ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

The study included 234 patients attended to Iben AL-Haithem hospital of ophthalmology in Baghdad city having microbial keratitis , at age of (18-81) years for the period from September 2017- April 2018 . there were 147 ( 63% ) patients with bacterial keratitis and 87 (37%) with fungal keratitis . Men with bacterial keratitis represented 60% (88) and women 40% (59) , while men with fungal keratitis were 61% (53) and women 39% (34), the number of the patients with bacterial keratitis were 82(56%) and 51(59%) with fungal keratitis from Baghdad while the internally displaced were 62(44%) with bacterial and 36(41%) with fungal keratitis , the percentage of patients with bacterial keratitis and fungal keratitis were both (34%) at mean age of 73 ± 2.3 y . Most patients with bacterial keratitis recorded having diabetes mellitus(39%) while the diabetic with fungal keratitis represented (41%) , The results revealed that gram-positive bacteria was 102 (69%) and gram negative 45 ( 31%) , S.aureus was the most common cause of bacterial keratitis42(29%), followed by S.epidermidis 36(24%) then Streptococcus spp. 24(16%), Pseudomonas spp. 17 (12%) , Proteus, spp. 13 (9%), Escherichia coli 9(6%) and Enterobacter spp 6(4%) while Aspergillus fumigates represented 26(30%) as the most common cause of fungal keratitis , Aspergillus flavus 19(22%), Aspergillus niger 16(18%) , Pencillium spp 11(13%), Fusarium oxysporium. 8(9%) , Fusarium solani 5(6%) and Candida spp 2(2%) . S. aureus isolates were susceptible to Cloramphenicol and Ciprofloxacin (83%) while they were resistant to Clindamycin (57%) . S.epidermidis isolates were susceptible to Cloramphenicol and Amikacin (86%) ,Streptococcus spp were susceptible to Tetracycline and Clindamycin (88% ,83%) , Pseudomonas spp showed their high susceptibility to Tetracycline(96%) followed by Cloramphenicol and Ciprofloxacin (88%) both each, Enterobacter spp were susceptible to Tetracycline and Gentamicin (100%) while E.coli were susceptible to Cloramphenicol (100%) followed by Ciprofloxacin and Gentamicin (89%) both, fungal isolates were susceptible to all types of antibiotics used in the study as (98%) of Aspergillus spp isolates were sensitive to Itraconazole (98%) Voriconazole, Amphotericin B and Natamycin (95%,93% ,92%) respectively, Pencillium spp. were sensitive to Amphotericin B (100%) then Natamycin and Itraconazole (91%) both, Fusarium spp were sensitive to Natamycin and Itraconazole (100%), Candida isolates were sensitive (100%) to Amphotericin B, Natamycin and Voriconazole.

Bacterial and fungal keratitis, Antibiotic susceptibility, Ibn Al-Haitham hospital of ophthalmology Baghdad, Iraq

Microbial keratitis is defined as a corneal infection which caused by a range of non-viral pathogens, including bacteria, protists and fungi1. It characterized by pain and corneal ulceration with tissue infiltration,the vision will be affected according to the size and location of the ulcer2.

The climate and socio-economic factors play an important role in the prevalence of each causative organisms, fungal infection is the main cause of corneal blindness ,associated with agricultural injury3. Saprophytic fungi reported as a causative agents and Candida albicans was considered pathogenic in 45.8% of keratitis4. Hosted bacteria might infect the cornea, while the others can be found as normal flora on the lid margin5.

The more virulent bacteria cause corneal destruction and it may be complete in 24-48 hours which will lead to ulceration, abscess, surrounding corneal edema and anterior segment inflammation6.

Ocular surface disease such as trauma, surgery, topical steroid also increased wearing of contact lens and refractive surgery are additional risk factors7 . In Iraq, the common risky factors for microbial keratitis are corneal abrasions, and ocular surface disorders such as dry eye, trichiasis, old scars and most of them are sequels of cicatricial trachoma8.

The study s aimed to determine the prevalence of microbial keratitis infection causatives and determination the susceptibility of the isolates to the most common antibiotics used .

Patients and Methods

This study was conducted in Ibn Al-Haitham hospital of ophthalmology in Baghdad, A total of 234 patients attended the hospital from September 2017- Apri 2018, the patient´s agreement was taken and information documented directly including the socio-demographic characters, age, and history of any disease.

