ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

In this research, extracellular fungal extracts containing Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus djamor were used for the removal of erionyl blue A-R (anthraquinone) and solophenyl black FR (azo) textile dyes in artificially contaminated water at 200ppm. For erionyl blue A-R, removals of up to 93.6 and 42.85% were achieved, and for solophenyl black FR of 27 and 31.14%, using the enzymatic extracts of P. ostreatus and P. djamor respectively. Enzymatic activity values of 888.41 IU and 152.22 IU were reached for the laccases obtained from the submerged culture extract of Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus djamor respectively. The extract obtained from P. ostreatus was partially purified using dialysis and anion exchange chromatography (DEAE), by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. A molecular mass of 67 kDa was determined.

Pleurotus, dye, laccase, enzyme.

The textile industry is one of the main sources of pollution, it discharges effluents containing a wide variety of dyes, the most important ones are the azoids and the anthraquinones and therefore constitute the largest group of all organic dyes on the market1, 2.

The toxicity of azo acids is because they produce aromatic amines during natural processes of degradation3-6. In addition, azo dyes affect water quality by preventing the passage of light and by increasing the demand of chemical oxygen. In contrast, there is little information on the biodegradation of anthraquinone dyes7.

The “maquilas” or laundries, as they are called locally in the State of Puebla, are responsible for the discoloration, bleaching or dyeing of the denim. They are mainly located in community dwellings such as San Rafael Tenanyecac, Villa Alta, San Mateo Ayecac and Santa Ana Xalmimilulco,8 which requires a large amount of water use, which at the end of the process contains, in addition to the dyes, chemical additives used to treat the garments and give them different finishes. Therefore, the wastewater they produce contains various chemical pollutants that are discharged to municipal drainage or irrigation canals most of the time, without treatment or with inadequate treatments, which eventually flow into the Atoyac River. In order to contribute to this problem, the use of ligninolytic fungi such as those of the genus Pleurotus capable of synthesizing a complex of extracellular enzymes, mainly peroxidases and Laccases (p-diphenol: dioxygen: oxide-reductase) these are extracellular glycoproteins containing copper and a molecular weight between 60 and 80 kDa, have the capacity to reduce molecular oxygen to two molecules of water and simultaneously work in the oxidation of many aromatic substrates9. The range of oxidizable substrates is broad and includes pentachlorophenol, 2,6-dimethoxyphenol aromatic amines and other easily oxidizable aromatic compounds, as well as azo dyes10, 11.

The production of laccase enzymes was carried out by submerged culture, using a mineral medium consisting of magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (J.T.Baker ®) ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (J.T.Baker ®) manganese sulfate (J.T.Baker ®), sodium chloride (J.T.Baker ®), ammonium sulfate (J.T.Baker ®), potassium phosphate dibasic (J.T.Baker ®) and as carbon source wheat bran at a pH of 6.2 and inoculated with 4 units of 1cm2 of PDA (BD Bioxon ®) with the strains of P. ostreatus and P. djamor of the ceparium of the Department of Research in Agricultural Sciences of the Institute of Sciences of the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, it was incubated at 28°C and a stirring speed of 120rpm. Monitoring of laccase activity was performed on the seventh day using 2,22 -Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (Sigma-Aldrich ®) ABTS as an oxidizable substrate and measuring at a wavelength (l) of 420nm for 1min. using a molar extinction coefficient (e) 36000 M-1cm-1 (12). The enzymatic activity was expressed as international units as a function of volume (IU/ml).

Solutions of water artificially contaminated with the dyes were prepared at 200 ppm erionyl blue A-R (Ciba Specialty Chemicals Inc. ®) and solophenyl black FR (Ciba Specialty Chemicals Inc. ®). To the water artificially contaminated with the dyes to be studied was gradually added the enzymatic extract of laccase, determining the percentage of removal by UV-Vis spectroscopy (Varian Cary 50) all the determinations were made by triplicate-sample method, one of the extracts was subjected to a dialysis process for 15h in 20mM phosphate buffer, at a pH of 7.4 and at a temperature of 4°C, once the time was over, the dialysate was centrifuged at 7500rpm for 20min, then anion exchange chromatography was performed with the pre-equilibrated Diethylaminoethyl (DE-53 Whatman) resin at a pH of 7.4. The proteins obtained were eluted with 100ml of 20mM phosphate buffer – 1M NaCl, at a pH of 7.4, for determination of the molecular mass, was performed by electrophoresis in 12% concentration polyacrylamide gel, where 15 µl of the extract were added and let it run at 120V / 2.30h.

The maximum enzymatic activity obtained for the laccase produced by P. ostreatus was 888.41 IU/ml and for P. djamor 153.22 IU/ml. With these enzymatic extracts, it was possible to remove the dyes studied in the percentages reported in Table 1.

