± 0.07 |

NFML3427 |

Aspergillus candidus |

0.87 ± 0.03 |

1.54 ± 0.03 |

NFML3441 |

Sterile hyphae |

0.88 ± 0.06 |

1.55 ± 0.05 |

NFML3381 |

Aspergillus flavus |

0.98 ± 0.08 |

2.74 ± 0.21 |

NFML3424 |

Aspergillus candidus |

1.12 ± 0.03 |

1.74 ± 0.02 |

Values are means of triplicate analyses with standard deviation (±SD)

Application of enzymes in food, detergent, pharmaceuticals, textiles, etc. have been increased in order to achieve sustainable production and their applications in various industries, pharmaceutical and domestic purposes. Exploratory studies for discovery of enzyme from highly efficient microbial strains (bacteria and fungi) are in progress at a rapid rate. Production of extracellular enzymes (amylase, cellulase and protease) were screened from filamentous fungi isolated from different forest soils of Arunachal Pradesh, North Eastern India. The study observed presence of extracellular enzyme activities in 31 of the 85 filamentous fungal isolates as shown by presence of hydrolyzing zones (halo zones) on the selective culture media plates. The number of fungal isolates showing protease hydrolyzing properties was found to be higher (25 isolates) than amylase (12 isolates) and cellulase enzymes (10 isolates). Penicillium (9 species) and Aspergillus (4 species) were most dominant fungi with highest number of species capable of producing the three enzymes in respective culture media plates. Beauveria, Fusarium and Trichosporon with one isolate each were also identified in this study. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed statistically significant variation of enzyme hydrolyzing zones among fungal isolates for cellulase, amylase and protease.

The highest cellulase hydrolyzing index was shown by Pupureocillium sp. in this study. Production of extracellular enzymes like cellulase, chitinase and protease from P. lilacinum have been reported previously while production of cellulase enzymes by this fungus is scarcely reported.20-23 In this study, the hydrolyzing index of Pupureocillium was found higher than Trichoderma sp.24 and similar to that of Humicola sp.25 The reported hydrolyzing index of cellulase observed in this study was lower than Aspergillus sydowii reported from another study.25 Penicillium chrysogenum has been reported as one of the efficient strain of fungi with highest amylase activity under solid state and submerged fermentation processes.26-29 The hydrolyzing zone and hydrolyzing index of P. chrysogenum recorded in this study was significantly higher than reports of other studies.5,30 This fungal species has also been reported to show high alpha-amylase production in solid state fermentation as indicated by highest clearing zone and starch hydrolysis.31 The maximum hydrolyzing index of protease was shown by Aspergillus flavus. This fungus has been reported to cause food spoilage and production of aflatoxin.32 Enhanced production of protease by A. flavus as comparison to A. fumigatus and A. terreus has been reported in other studies.33,34 The hydrolyzing index shown by A. flavus in the present study was found to be higher than the enzyme index reported from other species of Aspergillus spp.35,36 Studies on protease production using commercial detergents and solid state fermentation have reported to enhance quantity of protease production by A. flavus.37,38 The two fungi, P. citrinum and A. flavus have been reported to produce high amounts of alpha-amylase, cellulase and protease enzymes under different growth conditions. In this study, four species of fungi, A. flavus, P. citrinum, P. chrysogenum and P. simplicissimum were found to produce three industrially important enzyme, cellulase, amylase and protease as revealed by significantly high hydrolyzing zones and indices. These fungi may be investigated further for characterization and quantification of enzyme activities and commercial applications.

The present study aimed to isolate and identify filamentous fungi with high potential for production of three industrially important enzymes, amylase, cellulase and protease. Based on the present study it was observed that several species of filamentous fungi are capable of producing three industrially important enzymes. The fungal isolate, Purpureocillium sp. (NFML3448) has shown highest cellulase hydrolyzing zone and index. Penicillium chrysogenum (NFML3388 and NFML3374) showed highest starch hydrolyzing zone and index. A. candidus (NFML3424) and Aspergillus flavus (NFML3381) showed highest protease hydrolyzing zones and indices. Four species of filamentous fungi, A. flavus, P. citrinum, P. chrysogenum and P. simplicissimum were found to show all three enzyme activities. Further studies on optimization of culture media of the selected species of filamentous fungi could lead to large scale production of the three important enzymes for commercial applications.