The slit Lamp method was used to record the size and depth of the ulcer and the stromal suppuration. Height of hypopyon if present was also recorded9 .

The scraping was divided into two ports bacterial and fungal detection, blood agar (Himedia, India), chocolate agar, brain heart-infusion agar (Salucea/Germany), MacConkey agar (BDH/England), Sabaroud agar (Biolife /Italy) and Gram reaction. After incubation, positive microbial cultures were further biochemical reaction were done to identified the species as most Staphylococcus spp. and Pseudomonas spp. were identified by API system (bio Merieux)10.

lacto phenol–cotton blue stain was used for examination of hyphae and spore morphological identification under the microscope11.

Antibiotic susceptibility

Antibiotic susceptibility was monitored with the disk diffusion assay (Kirby–Bauer), the zone of inhibition was interpreted according to NCCLS guidelines12.

The following antibiotics were tested Erythromycin (15 µg), Clarithromycin (15 µg), Chloramphenicol (30 µg), Clindamycin (2 µg), Tetracycline, (30 µg), Doxycycline (30 µg), Amikacin (30 µg), Gentamicin (10 µg), Ciprofloxacin (5 µg), Ceftriaxone (30 µg) supplied by HiMedia Lab.(India) , reference strains of “Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923, E. coli ATCC25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC27853” were used as a control . Antifungal drugs susceptibility was tested by using CLSI M38-A2 BMD method13. The fungal isolates were tested for susceptibility to four antifungal agents: amphotericin B, natamycin, Itraconazole and voriconazole, “ Candida krusei ATCC 6258 and C . parapsilosis ATCC 22019” were used as a controls .

Statistical Analysis Statistical Analysis

Chi-square test for statistical analysis. A P value <0.05 was used for finding the significance difference between the groups and correlated t-test was used to find the relation between the variables within the same group by using spss program14.