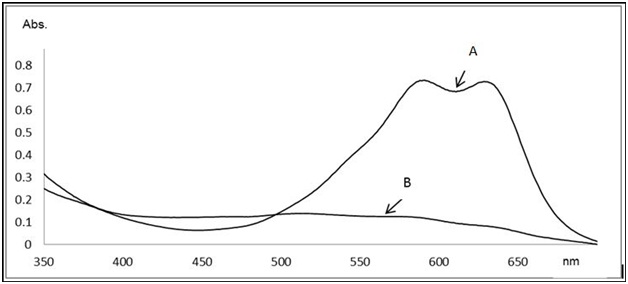

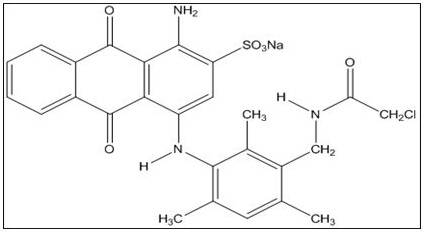

In figure 1, the UV-Vis spectra of the erionyl blue dye A-R are presented before and after the reaction. In this research using the P. ostreatus extract, it was possible to remove 93.77% of the dye erionyl blue A-R (Figure 2), classified as acid blue 260 with CAS number 62168-86-9 and molecular formula C26H23ClN3NaO6S, molecular mass of 563.96g / mol and belongs to the family of anthraquinones13.

Fig. 1: Spectrum of UV-Vis absorption of water artificially contaminated with erionyl blue A-R dye at 200 ppm and treated with Pleurotus ostreatus. A) Untreated water b) Treated water

Fig. 1: Spectrum of UV-Vis absorption of water artificially contaminated with erionyl blue A-R dye at 200 ppm and treated with Pleurotus ostreatus. A) Untreated water b) Treated water Fig. 2: Erionyl Blue A-R

Fig. 2: Erionyl Blue A-ROn the other hand, Sánchez-López14 demonstrated the ability of the enzyme extract (laccase and manganese peroxidase) from Trametes maxima strain MUCL 44155 to remove acid blue anthraquinone dye 62 by 91% measured at 630 nm. Other fungi such as Thanatephorus cucumeris have been used to degrade anthraquinone dyes as the blue reactive dye 5 by DyP peroxidase having percentages above 90% measured at 630 nm15. In Japan, Itoh et. al.16 have used the white rot fungus Coriolus versicolor to degrade violet dye 12 (4-dihydroxyanthraquinone).

The UV/Vis absorption spectra of the reaction products (Figure 1) showed an increase in absorbance from 520 nm and towards the ultraviolet region behavior very similar to those reported by Sánchez-López14 and Sugano15. With regard to the Pleurotus djamor strain, lower removal values were observed with respect to P. ostreatus (Table 1).

Table (1):

Percentage of removal of the studied dyes.

Colorant |

Wavelength |

P. ostreatus |

P. djamor |

|---|---|---|---|

Erionyl Blue A-R |

630 |

93,67 |

42.85 |

Solophenyl Black FR |

490 |

27.00 |

31.14 |

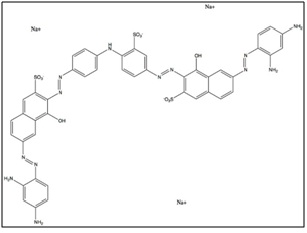

The solophenyl black dye (direct black 22) is classified as Index 35435, indicating that it is a polyazo dye. (17, 18) its structure is reported in figure 3. With respect to the oxidation of azo dyes like the solophenyl black FR by laccases and peroxidases, several authors report the formation of naphthoquinones19-22. In contrast, Mohana et al23 report that using a microbial consortium applied in the treatment of water contaminated with direct black 22 (solophenyl black), obtained as degradation products 1-naphthol and diphenylamine as a product of anaerobic reduction, similar results obtained by Chávez24, but using microbial consortia isolated from the Alseseca River of the City of Puebla, Mexico, these products are toxic so it would be convenient to use oxidation mechanisms with laccases or peroxidases and not chemical reduction. Although the removal rates for this azo-type dye were low (Table 1), it is important to emphasize that in this case, the laccases of the strain Pleurotus djamor were more efficient than those of Pleurotus ostreatus. In addition, for wastewater treatment it is convenient to use a treatment train for the process to be efficient. It has been reported that ligninolytic enzymes produced by Basidiomycetes of the genus Trametes remove better the dyes of an anthraquinone nature than the azo25, 26, as found in this research.

Fig. 3: Solophenyl Black FR

Fig. 3: Solophenyl Black FRThe partially purified enzyme had a molecular mass of 67 kDa as determined by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. It has been reported that most of these enzymes range from 50-70 kDa27, 28.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to Programa para el Desarrollo Professional Docente (PRODEP) for supporting the generation and application of knowledge: Folio BUAP-PTC-449 and agreement number DSA/103-5/16/10420

- Board, N. The Complete Technology Book on Dyes & Dye Intermediates. Delhi: National Institute of Industrial Research; 2003. p. 730.

- Gregory, P. Dyes and Dye Intermediates. Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2000.

- Weisburger, J.H. Comments on the history and importance of aromatic and heterocyclic amines in public health. Mutat Res. 2002; 506-507:9-20.

- Sandhya, S. Biodegradation of Azo Dyes Under Anaerobic Condition: Role of Azoreductase. In: Atacag Erkurt H, editor. Biodegradation of Azo Dyes. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2010. p. 39-57.