Additional file: Table S1 and Figure S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Principal Chief Conservator of Forest (PCCF), Officials and Technical Staffs, Department of Forest, Environment and Climate Change, Government of Arunachal Pradesh, India, for permission to visit and collect soil samples and their cooperation and assistance during field visits in different districts of the state for the research work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

This study was funded by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, vide Grant No. DBT/PR12956/NDB/39/504/20156.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This article does not contain any studies on human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

- Li S, Yang X, Yang S, Zhu M, Wang X. Technology prospecting on enzymes: application, marketing and engineering. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2012;2(3):e201209017.

Crossref - Kumar A, Dhiman S, Krishan B, et al. Microbial enzymes and major applications in the food industry: a concise review. Food Prod, Process and Nutr. 2024;6(1):85.

Crossref - Chandel AK, Rudravaram R, Rao LV, Ravindra P, Narasu ML. Industrial enzymes in bioindustrial sector development: an Indian perspective. J Commer Biotechnol. 2007;13:283-91.

Crossref - Maravi P, Kumar A. Optimization and statistical modeling of microbial cellulase production using submerged culture. J Appl Biol Biotechnol. 2021;(2):142-152.

Crossref - Saleem A, Ebrahim MK. Production of amylase by fungi isolated from legume seeds collected in Almadinah Almunawwarah, Saudi Arabia. J Taibah Univ Sci. 2014;8(2):90-97.

Crossref - Naveed M, Nadeem F, Mehmood T, Bilal M, Anwar Z, Amjad F. Protease-a versatile and ecofriendly biocatalyst with multi-industrial applications: an updated review. Catal Lett. 2021;151(6):307-323.

Crossref - Solanki P, Putatunda C, Kumar A, Bhatia R, Walia A. Microbial proteases: ubiquitous enzymes with innumerable uses. 3 Biotech. 2021;11(10):428.

Crossref - Singhania RR, Patel AK, Thomas L, Goswami M, Giri BS, Pandey A. Industrial enzymes. Industrial Biorefineries & White Biotechnology. 2015:473-497.

Crossref - Dhyani A, Gururani R, Selim SA, et al. Production of industrially important enzymes by Thermobacilli isolated from hot springs of INDIA. Res Biotechnol. 2017;8:19-28.

Crossref - Berlin A, Gilkes N, Kilburn D, et al. Evaluation of novel fungal cellulase preparations for ability to hydrolyze softwood substrates-evidence for the role of accessory enzymes. Enzyme and Microb Technol. 2005;37(2):175-184.

Crossref - Bhunjun CS, Niskanen T, Suwannarach N, et al. The numbers of fungi: are the most speciose genera truly diverse? Fungal Diversity. 2022;114(1):387-462.

Crossref - Dhevagi P, Ramya A, Priyatharshini S, Thanuja G, Ambreetha S, Nivetha A. Industrially important fungal enzymes: productions and applications. In: Yadav A.N. (eds) Recent Trends in Mycological Research. Fungal Biology. Springer, Cham, 2021;2:263-309.

Crossref - Bairagi S. Isolation, screening and selection of fungal strains for potential cellulase and xylanase production. Int J Pharm Sci Invent. 2016;5(3):2016:1-6.

- Aneja KR. Experiments in Microbiology, Plant Pathology, Tissue Culture and Mushroom Production Technology. New Age International, New Delhi. 2001.

- Sharma AK, Sharma V, Saxena J, Yadav B, Alam A, Prakash A. Isolation and screening of extracellular protease enzyme from bacterial and fungal isolates of soil. Int J Sci Res Environ. Sci. 2015;3(9):0334-0340.

Crossref - Lechuga EG, Zapata IQ, Niסo KA. Detection of extracellular enzymatic activity in microorganisms isolated from waste vegetable oil contaminated soil using plate methodologies. Afr J Biotechnol. 2016;15(11):408-416.

Crossref - Linggi N, Bharti A, Singh SS. Sustainable Management Technique for Recalcitrant Leaf Litter of Mesua Ferrea L. in Avenue Plantations. Current World Environment. 2024;19(1):174.

Crossref - Domsch KH, Gams W, Anderson TH. Compendium of soil fungi. Volume 1. New York: Academic Press.1993.