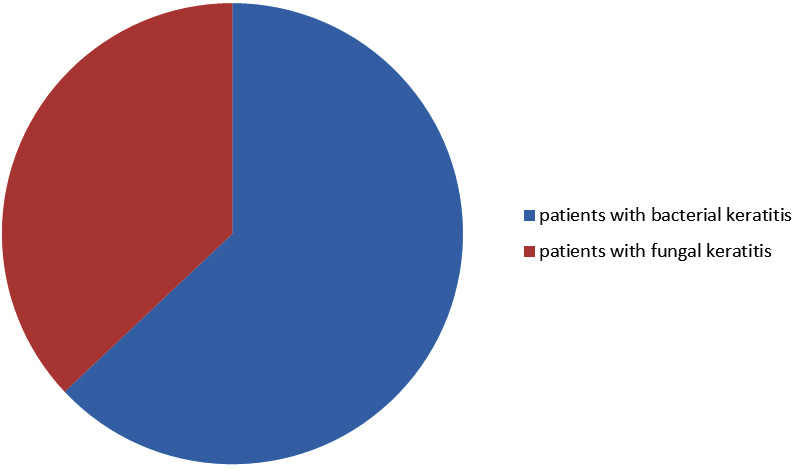

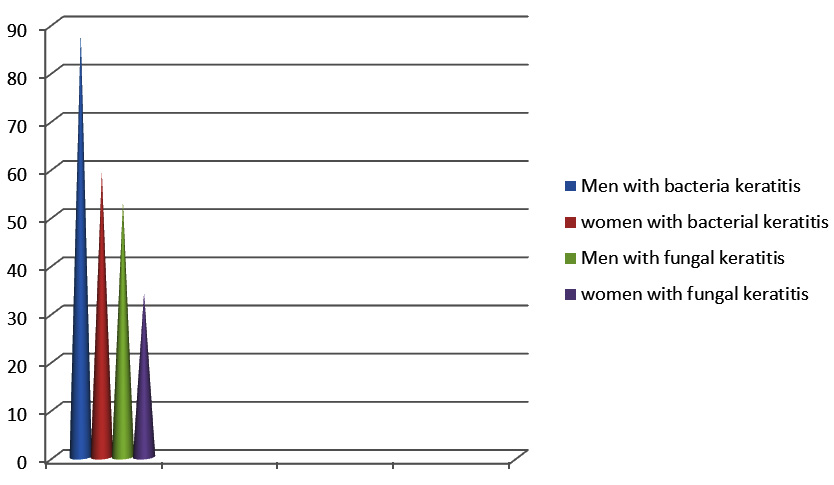

Out of 234 patients having microbial keratitis, there were 147 ( 63% ) patients with bacterial keratitis and 87 (37%) with fungal keratitis as shown in figure 1. Men with bacterial keratitis represented 60% (88) and women 40% (59) ,while men with fungal keratitis were 61% (53) and women 39% (34) as shown in figure 2. The results reveled that the number of the patients with bacterial keratitis were 82(56%) and 51(59%) with fungal keratitis from Baghdad while the internally displaced were 62(44%) and 36(41%) with bacterial and fungal keratitis, there was a significant differences between the two group as shown in table 1.

Fig. 1. Distribution of microbial keratitis among the patients

Fig. 2. Distribution of bacterial and fungal keratitis between men and women

Table (1): Distribution of the patients with bacterial ocular infection according to the Socio-demographic characters.

Socio-demographic characters |

patients with bacterial keratitis |

patients with fungal keratitis |

|---|---|---|

Baghdad |

82(56%) |

51(59%) |

IDP |

62(44%) |

36(41%) |

Total |

147(100%) |

87(100%) |

IDP internally displaced persons, p value (< 0.05)

The results showed that the highest percentage of patients with bacterial keratitis and fungal keratitis were both (34%) at mean age of 73 ± 2.3 y while the lowest percentage of patients with bacterial keratitis was (18%) and with fungal keratitis (15%) at mean age of 25.5± 1.4 y as showed in table 2.Most patients with bacterial keratitis recorded having diabetes mellitus(39%) and the rest of them having arthritis and hypertension (31% ,30%) while the diabetic with fungal keratitis represented (41%) followed by arthritis and hypertension (35%,24%) as showed in table 3.

Table (2):

Disrebution of bacterial and fungal keratitis according to age group.

| Age/years | Mean±SD | Number of patients with bacterial keratitis % | Number of patients with fungal keratitis % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18-33 | 25.5±0.4 | 26(18%) | 13(15%) |

| 34-49 | 41.5±0.6 | 32(22%) | 20(23%) |

| 50-65 | 57.5±0.1 | 38(26%) | 24(28%) |

| 66-81 | 73.5±0.3 | 51(34%) | 30(34%) |

p value (< .05)

Table (3):

Relation between the number of patients with microbial keratitis and history of disease.

History of disease |

Number of patients with bacterial keratitis % |

Number of Patients with fungal keratitis % |

|---|---|---|

Diabetes mellitus |

57(39%) |

36(41%) |

Arthritis |

46(31%) |

30(35%) |

Hypertension |

44(30%) |

21(24%) |

Total |

147(100%) |

87(100%) |

p value (< 0.05)

The results revealed that gram positive bacteria was 102 (69%) while gram negative 45 ( 31%) , S.aureus was the most common cause of bacterial keratitis42(29%), followed by S.epidermidis 36(24%) then Streptococcus spp. 24(16%) , Pseudomonas spp. 17 (12%) , Proteus, spp. 13 (9%) , Escherichia coli 9(6%) and Enterobacter spp 6(4%) while Aspergillus fumigates represented 26(30%) as the most common cause of fungal keratitis , Aspergillus flavus 19(22%), Aspergillus niger 16(18%) , Pencillium spp 11(13%) , Fusarium oxysporium. 8(9%), Fusarium solani 5(6%) and Candida spp 2(2%) as shown table 4.

Table (4):

Profile of isolated bacteria and fungi from patients with keratitis.