- Golka, K., Kopps, S., Myslak, Z.W. Carcinogenicity of azo colorants: influence of solubility and bioavailability. Toxicol Lett. 2004; 151(1):203-10.

- Gnanamani, A., Bhaskar, M., Ganga, R, Sekaran, G., Sadulla, S. Chemical and enzymatic interactions of Direct Black 38 and Direct Brown 1 on release of carcinogenic amines. Chemosphere. 2004; 56(9):833-41.

- Sugano, Y., Matsushima, Y., Tsuchiya, K., Aoki, H., Hirai, M., Shoda, M. Degradation pathway of an anthraquinone dye catalyzed by a unique peroxidase DyP from Thanatephorus cucumeris Dec 1. Biodegradation. 2009; 20(3):433-40.

- Juárez, N.H. Allá … donde viven los más pobres : cadenas globales, regiones productoras, la industria maquiladora del vestido Humberto Juárez Núñez. Mexico, D.F 2004. 279 p.

- Gianfreda, L., Xu, F., Bollag J.M. Laccases: A Useful Group of Oxidoreductive Enzymes. Bioremediation Journal. 1999; 3(1):1-26.

- Davila, G., Vázquez-Duhalt, R. Enzimas ligninolíticas fúngicas para fines ambientales. Mensaje Bioquímico. 2006; 30:29-55.

- Hublik, G., Schinner, F., Characterization and immobilization of the laccase from Pleurotus ostreatus and its use for the continuous elimination of phenolic pollutants. Enzyme and microbial technology. 2000; 27(3-5):330-6.

- Revollo, E., Serna, O., Hernández, J. Actividad lacasa en Tsukamurella sp y Cellulosimicrobium sp. Revista Colombiana de Biotecnología. 2012; 14(2):70-80.

- Dimacolor G. Acid brilliant blue rl(acid blue 260) technical data sheet 2014 [Available from: http://www.dimacolorgroup.com/product_detail_en/id/142.html.

- Sánchez- López, M.I., Guerra, G., Ramos- Leal, M., Arguelles, J., Domínguez, O., Torres, G., Hechevarria, Y., Manzano, A.M. Estabilidad y actividad enzimática del crudo enzimático del cultivo de Trametes maxima, decoloración in vitro de colorantes sintéticos Revista CENIC Ciencias Biológicas. 2010:1-13.

- Sugano, Y., DyP-type peroxidases comprise a novel heme peroxidase family. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009; 66(8):1387-403.

- Itoh, K., Kitade, Y., Yatome, C. Oxidative biodegradation of an anthraquinone dye, pigment violet 12, by Coriolus versicolor. Bulletin of environmental contamination and toxicology. 1998; 60(5):786-90.

- Novact C. Allied direct black vsf 1200%. 2017 [Available from: http://www.novact.info/id53.html.

- Bestchem. Product Information product #7565 solophenyl black FR 2017 [Available from: https://bestchem.hu/bestchem/en/surplus/product/7565.

- Spadaro, J.T., Renganathan, V. Peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of azo dyes: mechanism of disperse Yellow 3 degradation. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 1994; 312(1):301-7.

- Goszczynski, S., Paszczynski, A., Pasti-Grigsby, M.B., Crawford, R.L., Crawford, D.L. New pathway for degradation of sulfonated azo dyes by microbial peroxidases of Phanerochaete chrysosporium and Streptomyces chromofuscus. Journal of bacteriology. 1994; 176(5):1339-47.

- Chivukula, M., Spadaro, J.T., Renganathan,V. Lignin peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of sulfonated azo dyes generates novel sulfophenyl hydroperoxides. Biochemistry. 1995; 34(23):7765-72.

- López-Díaz, C. Oxidación del tinte azo Orange II mediante MnP en reactores enzimáticos operados en continuo. Santiago de Compostela: Universidad de Santiago de Compostela 2005.

- Mohana, S., Shrivastava S., Divecha J., Madamwar, D. Response surface methodology for optimization of medium for decolorization of textile dye Direct Black 22 by a novel bacterial consortium. Bioresource technology. 2008; 99(3):562-9.

- Bravo, C.E., Valencia, T.J.A., Rivera, E.I., Castaneda, R., and Alonso, C.A. Decolorization of Azo Dye by Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Wastewater. Journal of Pure & Applied Microbiology 2014; 8(2):37-42.

- Claus, H., Faber, G., Konig, H. Redox-mediated decolorization of synthetic dyes by fungal laccases. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2002; 59(6):672-8.

- Abadulla, E., Tzanov, T., Costa, S., Robra K.H., Cavaco-Paulo, A., Gubitz, G.M. Decolorization and detoxification of textile dyes with a laccase from Trametes hirsuta. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2000; 66(8):3357-62.

- Thurston, C.F. The structure and function of fungal laccases. Microbiology. 1994; 140(1):19-26.

- Baldrian, P. Fungal laccases – occurrence and properties. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2006; 30(2):215-42.

© The Author(s) 2017. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.