- Nagamani A, Kunwar IK, Manoharachary C. Handbook of soil fungi. IK International, New Delhi. 2006.

- Girardi NS, Sosa AL, Etcheverry MG, Passone MA. In vitro characterization bioassays of the nematophagous fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum: Evaluation on growth, extracellular enzymes, mycotoxins and survival in the surrounding agroecosystem of tomato. Fungal Biology. 2022;126(4):300-307.

Crossref - Zhang X, Yang Y, Liu L, et al. Insights into the efficient degradation mechanism of extracellular proteases mediated by Purpureocillium lilacinum. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1404439.

Crossref - Srilakshmi A, Gopal DVRS, Narasimha G. Impact of bioprocess parameters on cellulase production by Purpureocillium lilacinum isolated from forest soil. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2017;8(1):B157-B165.

Crossref - Malla MA, Khushk I. Purpureocillium lilacinum: A potent biocontrol agent and cellulase producer. J Fungi. 2019;5(4):91.

- Effiong TE, Abdulsalami MS, Egbe NE, Bakare V. Screening of fungi isolates from soil, pulp waste water and rotten wood for cellulase producing potentials. J Appl Sci Environ Manag. 2019;23(6):1051-1055.

Crossref - James A, Pandya S, Sutaoney P, Joshi VJ, Ghosh P. Isolation and Screening of Potent Cellulolytic Soil Fungi from Raipur City of Chhattisgarh State, India. J Sci Ind Res. 2022;81(11):1173-80.

Crossref - Vidya B, Gomathi D, Kalaiselvi M, Ravikumar G, Uma C. Production and optimization of amylase from Penicillium chrysogenum under submerged fermentation. World J of Pharma Res. 2012;10;1(4):1116-1125.

- Dar GH, Kamili AN, Nazir R, Bandh SA, Jan TR, Chishti MZ. Enhanced production of a-amylase by Penicillium chrysogenum in liquid culture by modifying the process parameters. Microb Pathog. 2015;88:10-15.

Crossref - Silva LD, Gomes TC, Ullah SF, Ticona AR, Hamann PR, Noronha EF. Biochemical properties of carbohydrate-active enzymes synthesized by Penicillium chrysogenum using corn straw as carbon source. Waste Biomass Valor. 2020;11(4):2455-2466.

Crossref - Adeoyo O, Adewumi O. Characterization of a-amylase and antimicrobial activity of Penicillium chrysogenum. J BioSci Biotechnol. 2024;13(1):23-28.

- Balkan B, Aydogdu H, Balkan S, Ertan F. Amylolytic activities of fungi species on the screening medium adjusted to different ph. Erzincan University Journal of Science and Technology. 2012;5(1):1-2.

- Balkan B, Ertan F. Production and properties of a-amylase from Penicillium chrysogenum and its application in starch hydrolysis. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2005;35(2):169-178.

https://doi.org/10.1081/pb-200054740 - Amaike S, Keller NP. Aspergillus flavus. Ann Rev Phytopathol. 2011;49(1):107-133.

Crossref - Oyeleke SB, Egwim EC, Auta HS. Screening of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus fumigatus strains for extracellular protease enzyme production. J Microbiol Antimicrob. 2010;2(7):83-87.

- Chellapandi P. Production and preliminary characterization of alkaline protease from Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus terreus. Journal of Chemistry. 2009;7(2):479-482.

Crossref - Usman A, Mohammed S, Mamo J. Production, Optimization, and Characterization of an Acid Protease from a Filamentous Fungus by Solid State Fermentation. Int J Microbiol. 2021;2021(1):6685963.

Crossref - Maitig AM, Alhoot MA, Tiwari K. Isolation and screening of extracellular protease enzyme from fungal isolates of soil. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2018;12(4):2059-2067.

Crossref - Muthulakshmi C, Gomathi D, Kumar DG, Ravikumar G, Kalaiselvi M, Uma C. Production, purification and characterization of protease by Aspergillus flavus under solid state fermentation. Jordan J Biol Sci. 2011;4(3):137-148.

- Wajeeha AW, Asad MJ, Mahmood RT, et al. Production, purification, and characterization of alkaline protease from Aspergillus flavus and its compatibility with commercial detergents. BioResources. 2021;16(1):291-301.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.