Types of isolated bacteria |

Number(%) |

Types of isolated fungi |

Number(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

S.aureus |

42(29%) |

Aspergillus fumigatus |

26(30%) |

S.epidermidis |

36(24%) |

Aspergillus flavus |

19(22%) |

Streptococcus spp. |

24(16%) |

Aspergillus niger |

16(18%) |

Pseudomonas spp. |

17(12%) |

Pencillium spp. |

11(13%) |

Proteus spp. |

13(9%) |

Fusarium oxysporium |

8(9%) |

Escherichia coli |

9(6%) |

Fusarium solani |

5(6%) |

Enterobacter spp |

6(4%) |

Candida spp |

2(2%) |

Total |

147(100%) |

Total |

87(100%) |

Table (5):

Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance of S. aureus and S.epidermidis isolates.

| Antibiotics | S. aureus n=42 | S.epidermidis n=36 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (µg/ml) | S | I | R | MIC (µg/ml) | S | I | R FRR | |||

| 50 | 90 | 50 | 90 | |||||||

| Erythromycin | 0.25 | 64 | 27(64%) | 2(5%) | 13(31%) | 0.25 | 64 | 30(83%) | 1(3%) | 5(14%) |

| Cloramphenicol | 0.25 | 64 | 35(83%) | 2(5%) | 5(12%) | 0.12 | 64 | 31(86%) | 1(3%) | 4(11%) |

| Clindamycin | 0.06 | 64 | 16(38%) | 2(5%) | 24(57%) | 0.06 | 32 | 29(81%) | 2(6%) | 5(14%) |

| Tetracycline | 1 | 4 | 26(62%) | 1(2%) | 15(36%) | 1 | 4 | 17(47%) | 3(8%) | 16(44%) |

| Amikacin | 0.12 | 32 | 31(74%) | 1(2%) | 10(24%) | 0.25 | 16 | 31(86%) | 2(6%) | 3(8%) |

| Gentamycin | 0,25 | 8 | 29(69%) | 2(5%) | 11(26%) | 0.25 | 16 | 27(75%) | 3(8%) | 7(19%) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 8 | 8 | 35(83%) | 2(5%) | 5(12%) | 8 | 8 | 28(78%) | 2(6%) | 6(17%) |

| Doxycycline | 0.12 | 16 | 34(81%) | 2(5%) | 6(14%) | 0.12 | 16 | 30(83%) | 2(6%) | 4(11%) |

The results of antibiotic susceptibility showed that S. aureus isolates were susceptible to Cloramphenicol and Ciprofloxacin (83%) followed by Doxycycline (81%) and Amikacin (74%) then Gentamycin , Erythromycin and Tetracycline (69%,64% ,62%) , while they were resistant to Clindamycin (57%) .S.epidermidis isolates were susceptible to Cloramphenicol and Amikacin (86%) then Erythromycin and Doxycycline (83%) followed by Clindamycin , Ciprofloxacin and Gentamycin (81% ,78%,75% ) respectively as shown in table 5 .

Table (6):

Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance of Streptococcus spp isolates.

| Antibiotics | Streptococcus spp.n=24 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (µg/ml) | S | I | R | ||

| 50 | 90 | ||||

| Erythromycin | 0.12 | 64 | 18(75%) | 2(8%) | 4(17%) |

| Clarithromycin | 0.25 | 64 | 17(70%) | 2(8%) | 5(21%) |

| Cloramphenicol | 0.25 | 64 | 19(79%) | 1(4%) | 4(17%) |

| Clindamycin | 0.12 | 64 | 20(83%) | 1(4%) | 3(13%) |

| Tetracycline | 0.12 | 64 | 21(88%) | 2(8%) | 1(4%) |

| Doxycycline | 0.25 | 64 | 18(75%) | 2(8%) | 4(17%) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 | 2 | 15(63%) | 3(13%) | 6(25%) |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.5 | 4 | 16(65%) | 1(4%) | 7(29%) |

Streptococcus spp isolates were susceptible to Tetracycline and Clindamycin (88% ,83%) then Cloramphenicol (79%) followed by Erythromycin and Doxycycline (75%) both as shown in table 6.

Pseudomonas spp isolates showed their high susceptibility to Tetracycline(96%) followed by Cloramphenicol and Ciprofloxacin (88%) both and Amikacin,Doxycycline and Gentamycin(82%) each of them as shown in table 7.

Table (7):

Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance of Pseudomonas spp isolates.

| Antibiotics | Pseudomonas spp. n=17 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (µg/ml) | S | I | R | ||

| 50 | 90 | ||||

| Amikasin | 8 | 32 | 14 (82%) | 1(6%) | 2(12%) |

| Cloramphenicol | 1 | 2 | 15(88%) | 1(6%) | 1(6%) |

| Tetracycline | 8 | 32 | 16 (94%) | 0 | 1(6%) |

| Doxycycline | 1 | 2 | 14(82%) | 1(6%) | 2(12%) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 | 16 | 15(88%) | 1(6%) | 1(6%) |

| Gentamicin | 2 | 8 | 14(82%) | 2(12%) | 1(6%) |

The results showed that Enterobacter spp isolates were susceptible to Tetracycline and Gentamicin (100%) followed by Ciprofloxacin (83%) while E.coli isolates were susceptible to Cloramphenicol (100%) followed by Ciprofloxacin and Gentamicin (89%) both and they were resistant to Amikacin and Tetracycline (56%) both as shown in table 8.

Table (8):

Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance of Enterobacter spp and E.coli isolates.

| Antibiotics | Enterobacter spp n=6 | E.coli n= 9 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (µg/ml) | S | I | R | MIC (µg/ml) | S | I | R | |||

| 50 | 90 | 50 | 90 | |||||||

| Amikacin | 8 | 32 | 3(50%) | 1(17%) | 2(33%) | 16 | 32 | 4(44%) | 0 | 5(56%) |

| Cloramphenicol | 1 | 2 | 3(50%) | 1(17%) | 2(33%) | 1 | 2 | 9(100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Tetracycline | 8 | 32 | 6(100%) | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 4(44%) | 0 | 5(56%) |

| Doxycycline | 1 | 2 | 3(50%) | 1(17%) | 2(33%) | 1 | 2 | 7(78%) | 0 | 2(22%) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 | 16 | 5(83%) | 1(17%) | 0 | 64 | 64 | 8(89%) | 1(11%) | 0 |

| Gentamicin | 2 | 8 | 6(100%) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 8(89%) | 1(11%) | 0 |

Proteus spp isolates were susceptible to Cloramphenicol and Tetracycline (92%) followed by Ciprofloxacin (85%) and Ceftriaxone and Gentamicin (77%) as shown in table 9.

Table (9):

Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance of Proteus spp isolates.

| Antibiotics | Proteus spp n=13 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (µg/ml) | S | I | R | |||

| 50 | 90 | |||||

| Ceftriaxone | 0.12 | 64 | 10 (77%) | 2(15%) | 1(8%) | |

| Cloramphenicol | 0.25 | 64 | 12(92%) | 1(8%) | 0 | |

| Tetracycline | 8 | 8 | 12(92%) | 1(8%) | 0 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 16 | 16 | 11(85%) | 1(8%) | 1(8%) | |

| Gentamicin | 0.12 | 64 | 10(77%) | 2(15%) | 1(8%) | |

Antifungal susceptibility test showed that (98%) of Aspergillus spp isolates were sensitive to Itraconazole (98%) , Voriconazole , Amphotericin B and Natamycin (95%,93% ,92%) respectively, Pencillium spp. isolates were sensitive to Amphotericin B (100%) then Natamycin and Itraconazole (91%) both followed by Voriconazole (82%) , as shown in table 10 .

Table (10):

Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance of Aspergillus spp and Pencillium spp isolates.

| Antifungal | MIC (µg/ml) | Aspergillus spp. n= 61 | Pencillium spp. n= 11 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | I | R | S | I | R | |||

| 50 | 90 | |||||||

| Amphotericin B | 2 | 4 | 57(93%) | 1(2%) | 3(5%) | 11(100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Natamycin | 32 | 32 | 56(92%) | 2(3%) | 3(5%) | 10(91%) | 1(9%) | 0 |

| Itraconazole | 0.125 | 0.25 | 60(98%) | 1(2%) | 0 | 10(91%) | 1(9%) | 0 |

| Voriconazole | 0.25 | 0.5 | 58(95%) | 1(2%) | 2(3%) | 9(82%) | 2(18%) | 0 |

Fusarium spp isolates were sensitive to Natamycin and Itraconazole (100%) then Amphotericin B and Voriconazole (92%) both as shown in table 11 .

Table (11):

Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance of Fusarium spp.

| Antifungal | Fusarium spp. n= 13 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (µg/ml) | S | I | R | ||

| 50 | 90 | ||||

| Amphotericin B | 2 | 4 | 12(92%) | 1(8%) | 0 |

| Natamycin | 32 | 32 | 13(100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Itraconazole | 0.125 | 0.25 | 13(100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Voriconazole | 0.25 | 0.5 | 12(92%) | 1(8%) | 0 |

Table (12):

Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance of Candida spp isolates.

| Antifungal | Candida spp. n= 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (µg/ml) | S | I | R | ||

| 50 | 90 | ||||

| Amphotericin B | 2 | 4 | 2(100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Natamycin | 32 | 32 | 2(100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Itraconazole | 0.125 | 0.25 | 1(50%) | 1(50%) | 0 |

| Voriconazole | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2(100%) | 0 | 0 |

The results reveled that Candida isolates were sensitive mostly to all types of the antibiotics were used in the study as showed in table 12.

Our study revealed that patients with bacterial keratitis were represented (63%) from the total patients with microbial keratitis, men represented the highest levels (60%) while fungal keratitis patients were (37%) and men represented (61%) of them The relatively highest percentage of males with microbial keratitis as a compression with females seen almost closely to some other studies15,16. According to the socio-demographic characters , the number of patients with microbial keratitis from Baghdad represented (57%) while the internally displaced were (43%) and this might be related to unsuitable health conditions or inappropriate life issues .

There was high percentage of patients with microbial keratitis at mean age of 73.5±0.3 and gradually decreases and these fining are different in other study in Baghdad , as the patients group (41-59) years were the most microbial keratitis infected with a percentage of (30.20 %), while the lowest infected (e” 60) year with a percentage of (17.80 %) and another study in south India they found that the age range of 41–60 years was more affected , this may be due to choosing of the common causes of infection17 ,18 . The patients with bacterial keratitis recorded with diabetes mellitus were (39%) and the rest were having arthritis and hypertension (31% ,30%) while the diabetic with fungal keratitis were (41%) followed by arthritis and hypertension (35%,24%) and these results disagree with other findings depending on the age and other chronic disease due to health style (food and environment)19,20 . The results revealed that gram positive bacteria was 102 (69%) and gram negative 45 ( 31%) , S.aureus was the most common cause of bacterial keratitis42(29%), followed by S.epidermidis 36(24%) then Streptococcus spp. 24(16%) , Pseudomonas spp. 17 (12%) , Proteus, spp. 13 (9%) , Escherichia coli 9(6%) and Enterobacter spp 6(4%) while the most common causes of fungal keratitis were Aspergillus fumigates 26(30%), Aspergillus flavus 19(22%) , Aspergillus niger 16(18%) , Pencillium spp 11(13%) , Fusarium oxysporium. 8(9%) , Fusarium solani 5(6%) and Candida spp 2(2%) , these were agreed with other study in Baghdad as gram-positive isolates were (81.1%) from the total cases and Staphylococcus spp. was the most common isolates, Pseudomonas spp. was the first among gram-negative isolates21. Other study conducted in Ibn Al-Hiatham Teaching Eye Hospital at 2003, found that Pseudomonas spp. was the most common bacterial isolates, followed by Staphylococcus spp. and fungal growth was detected in 13 cases22 Other study founded coagulase negative staphylococci were the most common may be related to the variation to different climatic conditions, socioeconomic variables23. Another study found that the fungal growth represented (18.7%), and Aspergillus spp. was 42 (56.8%) followed by Fusarium spp. 20 (27%), Pencillium spp. 4 (5.4%), Scopulariopsis spp. 2 (2.7%), Geotrichum spp. 1 (1.4%), Alternaria spp. 1 (1.4%) and Candida spp. 4 (5.4%)24. other investigation found that the prevalence of fungal keratitis in Iraq the most common fungus isolated was Aspergillus spp. then Fusarium spp. , Candida albicans and Scopulariopsis spp25. Our results reveled that gram positive and negative bacterial isolates were susceptible to the most antibiotics used as S. aureus isolates were susceptible to Cloramphenicol and Ciprofloxacin (83%) followed by Doxycycline (81%) , while they were resistant to Clindamycin (57%) .S.epidermidis isolates were susceptible to Cloramphenicol and Amikacin (86%) . Streptococcus spp isolates were susceptible to Tetracycline and Clindamycin (88%, 83%), Pseudomonas spp isolates showed their high susceptibility to Tetracycline(96%) followed by Cloramphenicol and Ciprofloxacin (88%) and these were agreed with other studies in China and Iran26 ,27. Enterobacter spp isolates were susceptible to Tetracycline and Gentamicin (100%) while E.coli isolates were susceptible to Cloramphenicol (100%) but they were resistant to Amikacin and Tetracycline (56%) both, however, Proteus spp isolates were susceptible to Cloramphenicol and Tetracycline (92%) and theses findings were recorded in many other studies28,29. fungal isolates showed high susceptibility as Aspergillus spp isolates were sensitive to Itraconazole (98%) , Voriconazole then Amphotericin B and Natamycin (95%,93% ,92%) respectively , Pencillium spp. isolates were sensitive to Amphotericin B (100%) then Natamycin and Itraconazole (91%) both while Fusarium spp isolates were sensitive to Natamycin and Itraconazole (100%) then Amphotericin B and Voriconazole (92%) both and Candida isolates were sensitive to the most antibiotics that used in the study ,these results were matching to many other results in the same field30,31.

Keratitis was very clear among the patients with ocular bacterial infections. S. aureus was the highest gram positive bacterial isolates followed by S.epidermids while gram negative dominant isolates were Pseudomonas spp. Aspergillus spp recorded high prevalence followed by Pencillium spp. Gram positive and negative isolates as well fungal isolates were susceptible to the most common tested antibiotics which will support the treatment strategies and control the common practice of self medication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

- Zhang W, Yang H, Jiang L, Han L, Wang L. Use of potassium hydroxide, Giemsa and calcofluor white staining techniques in the microscopic evaluation of corneal scrapings for diagnosis of fungal keratitis. J Int Med Res. 2010; 38:1961–67. [PubMed]

- Amrutha KB, Venkatesha D. Microbiological profile of Ulcerative Keratitis in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Res Health Sci 2014; 2: 599 03.

- Sethi S, Sethi MJ, Iqba R. Causes of microbial keratitis in patients attending an eye clinic at Peshawar. Gomal J Med Sci 2010; 8:20 22.

- Insan NG, Mane V, Chaudhary BL, Danu MS, Yadav A, Srivastava V. A review of fungal keratitis: Etiology and laboratory diagnosis. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 2013; 2: 307 14.

- Itahashi, M. ; Higaki, S. ; Fukuda, M. and Shimomura, Y. Detection and Quantification of Pathogenic Bacteria and Fungi Using Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction by Cycling Probe in Patients With Corneal Ulcer. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010; 5: 535-40 .

- Hua, X.; Yuan, X. and Wilhelmus, K. R. A fungal PH- responsive dignaling pathway regulating Aspergillus adaptation and invasion into the cornea. IOVS 2010; 3:51.

- Kumara,; Pandy, S.; Madan, M. ; Kavathia, G. Keratomycosis with Superadded Bacterial Infection Due To Corticosteroid Abuse-A Case Report. J Clini Diag Res. 2010; 4:2918-21.

- Fawzy, G.; Al-Taweel, A. and Melake, N. In Vitro Antimicrobial and Anti-Tumor Activities of Intracellular and Extracellular extracts of Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus flavus var. columinaris. J Pharm 2011; 1:980-87.

- Al-Yousaf, N. Microbial Keratitis in Kingdom of Bahrain: Clinical and Microbiology study. Middle East African J Ophthal. 2009; 16: 3-7.

- Faiz I Al-Shakarchi Initial therapy for suppurative microbial keratitis in Iraq. J Ophthalmol 2007; 91:1583–87.

- Hemavathi, P. Sarmah, and P. Shenoy, Profile of microbial isolates in ophthalmic infections and antibiotic susceptibility of the bacterial isolates: a study in an eye care hospital, Bangalore. J Clini Diag Res 2014; 8: 23–25.

- Shimizu Y, Toshida H. Honda R et al., Prevalence of drug resistance and culture-positive rate among microorganisms isolated from patients with ocular infections over a 4-year period. J Clini Ophthalm, 2013; 7: 695–02.

- Willcox M, Sharma S, Naduvilath T.J, Sankaridurg P.R., Gopinathan U.and Holden B. A. External ocular surface and lens microbiota in contact lens wearers with corneal infiltrates during extended wear of hydrogel lenses, J Clini Ophthalm 2011; 37(2): 90–95.

- Li Y.”Microbial spectrum and resistance patterns of ocular infection in Tianjin Eye Hospital (2005–2009),” Shandong Medicine. 2010; 50: 65–66.

- Giardini F., Grandi G. , De Sanctis U. et al., “In vitro susceptibility to different topical ophthalmic antibiotics of bacterial isolates from patients with conjunctivitis,” Ocul Immunol Inflam. 2011; 19: 419–21,

- Torres I. M., Bento E. B.,. Almeida L. D. , de S´a L. Z. and Lima E. M. , Preparation, characterization and in vitro antimicrobial activity of liposomal ceftazidime and cefepime against Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains Brazilian J Micro 2012 ; 43: 984–92.

- Mehta S., Mansoor H., Khan S., Saranchuk P., and Isaakidis P. Ocular inflammatory disease and ocular tuberculosis in a cohort of patients co-infected with HIV and multidrugresistant tuberculosis inMumbai, India: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infec Dis. 2013; 13: 225.

- Chen X. and Adelman R. A., Microbial spectrum and resistance patterns in endophthalmitis: a 21-year (1988–2008) review in Northeast United States. J Oculr Pharmacol and Ther. 2012; 28: 329–34.

- Jain R.,.Murthy S., and.Motukupally S. R,”Clinical outcomes of corneal graft infections caused by multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa,” Cornea, 2014; 33: 22–26.

- Deren YT, Ozdek S, Kalkanci A, Akyürek N, Hasanreisolu B. Comparison of antifungal efficacies of moxifloxacin, liposomal amphotericin B, and combination treatment in experimental Candida albicans endophthalmitis in rabbits. Can J Microbiol 2010; 56: 1-7

- Sun B, Li ZW, Yu HQ, Tao XC, Zhang Y, Mu GY. Evaluation of the in vitro antimicrobial properties of ultraviolet A/riboflavin mediated crosslinking on Candida albicans and Fusarium solani. Int J Ophtalmol 2014; 7: 205-210.

- Borkar DS. Acanthamoeba, fungal, and bacterial keratitis: a comparison of risk factors and clinical features. Am J Ophthalmol 2014; 157: 56-62

- Lalitha P, Sun CQ, Prajna NV, Karpagam R, Geetha M, O’Brien KS, Cevallos V, McLeod SD, Acharya NR, Lietman TM; Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial Group. In vitro susceptibility of filamentous fungal isolates from a corneal ulcer clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2014; 157: 318-26.

- Qiu WY, Yao YF. Mycotic keratitis caused by concurrent infections of Exserohilum mcginnisii and Candida parapsilosis. BMC Ophthalmol 2013; 13: 37.

- Mukherjee PK, Chandra J, Yu C, Sun Y, Pearlman E, Ghannoum MA. Characterization of fusarium keratitis outbreak isolates: contribution of biofilms to antimicrobial resistance and pathogenesis Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2012; 53 : 4450-7.

- Choi KS, Yoon SC, Rim TH, Han SJ, Kim ED, Seo KY. Effect of voriconazole and ultraviolet-A combination therapy compared to voriconazole single treatment on Fusarium solani fungal keratitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2014; 30 : 381-6

- Das S, Konar J. Bacteriological profile of corneal ulcer with references to Antibiotic susceptibility in a tertiary care hospital in West Bengal. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 2013;11: 72 75.

- Yoon KC, Jeong IY, Im SK, Chae HJ, Yang SY. Therapeutic effect of intracameral amphotericin B injection in the treatment of fungal keratitis. Cornea. 2007; 26:814–18. [PubMed]

- Anane S, Ben Ayed N, Malek I, et al. Keratomycosis in the area of Tunis: epidemiological data, diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 2010; 68: 441–47. [PubMed]

- Anshu A, Parthasarathy A, Mehta JS, Htoon HM, Tan DT. Outcomes of therapeutic deep lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty for advanced infectious keratitis: a comparative study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:615–23. [PubMed]

© The Author(s) 2018. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.